Magic moments part two: how some of the world’s best causes got started

By Aline Reed and Ken Burnett.

- Written by

- Aline Reed & Ken Burnett

- Added

- February 01, 2014

‘You never know when you’re going to come across a founding story’, says Aline. ‘Sometimes they seem to find you. A while ago, I was taking a walk with my sister-in-law when she pointed at a building and said ‘That’s where the RSPB was started’. ‘Really?’ I thought, ‘The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds was founded in a park in Manchester? That sounds unlikely…’

RSPB – a stroll through Fletcher Moss Park, Manchester

In the 1880s, feathers were the fashion. Victorian women’s hats were regularly decorated with feathers – some displayed an entire stuffed bird. Few of the wearers paused to think about where the feathers came from. Naturalist and philanthropist, Emily Williamson was an exception.

She was concerned about the cruel conditions suffered by birds bred for their feathers. She wanted to protect bird populations and she decided to make a stand.

From her home in The Croft, Didsbury, Emily set up The Plumage League. She invited women to sign a pledge not to wear feathers (except ostrich, which could apparently be plucked without harm to the bird).

Emily’s organisation later joined forces with the Fur and Feather League in Croydon and the Society for the Protection of Birds was born (the ‘Royal’ was awarded in 1904).

Today, the Croft is a picturesque red brick house surrounded by a park. A robin was singing in the walled garden when I walked by. He or she was probably celebrating not being a hat.

Centrepoint – from humble beginnings…

The Reverend Kenneth Leech had the grand total of £30 in the bank when he made the decision to set up Centrepoint, a charity for young homeless people.

Leech was the curate of St Anne’s church in Soho. One night in 1968 he witnessed a police raid on a club to pick up drug-addicted teenagers. Leech fell into conversation with Elizabeth Reid, a police inspector, and they discussed the need for a safe place for young homeless people to go late at night.

Leech had just £30 to his name, but from these humble beginnings the charity was born. They began opening up a basement in Soho to young people and, during the first few weeks, the numbers attending rapidly grew.

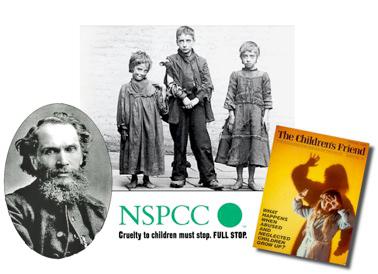

The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.

In the late nineteenth century many children in Britain suffered social deprivation and great hardship. The Reverend George Staite summed up society’s callous indifference to the plight of many of its youngest and most vulnerable in a letter to The Liverpool Mercury in 1881.

‘…whilst we have a Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals,’ he wrote, ‘can we not do something to prevent cruelty to children?’

At the time the answer was, apparently, no. Even the famous reformer Lord Shaftesbury said to Staite, ‘The evils you state are enormous and indisputable but they are of so private, internal and domestic a nature as to be beyond the reach of legislation.’

But the times were changing and despite such attitudes in 1884 the NSPCC did get started, even though for their very first case they had to bring the child involved before the court wrapped in a horse blanket, because in Britain at the time there were laws against cruelty to animals but not against cruelty to children. The Liverpool Society for the prevention of Cruelty to Children was set up by banker Thomas Agnew in 1883, a year before the official founding of NSPCC.

Little more than 60 years later the young Princess Elizabeth, newly appointed as president of the NSPCC, was able to say ‘I do not think there is any organisation which performs a more vital service to our country’s welfare.’

By 1900 the NSPCC had been granted a Royal Charter and had 163 inspectors. In 1904 the Prevention of Cruelty Act gave NSPCC its unique ‘authorised person’ status, which enabled inspectors to remove children from their home if they could convince a Justice of the Peace that there was serious risk of abuse or neglect. By 1905 the NSPCC had helped more than one million children.

Benjamin Waugh is widely credited as founder of the NSPCC though, rather like Cecil Jackson Cole and Oxfam, he was one of several, if perhaps the one who most made it happen. When he died the message inscribed upon his headstone was The Children’s Friend (see here).

The first Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act was passed in 1889. This was largely the result of five years’ vigorous lobbying by Waugh and his supporters. The NSPCC continues to uphold and develop the campaigning tradition established by its founder, acting as an independent voice for children and young people and a tireless campaigner for the idea that cruelty to children must stop. Full stop.

Freedom from torture (formerly the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture) – two founding stories…

‘I suppose the one thing that I am really proud of is the fact that, when I was in Belsen, the one lesson I learned was to bear witness, never to pass by. It is easy to be a bystander and I vowed never to be one.’—Helen Bamber

Helen Bamber 19 years old when she packed her bags and travelled across war-torn Europe to Belsen.

She arrived a few months after the liberation when the camp was overrun by typhus – the human suffering was overwhelming.

‘They would rock back and forth and I would say to them – I will tell your story. Your story will not die. It took me a long time to realise that that was all I could do – I couldn't solve anything. But I could listen.’

Helen Bamber has certainly lived out her promise never to be a bystander. As well as helping to establish Amnesty International, Helen Bamber founded The Medical Foundation for the Care of the Victims of Torture (now known as Freedom from Torture) in 1985.

