Howard Luck Gossage – the ‘mad man’ who changed the world

When you think of advertising’s greats the faces of David Ogilvy, Bill Bernbach and Leo Burnett gaze imperiously from the industry’s Mount Rushmore. Few can doubt their right to be there. For example, Christiana Stergiou’s appraisal of David Ogilvy’s career for The Great and Good was appropriately titled: ‘The father of advertising’.

- Written by

- Steve Harrison

- Added

- June 16, 2013

But now I’d like to add another face to that tableau. One, however, that few of you will recognise.

It belongs to Howard Luck Gossage.

If you’re response is ‘Howard who?’ then I’m not surprised. His agency was based in an advertising backwater, San Francisco, in the late 1950s and sixties; he never did a TV commercial in his life; and he turned down or resigned business in order to keep the number of staff to below 13.

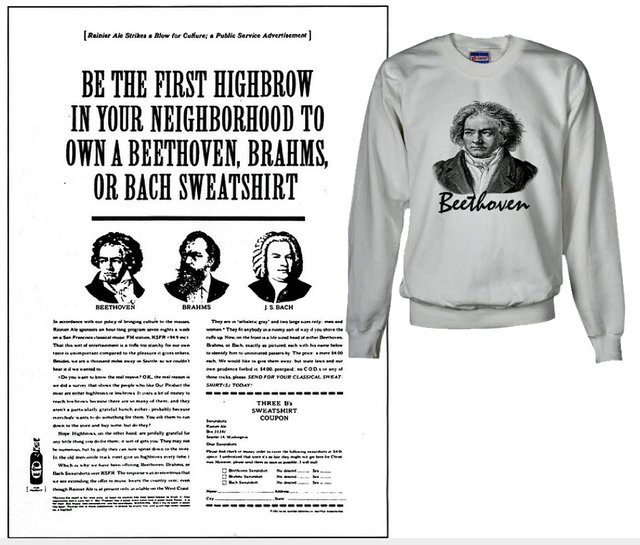

At the time, many of his peers regarded him as a scoundrel. In fact, Business Week reported that his name was ‘anathema to his rivals’. When he was dying from leukaemia in July 1969, he lamented that: ‘I’ve never done anything that means anything to anyone in this world except maybe invent the Beethoven sweatshirt.’ One can assume that this last claim to fame provided little by way of consolation.

View original image

View original image

Yet HLG, as he was known, was a natural and consummate fundraiser, the first person to use the term ‘interactive’, to have conversations rather than ‘talking at’. He wrote some of the quirkiest and most effective ads of all time, in the process breaking all the rules. He helped launch the environmental movement and left a legacy of brilliant communication campaigns, which for the first time showed that advertising isn’t just about selling a product, it can be used to change the world.

After his death, there was a respectful obituary in Advertising Age but, basically, that was it and within a handful of years Gossage was forgotten. As Jeff Goodby, the founder of Goodby Silverstein and Partners told me, ‘In the early eighties no one knew about Gossage. It was strange. There was a gap in everybody’s memory.’

It’s not so strange really. Like its contemporary counterpart, the Maoist Cultural Revolution that sought to erase vast tracts of Chinese history, the Creative Revolution that transformed the US ad industry in the 1960s had its own unchallengeable leader, Chairman Bill Bernbach, and a similar scorn for the past.

With a self-assured ignorance that remains uncorrected to this day, young creatives figured they had nothing to learn from anyone but Bernbach. Their elders stayed silent and followed fashion for fear of being denounced as reactionary or, that most unforgivable sin in the advertising business, old.

Thankfully Jeff Goodby, fellow copywriter Andy Berlin and art director Rich Silverstein were willing to think beyond the new orthodoxy. These three young admen discovered Howard Gossage in the early 1980s and began a life-long love affair with the Gossage way of doing things. Indeed, when Goodby, Berlin and Silverstein set up their own agency in 1983 they launched with a headline that paid tribute to their mentor, ‘Introducing a new agency founded by a guy who died 14 years ago.’ Nearly 30 years later and Rich Silverstein is still clear about the agency’s inspiration, ‘Is it true that Gossage was the reason we founded our company? Yes.’

View original image

View original image

Meanwhile, Gossage’s admirers in Europe were keeping the faith. Barrows Mussey, an American living in Germany, had already published an omnibus of Gossage’s speeches: Ist dir Werbung noch zu retten? (Can advertising be saved?) And, under his wife Dagmar’s determined supervision, this was finally published in 1986 for an English-speaking audience as Is there any hope for advertising? (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, USA, 1986.)

