CDE project 6 section 3.2: the use and misuse of emotion

From CDE project 6: the use and misuse of emotion, section 3, the science of emotions, article 3.2.

- Written by

- Kiki Koutmeridou

- Added

- January 05, 2017

This article was originally commissioned as part of project 6 of the Commission on the Donor Experience, The use and misuse of emotion. The project will be published in its entirety in the spring of 2017, though a few of the articles will be available before then, to whet your appetite. The full contents list announcing all 30+ parts of the project will be published on SOFII in the next week or two.

CDE project 6 is organised by Ken Burnett. Any comments or questions regarding the project should be sent to him here.

The use and abuse of emotions in fundraising: a behavioural science point of view

By Dr Kiki Koutmeridou

Is there even need for emotion in decision-making?

For decades, many philosophers considered decision-making to be a purely rational process. Emotion and reason were treated as separate, with emotions considered a hindrance to decision-making.

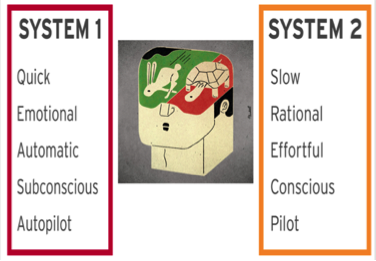

In his book Thinking fast and slow, Daniel Kahneman1 explains how decisions could be made by two systems:

The intuitive and emotional (fast) system 1, or the deliberate and rational (slow) system 2.

Emotions are thus recognised as having their part in decision-making. However, this doesn’t mean they should be included, or that their inclusion is necessary, or even beneficial.

Do you think emotions should be involved when making an important, life-changing decision such as buying a house or choosing a career? If you had the choice would you only base it on reason?

Only recently, philosophers, neuroscientists and psychologists have proved the extremely important role that emotions play in decision-making. In his first book, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain Antonio Damasio2, a leading neuroscientist, describes two neurological cases: Phineas Gage, a construction worker, who miraculously survived an accident that sent an iron pole through his head and Elliot E, who was left with damage after the removal of a tumour in his brain.

They both suffered injuries in the area of the brain (prefrontal lobe) that is now considered to be responsible for decisions in response to emotions. Even though their intellect or memory weren’t affected, they both began to behave like different people – unreliable, impatient – with signs of irrational behaviour. More importantly, they couldn’t feel emotions and they couldn’t make any decisions.

In one of his visits, Damasio asked Elliot which of the two dates for their next meeting would suit him best. It would take most people only a brief reflection to pick a date. For Elliot, this simple decision has become an impossible task. Half an hour later, when he still couldn’t reach a decision, he was interrupted with a suggestion that he accepted immediately.

Damasio concluded that these patients, when faced with situations that can lead to different outcomes, are unable to pick the most advantageous option for them. In his own words: ‘It is emotions that allow you to mark things as good or bad or indifferent and it is that kind of emotional input that they’re lacking3.‘

How do emotions shape our behaviour in our everyday life?

We’ve now established that emotions are essential to decisions and that they can also speed them up. Many decisions have pros and cons on each side. With reason alone, we’re unable to reach a conclusion; remember how Elliot still couldn’t choose between two dates after half an hour?

In some cases, emotions can lead to beneficial outcomes in complex decisions. Stock investors were asked to rate their feelings online while making investment decisions for 20 days; those who experienced more intense emotions had also the highest decision-making performance.4

All decisions involve predictions of future feelings. For any action we take, we don’t just rely on what we think but also on how we’ll feel about it. Our choice of dessert, for example, is based on our prediction that we’ll enjoy this one more than any other. This strategy is very effective because, in most cases, we can accurately predict whether we’ll like or dislike the outcome of our decision. But often we’re unable to predict the intensity or the duration of our emotions, which can lead to biases.

People in both the American Midwest and in California predicted that a Californian would be much happier than a Midwesterner. Based on their personal ratings, however, people were equally happy in the two locations5.

Inaccurate predictions of emotions also result from the so-called hot-cold empathy gaps: someone in a ‘cold’ emotional state fails to predict how she’d feel and act in a ‘hot’ emotional state and vice versa.

Visitors to a museum were given a quiz and as a reward they could choose between a sweet or the answers. Some were asked in a ‘cold’ state, before taking the test, when their curiosity about the answers wasn’t piqued: 79 per cent of them chose the sweet. Some were asked in a ‘hot’ state, after taking the test, when their curiosity was piqued: only 40 per cent chose the sweet. A third group was asked before taking the test to predict what they’ll choose after taking it: 62 per cent said the candy, proving our difficulty to predict and account for the impact of our emotions on our decisions6.

