CDE project 13 section 5: what can charities teach us about managing preferences?

- Written by

- The Commission on the Donor Experience

- Added

- April 25, 2017

What can charities teach us about managing preferences?

Charity case study 1: Botton Village and Camphill Village Trust

The history - how did Botton Village start fundraising?

Botton Village began fundraising in 1983. As a residential Camphill community in North Yorkshire, where adults with learning disabilities lived and worked alongside co-workers, together creating a vibrant community that benefitted all, they were short of money.

They needed funds to help to improve existing homes and workshops, and develop the village further. Income in the form of grants for those with learning disabilities, and some income from the village’s own products that they created and sold, was not enough.

They had a real need for extra money to fund investment – but they did not know where to turn.

It was this situation of need, and the chance attendance of co-worker Lawrence Stroud at a fundraising conference where he met Ken Burnett, that led to Botton’s fundraising programme being born – in a community with no fundraising knowledge, experience or culture, and no fundraising staff.

What drove Botton Village’s approach?

Starting from zero meant that Botton Village defined its own approach from the start. As a place where co- workers had chosen to go to live, to share their lives with adults with learning disabilities, everyone’s focus was very much on life within the village. People were nervous, and even suspicious of fundraising – contacting people they had never met, openly asking for money for a place those unknown people knew nothing about.

Against a background of bafflement, nervousness, and some outright hostility (as well as some hope!), the first cold direct mail appeal was developed. It was a surprising success.

It was also a learning experience – and became the first small step along a long journey of trial and discovery, as Botton Village gradually evolved its own unique approach to how to reach out to donors as friends, and how to raise money by bringing donors as close as possible to the real individuals (people portrayed as having their own special abilities, rather than disabilities) who they were supporting.

This reticence to fundraise, together with a view of ‘Why on earth would anyone support us?’ gave fundraising its own strong ethos from the very start.

What did this mean for fundraising?

No principles were written down, but if they had been, they might have been roughly as follows:

- If we’re going to ask people we don’t know to support us, we’ll ask them, very respectfully, to be friends of our community.

- If we’re going to fundraise for the people who live here, we need to share how this rich mix of people, each with their own special talents, qualities and abilities, achieve amazing things in their lives (despite how other parts of society might view or treat them). We’ll help them to speak for themselves, and tell these new friends why Botton Village matters to them.

- We will share our needs openly and honestly, and only ask for what we need. We will share the good news of what has been made possible with the help of these friends.

- We’ll respect these people who are becoming our friends. We won’t use jargon. We won’t be pushy. We won’t hassle them or use types of fundraising some say they don’t like. We will listen to what they say. We will try our best not to do anything to harm this amazing bond with kind friends most of whom we have never met.

- We will ask them to visit the Village if they would like to, and try to give them a good experience. We will encourage them to get in touch with us whenever they have a question.

- Each one of these friends matters. The lady who manages to give us £10 from her pension is just as important as the person who is more easily able to give a much larger gift.

- Some people don’t want to hear from us too much, or even at all – so we’ll be clear about the sort of communication we’d like to have with them. We will give them choices about what they would like to receive, and how often. They will always be free to change those choices. We’ll trust that if they want to stay with us, they will.

How was this approach implemented?

This approach led to a programme as follows:

A newsletter was developed: ‘Botton Village Life’ to introduce the people of the village and their lives, share the ethos behind the community, build a deeper understanding, and feedback on what was achieved. It was felt to be important that the newsletter did not ask for money.

Separate appeals were created around specific projects needing funds, and these were sent with the newsletters.

A warm, chatty letter spoke to donors as friends, sharing needs gently, and in a friendly way. The letter always came from the same person, so that the donor knew what to expect and got to know a particular representative of the community.

What did this mean for donor choice?

As the fundraising grew, a small office team developed to help create the fundraising communications, look after donors and bank their donations. A fundraising group was developed to lead the fundraising: made up of some co-workers, some of the small office team, and agency Burnett Associates (now Burnett Works).

Feedback from some donors led the group to realise that some people wanted less contact. Analysis of donors’ donation history showed that though donors received four or five appeals each year, some appeared to consciously decide to give just once each year. Some said they wanted information, but not actual appeals. Some did not want to hear from Botton Village again, perhaps having given just once for their own reasons.

So a page called ‘How Botton Village can help you’ developed. It was placed on the reverse of the reply form, and included in every mailing: as a place where Botton Village thought about what you, the donor, might like: how to make you feel as comfortable as possible, encourage you to get in touch by calling the office, offer you more different information or the chance to visit – or to express your communication preferences.

Each donor could choose:

- To receive information but no appeals for funds

- To receive all four regular communications per year

- To hear just once a year, at Christmas

- To move back from just once a year at Christmas to all four mailings

- Not to hear from Botton Village again

Was offering donors choice tested?

Botton Village offered its donors the chance to express their communication preferences from very early on.

It was not tested against a ‘control’ group who were not offered these choices – because for Botton, it was about respecting this remarkable group of unknown and generous friends, and treating them as the Botton team felt they themselves would wish to be treated. For them, this came above maximising short-term income for the village.

So, they developed this approach because they believed it was the right thing to do. This strong ethos came first and foremost – and perhaps not surprisingly, other unexpected benefits followed.

