George Smith: Working with suppliers, part one

It would be daft to write at length about fundraising creativity without taking a brisk look at the help you may need to exert the lessons of creativity in fundraising.

- Written by

- George Smith

- Added

- May 15, 2011

I must declare an interest. I have forever been an agency man. Though I have worked with hundreds of charities and cause groups in 20 or so countries round the world, my mode has always been that of supplier. In my sere and yellow years I remain just that: an agency hack. If you notice the occasional twinge of anguish in the next few pages, you can attribute it to 30-odd years before the agency mast.

For agencies, consultants and suppliers generally are often seen as parasites on the body of fundraising. Mythology has them growing rich and corpulent while the charity-wallah remains the soul of dutiful integrity, monkish or nunnish, penurious always. The supplier is the one in the Armani suit. The charity-wallah is the one in the anorak.

The facts deserve recall. Most senior British fundraisers these days earn quite as much money as their supplier counterparts. They also enjoy comparative job security. Agencies and consultancies wax and wane and tend to die early. Charities never die. Very few advertising agencies that were around in the 1960s still exist. All the charities do.

I will not elaborate the point. But there is still plenty of evidence that the imbalance of respect between charity client and charity supplier poisons many relationships that should be more fruitful. A client forever fearful that he or she is being ripped off is likely to remain wary of every aspect of the relationship. How can a test mailing cost so much? Who is really paying for all those lunches? How can their managing director afford that new BMW?

I’ll let you into a little secret. Suppliers, and especially agencies, are poor, quavering, fearful sets of individuals. Their financial performance is often abysmal by most standards of commerce and the individuals concerned are unlikely to be building private fortunes hence the occasional BMW when things look good. They live on hope – the place on a pitch list, the success of a presentation, the odd acceptance of a lunch date after a spot of networking. They work ferociously hard because they have to, because they are often the last ones down the line of production and distribution. They are in total, continuing and awestruck fear of all their clients every day of their lives.

It is this sad rabble that clients often think inhabit a world of wealth, power and esteem. The converse is true, at least in part. Clients have all the power – especially the financial power. Show me an agency with financial reserves as great as that of the average charity client and muse over the ethics of not paying the agency promptly.

But clients rarely use this power properly. In selecting a supplier, they often behave like coquettes, circling the sad rabble with dropped handkerchiefs and come hither body language. In using a supplier, they often appear bemused by the nature of the agency service. In dismissing a supplier, they often behave whimsically. When I have lost such clients in the past, it has often been at the peak of service performance but there seems to come a time when the apparent need for a new set of faces transcends any objective assessment of performance.

The rules of the game should be transparent.

- Decide what help you want.

- Decide who can help you.

- Vet the candidates.

- Choose one and give it the job.

- Let the organisation do the job.

- Allow it to work profitably.

- If it succeeds, say thank you.

- If it fails, fire it.

So, what help do you want?

It could be none, I know of charities where perfectly professional fundraising programmes are conducted from within the payroll. A printer or a mailing house may be occasionally needed but nothing more overwrought.

Most charities, though, need someone at some stage. It might be purely creative help, the ability to write and design a mailing pack, an ad, or a poster. If the need is occasional, the most cost-effective solution will probably be a one-person creative service or a consultancy. Always make sure, though, that the appointee knows about fundraising. Most creatives don’t. It is a specialist art.

As your needs grow either in terms of regularity or in terms of plurality you will begin to need a more formal commercial relationship. Advertising agencies beckon. You have a wide choice of rabbles.

If your programme has a heavy direct marketing component, you are wasting your time talking to anyone else but a direct marketing agency. Even here you could be wasting your time, for few direct marketing agencies know anything about fundraising. In Britain this gives you the choice of a couple of dozen reputable suppliers. It is quite enough to meet your needs.

Now, select. In Dear Friend, an American textbook on direct mail fundraising by Lautman and Goldstein (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, USA, second edition 2002) , a valuable chapter on choosing a supplier lists these six key questions to be answered.

1. Does our cause philosophically mesh with your firm?

There is no point in being silly about this. Agencies inevitably take on the characteristics of their proprietors and management, just as dogs start to look like their owners. Some will move in ‘progressive’ political circles and others will have a client list that better reflects captains of industry and the like. A cancer charity is unlikely to be relaxed with an agency that works for a tobacco firm.

My own agency would never have taken on the Conservative Party and wouldn’t have been asked. Comfort is a mutual process.

2. How do you charge?

Which is probably the key question because clients seem either uninterested in the subject, or dazzled by the nuances of agency remuneration. Like is rarely compared with like in this field.