Visceral states like pain, hunger and sexual desire also elicit strong feelings that have a powerful and direct effect on behaviour, speeding it up towards a certain direction.

Male college students, in the privacy of their rooms, were asked a range of questions online about their sexual preferences and condom usage. Half of these students were asked to arouse themselves – yes, it’s exactly what you’re thinking… Based on their answers, these ‘excited’ students were twice as likely to engage in odd sexual activities and less likely to use a condom7

Outside the heat of the moment, however, we tend to ignore, or at least underestimate, the impact these emotions have on our behaviour. When you’re not thirsty, in pain, or angry you can’t accurately predict how you’ll behave when you are. This lack of insight means that we don’t take measures to deal with situations that induce these feelings and we end up behaving against our self-interests e.g. overeating, sexual misconduct.

Emotions as an ally to fundraising

One of the key lessons from behavioural economics is that our decisions don’t always follow a strict, mathematical logic. Think about pro-social behaviour: why would you give your money, or risk your life to help a stranger? It doesn’t make any logical sense, but it does make sense from a humane standpoint. The decision to help someone isn’t rational, it’s an emotional one.

A rational appeal advert on child abuse was tested against an emotional one, showing a young boy running away from his father in terror. The strong negative emotions that this appeal elicited increased feelings of empathy, which in turn increased helping behaviour8.

There’s an on-going debate whether positive or negative appeals are more effective. There’s seems to be a slight tilt towards negative appeals, but overall results are inconclusive. I bet you can all think of an upbeat appeal that yielded excellent responses and gifts, but also a negative one that had similar success.

Despite this difference of opinion there is consensus, even between academics and practitioners, that appealing to emotion – either negative or positive – is more effective than appealing to reason. An emotive story or picture brings the cause to life and affects behaviour with an impact that detailed facts about the increased need never will. If you’re a fundraiser this isn’t news to you, you’re aware how an emotional appeal triggers more helping behaviour compared to just sharing dry facts.

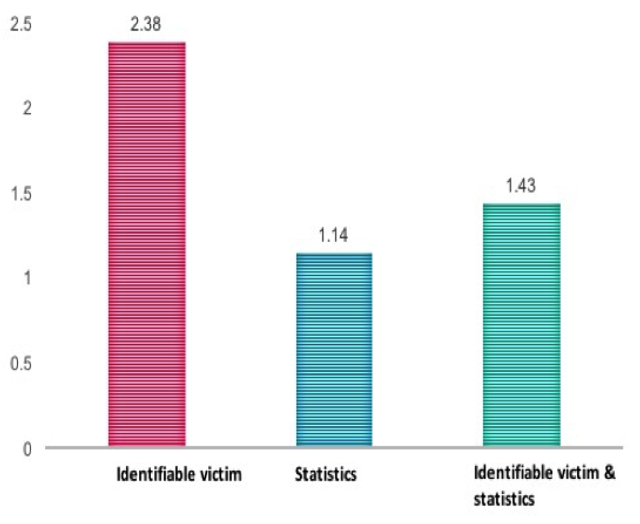

The identifiable victim effect9 illustrates this point. A story of a person in need induced much higher response compared to an appeal that only included statistical information, as shown in the graph below. This result is due to the increased feelings of empathy experienced towards the identifiable victim. The latter doesn’t even need to be human to trigger helping behaviour. One of the costlier animal rescues ever was to save the captain’s dog that was left behind on a tanker left adrift in the middle of the Pacific (Vedantam, 2010).

What’s still not fully grasped among fundraisers, though, is how damaging the addition of rational information can sometimes be.

You can see in this graph that even combining a personal story with statistical information reduces responses significantly.

This isn’t to say that facts and statistics should always be avoided. When an appeal is about supporting a programme, not a person, the addition of such information can increase responses. So, it’s not an in-or-out approach, but more a matter of when and how you use this type of information. If there’s a chance that it will diminish the emotional experience, then leave it out.

It is now believed that people give more towards an ‘identified victim’, not just because of the empathy this type of appeal elicits, but also due to the increased feeling of impact a supporter has. The addition of just a short paragraph on output and personal impact in an appeal significantly increases willingness to donate10.