How donors felt about Botton Village

Over time, we became aware that:

- People enjoyed hearing from Botton Village. They read what they were sent, and listened

- People got pleasure from seeing the difference they were able to make

- Donors felt part of Botton, interested in people’s lives, looking forward to hearing news, many choosing to make the effort of a long trip to visit the village. As a new cause Botton had always invited donors to come visit, to see first hand what their support was achieving. Initially this was more in hope than anticipation but donors loved it and even those who couldn’t come felt happy to be invited. before long a villager was given a job - full-time - of looking after a steady flow of visitors, each of whom became a friend for life

- People trusted the charity People felt loyal and committed to Botton Village

- Many were prepared to stand up and take action if they felt Botton needed support

- Many continued to give for many years

- Some introduced their company, or trust; or offered to raise money for Botton through their own fundraising efforts; or offered gifts in kind – and continued to give in these different ways

- Many went on to leave a legacy.

How has this evolved and developed over time?

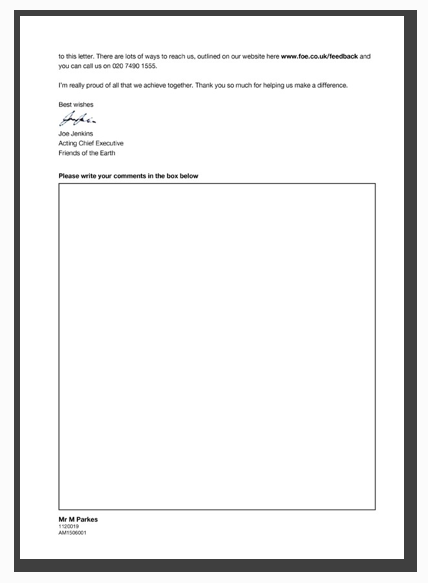

Over the years, through direct marketing campaigns, a large and loyal group of donors was recruited. Botton Village felt that after 18 years of fundraising it had largely met its immediate needs, and the programme began a careful plan of transition. Gradually supporters were introduced to other Camphill Village Trust (CVT) communities (‘Botton’s wider family’), in order to fundraise for the whole of CVT – then 11 different communities across the UK. The last mailing from Botton Village reached donors in June 2002 – and since then, The Camphill Family has been the fundraising vehicle for the whole of the Camphill Village Trust.

When Botton Village fundraising became The Camphill Family, almost all donors chose to make the step to support the new family of communities. Appeals shared, and continue to share the needs of one or more projects or communities at a time.

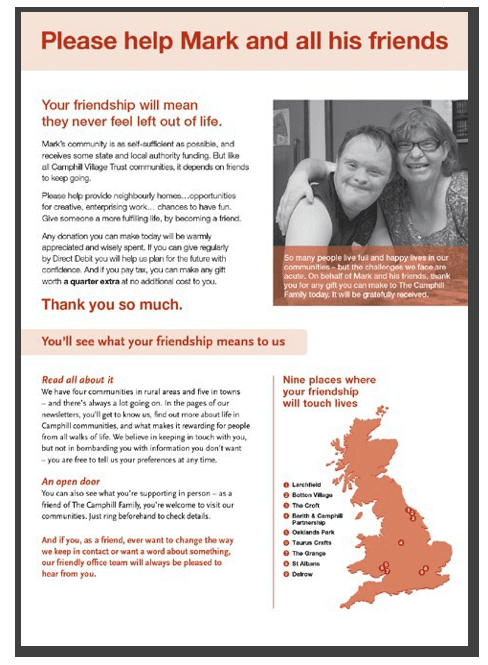

Making a promise at the very start

In all of its donor recruitment communications, CVT makes it clear that it is seeking friends. Friends who will be sent news and updates, invited closer if they choose, but friends who will be given control of what they receive, and whose wishes will always be respected.

Donors continue to be offered choices in every mailing from the charity:

CVT keeps in touch with donors primarily via four mailed communications per year, which enclose a newsletter, a leaflet showing a project in need of support, a letter, and reply form. On the reverse of the reply form, entitled ‘Let The Camphill Family help you’, donors continue to be offered a range of choices, as follows:

- To receive information only, but not appeals

- To receive all four regular communications per year

- To hear from CVT just once a year, at Christmas

- If they have chosen this option, to revert to receiving all four mailings

- To receive information and appeals by email

- Not to hear anything from CVT again

- Donors are also offered the chance to find out more, plan a visit, or get in touch with one of the office team with any query you may have.

What are the results?

CVT’s results are remarkable, and donors show great generosity and great loyalty.

- Of a current total of 58,000 donors - 30,744 (53 per cent) have chosen to hear just once at Christmas. Response rates in these Christmas segments reach up to 59 per cent, with an average gift of nearly £68 across the mailing. Response rates in these segments are considerably higher than in comparable segments of people happy to hear four times per year.

- 4,400 donors have chosen just to receive information only. They receive the newsletter and details of the current appeal, but no direct appeal for money is made, and no reply form is sent. Yet the two main segments of information donors still give at between 26 per cent and 39 per cent.

- Together these 58,000 donors give over £3 million pa.The average lifetime value (without legacies) of all donors still actively giving is £948. The average lifetime value of all lapsed donors is £215 per donor. The average donor gives for over 9 years but many give for much, much longer.

- In the last 4 years, legacies traceable to donors have ranged from £1.38 to £1.93 million per year - making up between 56 per cent and 83 per cent of all legacies received by the charity.

How do donors feel about being offered choices?

