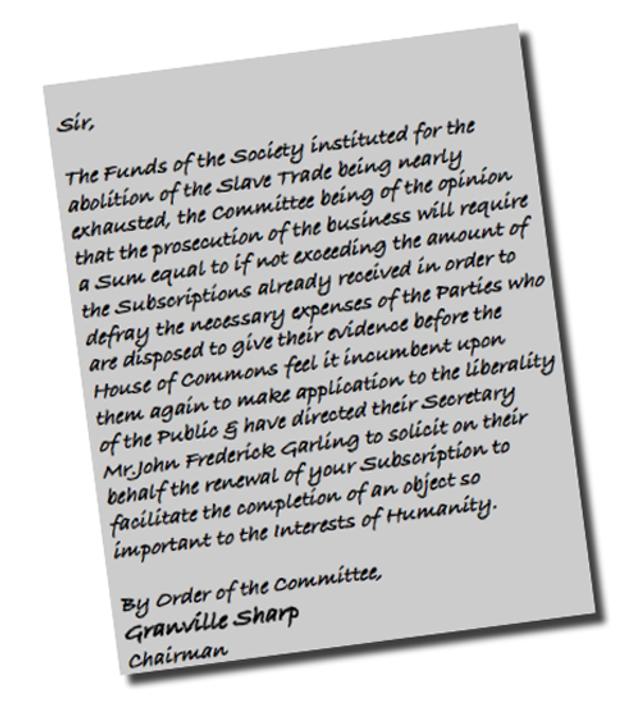

The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade: minute regarding the need for fundraising from 1788

- Exhibited by

- Mal Warwick

- Added

- September 11, 2009

- Medium of Communication

- Direct mail.

- Target Audience

- Individuals, intermediaries.

- Type of Charity

- Human rights & civil liberties.

- Country of Origin

- UK.

- Date of first appearance

- October, 1788.

SOFII’s view

The official record from the minute book of The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1788 offers a unique insight into how, more than 220 years ago, funds were raised to help fight one of the greatest social evils of all time.

Creator / originator

Granville Sharp, Chairman of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

Summary / objectives

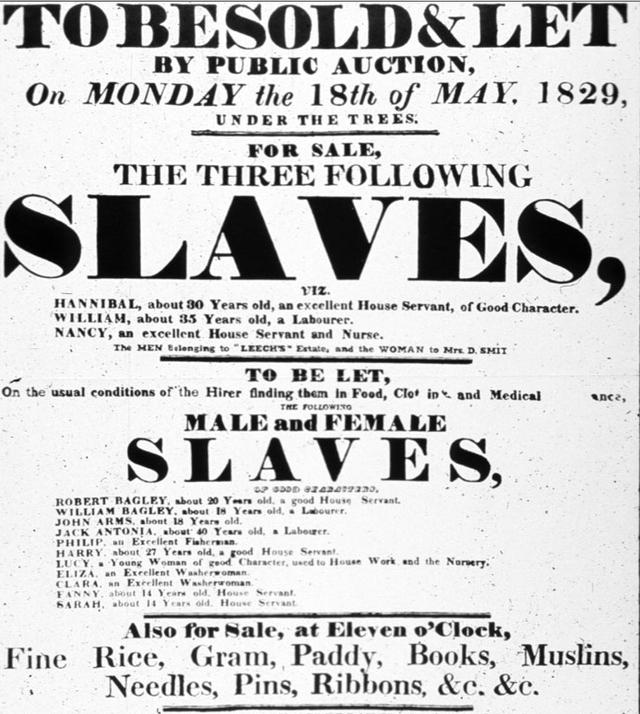

There can have been few greater crimes against humanity than the slave trade, which was rampant between Africa and the new colonies of North America in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Equally, there can have been few greater causes to raise funds for than the campaign to abolish slavery. This draft letter is recorded in their minute book and appears to be a copy of what would have been sent to members of the Society, asking them to cough up.

