Fundraising in the First World War: how the fundraising ground force made a difference

Few people could have predicted the scale of giving the inevitable groundswell of patriotic feeling during the First World War would inspire.

- Written by

- Tony Charalambides

- Added

- October 23, 2014

Asking someone in your immediate vicinity for monetary help is as elementary as fundraising gets. More often than not, it’s as effective as it gets too – which is why it pops up throughout history. From apostolic-era almsgiving, through nineteenth-century tin rattling, to face-to-face fundraising today, one person directly appealing to another for help works.

The First World War was no exception. It relied on the goodness of the charitably minded like no other conflict before (and, arguably, since) and grassroots appeals were an integral part of the picture.

This war cost Britain an estimated £3,251,000,000 from 1914-1918 (or about £320,000,000,000 in modern terms. That’s £320 billion/US$ 520 billion – a lot of money. Fundraising paid for a huge portion of that expense. And thanks to the efforts of ordinary people reaching out to their fellow man with a collecting pot or a keepsake to exchange for a donation, person-to-person fundraising (as we’ll call it) reached a new zenith.

It’s fair to say the ground was well-prepared for street collecting to attain new heights given the right national stimulus – which the First World War surely was. Collections had already made a huge impact on soldiers and their families fighting in the Boer War at the end of the nineteenth century. And a decade or so later – as Bluefrog founder Mark Phillips (@MarkyPhillips) has done an excellent job of reporting – campaigns like the one run on behalf of Manchester YMCA in 1912 (that all but consumed the city’s beneficent population) – signalled the arrival proper of ‘face-to-face’ fundraising from American shores.

Yet few could have predicted the scale of giving the inevitable groundswell of patriotic feeling would inspire. It’s reckoned £268,736 was raised through street collection for war-related charitable causes from 1916-17, a figure that climbed to £391,864 in 1918 and peaked at £416,640 as troops returned home during 1919 (multiply by 100 to get an approximate idea of how much that would be today). Clearly, face-to-face fundraising of this kind satisfied an appetite for public action that was burgeoning.