Recent qualitative telephone research confirmed how much supporters enjoy supporting the Camphill Village Trust. They commented on the quality of the information they received, and how it made them feel closer to the people they help to support.

They marked out CVT as a charity they trust not to take advantage of their goodwill – in sharp contrast to feeling utterly taken for granted by and fed up with the approach they feel they get from so many charities they support. Some comments follow:

‘With Camphill I never feel pestered. It feels utterly appropriate. They ask when the need arises. It’s important.’

Supporters are aware of the communications options given to them by CVT (to receive communications quarterly, or just once a year at Christmas, or to receive information but not appeals, or not to hear further at all). They appreciate the sense of control this gives them, even if they do not choose to exercise any of the choices.

‘I’ve noticed that I can tick a box about when I want to get the letters etc, but I don’t fill it in as I don’t need any changes. I’m happy to get it four times a year. I know I can tick it but I don’t want to. I do think it’s helpful to be given the choice.’

‘I like the fact that you asked me how I wanted to be contacted. I do one donation a year at Christmas. I was asked and you never contact me at any other time. You contact me at Christmas. I do my donation. I haven’t got time to read a whole load of stuff all the time and I don’t want to get things through the letterbox on a daily basis. Camphill did what I asked and I’m really impressed.’

‘I think it’s a good idea to get the options. I’ve just emptied out a drawer this week of letters from dozens of charities we’ve supported and you think, that’s a hell of a lot of money wasted on paper. You put the forms in the drawer and you feel guilty about not supporting them. But there’s only so many you can do.’

‘We’re down to once a year now for newsletters and we always give at Christmas. They asked me and that’s what I decided I’d do.’ ‘Camphill, after my request, only send me once a year, which is great for me. But Camphill is the odd one out of all the charities we support.’

‘I notice there’s something to tick, but I let them come every quarter.’

How does this contrast with what donors too often feel?

This appreciation is in marked contrast to donors’ treatment by many charities, which leaves people feel cynical, irritated, and taken for granted. We frequently heard words like annoyed, fed up, cross, guilty, pestered, pushy, aggressive… confirming the damage the sector overall has done to many precious relationships. Here are some of the things people said; notice how many of them voice a feeling of being out of control of how, how often, and with what the charity is choosing to contact them.

‘I do support other charities. I find others quite pushy. They cotton on to you that you’re prepared to give to charity and they don’t let go. They don’t give you the choice. You get things through your letterbox constantly.’

‘Giving doesn’t stop the begging letters coming in.’

‘There’s nothing more irritating than having endless requests for money every 2 – 3 weeks. We get quite cross about it.’ ‘You get on their mailing lists and that’s it. XXX are terrible… we get fed up…’ ‘Within months of setting up the direct debit, I had a very aggressive fundraising call. It was appalling. I didn’t stop the direct debit… but it wasn’t nice.’

‘You get people from call centres and it doesn’t matter what you say to them, they just ask the same list of questions…’ ‘The other thing I don’t like is when charities send you free gifts… it puts me off… they don’t ask me, they just come…’

‘Charity fundraising on the whole is all very soulless… everybody is fighting for the same bit of money…’

It’s not just about choice and control

Of course, the success of Botton Village, and the Camphill Village Trust’s fundraising programme is not just about the choices that the charity gives its supporters.

These are just one of the ways in which CVT expresses its respect for its donors:

CVT decided long ago not to use prompt levels on reply forms because some donors expressed a dislike of feeling they were being ‘told what to give’. The voice of a few was enough to cause the charity to believe that many would prefer to be left completely free to choose their amount. This may be controversial, but is a good

example of how respect for donors lies at the heart of CVT’s fundraising. Average gifts values remain high: in the past year they have varied between £50 and £68.

Though fundraising by telephone is understandably popular and, done well, can be used to enhance and develop relationships with donors, CVT decided not to use this channel of communication to fundraise, because they had reason to believe that some supporters would find this too intrusive.

While the opportunity to give regularly is always available, CVT has preferred not to directly ask donors to convert to a regular gift. Some donors had expressed a view that they enjoyed giving one-off gifts much more, making individual decisions to give amounts they choose, at times they choose and getting pleasure from each gift. Hearing that from some donors was enough to make the charity feel that donors should not be strongly led to a particular type of giving. Although just occasionally, for example on a major anniversary when looking ahead at longer-term challenges and needs, regular giving is suggested as a way the donor can help the charity to tackle these challenges longer-term. And regular donors continue to top up their giving: between 11 per cent and 18 per cent of committed givers (depending on segment) gave an extra gift on top of their committed gift last Christmas.

The tone and quality of communications aim to bring the donor closer to the people CVT supports, to show people succeeding in their lives, to share challenges, to show opportunities to achieve something tangible and to give feedback and show appreciation of the important part that friends play… these are all marks of a fundraising programme which sets out to build long-term, mutually rewarding friendships; to respect donors and not treat them in a way which may be unwanted or unwelcome.

CVT has stuck to its principles. It has a small, committed team of people involved in fundraising. This team has remarkable continuity, the know their donors well and are passionate about treating supporters well at every opportunity.

In the face of a challenging environment, the Camphill Village Trust has undergone changes over the past few years, and the process of evolution has not been easy. Throughout these changes, the fundraising team have been as committed to donors as ever.

