CDE project 6 section 4.2: The positives and negatives of emotional fundraising

From CDE project 6: the use and misuse of emotion, section 4: emotions and donors, article 4.2.

- Written by

- Jenny-Ann Dexter

- Added

- January 12, 2017

This article was originally commissioned as part of project 6 of the Commission on the Donor Experience, The use and misuse of emotion. The project will be published in its entirety in the spring of 2017, though a few of the articles will be available before then, to whet your appetite. The full contents list announcing all 30+ parts of the project will be published on SOFII in the next week or two.

CDE project 6 is organised by Ken Burnett. Any comments or questions regarding the project should be sent to him here.

The positives and negatives of emotional fundraising

By Jenny-Anne Dexter.

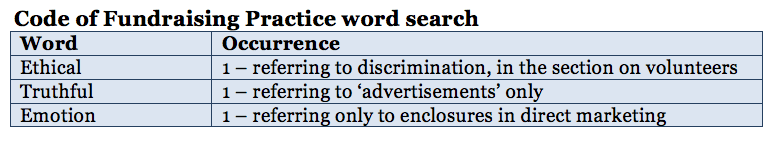

Before we think about emotion, we need to recognise that there are some limits to what we are able to do, according to various regulations and codes to which we are bound. There is much in the Code of Fundraising Practice, for example, regarding misrepresentation and offence, but it reads more like a guide to avoiding legal action and negative publicity rather than focusing on the basic, universal responsibility of fundraisers to promote good standards. Thus, more a set of rules than a code.

Could the Code be more directly mindful of our emotional relationship with donors?

In its annual report, the Advertising Standards Authority says complaints against non-commercial advertising – most of which was produced by charities – rose by 16 per cent in 2014; 2,466 complaints about 933 adverts in 2014 compared with 2,127 complaints about 922 adverts in the previous year. The ASA has said, ‘traditionally, we’ve granted more leeway to these types of ad because of the importance of the issues they are raising awareness about.’ The main theme of complaints has been related to ‘harrowing’ or ‘disturbing’ content or images. This trend has yet to fade out – there were 219 complaints about an advertisement by British Heart Foundation last year, the sixth most complained about advert of the year. And, of course, the press doesn’t ignore those complaints.

However, outside the remit of the ASA, powerful images can become a huge force for good, such as three-year-old Alan Kurdi being pulled from the Mediterranean Sea. The international outcry caused national leaders to commit to more support for refugees in several countries across Europe, although the impact didn’t necessarily last. But was it because this was a news report and not a charity appeal that it wasn’t seen as manipulative in the same way that the RSPCA’s images of animal abuse often are? Both are real, no doubt about it, but the reaction of the public was very different in each case. When people saw the image of a small boy who had drowned they found his fate unacceptable and many relief charities saw donations flood in. The other, from a respected charity, was simply irresponsible and offensive to some. Do people simply trust the news more than charities? And if so, what can we do to change that?