It should be easy to say how much it costs to produce a mailing pack. It should be, but it isn’t. How can you quantify five sets of revisions and author’s corrections at every stage of setting? How much should you pay if the work stinks? This is so often the friction field of an agency/client relationship. Mutual respect and understanding can ease the pain but it still should mean a more formal agreement on who pays as work changes.

If the work is continuous, if the work demands a true and regular partnership, if you need the strategy of the process as much as the execution, then the agency should be receiving a basic annual fee. This in itself will give them a cushion against which to bounce the inevitable accidents of approval and disapproval. But it also gives them a feeling or commitment, the sense that they are senior partners in your fundraising programme and not just occasional contributors to it. I would not these days agree to offer a full agency service to any client who wavered at the thought of a basic retainer.

For the client runs a considerable risk in denying such a relationship. Most agencies still make most of their money on commissions and mark-ups. In other words, the more they can persuade the client to spend, the more money they make. This can be dangerous, very dangerous, in fundraising. A good agency should often persuade the client not to spend money and they should not feel financially challenged when they offer such ideological largesse.

But there will always be commissions and mark-ups and they should be clarified in advance. Should the agency hang on to all its advertising commissions or should it pass on a percentage? What will be the precise mark-up on production work controlled by the agency? All these things should be clarified in advance and all of them should be contractual between the two parties. What’s in the basic fee and what’s not? How many agency hours are predicted to mount a campaign? Who pays travel costs?

Both parties need a menu of explicit financial agreement, the tighter the better. And both parties need regular budgetary control as the relationship matures lest things get too sloppy. Burnett Associates used to send out dozens of estimates a week, often for dumb things like 2,000 envelopes. It is doubtless tiresome but it is good discipline and proper courtesy.

The potential client should always be prurient in advance about the supplier’s charging practices. The potential agency should always be totally candid in the face of the prurience.

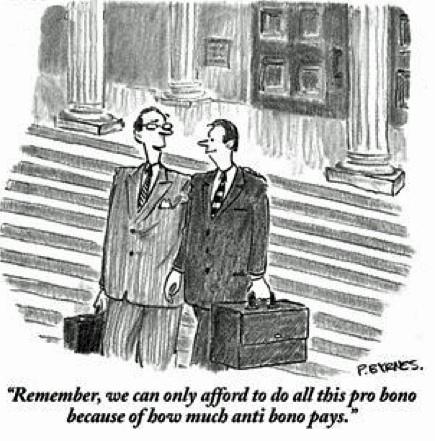

One last observation on charging by suppliers: if the supplier offers to work for nothing, look for the exit sign. Suppliers are not part of the voluntary sector in this sense. A promise of free creative work in particular should have you studying the production bills with great care. Pro bonoare two very deceptive words.

3. Who are your clients?

No problems here, for the supplier is going to bend your ear with their names anyway. But, why not take it a stage further? Ask for permission to approach those clients direct and ask supplementary questions: what’s good, what’s bad, what’s brilliant, what’s insufferable? Always tell the supplier if you intend to do this. It is good manners.

4. How long have you been in business?

This is probably more important in the United States than it is here, for they worship more fully at the shrine of corporate longevity. But if a supplier has been around for a few years, it does indicate a certain professional stability and a certain greater experience. Remember though, that good people are breaking away from older suppliers all the time to start their own businesses. Don’t dismiss them because they are corporately junior. When Maurice Saatchi started a second agency it was technically a newcomer but you’d have had a reasonable expectation of professionalism.

5. Who will work on my campaign?

Much more important, this. Famously, agency presentations are headed up by high-profile proprietors who melt away after the pitch to be replaced by unknown nerds. There is no need for this in the size of supplier company that is relevant in fundraising. Always feel free to ask these questions explicitly. Who will write for you? Who will be the art director? Who will manage your business? It is the client’s right not just to ask such questions but to demand some time with members of the putative account team. They are going to have to work closely with the client and there is nothing self-conscious about interviewing them accordingly.

6. May I see samples of your work?

Again, no problem – the supplier is probably willing to bang on about previous work until the pubs open. Know, however, that what you will hear will always be success stories. Make a nuisance of yourself. Tell them – but tell them in advance – that you want to hear about some failures as well.

Failures are often as indicative as successes – we all have them and we would all benefit more if we shared them.

Notes

© 2011 The White Lion Press Limited

This article is reprinted with the author’s permission from Asking Properly, the art of creative fundraising by George Smith, available from the White Lion Press Limited (http://www.whitelionpress.com) price £24.00 plus p&p.