Case study 2: Hosanna House and Children’s Pilgrimage Trust (HCPT)

Background

Hosanna House and Children’s Pilgrimage Trust (HCPT) is a 60-year old faith charity. Volunteers take disabled and disadvantaged children and adults for “pilgrimage” holidays in the south of France. The holidays are open to all, regardless of faith, and are life changing for many.

The charity’s Head of Fundraising, George Overton, says: ‘I learned about the Botton Village/Camphill Village Trust preferences slip some time ago. Ever since I’ve looked for an opportunity to try something similar.’ He felt that the Botton/CVT initiative is acclaimed but seemingly rarely imitated.

The sad death of Olive Cooke in May 2015, and the subsequent media criticism of fundraising, seemed an ideal opportunity to adapt the reply form options for HCPT. The media narrative seemed to be that charity donors wanted (at the very least) an easier way to opt out of, and more choice in, receiving communications. Charities seemed to be resistant to providing it.

HCPT was in an ideal position to oblige, George says, ‘Not only because I believe HCPT’s supporters are particularly dedicated to the cause. But also because I had no fear in sharing such plans with HCPT’s trustees.’

In July 2015 the trustees approved the project, agreeing that the fundraising climate was such that offering donors more choice was essential. This was despite the importance of not damaging the amount of fundraising income received from direct marketing.

How it worked

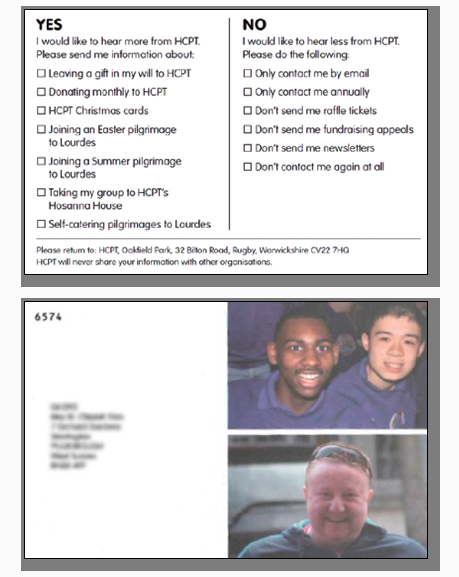

George continues: ‘Just like Botton/CVT, I didn’t want to offer donors merely negative choices - I wanted to offer positive choices too. An obvious way of doing this was to offer “Yes” and “No” tickboxes, the former offering to send donors more information, the latter to send less.’

A member of the fundraising team worked with a designer to produce a postcard sized preferences slip with Yes and No columns offering different options. Unnecessary text was kept to a minimum. The reverse of the slip had the donor’s contact details on (for ease of response tracking), plus imagery used elsewhere in the mailing. The postcard could be returned in the reply envelope enclosed.

HCPT also adapted its ThankQ fundraising database and mailing schedule to be able to handle the choices being offered, and prepared how to record the responses.

In August 2015 HCPT tested the slip in a split 50/50 raffle mailing to warm supporters. Half of the mailing list received the slip and half didn’t. After seeing positive results from the test, they had no worries about including the slip in all direct mail from then onwards, comprising a thrice yearly newsletter, twice yearly appeal, and annual raffle mailing.

Results (after over a year of including the slip in mailings)

The first time the slips were mailed, 3% of people returned them. But after over a year this settled down to 1% on average, of which:

• 39% opt out of hearing from HCPT again (0.04% of those mailed overall)

• The same amount again, 39%, want less contact, but still want to continue hearing from HCPT

• 5% want more contact

Of those wanting more contact, most want to receive the charity’s Christmas card brochure. A handful of people request information about leaving a gift in their will.

Supporters find the blank space on the slips useful to fill in their own messages to the charity. Over a quarter of respondents write something in the space.

Of particular note is the supporter who said “Thank you, these options are appreciated”. Also it was telling that another wrote “Please no raffle tickets! Today I received five charity appeals all with raffle tickets!” Imagine what receiving so much charity direct mail every day must feel like.

In the initial 50/50 test of the slips, HCPT found the slips had a negligible (quarter of a percent) impact on response rates overall to the mailing.

Conclusion

George Overton concludes the story: ‘Presumably charities don’t use such devices because they fear their mailing lists will be decimated. But HCPT’s experience is that this is unlikely to be the case – only 0.04% of those receiving the slip opt out. However HCPT’s experience is that it unquestionably improves the donor experience - how could it not? After all, shouldn’t all fundraising charities be offering preferences to their donors?

‘The old-style tick box or email address, offering an opt-out, mentioned in small print, isn’t enough anymore in the new fundraising climate we’re working in. Offering donors choice, and preferences, is vital.’

Case study 3: CLIC Sargent

In August 2015, in response to the prevailing climate of negative publicity surrounding charities, CLIC Sargent decide to move proactively to give donors more choice and control.

Up to that point, they had mainly reacted to what donors had asked in terms of choices. But increasingly they had realised that people wanted to engage in the ways that suited them best, in terms of type of communication, channels and devices.

This was seen by the charity as a positive way to be more proactive in giving people more choice and control, and better quality engagement with the charity, and the move was fully supported by senior management and trustees. Any concerns about short-term impact (people choosing not to receive appeals for example) was more than offset by a belief that greater donor satisfaction and loyalty would bring long-term benefit. There was an agreement that it was right to focus on donors’ experience, and so to put ‘quality’ over ‘quantity’: while the pool of donors each communication reaches might be slightly smaller, unwelcome communication is avoided and response rates and ROI should be improved.

