Harvard University: how Harvard got its name. Major gift fundraising in the seventeenth century.

- Exhibited by

- Frank C. Dickerson

- Added

- May 12, 2012

- Medium of Communication

- Direct mail

- Target Audience

- Major gift

- Type of Charity

- Education

- Country of Origin

- USA

- Date of first appearance

- September, 1633

SOFII’s view

This exhibit showcases two examples of major gift fundraising in the seventeenth century. Though centuries have passed, we think that the mistakes John Eliot made are still being repeated today. As this exhibit shows, the key to major gift fundraising in the 1600s was taking time to build lasting relationships and a shared vision – just as it is today.

Name of exhibitor

Frank C. Dickerson

Summary / objectives

In the seventeenth century, a large sum of money was required to support the building of a new school in Newtowne (which would later become Cambridge), Massachusetts. This exhibit compares the unsuccessful attempt by John Eliot in 1633 to raise the necessary funds with Nathanial Eaton's more successful method of major gift fundraising a few years later.

Background

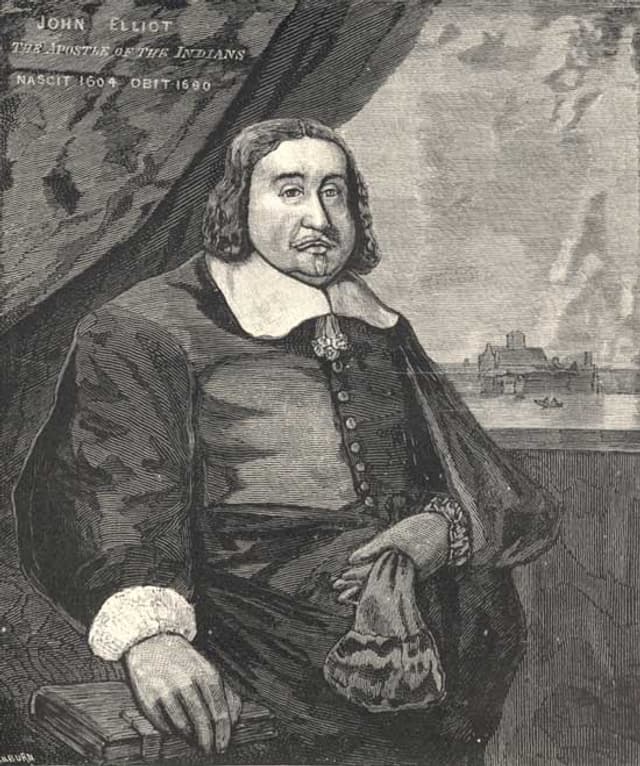

In September 1633, John Eliot, a 1622 graduate of Jesus College of Cambridge, wrote to a wealthy Suffolk gentleman, Sir Simonds D'Ewes, who he had met during his time at Jesus college. Eliot requested financial assistance from Simonds to 'erect a schoole of larning'.

We have included a portion of Eliot's letter here. In addition to the many obsolete spellings and seemingly odd abbreviations, as was customary at the time, the text uses the letter 'v' to represent the letter 'u' and the notation '&c' for the modern equivalent of 'etc'.

… if we norish not Larning both church & common wealth will sinke: & because I am vpon this poynt I beseech you let me be bould to make one motion, for the furtheranc of Larning among vs: God hath bestowed vpon you a bounty full blessing; now if you should please, to imploy but one mite, of that greate welth which God hath given, to erect a schoole of larning, a colledg among vs; you should doe a most glorious work, acceptable to God & man; & the commemoration of the first founder of the means of Larning, would be a perpetuating of your name & honour among vs: …. Such yong men as may be trained vp [m]ust beare theire own charges: only we want a house convenient, now the bare building of a house big enough for our young beginnings will be done with litle charge: I doubt not but if you should sett apart but 500 pound for that work, it would be a sufficient begining, & would make convenient housing for this many years; nay 400 or 300 would doe pretty well ….doe only this; send a sure bill of payment, of such a summe of mony to be imployed for such & such buildings &c: I say send such a bill to our worthy governour, & who else you will; & they will doe the worke presently, &, take payment in England, by returning that bill, & assigning it to be paide, as they thinke fitt for thire vse; or if you shall please send so much ready mony; or so much in marchandable commoditys; though it be troublesome...

Special characteristics

Eliot's unsophisticated and clumsy letter uses unsubtle flattery in an attempt to persuade the author to part with a significant sum of money, claiming that he will have done 'most glorious work, acceptable to God and man'. Eliot also focuses on a simple legacy motivation, suggesting that D'Ewes gift would result in naming the school after him and thus the 'perpetuating of your name & honour among vs'.

Influence / impact

Unfortunately for Eliot, his artless appeal did not work. The relationship between the two men was apparently not close and the letter did not apparently give a sufficient motive to Sir Simonds to part with his wealth.

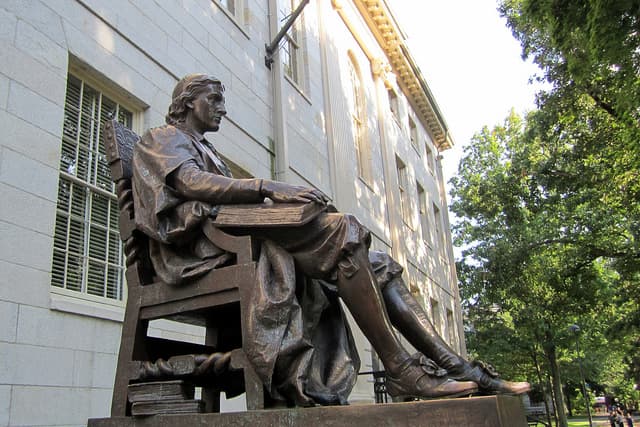

A more successful attempt took place a few years later in 1637. The transformational bequest left by John Harvard was the result of a close long-term relationship with the school's first master, Nathanial Eaton. Both men had attended Trinity College in Cambridge during their youth. When John Harvard arrived in Boston in May 1637, he became fully acquainted with Nathanial's work at the school and his vision for higher education in the new world.

John Harvard was so inspired and convinced by his friend's vision that when he died from tuberculosis in 1638, he bequeathed £799, half of his estate and his library of approximately 400 books to the school, which was eventually renamed the Harvard College in 1639.

The close relationship between Nathanial and John undoubtedly played a vital role in securing this legacy gift. By involving his friend in his work and sharing his vision for the school, Nathanial inspired John and obviously moved him to support the cause. With such interpersonal involvement and friendship, it must have been a simple decision for John Harvard to leave such a transformational gift.

Merits

Though the fundraising examples in this exhibit are almost 400 years old, we feel that there are still lessons to be learnt for the modern fundraiser. This exhibit reveals how fundraising communication often either focuses on personal involvement and people or on facts and concepts. As this exhibit proves, the former builds relationships and a shared vision and the latter does not. Building friendship and shared aspirations with your potential donor has always been and always will be essential ingredients in major gift fundraising.

While we know that you can't befriend every donor, we think that at the very least, this exhibit should provoke you into examining your communications with your major donors in a new light. Using informed language, it is possible to build in personal involvement, communicate drama and build a sense of friendship with even the most distant donor.

Other relevant information

This article has been adapted for SOFII from an article from Frank C. Dickerson.

Dr. Dickerson's research on the discourse of fund raising can be accessed at www.TheWrittenVoice.org.

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image