The mere act of helping produces an inner satisfaction, a sense of ‘warm glow’. But, the knowledge that your donation has had an impact, that it changed a person’s life, is what transforms this ‘warm glow’ to happiness.

Is the donor’s happiness important? Obviously, not in the least because happiness from a pro-social act is a good predictor of future pro-social acts. As illustrated below, a positive feedback loop exists between helping others and happiness.

The happier I am, the more likely I am to help others and helping others has a positive impact on my happiness.

The impact that my donation has is a significant driver of this happiness.

Thus, stressing the impact of a gift to donors is crucial as it will initiate, or strengthen, this positive feedback loop between helping and happiness.

An emotion that is rarely considered but also affects helping behaviour is nostalgia. Appeals that managed to elicit this feeling achieved higher response rates11. Naturally, this result is more pronounced when the appeal evokes important memories for the person, rather than generic ones. It seems that looking in our past urges us to create a better future. This is partly because nostalgia, even though a bittersweet feeling, actually makes us happier. A glance to the image above will remind you of the direct link between happiness and helping. In addition, nostalgic thoughts typically involve memories with other people, thus increasing the closeness and empathy we feel towards others. This, in turn, increases helping.

When do emotions in fundraising backfire?

We’ve seen that both negative and positive appeals can boost fundraising. When it comes to positive emotions, like sense of impact, happiness, or nostalgia, go big. However, the use of negative emotions, like pity, sadness, or fear, requires more caution.

It’s true that extremely negative, or shocking, appeals catch our attention and create a ‘buzz’. Nonetheless, the indiscriminate use of extreme negative emotions by many charities can result in an emotional burn-out: people are exposed to so much suffering that they become cynical and less responsive.

Even within the context of a single appeal, if the intensity of negative emotions isn’t manageable, they might induce apathy; people might ‘switch off’ and enter a state of withdrawal and non-responsiveness. A negative emotion that shouldn’t be evoked under any circumstances, even in low intensity, is guilt. Yes, guilt motivates action in our every day life; we do everything we can to avoid it. This guilt aversion might motivate us to get out of the house during the weekend, despite how tired we may feel, to avoid feeling guilty later if we don’t. The same way, guilt might be effective in making people respond to a charitable appeal.

Think of this, admittedly extreme, phrase: ‘if you don’t respond a child that could have been saved will suffer’. The guilt we anticipate we’ll feel if we don’t respond motivates us to donate.

Now think of this, again purposefully extreme, phrase: ‘How fair is it that you have warm, healthy food every day while families around the world are starving?’ Once again, response will be driven due to the existential guilt experienced by the discrepancy between our well-being and other people’s suffering.

In some cases, a guilt appeal might be even more effective than a positive one: a research found that guilt imagery was more effective on intention to donate money and time to an animal welfare organisation than imagery evoking warmth 12.

However, this shouldn’t give license to fundraisers to use guilt – and definitely not abuse it. First of all, when such a tactic becomes obvious (just like my examples above), people will be irritated and become angry with the organisation. Even if donations did increase due to the use of extreme negative emotions, or guilt, you might want to consider the negative impact such a tactic might have on the organisation’s image.

But most importantly, guilt appeals should be avoided because, under these circumstances, a donation is based on selfish motives: the sole purpose of giving is to alleviate the guilt experienced in that moment. These appeals don’t nurture a long-term, positive relationship with the supporter as they fail to induce the positive emotions discussed in the previous section. After such a donation, I might feel relief because I won’t experience guilt, but it’s questionable as to whether I’ll experience ‘warm glow’ or happiness, emotions which perpetuate giving.

What are the big issues in fundraising? A personal view

Issue 1: appealing to reason using facts and stats when the focus should be on emotion

As mentioned before, our decision to help isn’t based on any premeditated analysis of pros and cons. It’s mostly driven by our emotions. We donate because we’ve been moved by a personal tragedy; we give because we have an emotional connection with the cause; we help because we feel responsible, or guilty. A successful appeal is one that touches a nerve, triggers an emotion, not one that makes a rational case.

Nonetheless, charitable appeals are still trying to motivate people using logical arguments because it’s counter-intuitive not to. Sharing facts and displaying charts feels like the right way to increase helping behaviour. Yet, it’s not. Employing logic could even be detrimental. We’ve seen how the mere inclusion of statistical information is enough to annul the impact a personal story has on giving behaviour.

Issue 2: decreasing the feeling of personal impact by increasing the scale of the problem

Another common fundraising strategy, relating to the above issue, is stressing the size of the problem: appeals emphasise the international, or global, scope of the matter, or mention the millions in need of help.

