CDE project 6 section 5.1: a communications practitioner’s view of emotion in fundraising.

From CDE project 6: the use and misuse of emotion, section 5, the inspiration business, article 5.1

- Written by

- Mark Phillips

- Added

- June 26, 2017

Click here for the full contents for project 6: the use and misuse of emotion.

A communications practitioner’s view of emotion in fundraising.

by Mark Phillips

My brief for this opinion piece was simple and direct. How should emotion be used in practical ways across all channels to enhance the donor experience? Can better use of emotional storytelling, as opposed to ever more persistent asking, really improve the donor experience and, if so, how?

Let’s try a thought experiment. Take a charity. Perhaps one you work for, or one that you support. Stop for a minute and create a picture in your mind of what would happen if they ceased to exist.

Did you see toxic waste leaking onto the surface of a once beautiful blue sea with birds struggling to break free of the oily, poisonous mess? Or perhaps you struggled to deal with the thought of neglected or abused children with no one to help them? Maybe you saw the hopelessness and pain of those faced with a disease that has no cure?

How did it make you feel? Angry? Sad? Frightened? Perhaps, all three?

I’m pretty sure that your brain didn’t start conjuring up images of graphs demonstrating how many species might be lost or how the mortality rate of infants might increase. Your reaction was stronger than that – it was emotional.

And that’s exactly how we need donors to feel when they engage with us.

When faced with some of these fundamental problems, our immediate reaction is not to put them into some sort of global or historical context. Instead, we have a visceral, physical reaction that can move us to tears or start our blood boiling.

It is that feeling that drives philanthropic giving.

I’ve chosen the word ‘philanthropic’ with care. Because it means giving is undertaken freely with real concern for a cause.

Because, as fundraisers, that is what we want; donors who are so emotionally engaged that they will fund the causes we fight for until a problem is overcome.

And far too much modern fundraising fails to grasp this point. Many of the techniques that have been employed over recent years simply don’t move people emotionally in a sustainable way. At least, not in the direction we want.

Listen to donors either through research or complaints, perhaps via the comment sections on newspaper websites or on our TV screens and you’ll hear a large number of people who are unhappy.

Not with the fundamental work of charities. There are precious few people campaigning for an end to cancer research and no one advocating the neglect of children.

They are upset with how we have chosen to communicate with them and how we treat them – to the point that they started voting with their wallets. However you look at individual fundraising, there has been negative growth in recent years. Indicator after indicator shows that fundraising is in the doldrums. And we are likely to be stuck here for a fair number of years to come.

Alongside this, we've seen a drop in trust.

If we look at the reasons why, we’ll see the use and misuse of emotion played a big part.

To help explain why, we need to go back to the late 1990s when two things happened to dramatically change the fundraising landscape.

The first was the introduction of paperless direct debits. This fundamentally changed the role of advertising – allowing direct sign up to a regular gift when a donor was spoken to on the phone. It might sound rather quaint but, before then, if a donor agreed to a direct debit you had to send them a mandate to sign. And, as you might expect, less engaged donors tended to forget to complete and return their forms.

Second was the massive commercialisation of face-to-face fundraising.

Combined, both techniques allowed charities to sign up regular givers without going through the process of engaging them first. Television didn’t really start flying as a recruitment medium until the very low-level price points of £2 to £3 a month were introduced. Once that was in place the two approaches meant that pretty much anyone was a prospect for any charity.

But why did this create a problem when the techniques generated thousands of new regular givers?

It was because the use of emotion changed.

Rather than use it to engage and drive positive action, we switched our focus to use emotion to get someone to sign a direct debit. The difference is huge.

Engagement takes both time and effort. Regular giving used to be a prize that you worked towards. Not only did you have to identify the best prospective donors, you had to bring them close to you. Copy was long, packs were detailed and the most successful communications demonstrated to donors that they were needed and appreciated.

But the introduction of the paperless direct debit changed the rules. Now the prize was the telephone number – preferably lots of them.

What followed first was a drop in the cost of giving, for the donor. Giving to charity does not have a fixed price. In effect, the donor determines how much they will pay to resolve a problem that concerns them.

And as we’ve always known, it is much easier to get a very low level gift than a large one. And the less you ask for, the more prospects you gain. So we saw the development of charity advertising that positioned the sector as the equivalent of the high street pound shop. Change the world for just £3 a month became the near ubiquitous call to action. Donors called in and signed up to a direct debit in large numbers.

As the range of charities adopting this strategy grew, prices dropped even lower to a period around 2013 and 2014 when trains and TV screens were dominated with ads asking for a one-off gift of £3 for such things as mosquito nets, payment for helpline calls and inoculations.

But, as we have seen, the thousands of donors who signed up to a low-value regular gift or texted in their £3 didn’t expect what came next.