The torch was taken up in 1995 by Bruce Bendinger when he published his homage, The Book of Gossage (reissued by the Copy Workshop, USA, in 1995). Those who have read it are left in no doubt that the man’s legacy was far richer than that of the other advertising greats whose fame eclipsed his in the fifties, sixties and the years thereafter.

Would Gossage have enjoyed the comparison? Probably not; because, while he liked Ogilvy and respected Bernbach, he had little interest in his peers and even less respect for the industry in which they all worked. Given his disdain, it is tempting to think of Gossage as a brilliant man who just happened to be in advertising. But to do so would be to ignore a truth that would probably have annoyed the hell out of him: he was a marketing genius with a gift for writing great ads.

As that modern industry star Alex Bogusky says, ‘You really can’t overstate the influence of Gossage on the early Crispin Porter + Bogusky work. At one point every new recruit was given a copy ofThe Book of Gossage... to the core group it was a touchstone. As our work began to move online we used to sit around and wonder, “what would Gossage do?” WWGD? We almost felt a responsibility to be interactive in the shadow of Howard.’

Rory Sutherland, a long-term devotee and now vice-chairman of OgilvyOne puts him in context: ‘Gossage is the Velvet Underground to Ogilvy’s Beatles and Bernbach’s Stones. Never a household name but, to the cognoscenti, a lot more inspirational and influential.’ The king of the Gossage cognoscenti, Jeff Goodby, agrees, ‘The best of Gossage is the best advertising ever done.’

View original image

View original image

An overstatement? Well, in his book The Real Mad Men, Andrew Cracknell tries to get the reader to appreciate the brilliance of Bill Bernbach’s output. But, however outrageous running an advertisement with a headline that spelt BARGAINS backwards might have been in the 1950s, it comes across as a ‘you had to be there’ moment to today’s audience.

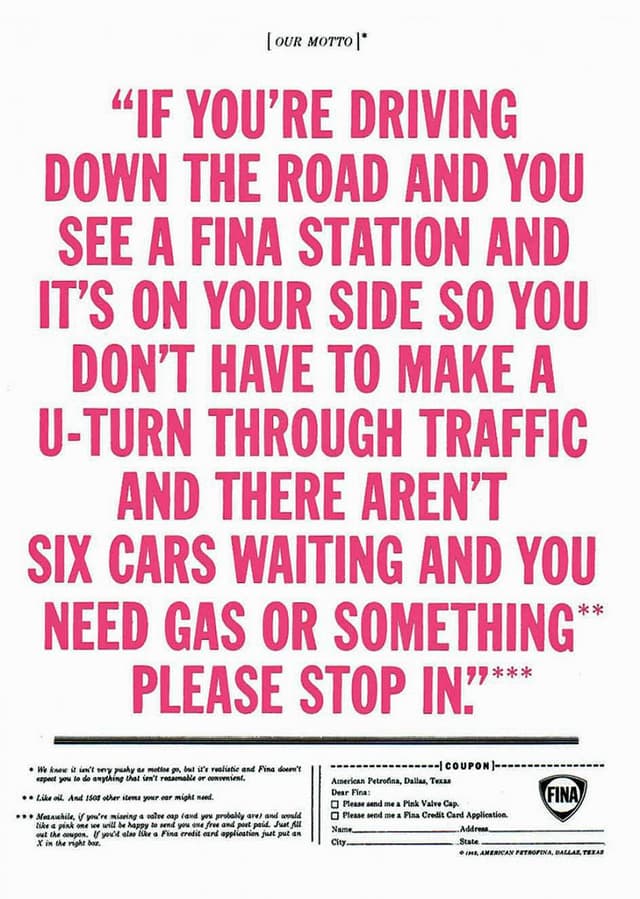

Gossage’s long copy headline for Fina the petroleum company, however, would be outstanding if it ran in tomorrow morning’s papers. For who today would have the audacity to write something as arrestingly honest and endearing as: ‘If you’re driving down the road and you see a Fina station and it’s on your side so you don’t have to make a U-turn though traffic and there aren’t six cars waiting and you need gas or something please stop in.’