Background

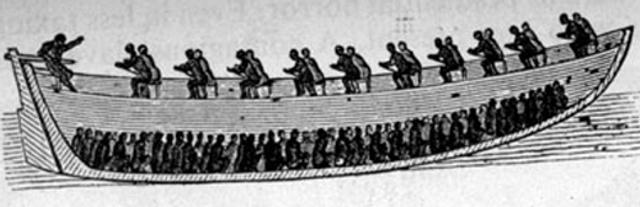

In 1787 Granville Sharp and his friend Thomas Clarkson decided to form the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. Although Sharp and Clarkson were both Anglicans, nine out of the twelve members on the committee were Quakers. Influential figures such as John Wesley and Josiah Wedgwood also gave their support to the campaign. Thomas Clarkson was given the responsibility of collecting information to support the abolition of the slave trade. This included interviewing 20,000 sailors and obtaining equipment used on the slave ships such as iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, thumbscrews, instruments for forcing open slave's jaws and branding irons. In 1787 he published his pamphlet, A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition.

But the cause of abolition wasn't to be quickly achieved. It took 20 years to achieve the passing of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807, which didn't actually abolish slavery, it only prohibited British ships from being involved in the slave trade. After this Act was passed Sharp joined with Thomas Clarkson and Thomas Fowell Buxton to form the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery. The title itself seems to indicate a lack of urgency. A new Anti-Slavery Society was formed in 1823. Members included Thomas Clarkson, Henry Brougham, William Wilberforce, and Thomas Fowell Buxton. Two years later, women such as Elizabeth Pease, Anne Knight, Elizabeth Heyrick and Mary Lloyd began forming women's Anti-Slavery Societies. In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. The leadership of the organisation attempted to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet and William Wilberforce gave out instructions for leaders of the movement not to speak at women's anti-slavery societies. The Female Society for Birmingham had established a network of women's anti-slavery groups and Heyrick's pamphlet was distributed and discussed at meetings all over the country.

In 1827 the Sheffield Female Society, became the first anti-slavery society in Britain to call for the immediate emancipation of slaves. Other women's groups quickly followed but attempts to persuade the leadership of the Anti-Slavery Society initially failed. In 1830, the Female Society for Birmingham submitted a resolution to the National Conference of the Anti-Slavery Society calling for the organisation to campaign for an immediate end to slavery in the British colonies. In an attempt to persuade the male leadership to change its mind on this issue, the society threatened to withdraw its funding of the organisation. The Female Society for Birmingham was one of the largest local society donors to central funds, and also had great influence over the network of ladies associations which supplied over a fifth of all donations. At the conference in May 1830, the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to drop the words 'gradual abolition' from its title. It also agreed to support Sarah Wedgwood's plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition. The following year the Anti-Slavery Society presented a petition to the House of Commons calling for the 'immediate freeing of newborn children of slaves'. The Anti-Slavery Society was disbanded after the Abolition of Slavery Act was passed in 1833.

Special characteristics

In its formality, the 114-word single sentence of this solicitation has a distinctly quaint character.

Influence / impact

Not known. Slavery was eventually abolished, at least in the common form that was practised at that time, but not fully until 1833.

Merits

An historic instance of early fundraising.

Final notes

Note on the provenance of this letter and also the Eihei Dogen letter, from Mal Warwick

'Friends and colleagues competed to pass along to me the world's first example of a direct mail fundraising letter. I thought I'd hit the jackpot last year when writer Adam Hochschild presented me with a photocopy from the Minute Books of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, minutes of the meeting of October 7, 1788. Imagine my surprise, then, to receive a much older but far more contemporary-sounding direct mail appeal from San Francisco Bay Area fundraising consultant Lisa Hoffman. Lisa works with the San Francisco Zen Center, and there she encountered a translation of an appeal sent to Buddhist monks throughout Japan in 1235 by Eihei Dogen, monk of the Kannondori Monastery(The letter was translated by Michael Wenger and Kazuaki Tanaka).

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image