CDE project 1 section 1: rethink language to reflect, respect and engage with the views and feelings of supporters

- Written by

- The Commission on the Donor Experience

- Added

- May 01, 2017

Enhancing the ways we use language

Andrea Macrae and Chris Washington Sare, April 2017

Reviewed by Matthew Sherrington

1. Rethink language to reflect, respect and engage with the views and feelings of supporters.

Language reflects attitudes, beliefs, relationships and cultures of behaviour. The values, views and feelings of supporters are at the heart of all charitable giving and its impact. Charities can better focus on, respect and ingrain the views and values of supporters by fundamentally reorienting the language used to communicate with and about them.

How many people do you know who give to charity and would say ‘I donate to charity’ or would describe themselves as ‘donors’? Businesses and companies giving to charity might formally and publicly use words like ‘donate’ and ‘give a donation’. People, though, in most contexts, use the words ‘give’ or ‘support'.[1]

This isn’t just a matter of semantics. The words we use reflect the way we think – our views and beliefs about things and relationships.[2] The act of ‘donating’ is usually associated with giving money [3] and to refer to someone as a ‘donor’ is to refer to them primarily in terms of that transactional relationship. The word ‘give’ has broader associations – we ‘give’ all sorts of things. [4] The word ‘support’ is broader still: a person can support a charity in many ways, for example, through volunteering, raising awareness, and so on. While the word ‘give’ moves further away from a focus on monetary transaction, the word ‘support’ moves yet further away from a transaction altogether, as it incorporates the meanings ‘give assistance, encouragement or approval to’. [5] ‘Supporters’ puts an emphasis on personal approval, assistance and collegiality, in comparison to the more transaction-focused ‘donors’, and can more fully encompass the broader role and value of supporters within charities.

There is an important link between use of dehumanising terms to refer to supporters (e.g. prospects, mid-value donors, etc.) and insensitive behaviours towards them, such as lack of consideration of possible changes in personal circumstances, or general lack of consideration of the human being – the person – behind the terminology. A simple, sensible and sensitive practice is to use terms to talk about your supporters which you would feel comfortable using in talking to them, and which you would feel comfortable being used to refer to or address you or a member of your family. One means of helping to instill this practice is to imagine having a supporter present in the meeting at which you might ordinarily use these terms – or, even better, have one person in the meeting adopt the role of a supporter, and consider and feed back on the language and approach of the meeting from that perspective. It’s a great way of staying mindful of supporters’ viewpoints and experiences, and of keeping language, and attitudes and approaches to communication with supporters, human and respectful.

[1] The phrase ‘give to charity’ occurs nine times more often than the phrase ‘donate to charity’ in the British National Corpus, a 100 million word collection of samples of written and spoken language designed to represent a wide cross-section of British English from the latter part of the 20th century (phrase search performed using the ‘Phrases in English’ search tool).

[2] Turner, R. C. (1991), ‘Metaphors fund raisers live by: Language and reality in fund raising’, in Taking fund raising seriously: Advancing the profession and practice of raising money, eds D. F. Burlingame and L. J. Hulse (San Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers).

[3] The British National Corpus described in footnote 1 can be indicative of associations. Within this corpus, the phrases ‘donate money’ and ‘donate some money’ occur 13 times more often than ‘donate time’ and ‘donate some time’, and also 13 times more often than ‘donate goods’ and ‘donate some goods’.

[4] In the British National Corpus, the phrases ‘give time’ and ‘give some time’ occur almost as often as the phrases ‘give money’ and ‘give some money’ (the latter occur only 1.14 times more often).

[5] Oxford English Dictionary.

Shifting from dehumanising and profit-prioritising habits of expression to more supporter-centric language can carry a kind of ‘cognitive cost’ initially: it may take more effort, as any adjustment often does. You also might end up with longer, potentially more awkward terms of reference. The crux of the matter is, though, that this is not simply about swapping one set of terms for another to be more politically correct: language both reflects and influences beliefs and behaviours.

