Anatomy of the Wishing Well Appeal. Part 2.

- Written by

- Marion Allford

- Added

- January 18, 2010

Reflections on a strikingly successful appeal

MARION ALLFORD LOOKS BACK – 20 YEARS AFTER

I have often been asked why the Wishing Well Appeal achieved such a wide response. I believe it was due to the deep affection many people feel for Great Ormond Street Children's Hospital; and the detailed planning and sophisticated marketing techniques used to communicate the fact that the hospital was in trouble. We needed the public to know that, without their active help with fundraising, the hospital's future could have been in jeopardy.

Great Ormond Street has a special effect on all those who come into contact with it. Remarkable achievements and human tragedies are almost daily occurrences. Parents feel great anxiety when their child is ill enough to be referred there, yet relief to know they will receive the best possible medical and nursing care. Apart from the dedicated doctors, nurses and administrators, they are supported by other parents, by volunteers, social workers, teachers and chaplains, all trying to lighten their load and to sustain them at a critical time for any family.

But emotive causes do not always raise all the money they need. So, because we could not afford to fail, we used every opportunity and technique at our disposal to ensure success, which meant patience and detailed planning to develop a four-year programme. And the response we received – not only in funds, but in approval for the strategy used – more than justified the careful approach we adopted.

It is a well-known statistic that, with most one-off appeals, about 80 per cent of the funds usually come from 10 per cent of the donors. Great Ormond Street with its wide popular appeal had an unusual result. It received 40 per of the funds it required from those giving or raising amounts of less than £1,000.

To have been part of the Wishing Well team was a great privilege. And to be there from start to finish was particularly exciting and rewarding.

For the staff and many of the volunteers, it was a seven-day a week job. We planned the appeal, set up the structure and achieved some lead gifts then ran the private appeal (approaching potential major donors, donor to donor, on a personal basis). Once we had raised or had received pledges for at least half the funds (we would have sought more if it was not such an emotive cause), the plan was to go public and to have a mega press event to launch it and then a drip feed of major special events to keep the appeal in the public eye.

But it was not easy to convince top business leaders to hold back. One of the most difficult issues was when a national newspaper wanted to hold a £1m appeal for the hospital (not the redevelopment appeal) the Christmas before we planned to go public. We explained that it would 'leak' the story a year ahead of the launch and, therefore, put at risk the high impact launch we planned. We were not at all popular for turning down such a large sum. It was only a year later, when everyone saw the complete blanket coverage we achieved for our launch, that the reason for the decision was fully appreciated.

Astounding moments

There were two particularly astounding moments I remember. One was when, seated at my desk, I opened an envelope that enclosed a cheque, which appeared to be for £1m. But on closer inspection, I saw that it was for £3m. I nearly fell off my chair as we had had no warning that this member of the commerce and industry panel was going to give such a gift.

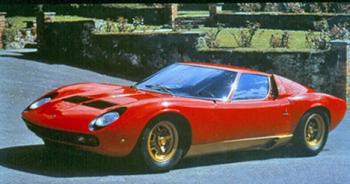

The other incredible instance was when I received a call from Geneva, from someone who said that Great Ormond Street had saved his child's life and he was ready to give back now. He said he would give us two Lamborghinis and run a vintage car auction with Christie's, held at Brocket Hall (an English stately home, now a sports club). I must admit, it took me some time to realise that this offer was genuine! The event raised £1.5m for the appeal and he and a friend bought back one of his Lamborghinis to help to swell the coffers.

What’s new in fundraising?

It is amusing to see how each generation believes it has many new and innovative ideas when fundraising. We also thought that our plans were fairly innovative, only to discover in the hospital's archives that many of the same methods had been used in an appeal made in the 1930s. This included asking donors to 'name a brick', to name areas in the hospital, and much more.

However, there were some particular strategies we used which were seen as unusual or innovative at the time. Several of these are described below, as they could be useful to other appeals.

Attracting statutory funds

Major donors always like to know that a charity has exhausted all possible statutory funding before it looks to philanthropic contributions.

When I joined Great Ormond Street I was told not to bother to pursue statutory funding because the hospital had just had a large injection of funding from that source for the cardiac block. Nevertheless, I felt we should at least be seen to have tried. Hence, with the architects, we split the attractive options on the needs list from the less attractive, with the intention of asking Jim Prior (now Lord Prior) to ask the government to contribute 50 per cent of the costs. He did this before he had confirmed he would chair the appeal. It was a great day when we heard that the government had agreed to fund half the costs and to let the appeal fund the second tranche to give us time to raise the money. In the end, the appeal's target was £42m against the government's contribution of £30m, because our half attracted considerable inflation (this was a time of high inflation in the UK, so during the years of the campaign, the value of money fell noticeably).

I think this proves that a fundraiser should allow a potential donor to say no for themselves, rather than assume a negative response.