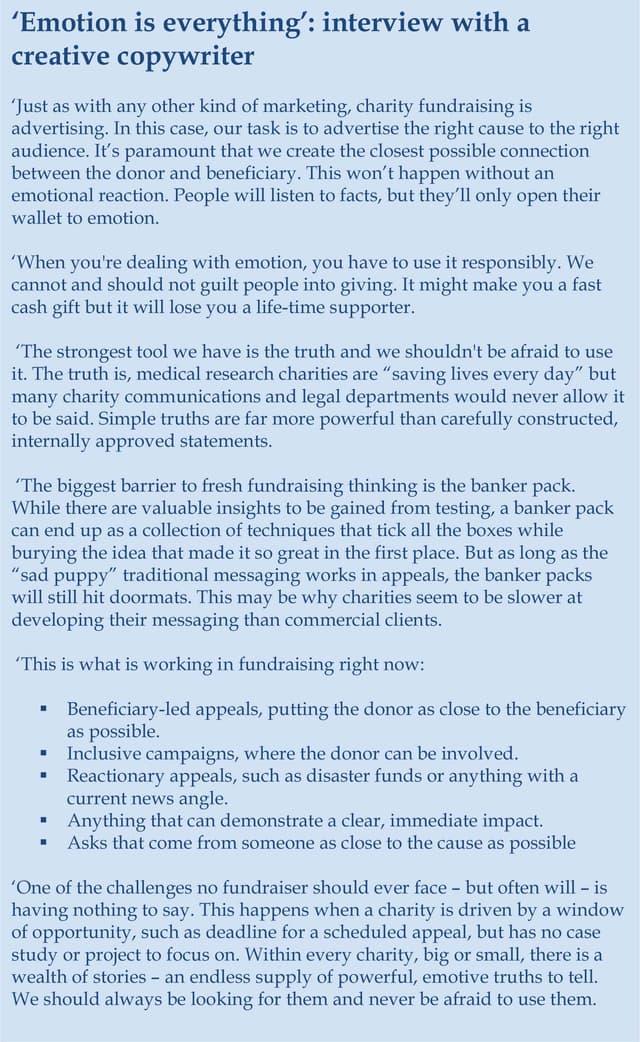

And so to emotion and the ways that charities can and do elicit a response from donors. Humour, sad stories, happy endings – they can all work when done well. But what are the pitfalls? How much is too much? Who is the judge of that and what is the measure of it?

If we can tell the story in a way that grips someone emotionally, then we know we have a chance of them hopefully considering supporting our cause.

Tanya Steele, interim chief executive, Save The Children

Save the Children’s No Child Born to Die campaign has increasingly put beneficiaries at the very core of its creative messages. The most recent videos have particularly identified individual beneficiaries, making their dreams and aspirations the focus of the story, directly linking donor and outcome clearly.

The theme of NSPCC’s Alfie the Astronaut came from a survey that found that one in seven British adults achieved the job they dreamed about when they were children. The story is of a child visualising his dream future as an astronaut whilst actually having suffered abuse at home. The message is that ‘your donation can take a child anywhere’ – clearly aspirational, although not particularly urgent. For me, it is a much poorer example, aspirational fundraising where the outcome isn’t necessarily clear or quantifiable enough. A little too woolly.

Oxfam’s computer animated Be Humankind campaign ads created a chasm between viewer and cause, the high drama detracting from the very real-life issues at stake. Studies on post-humanitarianism described them as examples of ‘chronotopic estrangement’ – essentially making normal things in our reality, such as places and people, unfamiliar.

Added to that, the embedded theme of collectivisation may have made it too difficult for a viewer to think it was possible to make a difference on one’s own. Too much ‘we’ not enough ‘you’ perhaps? As an attempt to tackle public apathy, it didn’t really succeed. Another example of this is The Pilion Trust’s #fuckthepoor viral, referenced later on.

The Be Humankind campaign directly addressed neither the donor nor the beneficiary. It didn’t quantify or qualify the scope of the actual problem and didn’t offer a clear solution either. Ironically, this is what Oxfam said about the campaign:

It is much more direct in terms of what we are saying. In the past we have used images of people who live overseas... People can have a tendency to say 'what does that have to do with me?' They can feel a sense of uselessness and we want to bridge the gap.

Julie Wood, former director of corporate communications, Oxfam

Save The Children’s recent campaign – Most Shocking Second a Day took the plight of a Syrian child and made it a reality in a British setting, to bring the cause closer to home for the viewer. The viral has been viewed online more than 50 million times and won the Golden Radiator Award. But has it been successful? Ironically, some have described it as ‘unrealistic’ because it depicts a fictional situation, but would donors still care as much if it was depicting the reality of that situation through the eyes of an actual Syrian child?

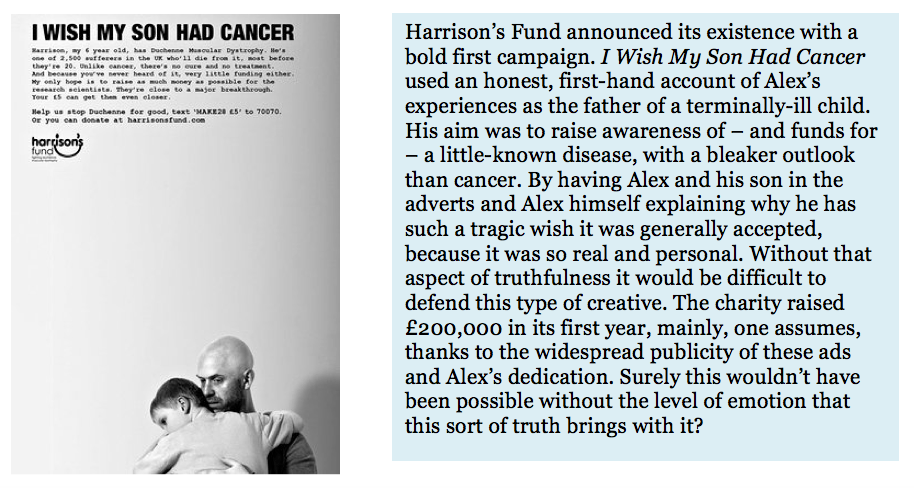

Brutally honest campaigns are those that really sit closest to the edge. Those that take a very real, difficult situation and tackle it head on, without having to pile on extra emotion with soft, sad music, or other affectations.