View original image

View original image

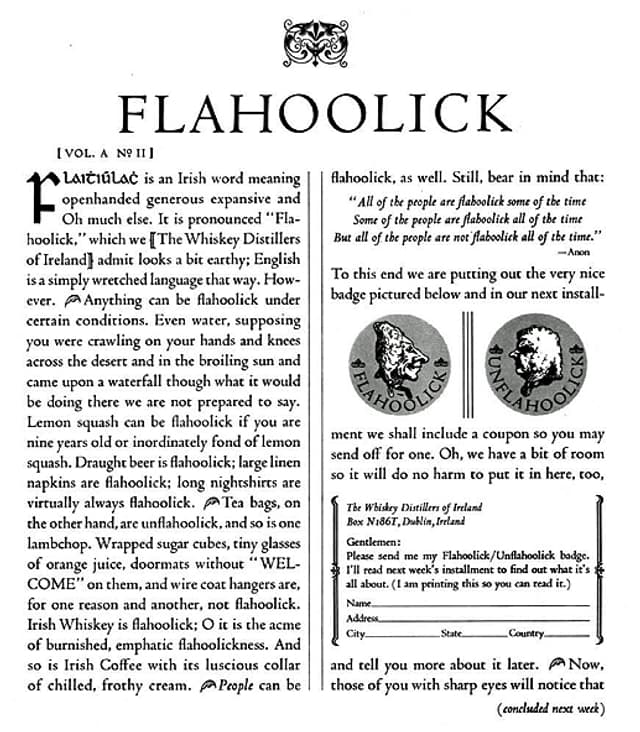

In this and other campaigns, he created a new style of advertising that he called ‘interactive’ some 40 years before anyone coined that term for digital communications. He then used his interactive style to get people to opt in, create communities and converse with the brands he was advertising.

As Jeff Goodby says, ‘He foretold what’s happening in the Internet and social media.’ That alone should be sufficient to win him universal respect. But the ads were just one aspect of his brilliance.

He was also the first adman to recognise the potential in integrating PR into his communications plan. Indeed, the ads he wrote were usually just the starting point for a campaign message that would then be amplified by the press, television and radio, and any number of different media. Suffice to say, 50 years later, all today’s big PR-generating campaigns that are lionised at the Cannes Advertising Festival for their ground-breaking brilliance can be traced to what Gossage called his ‘ad platform technique’.

Other innovations of Gossage also had to wait decades to find success. The Kick-Back Corporation (the first media-only agency), Generalists, Inc, (which pioneered what we now call behavioural economics) and pay reading (which comes to us today as pay-per-view) were all big marketing ideas that singly should have guaranteed lasting recognition. Taken together, they’re evidence of marketing genius.

View original image

View original image

It is true that he would not have liked that conclusion. He preferred the company of more esoteric thinkers; and looked for the kind of cause that he felt more worthy of his talent and intellect. Indeed it is the worthy causes – and the way that he used his talents to promote them – that really set him apart from the other greats of his generation.

One of those greats, David Ogilvy, described Gossage as, ‘The most articulate rebel in the advertising business.’ And explained his old friend’s view that ‘Advertising was too valuable an instrument to waste on commercial products… it justifies itself only when it is used for social purposes.’

According to Gossage’s colleague Jerry Mander, ‘He believed it was possible to use advertising to create issues and cause discussions [and] he would do it with one insertion and a few dollars, and cause big things to happen. He invented that format, that style, that way of speaking and that kind of shocking way of presenting things so that it really broke through.... His advertisements and the ones we did together were highly efficient in that they were actually able to break out a subject or a point of view that had, up until then, not been discussed enough in public. He was an iconoclast. He said he liked to throw a pebble in the water and see the ripples.’

