Secrets of direct mail 2: answering the right questions with your envelope

Good practice in direct mail fundraising starts with the envelopes. In part two of our series looking at Siegfried Vögele’s direct mail approach, Chris Keating explains how.

- Written by

- Chris Keating

- Added

- June 10, 2019

Much good practice in direct mail was first described in the late 1980s in Prof Siegfried Vögele’s seminal book Handbook of Direct Mail. I’ve crafted this series of posts to share his insights. Check out the first post, which is all about the approach!

This article first appeared on Chris' Medium blog here.

Imagine you’ve picked up an envelope from your doormat. Odds are, the first thing you do is look at the address on it, to check it’s meant for you. Once you’ve done that, you’ll very quickly look at it to work out what it’s about.

According to Siegfried Vögele, the following questions are likely to be running through your mind.

- What do they want from me?

- What benefit is there in it for me?

- Do I need it?

- Is it for me?

Within about eight seconds of picking up the envelope, you’ll decide whether to open it or throw it away — or possibly, put it to one side to open later.

If your job is creating direct mail to generate leads, sales, donations or change of any kind, then you want your letters to be read — and for the recipient to then act on the contents. Read on to hear what Siegfried Vögele has to say that will help you! A caveat: Exactly what approach works for you, your cause/product and your audience is a question that can only really be answered by testing. Any theory can only suggest approaches you MIGHT take. If in doubt, send half your audience one version and half your audience the other on the same day, and see what happens!

The ‘original letter’.

A real letter from a real person is what Vögele terms an original letter. An original letter has a plain, normal-sized envelope and regular postage. It’s clearly addressed to the individual, from an actual person, who has good reason to write. Original letters range from an emotional note from long-lost great-aunt to a boring but possibly important letter from your doctor or insurance company. Inside an original letter you expect to find few, or no, enclosures.

An ’original letter’, or something that looks like one, is very likely to be picked up off the mat and opened.

The opposite of an original letter is advertising. A coloured, designed envelope with photos or copy implies that the communication is mainly selling something. It might be clear from the address that there’s some kind of personally-addressed letter inside — and it’s great if there is ! — but the recipient now expects that there will be some kind of request for time or money inside.

No, not everything should come in a plain white envelope.

A common mistake about the dialogue method is thinking everything should look like an original letter in a plain envelope.

Plain envelopes make a promise to the reader that the contents are personal, timely and relevant. If this turns out to be right, that’s a big amplifier. But if it’s wrong, it’s a big filter.

If someone opens a plain envelope to find a personally-addressed letter and a small number of enclosures, they say a small ‘yes’. Their guess that this was a real letter has been proved right. This is an amplifier. All the better if the letter is from an organisation or even a person that the reader actually knows.

By contrast, if someone opens a plain envelope to find a leaflet, or a letter addressed ‘Dear Homeowner,’ or just about something totally irrelevant — their guess is proved wrong and they say a small ‘no’. They’re less likely to respond positively!

So before you go down the ‘plain envelope’ route for a direct mail communication, you need to be very sure that what you’re writing about justifies it. Did the recipient ask you to write? Are they expecting something? Are you on the list of organisations they actually are interested to hear from?

The blue ink letter.

The best example of the ‘original letter’ approach I know is from politics. (Apologies for the digression from Siegfried Vögele, who doesn’t mention politics at all, but it’s an instructive example.)

In close election campaigns, the UK’s Liberal Democrat party often sends letters to voters that look handwritten, on light blue paper, in light blue envelopes that have actually been addressed by hand. These are usually timed to land on doormats two to four days before the election.

Does this work? Surely, no one thinks a politician is a real person with a real reason to write to them?

In fact these can be very effective— but it depends on both content and context. It works when the campaign has created the impression that the candidate as a champion of the local community, as much as their actual politics. Then the letter inside the envelope is written in the tone of a neighbour writing to someone who lives down their street, not the tone of a politician pitching for votes. By doing these things the Liberal Democrats gain acceptance that these communications are real letters from real people, not a cynical marketing ploy by desperate politicians.