Being blatant is one of the only ways small charities can gain the same traction and voice that larger organisations do.

Alex Smith, founder, Harrison's Fund

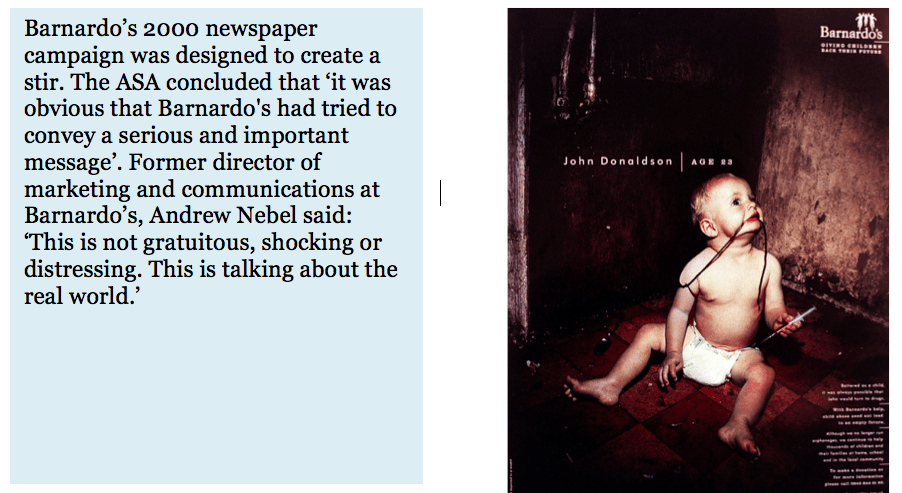

There is an argument that smaller or younger charities have much more to gain by launching a shocking or challenging ad designed to provoke strong emotion. The value of press it can generate could really put it on the map. Often this is, whether intentional or not, because there is a provocative, guilt-trip side to the messaging.

10.10’s video, to highlight the effects of ambivalence in the face of climate change only served to further alienate their cause, according to the comments made about the video on YouTube. Jeff Brooks, author of The Fundraiser’s Guide to Irresistible Communications (Emerson & Church, USA) wrote of the viral on SOFII’s Bad Ads Showcase, saying, ‘They’ve handed the climate change sceptics a perfect reason to claim that environmentalists are anti-human extremists. They’ve done lasting, maybe irreparable, damage to their own reputation and to their cause in general.’ Quite right too. This sort of video makes environment enthusiasts, like me, look like nutcases.

The Pilion Trust’s provocative #fuckthepoor viral ad challenged people’s assumptions about the values they believed they had. If asked, most would say that they do want to help the poor but, during the course of filming, not one person came forward to put money into the bucket to ‘help the poor’ and when faced with a message of ‘fuck the poor’ it was challenged immediately and constantly.

Charities are often told that to attract attention they need emotive appeals, but guilt-tripping can have the opposite effect.

The Guardian, 2 Sept 2013

The negative fall-out for The Pilion Trust was widespread. The charity suffered loss of government funding, half the management team quit and it suffered difficulty in replacing trustees. Despite 4.7 million views, which no doubt did wonders for the charity’s visibility, many now think that the charity is too confrontational and unpredictable to condone. Direct income from the campaign did not cover its cost, although it did provide The Pilion Trust with a small yet deeply dedicated new group of donors. Average gift was high and engagement has led to other benefits such as business partnerships and visibility for its advocacy work. Some of the outcomes from #fuckthepoor suggest that placing a strong emphasis on emotion could lead to short-term wins, but that by successfully tapping into a person’s values you could find more long-term and, ultimately, valuable support.

(As an aside, the experiment was replicated across the world. In India, where for cultural reasons, they used a ‘kill-the-poor’ message, it was greeted with frightening enthusiasm, with people asking how it would be done, even making their own suggestions! When the message ‘help the poor’ was used passers-by became aggressive and the experiment had to be called off to protect the safety of those involved.)