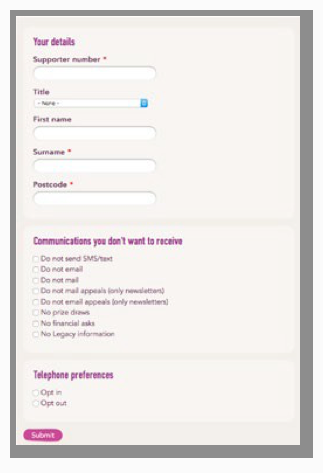

The options are offered on the website, via email, and on phone calls as well as on printed communications including administration letters. Once made they can easily be amended again on an ongoing basis. Since the majority of supporters receive emails, it has been easy to offer these choices to the whole database of 140,000 people.

The team download information from the website weekly and import this to the database, and use the Fast Stats tool, linked to their Care database, to analyse information and make selections. Once the information is recorded on the database, the data team look at how to best select for each communication, to make sure that what is received reflects the donor’s wishes.

Since August 2015, 244 supporters have chosen their communication preferences. People comment positively on being asked about what suits them, knowing they can make and amend choices if they wish to, and knowing that the charity is setting out to meet their needs.

CLIC Sargent is pleased to have taken this proactive move to offering more choice and meeting people’s preferences, believing that, first and foremost, this is very much the right thing to do; and that by doing so, other benefits of trust, loyalty and long-term value will follow.

Case study 4: offering choices through fundraising products

Some charities create fundraising ‘products’ that enable the donor to develop a more personal sense of connection with the cause they are supporting. At best, these may help the donor to reach into and draw upon their own experience or beliefs, and can foster an emotional connection which helps the donor to support in a way that becomes very personal, and therefore very precious. The choices a donor makes can contribute in important ways to this.

For an organisation such as PLAN International, an individual child is linked to an individual donor and becomes the representative of how a community is being helped. Letters lead to an exchange of details about each other’s lives, and a very real sense of what is being achieved. This personal and individual connection is supported by other information which reinforces how the charity is creating change across many communities and countries. These links can last for many years, with sponsors often going on to support a number of children in succession, creating valuable long-term relationships between the donor and the charity.

Developing and offering more tailored products can be another powerful way to offer choice, help people to express their preferences, and tailor feedback to them.

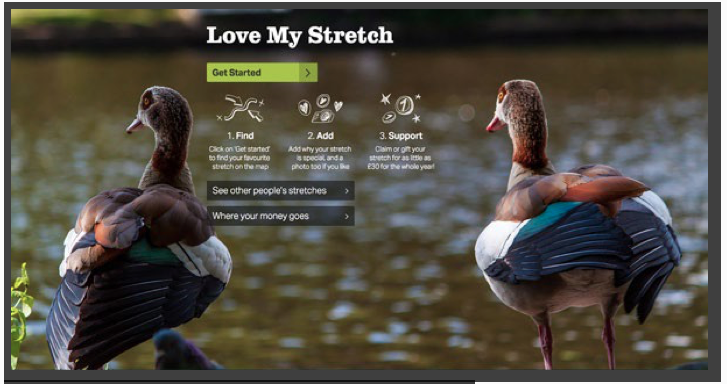

Canal and River Trust

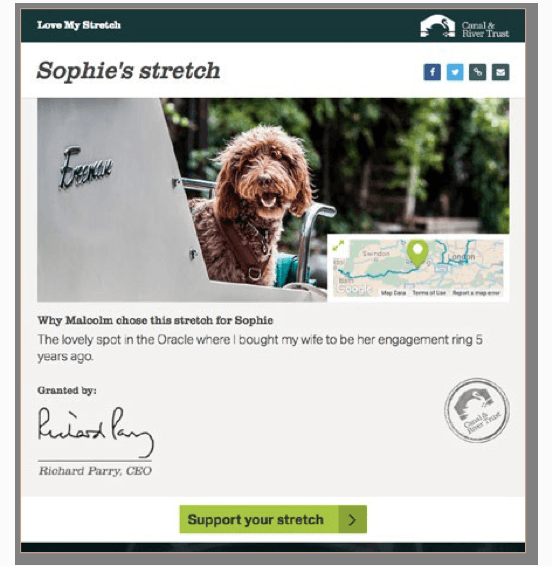

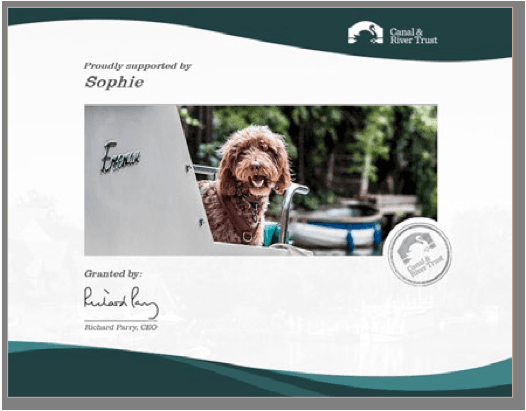

The Canal & River Trust offers supporters the chance to ‘Love My Stretch’. For a sponsorship amount of at least

£30, supporters can choose an area of canal or river to support for a year. Supporters can share an image and words on the charity’s website, allowing them to express what that particular place means to them… or give it as a gift to a friend or loved one with a connection to that bit of waterway. In doing so, you join a community of waterway lovers sharing their own personal images and words, creating a patchwork of people caring passionately about these beautiful places.