Effective ‘advertising’ envelopes.

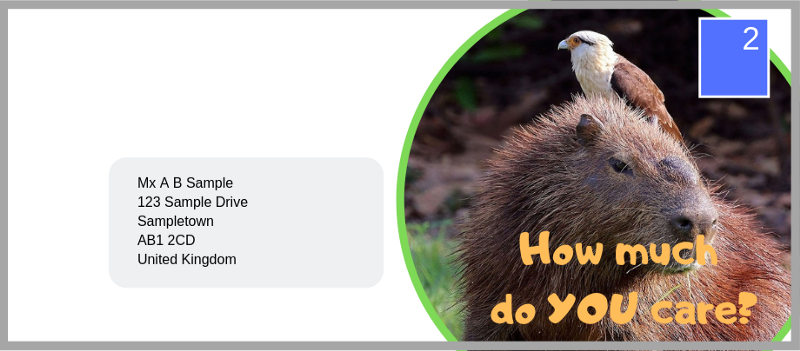

If the envelope isn’t plain, then the objective of the envelope is to make it clear why the reader should care about the contents. What’s inside, and do they want to engage with it?

If you’re writing to appeal for vital funds to save the capybara, you might as well have photos of cute capybara on the outside of the envelope, so your audience of capybara lovers go, ’Yes, capybara! I know what’s inside!’ and then feel a glow of satisfaction when they find your capybara-related material inside. This gives your audience good answers to their unspoken questions. Not only have they correctly guessed it’s advertising (yes!) they have correctly guessed it’s something they might be interested in! (Of course, this assumes that what you’re writing about is actually interesting to your audience. But if you’re not, there is almost nothing you can do that will make your campaign a success.)

It’s certainly possible to create lavish envelopes with strong photos and bold copy. But you don’t necessarily need to do this. Even a relatively light-touch cue can give someone a lot of information about the contents of the envelope, and answer their unspoken questions.

Envelope size and postage.

People also use the size of an envelope and the postage on it as a clue to the contents. When Siegfried Vögele was writing in the 1980s, he found that a C6 envelope (one quarter A4) looked personal, a DL envelope (one third A4) looked personal or commercial, a C5 envelope (half A4) was almost always seen as commercial and a larger or irregularly sized envelope inevitably looked like advertising, even if the envelope was plain.

The main takeaway from this is that if you’re going down the original letter, keep-it-simple, route, then you’re best placed to stick with the kind of envelopes that are used for actual letters – DL or C6, maybe C5.

Postage also gives some clue as to the contents. The most ’original’ kind of postage is of course stamps. Vögele found that stamps on a letter from an individual or small business looked more individual, but letters that were from a large company didn’t seem any more personal because a stamp was added. A franked or mail-sorted envelope (mass mail with pre-printed imprint from the mail deliverer) suggests that it’s some kind of commercial or official correspondence, though it might still count as an original letter.

That’s pretty much all Siegfried Vögele said about envelopes. However, re-reading the Handbook of Direct Mail prompted many thoughts, and I’ll discuss them in the rest of this post.

Is a plain envelope even possible?

It’s very difficult to have any mass direct mail with a properly plain envelope. You’re likely to have a return address and registered company/charity details, probably on the envelope flap. You will very probably end up with your logo and possibly the logo of a regulator or trade body as well.

That is enough to give the audience plenty of clues about who the letter is from. And if they have an answer to ‘Who’s this from?’ they can probably make an informed guess about ’What’s this about?’ After all, most letters from most organisations are pretty consistent. Hotel Chocolat is unlikely to be asking for donations, the Capybara Club is unlikely to be enclosing tax details, and the Tax Office is unlikely to be giving me ten per cent off my next chocolate order.