Bambos Neophytou, co-author of the book Guilt Trip (John Wiley & Sons, UK, 2010), believes that although guilt can make an impact in terms of highlighting a problem or need, it is less effective in prompting action. ‘Positive emotions tend to be more effective in behavioural change', he says. He adds that another danger with guilt is that there is a saturation point and that many of us are less receptive to the kinds of appeals that play on guilt than we used to be. That might explain at least some of the failure of Be Humankind or The Pilion Trust in connecting with some audiences.

In 2013, St John’s Ambulance stated its intention to continue to release shocking content, after one Twitter user declared she’d rather be scared of an ad than be scared she couldn't save a life. But do those intentions also apply to their fundraising campaigns? Some charities can prove that income declines sharply following a softer campaign and many choose to run both types.

When it launched a campaign featuring a baby left to cry in a cot, the NSPCC faced a backlash from those who found it distressing. But former director of fundraising Paul Farthing said that at the time the charity had tested a range of approaches and advertising styles for television and its observations were conclusive. ‘Direct response television campaigns such as the one featuring baby Miles in a cot, that clearly and simply state the problem of child abuse and the need for people to donate in a clear and powerful way, have been proved to resonate most with our donors’.

BHF’s Dead Dad ad – heart disease is heartless depicted a sadly all too common experience, that of a young boy learning of his father’s sudden death. Over 200 complaints were made to the ASA, which commented ‘many of the complainants have referred to a personal similar experience that occurred within their family.’ So was it just too close to home for some? As a response, BHF’s website recommended bereavement charities the viewer could contact if they are emotionally affected by the advert.

…brings to life the unfortunate reality…

BHF website

Another BHF campaign Last Words features real people, with real stories of their last words with loved ones before they died from heart disease. This one didn’t receive complaints.

But how much is too much?

The Fundraising Regulator’s Code of Practice says:

- Organisations MUST NOT* send a communication that is indecent or grossly offensive and that is intended to cause distress or anxiety.

- Fundraising organisations MUST be able to justify the use of potentially shocking images and give warnings of such material.

An audience expects honesty from a charity, but can they handle it? The honest truth is that children are dying from treatable diseases every day, the planet is suffering from our pollution and animals are being dumped and mistreated in every country of the world. We all know these things to be true, but when we present them in such a direct fashion the reaction isn’t universally positive. But can it ever be? If we are only upsetting people who were never going to give in the first place perhaps it doesn’t matter what we do. So, realistically we shouldn’t aim to be entirely free from controversy – as long as there is the Daily Mail, there will be ‘outraged from Beaconsfield’.

That is the thing about shock tactics in advertising, if you try to shock for the sake of it people see through it. If what you say shocks and is based on honesty and truth, it rises above.

Alex Smith, founder, Harrison’s Fund

Feed a Child’s video depicting a hungry black child as being treated like a dog immediately came in for such a depth of flack that its vital message on childhood poverty was completely lost. A posting of the video on YouTube by a disgruntled critic has racked up over 209,000 views, while the charity’s version on their own YouTube channel has only had 19,000 views to date. Most viewers couldn’t see past the apparent racism – especially those outside South Africa, where race relations are less clearly defined. Although the majority of us would support any effort to tackle this issue, it seems a large proportion of people all over the world were so turned off by the creative treatment that it completely missed the point..

Save The Children’s childbirth video (part of No Child Born to Die) collected over 600 ASA complaints, even though the newborn baby featured in the film survived. A million children die during childbirth every year – that’s a fact. Yet this child didn’t. Was it because the charity was afraid to take the truth too far? The 600 people who chose to complain to the ASA obviously felt more strongly about the advert being inappropriate than about the cause it depicted. Or did it simply undermine the integrity of the charity in their eyes? And, if so, is that permanent? Have their donations been lost forever?

The ‘willing suspension of disbelief’, to quote Coleridge, is acceptable in certain circumstances. The plot of a film, for example, can take any unrealistic turn and we accept it without question. What happened in the 10.10 video happens in a large proportion of action movies as standard. For entertainment purposes we are willing to go beyond the realms of reality, though when it comes to charity campaigns we seem to be less likely to take anything but the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. And yet, at the same time, we are not always able to accept the full facts. It really is a delicate balance. But real emotion best comes from that which we can clearly identify with – real people, real life.