View original image

View original image

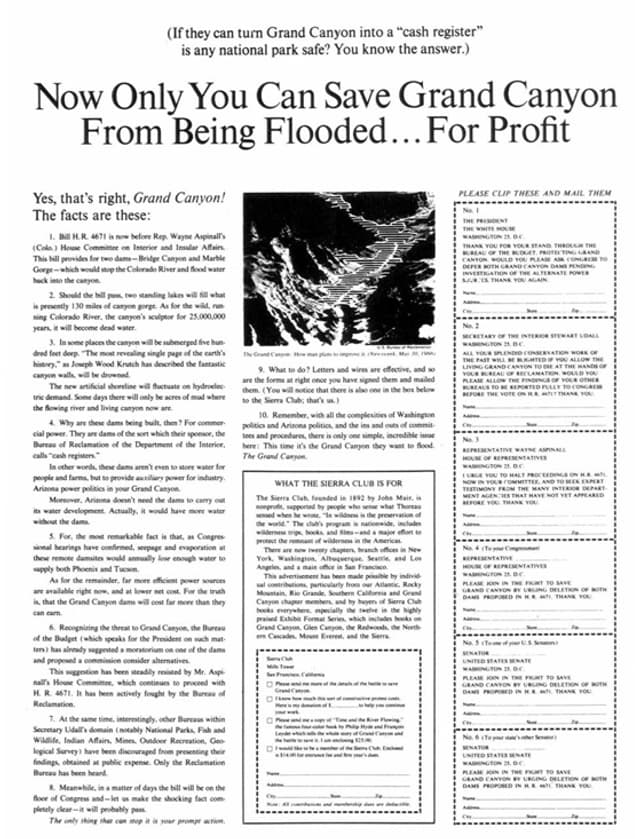

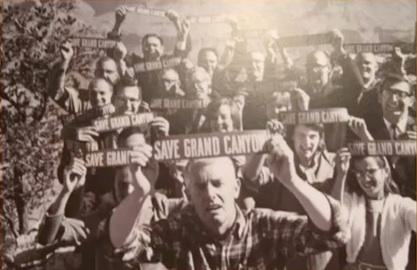

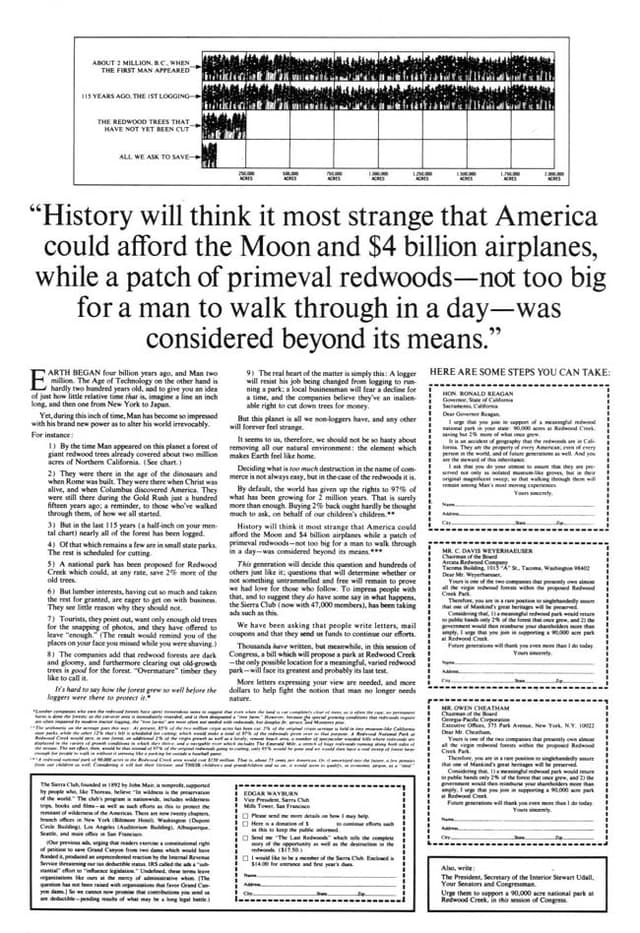

The first big pebble he threw came in June 1966 when the Gossage agency began working with the Sierra Club’s David Brower on a campaign to halt the damming of the Grand Canyon. Not only did those ads succeed, they also kick-started what we know today as the environmental movement. As David Brower’ son Kenneth explains: ‘The ads brought a lot of activist people in. This really was the first time that Americans had confronted government in this way and I think the ads were crucial.’The Grand Canyon victory was just the first in a series of headline-making successes and, by the end of the decade, Gossage and David Brower had transformed what had been the US equivalent of a local Rambler’s Association into a nationwide organisation with real political clout.But that wasn’t enough for David Brower, for he’d decided that a global vision was needed. And, having left the Sierra Club, he took his idea to Howard Gossage. The adman gave this new organisation a name – Friends of the Earth – and a base in his agency. In fact, from the two rooms that Gossage supplied rent free, Friends of the Earth has become the world’s largest grass-roots environmental organisation with 5,000 local activist groups and the combined number of members and supporters is over two million.

As I said at the beginning, you may not have heard of Howard Gossage. But you have heard of Friends of the Earth and, if you’re involved in fundraising, you will no doubt have used many of the advocacy advertising ideas that he pioneered.

Those ideas are still as fresh and potent today as they were when Gossage was cooking them up in his tiny office upstairs at his bijou agency in a none-too-salubrious neighbourhood of San Francisco.

And not only have his ads and ideas stood the test of time better than those of his more famous counterparts, his aphorisms are also more memorable. For did David Ogilvy, Bill Bernbach or Leo Burnett ever say anything as pertinent or challenging to future generations as Gossage’s off-hand remark that ‘Changing the world is the only fit work for a grown man’?