Choosing an appeal name

Long, complicated names will not do for public appeals. But it is not easy to find something different and imaginative. During the private appeal stage of the Wishing Well Appeal, we continued to use the long but descriptive name – the Great Ormond Street Children's Hospital Redevelopment Appeal, whilst we wracked our brains for something short and catchy.

If we could have called it the Great Ormond Street Appeal it would have been simple and would have underlined the brand of the hospital. But, as the hospital needed to receive general funds at the same time, we had to invent something different.

The name came to me when I was looking at the story boards for a joint promotion with Harrods, the well-known London department store. The idea was that people would throw money into a wishing well for the hospital. My colleague wondered what was wrong with me when I shouted, 'that's it!' And so the name was born. The funny thing is that, when I asked the archivist if the hospital ever had a link to a wishing well, he found that there had been one in the garden of the original site of the hospital (see photo opposite).

However, as a new identity, the appeal name needed a lot of support publicity to be sure that it became closely associated with the hospital and its redevelopment.

Developing a logo

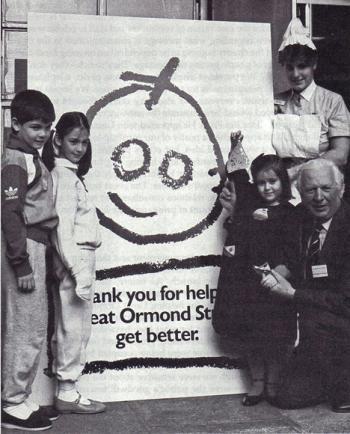

One of the most important aspects of the Wishing Well Appeal was its logo. An effective logo needs to have clean lines and an easy to recognise image. It needs to be clear enough to identify when it is reproduced onto a pencil, for example.

The drawing of a child's face (see opposite) with a tear descending from one eye has an appealing charm and provided an ideal visual focal point for the fundraising campaign.

It was designed by the appeal's honorary advertising agency. They also developed the effective, 'call to action' slogan – Help Great Ormond Street get better – which appears beneath the logo. 'For the final press conference, which announced the completion of the appeal, a photograph had to be produced which told the story in a 'nutshell'. We sifted through many ideas, before deciding on the photo opportunity opposite – the appeal chair, Lord Prior, and eight-year-old Laura peeling off the tear from the appeal logo, to symbolise the end of worrying about the hospital's future. Of course, the tear went back on soon after the conference and has remained there ever since as it is such a valuable logo, which had immense visibility during the appeal and, indeed, ever since.

Persuading your patrons to come on board

There are so many charitable appeals, how can you persuade influential people to link their special name with your endeavour? The answer is to do your homework to make sure that your approach and request are very well explained, giving reasons as to why they, in particular, are right for the cause.

When I joined Great Ormond Street, the hospital wanted to ask The Princess of Wales to be the Royal Patron of the appeal. My reasoning was that we also needed The Prince of Wales, because sick children at the hospital needed both parents, not just their mother. Charities usually have just one main royal patron and so this was an out of the ordinary request.

To help to make an irresistible approach to the Palace, we consulted the hospital's archivist, who showed us a long and detailed history of all the Royals who had supported the hospital, going back to 1852 when Queen Victoria became the first Royal Patron. From this we had a special, leather bound, gold embossed, sponsored book produced, which underlined this proud tradition. It even showed that, in the early 1900s, The Prince and Princess of Wales of the day attended a charity fair for the hospital to help fund a new boiler (one of the less attractive items we were now asking the NHS to pay for!). The hospital was delighted when the Royal couple accepted the invitation. They attended many events throughout the appeal and made a major contribution towards the appeal's success.

Saving on staff time, attending cheques presentations

Once the appeal went public, the staff were inundated with requests to go to different parts of the country – to clubs, pubs, businesses, etc – to collect cheques for the money which had been raised. There were simply not enough people available. So we devised a system that helped us with such a nice problem and also added to the fun for the volunteer fundraisers. We invited them to visit the hospital to present their cheques to a well-known person, or celebrity. We had a long list of celebrities who had offered to help with this plan. These events were called Cheque Clinics and several cheques were handed over in this very up-beat way, helping to bring our volunteer fundraisers closer to the hospital, as well as showing the hospital's gratitude.

A strategy for spreading a convincing call to action

Obviously, using the media is the recognised method of spreading the word about your cause. But what about convincing the leadership of organisations with a great number of members to communicate your message to their members, backed by their personal validation? This was a strategy we developed before the public launch. A reception was held at Buckingham Palace for the leadership of organisations such as the Forces, the Police, the Fire Service, The Scouts and Guides, youth organisations, etc. We asked them to espouse our cause and make it their own. And they did:

- The Metropolitan Police raised £300,000

- The London Fire Service raised £185,000

- The Scouts and Guides raised £830,000

- Youth Club UK raised £100,000

How to handle an avalanche of gifts (a nice problem!)