After the lightest of thanks, phone calls arrived asking for a regular gift and upgrades. And this is when the use of emotion changed.

Rather than helping donors feel good about what they were doing, charities used what I describe as the guilt/cost proposition. ‘If it costs so little how can you say no?’ became the driving approach. And if donors said no they were asked again and again. And then, as likely as not, called again a few months later with the same approach.

The techniques used on the street were not a million miles away from this model.

And though some people signed up happily, others did so grudgingly. Others refused and became frustrated with what they saw as charities trying to make them feel uncomfortable. In Bluefrog’s research we saw a growing sense of unease that fundraisers wouldn’t take no for an answer.

The attitudes of donors were reflected in what happened to attrition rates. As the numbers of donors who were cancelling their direct debit within a few months of sign-up grew to 50 per cent and beyond, it became apparent that donors weren’t interested in the sort of relationships we wanted and started signing up because it was emotionally easier to cancel than to say no.

Rather than being proud they had made a stand against injustice and poverty, donors were reporting they felt pressurised and guilty. And their emotional reaction was anger.

It wasn’t just on the phone either. Charities were asking more often through direct mail too. The advice from some consultants was to ask more often to raise more money. And for some charities, it worked. But it might be asked if they really paid enough attention to how this was making donors feel? Particularly when these approaches were adopted by huge numbers of charities.

The result was that a significant number of donors came to associate charities with negative emotions. Repeated asks made them angry. Consequently, though a few charities may have benefited from these techniques, the sector as a whole suffered.

In other words, as donors didn’t get any emotional satisfaction from charities they realised they wouldn’t lose anything if they stopped giving – particularly if they could blame the charities themselves.

This point seems to have escaped analysis. It can be summed up by a conversation I had with a journalist. He wasn’t involved in the charity stories that ran in 2015, but he was aware of them.

He refuted the idea that critical stories were part of an orchestrated plot to undermine charities. Instead he suggested that charities were to blame for their misfortune because they had probably targeted a journalist (or their parent) to the point of irritation. A discussion with colleagues would have resonated across the editorial team and the investigations followed. When the stories made the front pages readers believed them because they had experienced the behaviour themselves.

So if the misuse of emotion got us into this situation, how can we use it to both re-build relationships and get our fundraising back on track?

Learning from another fundraising sector

It might be an idea to learn from another fundraising sector that was untainted by the 2015 media storm – universities.

The university sector remained insulated from the fall out behind that summer’s crisis. On the surface, that might be surprising. They are a very active sector that raises a significant amount of money – particularly amongst higher-value donors.

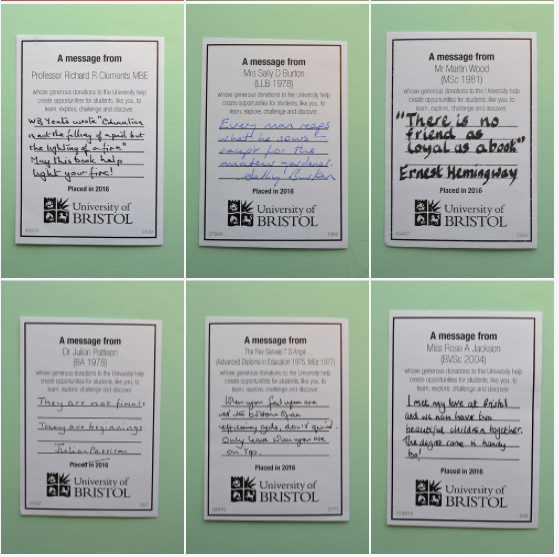

Rosie Dale, head of communications and regular giving at the University of Bristol, has explained why they are different.

As a university we only have a finite group of potential supporters. That’s our alumni – the people who have graduated from Bristol. And we only see a small increase of prospects once a year when another group of students graduate.

Because of that, our focus as university fundraisers is on developing relationships with our alumni via communications that reconnect them with their university. We identify those who engage and our asking is concentrated on those who want a relationship with us rather than those who don’t.

We also take the view that all alumni are part of the extended Bristol family. They made Bristol what it was and they all have the potential to help to make Bristol what it will become – whether that is as an ambassador, a volunteer, or as a donor. So rather than just looking at what we can do to make them give, we look at how we can bring them closer to their university on an emotional level.

One of the key things that came out of our discussions with alumni – via telemarketing, one-to-one meetings and through surveys – was that there was a significant element of pride in having attended Bristol, so we gave them more things to be proud about.

This included world-leading research, great facilities and details of talented prospective students who needed financial support to follow in their footsteps. And we also showed them how they would benefit, as alumni, from being a donor - through enhanced reputation and status from having attended a university that was achieving great things.