The appeals used in this study were shown to a random group of friends and acquaintances, who were asked to write down their emotions immediately after watching each one. This was by no means an academic study but, once their thoughts and feelings were compiled, each viewer fitted nicely into one of two categories. Half were very analytical in their responses, the other half mentioned their feelings a lot more.

Despite not being particularly scientific, it did produce some interesting comments such as, ‘music was awful, too loud’ from several individuals about one DRTV advertisement. Three of the 10 campaigns did not elicit a positive response from either group. A further three fell into one of two categories – it either resonated with logical thinkers (related to Emotionomics’ ‘feeling component’), or emotional ones (related to Emotionomics’ thinking component’). The remaining four campaigns made a positive impact on both groups, affecting both those who needed to be emotionally connected to a cause and those who were simply looking for a good enough practical reason to donate.

Which one are you?

Which would you respond to?

Certainly emotional thinkers are very likely to donate in the short term, but are logical thinkers more valuable in the long term? Are they more likely to be a higher level of potential donor?

Some of the larger charities already run concurrent DRTV commercials which each serve to speak to a targeted demographic, to some degree testing the effectiveness of an aspirational message versus more emotionally powerful content.

Charities are hedging their bets. The stark reality is that no one size fits all – no one message will resonate with all people, but aiming an appeal at either heart or mind is usually better that trying to make an impact on both.

There is no unselfish good deed.

Joey Tribbiani

Yes, I’m quoting Joey from the hit TV series Friends. And how true it is. Our donors want to feel good when they give. Or at least to know they are helping to make the world a better place.

In this donor-centric time, a wise charity will seek to understand its donors in terms of their motivations rather than their demographic structure. For some charities, outrage at injustice is a key driver of support, for others it’s the ‘good-citizen’ or ‘faith-based’ driver. Money for Good, a segmentation tool developed by UK consultants NPC (New Philanthropy Capital) is the best way to begin investigating your donor database, if you haven’t already.

Jen Shang philanthropic psychologist and director of research at Plymouth Business School, says charities should unquestionably apply emotion to fundraising and campaigning. ‘Humans are made of a brain and a heart and people think and feel and that’s how real life is,’ she says.

If charities don't use emotion they might have a problem.

Jen Shang, philanthropic psychologist and director of research, Plymouth Business School

Academic research has actually identified that people feeling strong negative emotions make them unlikely to take responsive action. Shang adds that she has previously done research where she put a line of smiley faces on an appeal and people gave more because the faces made them feel happy (if only it were that simple).

Alan Clayton, fundraising guru, says that using negative emotions such as guilt doesn’t encourage long-term giving. Instead it is ‘reward emotions’ that enable people to enjoy giving and therefore provides the encouragement to do so. ‘The mistake charities make’, says Alan, ‘is that they keep going with the need emotion because it works short-term, but they don't put enough emphasis on the reward emotions.’

‘Poverty porn’, a term coined to highlight the overuse of hard-hitting images and stereotypes, such as the starving African child, remains the scourge of the charity appeal and is a perfect example of over-reliance on negative emotional impact. Of course most of those images are taken from real life but their overuse, not only in fundraising, but also in the news, has caused the majority of the public to become emotionally blind to them and therefore to the accompanying ask.

The Guardian has run a series of articles in recent years asking whether ‘shocking charity ads’ have lost their power to make an impact – whether positive or negative. Maybe it’s simply that, over time, the ability to shock isn’t as easy. It’s less likely that the mark can be overstepped – so how far have the goalposts moved?

Identifying this saturation point is the key. It can be seen in our blindness to charity collectors in the street – as illustrated so well by #fuckthepoor. ‘Poverty porn’ isn’t as effective as it once was simply because we are so used to seeing starving African children and abused animals. As donors we now want to know if we are making a difference. Are we, as fundraisers, satisfying the needs of the donor? One of the most likely questions is: will my gift make a difference? Can you show them the answer to that? Surely a donor who feels good after giving is one who is more likely to want to feel good in the same way again in the future. Guilt tripping or emotionally blackmailing donors into making a donation doesn’t make them want to feel like that again. More than likely they will actively avoid all charity appeals in the future, not just yours.

Kristoffer Kinge, vice-president of The Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ International Assistance Fund (SAIH) agrees that ‘these images that are shown in advertising and fundraising campaigns create apathy rather than action’, he says.