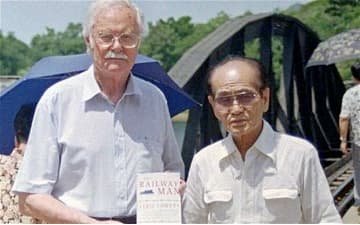

‘Probably the only organisation in the world whose staff and consultants are expert in the problems of the tortured’.—Eric Lomax, author of The Railway Man.

Lomax, who died aged 93 in 2012, was tortured by the Japanese while being held as a prisoner of war. ‘There is no cure for torture,’ he said. But with the support of The Medical Foundation for the Care of the Victims of Torture, Lomax, late in life, embarked upon a remarkable journey of reconciliation with one of his torturers.

Lomax writes very movingly about the support he received in the charity’s early years.

‘I had read an article about the launching of a new organisation. It was called The Medical Foundation for the Care of the Victims of Torture… Early in August 1987, I was invited to visit them. Helen Bamber received me personally.

‘I can still see myself sitting at the end of her desk with my back to the wall, haltingly describing why I had come in precise sentences that hinted at things I could not say. I still thought that what I was telling her was unique to me, and perhaps I felt a little ashamed of my difficulties; but when she told me that everything I had told her was so familiar to her, from countless victims of torture from many different countries, the most intense feeling of relief flooded through me…

‘…That meeting was like walking through a door into an unexplored world, a world of caring and special understanding…

‘…I received an invitation from Helen Bamber to become the first ex-serviceman from the Second World War to be accept as a patient of the Foundation. This changed my life, at nearly 70 years old.”

The Railway Man is an amazing book – its final unforgettable words are ‘sometime the hating has to stop’.

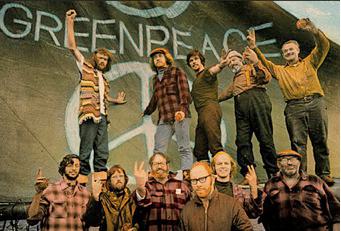

Greenpeace

In the late 1960s, the United States government planned to test an underground nuclear weapon on the tectonically unstable island of Amchitka in Alaska. Because of the earthquake in Alaska in 1964, the plans raised concerns that the test might trigger earthquakes and cause a tsunami. A demonstration in 1969 blocked a major US/Canadian border crossing in British Columbia, with 7,000 people carrying signs that said ‘Don’t Make A Wave. It’s Your Fault If Our Fault Goes’. The protests did not stop the US from detonating their bomb.

No earthquake or tsunami followed the test, yet the opposition grew when the US announced it was to detonate a bomb five times more powerful than the first one. Among the opposition were Irving and Dorothy Stowe and Jim and Marie Bohlen, members of the Sierra Club of Canada who were frustrated by the lack of action by that organisation. They introduced a form of passive resistance, ‘bearing witness’, where objectionable activity is protested simply by mere presence.

Marie Bohlen came up with the idea to sail to Amchitka. The idea ended up in the press and was linked to the Sierra Club, which the Sierra Club didn’t like at all, so in 1970 the Don’t Make a Wave Committee was established for the protest. Early meetings were held in the home of journalist Robert Hunter and his wife, Bobbi. Subsequently the Stowe’s home became the HQ. In his 1969 chronology, Greenpeace, Rex Weyler says that the Stowe’s ‘quiet home’ became ‘a hub of monumental, global significance’. Some of the first Greenpeace meetings were held there. The first formal office was opened in a backroom in Vancouver.

On 16 October 1970 at the Pacific Coliseum in Vancouver Irving Stowe produced Amchitka, a benefit concert starring Joan Baez to raise money for the first Greenpeace campaign. The Don’t Make a Wave Committee then chartered a ship, the Phyllis Cormack owned and sailed by John Cormack. The ship was renamed Greenpeace for the protest after a term coined by activist Bill Darnell.

In late 1971 the ship sailed towards Amchitka and faced the US Coast Guard ship Confidence, which forced the activists to turn back. Because of this and the increasingly bad weather the crew decided to return to Canada only to find that news of their journey and reported support from the crew of the Confidence had generated sympathy for their protest. After this Greenpeace tried to navigate to the test site with other vessels, until the US detonated the bomb. The nuclear test was criticised and the US decided not to continue with their test plans at Amchitka. Greenpeace had its first victory.

Naming Greenpeace

Though the Don’t Make a Wave Committee was formed in 1969 Greenpeace refers to the protest voyage of 1971 as ‘the beginning’, but the exact origins seem to be disputed. The name of the Don’t Make a Wave Committee was officially changed to Greenpeace Foundation in 1972. There are differing views on who can accurately be called the founders of Greenpeace.

The environmental historian Frank Zelko commented that ‘unlike Friends of the Earth, for example, which sprung fully formed from the forehead of David Brower, Greenpeace developed in a more evolutionary manner. There was no single founder’. Greenpeace itself says on its web page that ‘there’s a joke that in any bar in Vancouver, Canada, you can sit down next to someone who claims to have founded Greenpeace. Co-founder Patrick Moore said, ‘the truth is that Greenpeace was always a work in progress, not something definitively founded like a country or a company.’