The more an appeal director delegates, the more gets done. The trick is to clarify what you want done and then recruit the person with the ideal qualifications to do it – voluntarily! We were worried we would be overwhelmed with the public's response when we went public. The trustees had restricted the number of staff whilst a workflow assessment was carried out. Very luckily for us, we were able to arrange for the Midland Bank to receive, bank the funds and thank donors during the first three months of the public appeal, until we were given the go ahead to take on the extra staff we needed. The bank's staff did the work after office hours and they recruited many of their former staff members to help too. They could not have been better qualified to do the job and were a godsend.

The cost of publicity

A journalist called me towards the end of the public part of the appeal to say that we should be ashamed of ourselves; he had worked out that we must have spent about £6m on publicity for the appeal and that this was a gross waste of public money. He asked what we had to say for ourselves. To his surprise I thanked him enthusiastically for the research and reassure him that almost all the publicity costs had been provided pro bono. I don't think that is what he wanted to hear.

I have always found, with appeals, that sponsoring the appeal brochure and other promotional items, such as the website, is an attractive option for company giving. It highlights their generosity and their giving at an early stage and so gives confidence to others to follow their lead.

Other fundraising initiatives

A wide range of fundraising methods was used during the appeal, apart from the weird and the wonderful, the unusual and the imaginative ways funds were raised by the public.

The leverage gift

At the start of the exercise to secure big gifts, the Wishing Well Appeal made a special presentation to the Variety Club of Great Britain and won a pledge of £3m (which the club went on to raise during the public appeal). There was also a very helpful pledge from one donor who said she would give £1m if the appeal could find nine others to do the same thing. This was the excuse to ask for such a large donation from those whom research had indicated could give at that level. As can be seen from the schedule (above, right) it did not quite work out like that. But it was a great method of raising people's sights to give at the top level, which should always be where major donor fundraising starts.

The effect of a successful capital appeal

The success of the Wishing Well Appeal had an incredible effect on the hospital. It seemed as though the whole country was rallying round to make sure it continued as a centre of excellence and that the very best was made available for the UK's sick children. This was a terrific boost to the morale of patients and their families, staff and everyone concerned. It raised the profile of the hospital to a new level and every area of activity benefited – especially the ability to recruit top level staff from around the world. It allowed many people to become stakeholders and to feel part of the enlarged family of the hospital. It was also the start of a highly successful on-going fundraising department which, today, raises around £50 million per annum.

Showing gratitude

It is amazing how many charities, at the end of an appeal, just take the money and run. It does not seem to occur to them that they should gratefully thank those who gave and show them how their money is making a difference.

The hospital went out of its way to try to thank as many as possible of its supporters – although with 60,000 donors, this was not easy. The appeal devised many ways of saying thank you. Two key functions were a service for 2,000 guests in Westminster Abbey, followed by a reception and a Royal Garden Party at Buckingham Palace. For those donors who raised funds to name areas or rooms in the hospital, a special opening for that area was offered, just for them, their contacts and friends, before The Princess of Wales opened the whole building.

Sharing the knowledge

It is heartening that many charities, although in competition with others, still share their knowledge, in the interests of their beneficiaries.

Because of the avalanche of response achieved by the Wishing Well Appeal, the trustees were conscious that the funds received might have detracted from other charities during that time. Indeed at one stage the appeal was raising £2m a month and, like a liner, it was difficult to bring it to a sudden halt, especially when so many supporters had planned more fundraising events. As a result, the trustees determined to do all they could to pass on useful information about some of the innovative methods that had been used.

To assist other charities, the hospital generously gave individual advice as well as a seminar for 130 charities. They allowed me to advise other children's hospitals and many UK children's hospitals have since held their own successful appeals, inspired by the Wishing Well Appeal experience. The hospital also encouraged me to write my book, Capital Appeals: the Complete Guide to Success,which was sponsored by one of HRH The Prince of Wales's charities – Business in the Community. This book, which can be ordered via the Marion Allford Associates' website, gives a detailed account of the Wishing Well Appeal and how it was established and run. It also explains how these techniques can be applied to any appeal.

Conclusion

To continue sharing the knowledge, after the appeal, I established a fundraising consultancy, Marion Allford Associates, which continues to advise charities in the UK and overseas. The consultancy has a team of marketing, management and fundraising consultants and carries out a wide range of advisory activities, as well as assisting in the establishment of many new, national charities.

I am delighted Ken Burnett and colleagues have set up SOFII. It will do so much more to share knowledge on special and unique fundraising initiatives. I am sure it will inspire many people all over the world to be creative and to keep coming up with fundraising methods that are effective, lucrative and, hopefully, fun.