Emotion plus integrity equals brilliant fundraising, said Alan Clayton, which is absolutely spot on. But is that only one option? That depends entirely on what you want from your campaign. The Common Cause UK Values Survey highlights some potential issues with the simplicity of that quote. Common Cause Foundation conducted a survey of 1,000 people across Britain and found that although 74 per cent of respondents prioritise compassionate over selfish values, 77 per cent – even more – believe that others prioritise selfish values over compassionate.

In short, and put rather too simply perhaps, people are likely to expect the worst in other people, despite the goodness of their own convictions. A case of why should I if others aren’t? I have certainly found this true when trying to convince my colleagues of the importance of recycling. And this is particularly true when addressing perceptions of institutions, such as business and the government. It is likely that this value extends as far as charities.

Our collective decisions are based importantly upon a set of factors that often lie beyond conscious awareness, and which are informed in important part by emotion – in particular, dominant cultural values, which are tied to emotion.

Common Cause UK Values Survey

The survey also asserts that ‘people are sensitive to the values held by those they respect’, which may explain Bill Nighy’s appeals for Oxfam’s Syria Crisis Appeal. If Bill Nighy is asking, I'd better give. It isn’t clear whether Oxfam chose Nighy for his particular appeal to middle-class ladies of a certain age…

Dogs Trust’s #specialsomeone rehoming campaign culminates with a happy ending as a rescue centre dog finds his new owner, accompanied by a particularly sombre version of a usually uplifting tune. The need is illustrated, there’s a happy ending, the characters are identifiable. It certainly had an impact on me, a dog owner, and hopefully at least partly its target audience. But it wasn’t a real story and that much was obvious to the viewer. By contrast, much of their DRTV content is less softly charged when it comes to emotion, instead highlighting the urgency of the need.

Macmillan’s Not Alone support campaign piled on the emotion, really getting to the truth of how it must feel to deal with a cancer diagnosis. The message was that Macmillan are there to help, but there is no need to soften the message as the urgency would be lost.

Fundraising campaigns combine so many elements – their style, characters, messages, sounds all come together to try to elicit certain feelings and actions. Are we bearing all of these in mind when we put a campaign together? What do our donors want to know?

Being humorous, creative, or both, without over-simplifying the issues and also showing the structural reasons behind poverty, is the way forward.

Kristoffer Kinge, Rusty Radiator Awards and vice-president, SAIH

So what happens when humour takes centre stage? Movember’s Alley Fight campaign video may have been targeted at the difficult to reach young male demographic, but loses the point altogether. The victim – a brain-shaped lump of prostate cancer on legs – is unarmed and seemingly harmless, rooting through bins in a back alley as it is stalked and attacked by an angry, armed, moustachioed mob. It doesn’t seem to resonate with any other demographic and the rest of its audience is most likely left feeling less than charitable about that particular charity.

New Zealand charity CureKids enlisted comedy group Flight of the Conchords to write a song to support their cause. The resulting lyrics werypenned by children themselves, bringing the voices of those children in need directly to the ears of their donors. Needless to say, the song reached number one in the charts, raising NZ$1.3m as well as doing the charity brand no harm at al

Likewise the success of the BBC’s Children In Need and Comic Relief must be in part due to the frequent beneficiary videos featured during their television coverage. Additionally it provides the right mix of entertainment and cause. They use celebrities to influence the viewer (ad hoc giver, aspirational motivations), mixed with honest campaign videos, which appeal to the more emotional or rational viewer (thoughtful philanthropist, emotional motivations).

It may seem simple, but not everyone will be moved by an emotional appeal. Nor will everyone be moved by a funny story or fantastic statistics. People also assume things about themselves – they assume they are compassionate, they assume they do not respond to celebrity influence but our statistics say otherwise.

To use emotion in fundraising, the key seems to be to bring donor and beneficiary closer together, without creating a false narrative. This will develop a deeper and hopefully more meaningful, lasting connection. We, the charity, are the least important part of that. We are just the conduit.

And, finally, a word on accountability. Who is judging us? Whose opinion matters the most? Our first instinct is that it is the donor, though it is the ASA or the Daily Mail that seems to have the loudest voice. As long as our messages are conveyed with truth and emotion throughout, does it matter in the long term that one headline made a bit of a stir, or that 20 individuals – probably with very little intention of donating to the cause anyway – felt they needed to make an official complaint? In essence, your own donors will know if you are being untruthful. And if they don’t, the press will. And then we all will.

© Jenny-Anne Dexter/ the Commission on the Donor Experience 2016.