Talking to boaters, people out and about on the towpaths, at open days and museums, it became clear to the charity’s fundraising team that the waterways mean different things to different people. Before ‘Love My Stretch’, supporters could engage financially by becoming a ‘Friend’ or donating cash gifts to local appeals, but there was nothing that allowed them to express their passion for a particular stretch of waterway. ‘Love My Stretch’ was the solution: designed to be an audience-led, all-digital proposition that engages positively from the outset.

Since launch, the product has been embraced by people from all walks of life – from dog walkers, community groups, individuals celebrating the life of a loved one to romantic reminiscers – everyone has a story to tell about their favourite stretch, and this is precisely why the product was created – to give supporters of the Trust a vehicle to express this connection.

As Silvie Morelli, from the Canal & River Trust, says: ‘The big bonus for us is it gives insight into how people connect with us emotionally – this is important for any charity but especially us as a relatively new one, previously Public Sector and therefore often viewed as having a purely ‘maintenance’ function. ‘Love My Stretch’ is also a valuable resource we can mine for ideas and features with local resonance, to help feed into the bigger picture, allowing us to streamline and tailor our programme to further engage donors.’

She adds: ‘Regionalising content has had a powerful effect on our retention programme. In one area, email open rates increased by >5% in the next send and CTO by >50%! Unsubcribes are lowering with every regional send that goes out.’

Some favourite stories and reasons for support: “Where I fell in love with my wife for the first time.”

“On my first narrowboat trip nineteen years ago, I watched the sun rise from these locks, I was hooked on canals from that moment.”

“This is where our puppy Labrador, Murphy, fell in..... and learnt to swim.”

“Need to conserve Canal Street for the LGBT community, past, present and future.”

Since launch in late 2015, ‘Love My Stretch’ has generated close to 300 cash gifts for the Trust. However, this product is more than just income generation – it has highlighted an invaluable rich fabric of individuals keen to engage, support and learn more about the Trust’s work across their network of canals and rivers.

Supporters of ‘Love My Stretch’ will be taken on a bespoke onward email journey, with the aim of educating them about the Trust’s work, inspiring them and offering opportunities to support the Trust with a regular gift by becoming a ‘Friend’.

Here is a charity sharing the pleasure of a shared passion, and helping supporters to make choices and get involved in ways that make them feel connected and involved, as well as learning as they go. It is a good example of how you can build donor involvement, sharing, learning and personal experience into the very fabric of how you support a chosen cause.

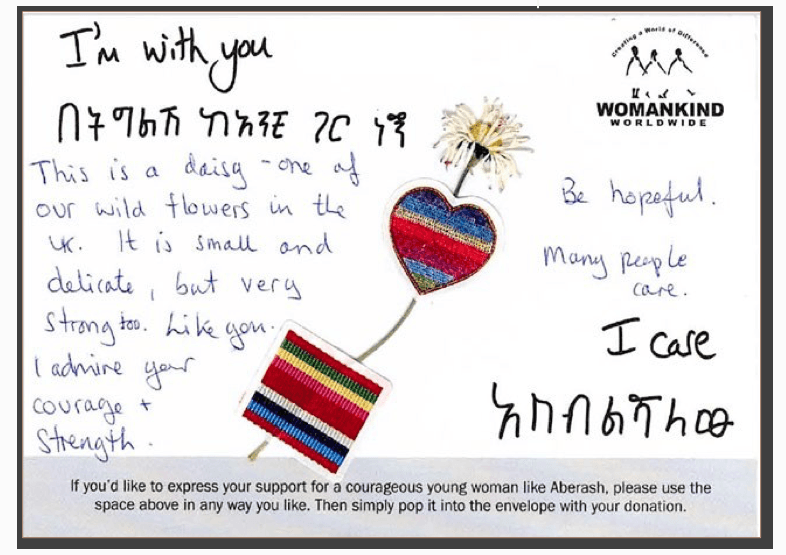

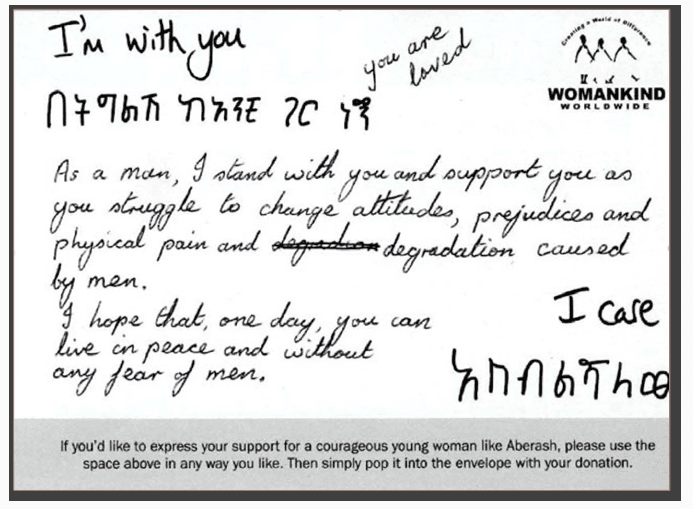

Womankind Worldwide

Other charities too give donors the chance to express their personal feelings – sometimes to a specific beneficiary. In a successful donor recruitment pack where Womankind shares the story of Aberash, a young girl who suffered FGM and a forced marriage, and who was helped out of her situation by the safety net of services provided by Womankind, donors are given the chance to send their own personal message of support to Aberash.