If your audience knows who you are, or is expecting a letter, or has found previous letters interesting, the recipient’s expectations will act as an amplifier. If you’re not confident about those things, then you probably need to take particular care to highlight the benefits of opening your envelope — that is to say, what the recipient will gain from ultimately acting on the call to action inside.

Should we ask for money / indicate the price on the envelope?

Working in fundraising, I’ve often heard people suggest that we should ask directly for money on the envelope. ‘Your gift today will save the capybara!’ Often, I’ve heard this from people whose background is in major donor fundraising, who are trained to always be very clear and upfront in ‘making the ask’. However, think back to the principles of the dialogue method.

How many salespeople open the door and say, ‘Hi, I’m Chris, and I’m here to ask you for £10 a month for the capybara?’ Not very many! Usually the mention of money and how much comes some time into the conversation — at the end, or at least the beginning of the end, after the potential donor or customer has said ‘yes’ to smaller questions. If the recipient is asking themselves, ’How much is it? Can I afford it this month?’ then you have already overcome questions like ‘Do I need this?’ or ‘Who will this donation help?’

The dialogue method suggests the right thing to do is to focus on the benefits of giving, not on the price or amount you are asking for. Why then do some very successful major donor fundraisers get this wrong when it comes to direct mail?

If a major donor fundraiser is ‘making the ask’ to a wealthy individual, then much of the conversation has already happened. There have already been meetings, calls and letters that have established the person concerned is interested in the cause and what in particular they might wish to fund. And they have already agreed to the appointment with the lady or gentleman from the development office, knowing full well that they are going to be asked for money.

We direct mail fundraisers have to cover much of that same ground in the twenty seconds it takes for someone to decide whether or not to read a letter, with perhaps ten thousand people at a time.

When might it be a good idea to ask for money on the outside of the envelope?

Of course sometimes a prospective donor is already expecting to be asked for money. If they’re a member of your organisation, and they know their membership will be up for renewal. Or perhaps if they’re used to getting your emergency appeals and they’ve seen and heard about another disaster through the media.

What role does intrigue have?

I often hear people talk about using intrigue and suspense as a method of getting the envelope opened.

After all, most direct mail is boring. So surely it’s a great idea to grab your reader’s interest by putting text on the envelope text saying, ‘What secrets lie in this envelope?’ or, ‘What has no legs in the morning, four legs at lunchtime and four legs in the evening?’*

Siegfried Vögele doesn’t deal with this directly, but his method is about answering questions, not about creating them.

Your reader already has questions like, ‘What’s this about?’ on their mind. They don’t need even more questions and they definitely don’t need confusing answers to the questions they already have!

Going back to the face-to-face sales analogy — how often does a salesperson open a conversation with, ‘Hi, my name’s Chris, would you like to see inside my mystery box?’ Not very often!**

The dialogue method suggests that a ’teaser’ envelope will work best when the ’tease’ is so obvious that it’s actually selling benefits of reading the letter and responding.

If you judge your ‘teaser’ copy or question correctly, then it will help answer questions such as, ‘What’s this about’ and, ‘Am I interested?’, even if obliquely. After all, if I can see an envelope is from a charity I support, I probably know it’s probably asking for money. If it’s from a chocolate company, it’s probably selling me chocolate. Reinforcing that guess and suggesting an interesting answer will act as an amplifier.

If your envelope doesn’t get opened, your letter will never be read and no-one will respond. So the eight seconds it takes for someone to decide to open the envelope are important!

An ‘original letter’ in a plain envelope with no signs of being a marketing communication is likely to be read and opened. But don’t create false promise — it may be better to use your envelope to give clear and enticing answers to questions like ‘What’s inside?’ and ‘Am I interested in this?’

Thank you for reading this far! You can find the first post in this series about the dialogue method here. And next time: the letter itself and how people read it.

Footnotes

*Answer: A capybara

** Actually, I’ve seen this done once — at a gaming convention where it was obvious there was some kind of game inside the mystery box!

This series of articles first appeared here.

© Chris Keating 2019. Reproduced with permission.