Just as the way charities refer to supporters reflects and communicates values, so too does the way charities refer to roles within their organisations. Compare ‘Supporter Experience Team’ and ‘Donor Stewardship Team’: ‘experience’ focuses more on the supporters’ feelings about their interactions with the charity, and gives less of a sense of preclusion of choice, in comparison to ‘stewardship’, which suggests a priority of channeling supporters along a pre-set path (a ‘steward’ manages, administers, controls and directs) [1]

Likewise, consider ‘Supporter Team’ and ‘Donor Acquisition and Retention Team’. If you had lots of money to give, how would you feel about being approached by a ‘Major Prospect Fundraiser’? How might a business feel about a ‘Corporate Donor Cultivation Officer’ vs. a ‘Philanthropy Partnership Advisor’? Would you rather be approached by someone who sees you as a good ‘prospect’ for boosting an organisation’s funds, or by someone who sees you as a potential ‘partner’, offering a collaborative relationship and some help for you to achieve your personal philanthropic goals? [2]

Researcher Russell N. James recently surveyed 3188 people in America to test 63 job titles in four charitable contexts: a charitable bequest gift, a gift of stock, a gift of real estate, and a charitable gift annuity. People were asked which person they would prefer to contact to discuss each gift option, based on their job titles. He found that institution-focused job titles performed worst, in particular job titles which involve the word ‘development’. James’ study concludes that if some of an organisation’s job titles are institution-focused, reflecting institutional priorities over and above supporters’ priorities—if there is a risk that the job titles which appear in letters, emails, on webpages, etc. might be off-putting to potential supporters—then reviewing these job titles and re-orienting them towards supporters’ perspectives and priorities could be really beneficial. [3]

[1] Oxford English Dictionary.

[2] With thanks to Jonathan Andrews for this observation, drawn from his experience as a corporate partnership consultant.

[3] James, R. N. (2016), ‘Testing the effectiveness of fundraiser job titles in charitable bequest and complex gift planning’, Nonprofit Management and Leadership. doi:10.1002/nml.21231. With thanks to Ken Burnett for drawing my attention to this article.

Case study: Save the Children’s supporter focus

For several years, Save the Children has been developing and embedding a new strategy in their approach to supporters, moving away from classic stewardship towards a focus on the experiences of their supporters. Save the Children challenged the terminology they applied to their supporters. This involved reconsidering the terms and distinctions involved in the single category system that supporters are traditionally governed by, recognising that a supporter might be, or might want to be, both an ‘individual giver’ and a ‘campaigner’, for example. Save the Children enhanced the ways in which they offered choice in kinds of involvement with the charity, and improved the ways in which communications with a supporter reflected and responded to their preferences. They also looked at the ways they used terms such as ‘supporter’ and ‘campaigner’, reconsidering what it meant to identify and label a person according to a particular interaction with the charity, rather than recognising him or her as a person, first and foremost, who once or more had chosen to contribute to the cause.

The strategy is part of an overall programme to become more supporter-centric and to make supporters more visible and integrated within the organisation. Being a fairly recent development, data gathering on its impact upon supporter satisfaction is ongoing, but the strategy has positively impacted upon communication with supporters and internal cultures of behaviour. For example, there is now a lead senior role dedicated to overseeing, integrating and improving the holistic supporter experience and changing communications planning to start with the supporter, rather than with individual campaigns and activities.

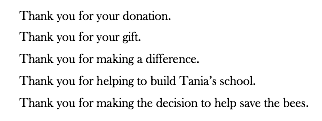

This kind of rethinking works at every level of language use, from department names to phrasing thank you letters. Compare the following:

As we move down the list, the emphasis moves further away from a focus on the money donated and towards the conscious generosity, impact and agency of the supporter.

Lots of elements of language use, internal to an organisation and external, can be reworked to better reflect and respond to the priorities and perspectives of supporters. Most of the recommendations in this project derive from this essential fundamental principle.