This is also expressing a choice – choosing to share sometimes personal thoughts and feelings – and by asking donors to express what they feel, people really think about Aberash has gone through, and form a much more personal and meaningful connection as they give their first gift.

In the thank you mailing, donors are invited to contact the charity if they would like different sorts or amounts of contact.

By dealing with people in such a personal way, the charity shows it supporters that they each matter individually to the charity and its important work.

Feed the Children

In just this way, at the height of the Bosnian crisis, emergency press ads were placed in newspapers by aid agency Feed the Children, alongside media headlines of the unfolding humanitarian crisis. Potential donors were given the chance to pay for a baby box of essential supplies to be provided to a mother and her family. As well as the tangible sense of giving one family in need a box of much-needed help, donors were invited also to send a personal message to be enclosed in the box of supplies they were enabling to be given. What a chance - to help one family, and express your support for them: enabling donors truly to give directly to a beneficiary in the midst of a terrible time. Once again, exercising this choice of including a message of support gave the donor a much more personal and meaningful engagement, and a rewarding sense of having made one family’s life a little bit better.

Case study 5: using the telephone to build relationships

With thanks to Jessica Bianchi-Borham, and Rebecca Patterson, of Pell and Bales

Some telephone calls (especially some of those made in the not so recent past) have been singled out by supporters as a particularly intrusive type of communication.

If it’s not done well, let’s look at how a fundraising telephone call can feel. You answer the phone, at a time not of your choosing. You are caught unawares, called away from something you were doing. The caller is prepared; you are not. There is nowhere to hide – it is a one to one conversation. Of course, you do feel sympathy and you’d like to help if you can. You may end up committing to something you’re being asked to do, that you didn’t really intend and may not suit you that well right now. You go away not quite sure you should have agreed to it and no closer to a cause you may or may not feel deeply about. Worse still, we know that some older people in particular, with little social contact, may be badly equipped to deal with a caller who is setting out with a particular goal in mind.

That’s a description of some of the calls that might have taken place in the past.

The opportunity now

Now let’s consider the opportunity. This opportunity, already happening in some quarters, is for something quite different. To use the telephone as a really positive channel that can enhance and develop the relationship between a charity and a donor, using the opportunity of a fluid one to one conversation to find out more, offer choices, gather preferences and help the donor to develop the relationship that suits him or her best.

Pell and Bales, who have now ceased trading, were looking at how telephone calls can be used in this way taking advantage of the unique one to one opportunity to chat openly and dig deeper: to discuss the charity and its work and find out about your connection; to find out what type of support or interaction with the charity might suit you best; to gather opt-ins for future calls; to listen to what the donor would like to say; to be led by the donor through the call, to find ways that the connection between donor and charity can become stronger and beneficial to both the donor and the charity.

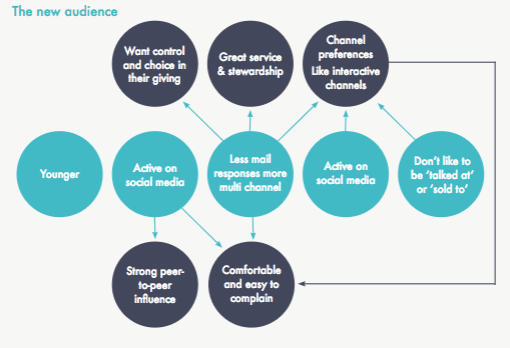

The new audience

Pell and Bales also note that the fundraising environment is changing as generational attitudes change. They identified a new, younger audience with quite different needs, expectations and influences.

At the same time:

- The internet has made it easier for your prospects to be reached by other charities: competition is greater

- It is easy to cancel a regular gift through online banking

- We are recruiting donors at levels (gift values) and on products they are not comfortable with, to sustain recruitment targets.

For these new donors, offering choice and control will be more important than ever – and charities will need to find ways to engage in dialogue that gives the chance to express their wishes and engage as they like.

A supporter-centric programme

Pell and Bales’ recommendations for a supporter-centric programme recognised that it is vital to look at the right measures of success: to realise that responsible, good fundraising cannot be measured by (short term) income alone.

- To truly understand how successful fundraising is, we must understand how it makes supporters feel

- By monitoring supporters’ feedback, including trends, we can better evaluate the fundraising that we do and make informed decisions about strategies moving forward

- Supporter satisfaction should become a standard KPI in all fundraising

- Health check scoring can be developed to evaluate this (and they were proposing ways to do this).