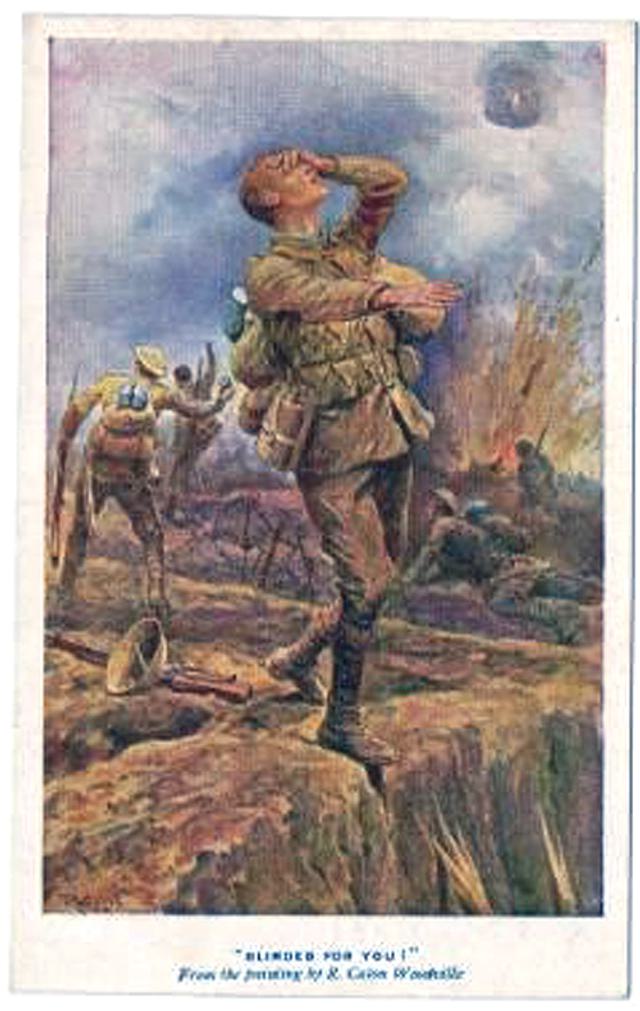

How was it achieved? One of the key tools was the humble fundraising postcard – replete with moving, often propagandist, images that inspired (and sometimes all but demanded) a donation. Thousands were bought and many were eminently collectible. Some of the most powerful – and effective – were produced on behalf of St Dunstan’s (since rebranded in 2012 as Blind Veterans UK), bearing stark images and – let’s be frank – shamelessly guilt-inducing messages like ‘BLINDED FOR YOU!’

One wonders if such a strong message would pass muster in today’s (arguably) milder fundraising and political climates (though, certainly, some armed forces charities are still using the tactic) – but perhaps that in itself is indicative of how the moral compass can shift in wartime, when extremes of action and emotion can make extremes of communication permissible too. Either way, the war’s estimated 18,000 relief organisations relied on potent postcards of this kind and – free to wield messaging that was as hard-hitting as they liked – the majority of them raised huge sums of money doing so.

But if postcard donations were a success, then flag days – that old fundraising staple that hit a high watermark in the 1980s but first came to prominence around the time the war began – were a revelation.

It’s been said that the first ever flag day was organised by Agnes Morrison, a Scot, who raised more than £25,000,000 (just over £2,000,000,000 today) before the war came to a close – and who is therefore credited with establishing the entire movement. In fact flag days had come into being around 1912 or even earlier, but there’s no disputing that Morrison and her subsequent imitators finally put the flag day on the map.

Her first such event took place on Saturday 5th September 1914 – with considerable numbers of fundraising foot soldiers to bolster proceedings. Three thousand six hundred collecting tins were issued and each volunteer collector (and no small number of Boy Scouts and Boys Brigades) carried a tray laden with tiny replica flags to be worn as badges – each costing just a penny – bearing images of soldiers, or slogans showing solidarity with, for example, prisoners of war, or the Union Jack itself. It was an immediate and unmitigated phenomenon: on the first day Mrs Morrison’s entire stock of Union Jacks sold out, and Mrs Morrison herself commented that it was a rare thing to encounter anyone not sporting a flag. It had ‘entirely captured the sympathy’ of the nation, she said. So much money was collected that it took 60 people two days to count it all.

When all was said and done, that first appeal raised £3,800 – roughly £380,000 today – and a major new force in fundraising, the flag day, had been launched into the public consciousness for good. True, the novelty began to wear off as the war progressed – countless causes jumped on the bandwagon and calls for regulation came thick and fast (they were answered as soon as 1915). The battle to stand out from an increasingly flooded market meant flags soon were replaced by lamps and miniature tanks and a bewildering number of other innovative alternative keepsakes.

But the idea of trading something of tangible, tactile value for much-needed funds was one that had natural traction the world over. In France fundraising badge days on behalf of soldiers permanently incapacitated by injury, or for refugees and orphans, were enormously successful too. And, of course, memento fundraising of this type was a direct ancestor of the enormously successful Marie Curie buttonhole, say, or the Royal Legion’s lapel poppy, to which we are all so accustomed today.

And for the First World War, at least, the support shown to soldiers out in the battlefields by anonymous fundraisers fighting the good fight on the streets of Britain – raising money so that they might eat, stay warm, enjoy some comforts and know, too, that their families were being looked after – was fundamental to keeping the fabric of the nation’s spirit intact when, otherwise, it seemed that so much else, including hundreds of thousands of young lives, was being lost.

© Tony Charalambides 2014

You can see many of the First World War fundraising postcards on Blind Veterans UK’s Pinterest page, where it has posted them to mark the centenary – from harrowing artists’ impressions of battles, to heart-warming family images and poems celebrating veterans themselves.

This article has been adapted from an earlier feature which appeared originally on Tony’s blog: www.tonycharalambides.com