To build on this we wanted to connect them with the Bristol of today whilst at the same time evoking reflections on how being a Bristol graduate had changed their lives and played a significant part in making them the people they have become. So, rather than just asking for support, we asked them to write a message of encouragement or advice to a current student on a bookplate which would be placed in books in the library for hundreds of students to see and be inspired by for years to come.

Approximately a third of our alumni donors engaged with these inspiring, warm and heartfelt messages filled with reasons why Bristol matters. This helps to give us important insight not only into those that might be willing to support us further, but also how to further engage with these alumni and those who are not yet donors. Developing these relationships can take many years, but the result is long-term, loyal supporters.

If we get someone’s attention we want to use it to engage with them meaningfully and that can only be achieved if we connect with them at an emotional level.

Connecting at an emotional level

Rosie is right. Emotional connection is essential to any successful fundraising campaign. And recent research has identified just four base emotions. These are:

- Happy

- Sad

- Afraid/surprised

- Angry/disgusted

The last two are closely linked emotions in pairs as researchers suggest differences are the result of relatively recent social constructs rather than being part of the long-standing human psyche

So how should we use this information?

We need to remember that for all our technological advances, in terms of human history, we are not more than a handful of generations from living in the trees. And emotions still dominate our decision-making process.

As the neurologist and author Dr Donald Calne, author of Within Reason: Rationality and Human Behaviour (Pantheon Books, New York, 1999), explains ‘The essential difference between emotion and reason is that emotion leads to action, while reason leads to conclusions.’

And those actions happen pretty quickly, often within a few seconds. And this influences how we learn. Dan Hill, author of Emotionomics (Kogan Page, London, 2010) has shown through neural imagining that experiences actually rewire the brain. As a result, past experience predisposes us to take action when presented with a similar stimuli.

As animals, that system gives us an advantage because it makes the next action more intuitive.

As donors, when we pick up the phone and hear that short delay before an unknown voice kicks in asking for us by our full name, it places our brain in decision-making mode. If you’ve had unpleasant experiences with telephone fundraisers in the past, it’s highly likely you are ready to say no before the first sentence is even out of the caller’s mouth.

That’s not a good situation for any fundraiser to be in. Particularly if the only way a no can be turned into a grudging yes is via the use of negative emotions.

Using emotions to engage

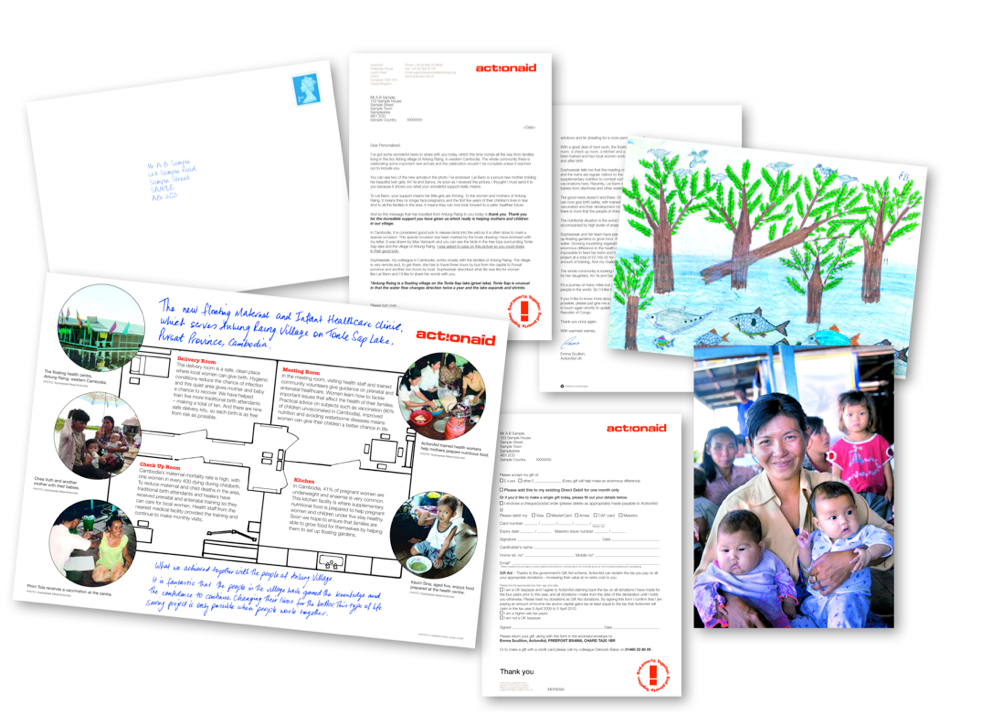

ActionAid is an INGO that uses child sponsorship to raise funds for much of its work. Because of the nature of sponsorship, ActionAid traditionally retains supporters for many years.

As well as having loyal donors, analysis indicated that a significant number were relatively wealthy and may well be able to give much more than their monthly sponsorship donation.