Founding moments are not always magic. At least, not all the time.

After the bomb

After the US nuclear tests at Amchitka Greenpeace moved its focus to the French atmospheric nuclear weapons testing at the Moruroa Atoll in French Polynesia. In 1972 the yacht Vega, owned by a former businessman living in New Zealand, David McTaggart, was renamed Greenpeace III and, sponsored and organised by the New Zealand branch of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, sailed into the exclusion zone at Moruroa to attempt to disrupt French nuclear testing. The French Navy tried to stop this protest in several ways including assaulting McTaggart, who supposedly was beaten so badly that he lost sight in one eye. Fortunately one of McTaggart’s crew photographed the incident. After the assault was publicised, France announced it would stop the atmospheric nuclear tests. But disputes over French nuclear testing in the Pacific continued. In 1985, in Auckland harbour, the French secret service blew up the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior, killing Fernando Pereira, a photographer. Greenpeace was never able to shake off its image with French public opinion that it was anti-French. A decade later French people still believed that Greenpeace saboteurs had sunk a ship of the French Navy.

In the mid-1970s some Greenpeace members started an independent campaign, against commercial whaling. The Phyllis Cormack again left from Vancouver, this time to face Soviet whalers on the coast of California. Greenpeace activists disrupted the whaling by going between the harpoons and the whales and the footage of the protests spread around the world. An iconic fundraising image was born.

Later in the 1970s Greenpeace widened its focus to include toxic waste, commercial seal hunting, genetically modified crops, climate change and protecting the Arctic and Antarctic wildernesses. Greenpeace remains what it has been from the start, the world’s most visible and most audacious environmental campaigning organisation.

Fred Hollows Foundation – A Kiwi who became an Aussie hero

‘I hope that on balance, I’ve given more than I’ve taken.’

This is how eye surgeon, Fred Hollows, summed up his life, but it’s something of an understatement. During his lifetime, Fred personally restored the sight of thousands of people. More important still, he set up clinics to help those who were needlessly blind and the Fred Hollows Foundation – set up shortly before his death – continues his inspirational work.

Fred Hollows was born in New Zealand but became an Australian. In 1990, Fred’s charity work led to his being voted one of the greatest living Australians. He is remembered on a version of the $1 coin.

Fred had intended to study divinity and devote his life to the church. There was a problem though. At college, ‘the piety of some of the other students really pissed me off.’ (Fred wasn’t a man to mince his words).

After a summer working in a mental hospital, he changed his plans.

‘Sex, alcohol and secular goodness are pretty keen instruments, and they surgically removed my Christianity, leaving no scars.’—Fred Hollows

Fred became a skilled eye surgeon and moved to Australia, where he discovered the scandalous chasm between the eye health of indigenous and non-indigenous Australians. Nearly half of Australia’s indigenous people had trachoma and the healthcare available to them was completely inadequate.

Fred worked tirelessly to restore sight to indigenous Australians, then expanded his work overseas to Asia and Africa. With the methods he pioneered, Fred could carry out a cataract operation for $25.

A year before he died, Fred Hollows made a promise to over 300 Vietnamese surgeons – to train them in the skills they needed to restore sight to hundreds of thousands of people.

‘All you blokes need is a bit of training and some equipment and you’ll be able to do it.’—Fred Hollows

Fred dedicated the final months of his life to teaching. He even checked himself out of hospital to travel back to Vietnam and keep his promise.

Fred was also a good fundraiser. Determined to make people understand the effects of a cataract, he created a cardboard and plastic mask to simulate the effect. When invited to speak to business people, fellow medical professionals, politicians and donors, Fred would make them all put on a mask.

‘The effect of putting on the mask is no laughing matter. You are plunged into the world of the blind, where only light and dark and vague forms are discernible – no distinct shapes or features.’—Fred Hollows

Thanks to Fred, people understood that ‘cataract blindness is severe, traumatic and yet curable.’

Through the Fred Hollows Foundation, Fred’s work to end avoidable blindness continues. The charity works in over 40 countries around the world and supports indigenous communities in remote parts of Australia.

University College London – selling shares to raise money for a new university

How do you raise money for a university? In 1826, Thomas Campbell and Henry Brougham set themselves the challenge of raising £150,000 to n£300,000 to establish London’s first university. At the time the only universities in England were Oxford and Cambridge.

Campbell and Brougham wanted their university to be different. In a radical break with tradition, UCL was to be set up free from the influence of the Church. Students were welcome regardless of their race or religion.

To raise funds, Campbell and Brougham sold shares for £100 to people who believed in this new approach to higher education. Amongst them was philosopher and jurist Jeremy Bentham.

Bentham was the proud owner of UCL share number 633, but also inspired UCL’s tradition of radical thinking.

Bentham is frequently believed to be the founder of UCL. This is because his auto-icon (or dressed skeleton) sits in the South Cloister.

Bentham believed that the dead should be useful to the living and we took him at his word when we recently brought him back to life to raise money for UCL. (To see how a founding moment can become a successful fundraising campaign, click here).