Deerfield Academy: Bruce Barton’s fundraising letters from 1951, letter 15

- Exhibited by

- SOFII

- Added

- June 20, 2011

- Medium of Communication

- Direct mail.

- Target Audience

- Individuals.

- Type of Charity

- Children, youth and family.

- Country of Origin

- USA.

- Date of first appearance

- 1951.

SOFII’s view

This is a highly instructive example of great feedback and accountability. It's an end-of-the-year letter, a summary of how well we – the donor and the school, the reader and the writer – have done in our fundraising over the past 12 months. But it's also an inspirational example of maintaining engagement and momentum in the middle of a long, protracted campaign. As usual with Bruce Barton the letter is superbly written, relaxed, easy and disarmingly captivating. As an earlier commentator on SOFII said, 'You feel as if the letter is written just for you.'

Nowadays we might call this a donor care letter, or describe its sending as donor relationship development. In reality, its role is retention, even upgrading. So here is a 60-year old example of the very skills we so urgently need to develop today, if our fundraising is to succeed, long term.

Creator / originator

Bruce Barton.

Summary / objectives

In any long capital campaign – and this one stretched over more than five years – the challenge is to keep alive the flickering flames of each donor's interest and involvement, to stoke it to just the right level so that they will stay involved and keep on giving. So this letter is more about feedback than solicitation. But Bruce Barton was instinctively aware that these two are either side of a single coin; both are complimentary, essential parts of effective fundraising. It's a lesson today's fundraisers would be well advised to take to heart.

Background

As an example of how to show donors your prudent control of fundraising costs read Barton's description on page one of how he managed to reduce the photographer's bill for taking the fine photographs that accompanied this letter (sadly these images are now lost to us, but hopefully some kind SOFII reader will shed light on their whereabouts and we'll be able to add them later for your edification).

But we don't need those photos, really, to imagine in our mind's eye the achievements of those skilled workers in and around Deerfield who are so proud of their work and productive in their outputs when they create 'such beauty and quality as tells its own story and produces savings of hundreds of thousands of dollars in money'. Barton blends news with nostalgia and good husbandry to weave an irresistible tale of safe stewardship and sound progress that would gladden any donor's heart.

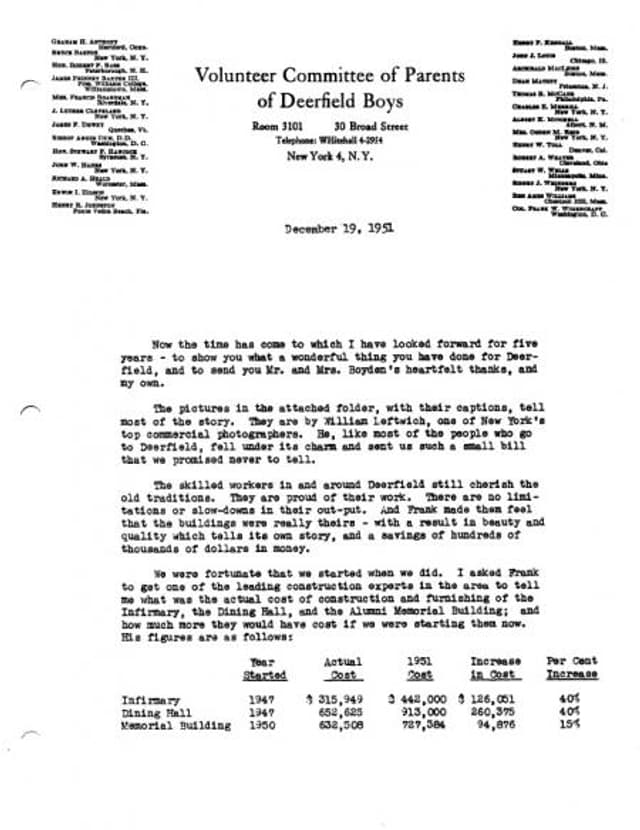

The results table on page one is particularly noteworthy.

In the pretext of relating the history of the fundraising committee's first meeting he introduces some shameless moral blackmail for those parents who as yet haven't 'given till it hurts'. Barton does lay it on a bit thick at times, such as when he tells of the headmaster going to bed every night for years worried about an epidemic, or the school hall bursting into flames. But it's all good stuff and great fundraising. He then calmly relates how they've already raised a total of $2,625,000 – a grand achievement by any standards.

Barton then goes on to name (presumably with their permission) the previously mysterious major donors whose lead gift had fuelled the campaign. It's a fine example of the power of earmarking and matching gifts rolled into one letter. Then, in the equivalent of a masterly PS, on page three Barton slips in a disguised further ask among the congratulations and actually gives donors 'permission' to respond to it.

Fine fundraising writing indeed.

Other relevant information

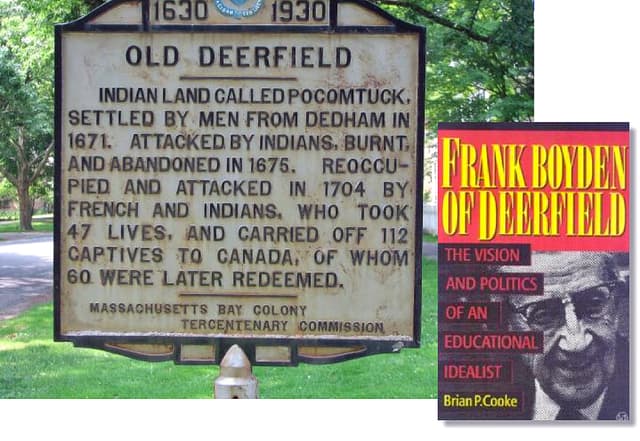

'When Frank Boyden, who was soon to become the new headmaster of Deerfield Academy, arrived at Deerfield station he was only twenty-two. He walked downhill into the town for the first time, and he nodded, as he moved along, to women in full-length skirts, girls in petticoats, and little boys wearing long-sleeved shirts and bowler hats. Deerfield, Massachusetts, was essentially one street—a mile from the north to the south end—under shade so deep that even in the middle of the day the braided tracery of wagon ruts became lost in shadow a hundred yards from an observer. Twenty years would pass before the street would be paved, six years before it would be strung overhead with electric wires. Houses that had been built two hundred years earlier were the homes of farmers. Some of them tilted a little, and shingles were flaking off their roofs. Though the town was reasonably prosperous, much of it seemed slightly out of plumb. Deerfield Academy, the community's public school, was a dispiriting red brick building that appeared to have been designed to exclude as much sunlight as possible. A century earlier, there had been more than a hundred students in the academy, but now only fourteen boys and girls were enrolled for the approaching year, two of whom would constitute the senior class.'

Taken from Frank Boyden of Deerfield, by Brian P Cooke, Derrydale Press, USA, 2000.

Also in Categories

-