In 2001, the fundraising team made a strategic decision to focus on this group of supporters to see if they could improve their relationship with the charity and raise additional funds.

The first stage of the programme was simply to produce appeals that asked for larger gifts, but with success the importance of this approach grew. As Amanda Santer, who was head of retention and donor development at ActionAid, explains:

We knew that one of the reasons people chose to sponsor a child was because they wanted more than a financial relationship with a charity. And we used that knowledge to build our strategy.

It first manifested in the creative work. Rather than producing printed leaflets, everything was created to demonstrate authenticity. We described the projects in the form of a funding proposal rather than clever creative ideas. Pages would be annotated with hand-written notes, photographs would be attached with paper clips and post-its were used to highlight important sections. Everything went out in hand-written envelopes and we used a stamp. The phrase we coined to describe it was ‘inside track’.

We used this approach because we wanted to show donors how important they were. Traditional charity materials are obviously produced for mass communications. Our approach was to show donors they were important as individuals.

Again, our response rates and average gift jumped up. And the feedback from supporters was that these appeals actually made them happy. Happy that they were being treated as intelligent partners in development, happy that they could see that they were achieving something concrete with the donations and happy that they were changing people’s lives.

What was so remarkable about ActionAid’s programme was that they started to receive donations to their thank-you programme. They put real effort into making these as special as their appeals. Some were sent from overseas. They chose to delight supporters with photographs, ‘on-the-ground’ reports and children’s drawings. One particular thank you generated a response rate of 27 per cent – without a donation form or a response envelope. And that drove the next development of the strategy. As Amanda explains:

Once we had began to build a very high level of loyalty, we spoke to donors and asked if they would like to commit to long-term support. We explained that that they would be supporting ActionAid’s broad work on human security through a range of projects, but we promised to keep sending the same high quality feedback. Two-thirds of our highest value supporters signed up to a regular gift, with many increasing the value of their support by up to 50 per cent. And they kept giving cash too.

The fact was, they enjoyed hearing from us, in fact donors often called to speak to us about the work. We didn’t upset them or make them feel guilty. We worked to provide the supporters with a clear role in bringing about change. They felt part of what we tried to achieve and celebrated the success with us. Ultimately we focused on helping them reach their philanthropic goals. That meant we didn’t need to drive negative emotions. To date it is the most successful programme I have ever worked on and the one I am proudest of.

Ten tips for using emotion in fundraising

Though fear and anger can drive giving, they can’t continue to function without being offset by emotional reward. It’s a little like seeing a film that is just about pain and suffering. It soon becomes unbearable. The successful storyteller knows that there must be elements of relief before we have a conclusion that offers us a satisfying emotional reward.

We should also recognise that few of us like fear or anger. We instinctively tend to avoid environments or situations that drive these negative emotions. A fundraising environment that induces negative feelings is never going to be one that donors will actively want to inhabit.

So how can fundraisers best use emotions in fundraising? Here are 10 tips:

- Communications that create fear and anger will drive action, but long-term commitment is generated by organisations that offer the most potent means to tackle these negative emotions.

- People want to feel good about giving. They want to know they have made the right choice, that they are recognised and that they are connected to a like-minded group of people.

- People are more likely to be persuaded to act by those who make them feel good about giving. Endorsements from people they trust, value, or recognise can be very powerful.

- Generating feelings of guilt is a short-term strategy that loses power over time. Guilt initially makes people feel sad which they resolve by giving but this will turn into anger if used too often.

- People often give to prove they are ‘good’. Do not confuse this desire to look and feel good with connection to a cause. These donors are rarely loyal to specific organisations and will learn to avoid the charities that don’t take no for an answer.

- The thank you is the key part of any fundraising programme. If the recruitment device is the ‘box’, the thank-you piece is what’s inside. The more personal and thoughtful the thank you, the better.

- Poor treatment such as getting someone’s name wrong, delayed thanking (or receiving none at all) impacts on a donor’s self-worth. The thought that they don’t matter creates negative thoughts.

- Avoid donor regret by addressing donor needs after a donation. If a donor doesn’t see how they have made a difference with their gift, it creates a feeling of loss, which they can explain away as inefficiency on the part of the charity or their own ‘stupidity’.

- Do not think that barriers to giving can be overcome through aggressive, rational arguments. When someone appears unsure about giving it is because they don’t feel emotionally close enough to give.

- When donors first give, make the charity accessible to them. Welcome and reward curiosity.

A final thought

Emotional fundraising is about recognising the emotional needs of donors and answering them rather than exploiting them. The evolutionary process gave us feeling before thinking. That means in order to build long-term support, we must connect with donors emotionally first and then provide rational support. As Dan Hill reminds us: ‘facts are malleable but our gut instincts are unyielding.’

© Mark Phillips 2017