The right measures of success

A longer-term view on performance should be taken to ensure we are nurturing and protecting the relationship with the donor and not just managing a transaction. In addition to enhanced data capture and satisfaction surveys, Pell and Bales suggested that the following work could be done, using the phone, to enhance fundraising:

- Regular attrition reporting by campaign, audience and approach

- Complaint level and type reporting by campaign and approach

- Secondary campaign objectives should be developed to drive engagement and commitment, e.g. encouraging greater interaction through petitions or social media, building trust

- Regular satisfaction and feedback surveys should be done, including possible (tele)focus groups

- LTV models and forecasting should be built around a richer mix of supporter-centric KPIs

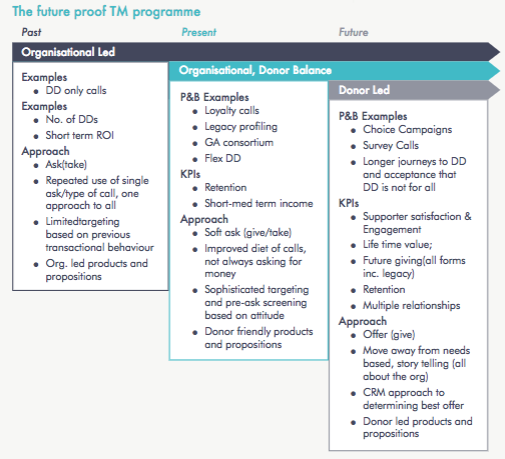

A future-proof telemarketing programme

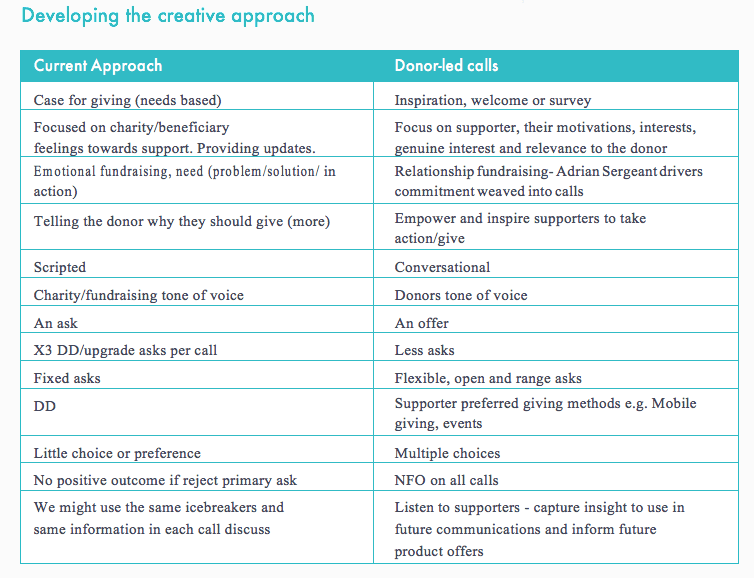

Pell and Bales mapped out a possible journey from the past, organisation-led approach; through the present, which balances the needs of the organisation with those of the donor, to a future, more donor-led approach; and looked at the creative approach behind a more donor-led call.

A supporter-centric programme

They identified that:

- Compared to the commercial sector, some of whom use the telephone in a much more creative, open and flexible way, the majority of calls made by the charity sector adopt a similar approach: problem, solution action and focus on the needs of the organisation and that

- supporters do not feel listened tosupporters pre-empt the reason for the call and are waiting for the ask

- little emphasis is placed on listening to the supporter, and allowing them to talk about their reasons for support

- The way the call is positioned can be developed differently – not just calling about the charity’s urgent need now

- Instead, focusing on the supporter, offering donor choice; making softer asks; finding out what really motivates the supporter; and if appropriate offering other non financial ways to help that might suit the supporter better.

Barriers to using the phone to offer real choice to donors

However, they also noted that we operate in a climate of tight budgets, with organisations that are increasingly risk-averse, tied to meeting one year targets, and where real change is hard to drive. They identified the barriers to using the phone to offer real choice to donors as being:

- Charity budgets mainly focus on year one income and ROI

- Lack of appropriate KPIs and reporting mechanisms around satisfaction, engagement and LTV

- Lack of senior management buy-in or engagement

- Slow decision-making within organisations meaning conditions for innovation are not present

- Risk-averse culture particularly following the last 12 months.

They are right.

Just as in other channels, we need to move from mass campaigns driven by one year ROI measures to more open, flexible, two way relationships where donors are consulted, listened to and offered the type of interaction that suit them – giving them choice and control, a chance to express what they prefer, offering reassurance, building trust, and leading to a more enjoyable, engaged, rewarding and valuable long-term relationship.

Case study 6: Friends of the Earth

Hand in hand with offering choices and managing donors’ preferences goes listening to what your donors think and feel about your charity.

In the wake of the many stories of bad practice from charities hitting the media in summer 2015, Friends of the Earth decided to broach the issue head-on with their supporters.

A letter went out from Joe Jenkins, Acting Chief Executive, to every single Friends of the Earth supporter. It set out clearly how much supporters are valued as the partners without whom none of the charity’s vital work could happen; showed appreciation and gratitude for all that they help to achieve; laid out the shared values that bring supporters together with the charity; acknowledged the situation in the press; and asked whether the supporter was happy with the ways that charity communicates with them.

It explained how it communicates with donors, and why; what it hopes to achieve and give you; and what pitfalls it hopes to avoid. It openly asks donors to share their views, providing a space for donors to write back, and inviting feedback at any time.

What is so valuable here is a simple, honest letter to supporters; sent out quickly in response to a growing series of very public charity fundraising horror stories; asking supporters openly what they think. Such open dialogue,

inviting feedback and comment, reassures the supporter, gives them a chance to have a voice, and shows them that what they say will help inform how the charity will communicate with them in future.

It is such a simple step – but it shows concern, offers reassurance, invites your feedback about what works for you, and helps build trust and loyalty. You may not choose to reply, but you will remember being invited to have your say.