Once again, this is based on the premise that helping is a calculated, rational action. It’s what our intuition dictates: the bigger the problem, the more people will help. It’s a logical argument but, as a strategy, it fails because it totally neglects human emotions.

If a problem is way outside our capacity any donation we might make, especially a small one, will feel like a drop in the ocean. The perception of our personal impact is diminished and any hope of making a difference vanishes. Such an appeal reduces likelihood of action while it leaves a bitter after taste.

Issue #3: outside their use in fundraising appeals, the donor’s emotions are entirely overlooked.

The donor’s emotions are usually only considered in the context of individual appeals and how they could increase their success. How a donor feels, though, should be taken into account throughout the entire fundraising experience.

This brings us to a couple of questions that are hugely neglected in fundraising, but should be at the centre of all programmatic and strategic decision-making:

- How do fundraising practices make the donor feel?

- How can the donor have the best, most positive experience?

Fundraisers are mostly concerned about doing what’s good – or at least what is believed to be good – for the charity. At the same time, they create a lousy experience for the donors: any irritation caused by the over-solicitation is neglected; any boredom elicited by the information overload isn’t considered; any awkwardness generated by the repetitive and unnatural language is overlooked; any anger towards the charity produced by the ignored donor requests goes unnoticed.

Considering primarily the needs of the charity leads to the dehumanisation of the donor: the image of an altruistic person gradually fades away and is replaced by that of a rational machine potentially dispensing money. This attitude creates a one-sided relationship: the donors do their best to cover the charity’s needs but their feelings are ignored.

The irony is that what’s best for the donor will inevitably be what’s good for the charity as well. If the fundraisers’ primary concern was to provide a great donor experience filled with positive emotions, they’d also achieve effortlessly what they now strive for: the charity’s goals.

Seven tips for a positive donor experience

- All communications should be compelling and inspiring supporting the feeling of ‘warm glow’ and happiness that comes with giving.

- Don’t stress the scale of the problem. Instead, emphasise the difference the supporter can make. This will set the positive feedback loop between happiness and giving into motion.

- Bring the issue to life with the use of emotions. Think carefully when and how you use factual and statistical information, as it can take away from the emotional experience and reduce responses.

- Eliciting empathy is imperative to helping behaviour. However, the intensity of feelings of pity and sadness should be manageable, or it’ll result in non-responsiveness and a sense of helplessness.

- Every interaction should leave the donor feeling better about their relationship with the charity. No donation should be based on guilt and people shouldn’t feel guilty if they don’t donate.

- Ask, listen and, more importantly, act upon your donor’s feelings towards and feedback about your interactions, and your organisation.

Citations:

1Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast & Slow. F. Straus and Giroux. New York.

2Damasio, A. (1994). Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York.

3https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1wup_K2WN0I

4SEO, M.-G., & BARRETT, L. F. (2007). BEING EMOTIONAL DURING DECISION MAKING—GOOD OR BAD? AN EMPIRICAL INVESTIGATION. Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management, 50(4), 923–940.

5Schkade, D. A., & Kahneman, D. (1998). Does living in California make people happy? A focusing illusion in judgments of life satisfaction. Psychological Science, 9, 340-346.

6Loewenstein, G., Prelec, D., & Shatto, C. (1998). Hot/cold intrapersonal empathy gaps and the under-prediction of curiosity. Unpublished manuscript, Carnegie-Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA.

7Ariely, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2006). The heat of the moment: The effect of sexual arousal on sexual decision making. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 19(2), 87-98.

8Bagozzi, R. P., & Moore, D. J. (1994). Public service advertisements: Emotions and empathy guide prosocial behavior. The Journal of Marketing, 56-70.

9Small, D. A., & Loewenstein, G. (2003). Helping a victim or helping the victim: Altruism and identi- fiabilty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 26, 5–16.

10Verkaik, David. 2015. “Making a difference as a helper: the effect of perceived prosocial impact and prosocial self image labeling on donations.” Unpublished MA thesis. University of Amsterdam.

11Zhou, X., Wildschut, T., Sedikides, C., Shi, K., & Feng, C. (2012). Nostalgia: The gift that keeps on giving. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(1), 39-50.

12Haynes, M., Thornton, J., & Jones, S. C. (2004). An exploratory study on the effect of positive (warmth appeal) and negative (guilt appeal) print imagery on donation behaviour in animal welfare.