CDE project 20: fundraising investment

- Written by

- The Commission on the Donor Experience

- Added

- May 31, 2017

Being honest and telling the truth well about fundraising costs

Giles Pegram, Allan Freeman, Angela Cluff,

David Ainsworth and Andrew O’Brien, April 2017

Overview

Donor research

- The Commission has undertaken qualitative research (focus groups) with donors. Donors are concerned about charities wasting money on salaries, on market and fundraising, and on offices. This is consistent with research from NCVO. https://tinyurl.com/m2gue29

- Many donors express this concern, but they also think that ‘spending on fundraising must be effective’, because charities continue to spend on it.

- Donors are reassured when charities are upfront and honest about how they spend their money and like to see charities concerned about their financial effectiveness.

- We think that this means that it is vital that charities are able and willing to explain their costs of fundraising. Not all donors will be interested in this information, but for those who are interested, it is important that individual charities explain their own approach. In situations where stakeholders; donors, the public, and the media; ask questions, each charity must be able and willing to explain openly and honestly.

Principle 1

Investment in fundraising is a requirement for an effective charity

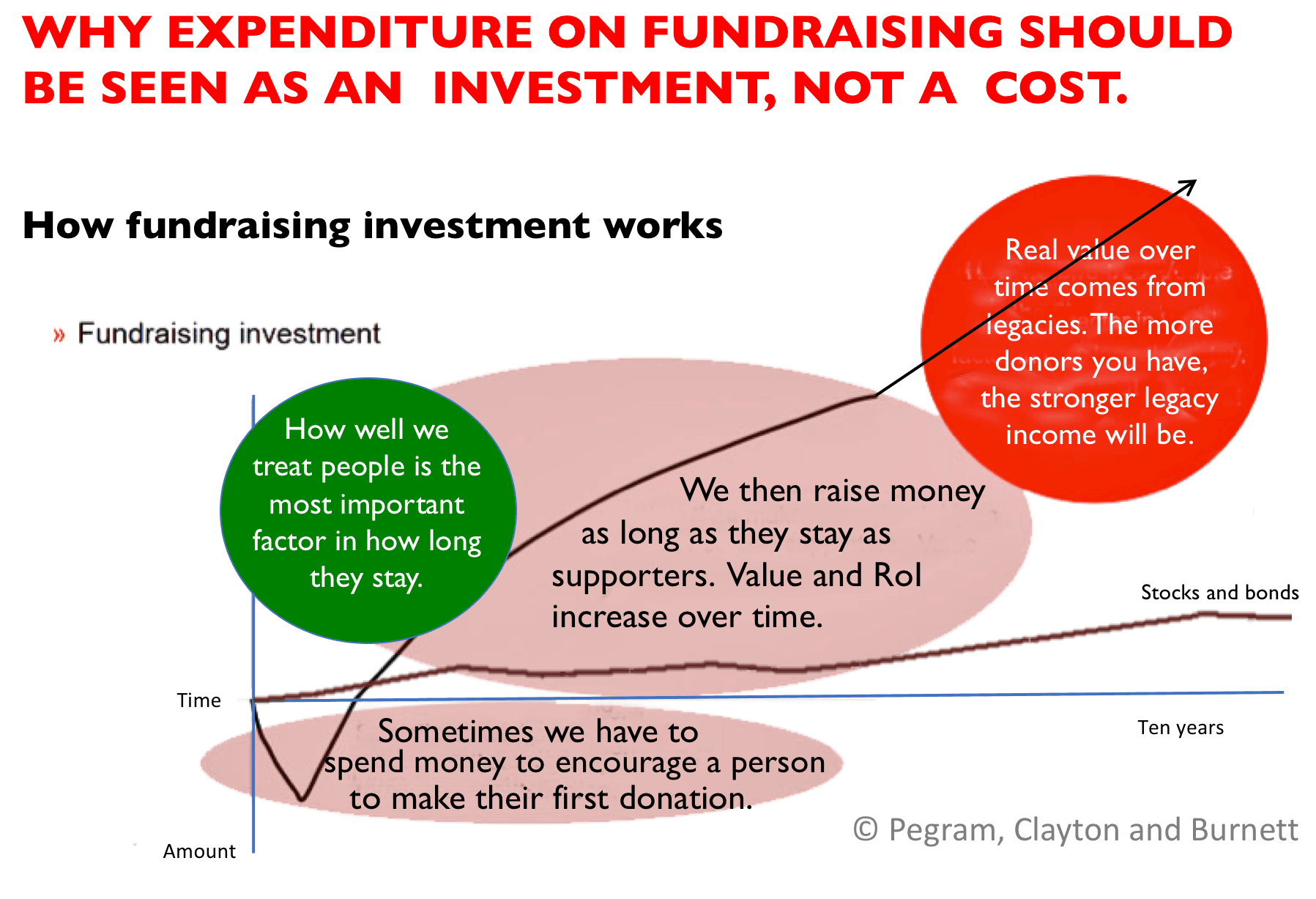

Charities are a better long-term return if they think of fundraising expenditure not as a cost, but as an investment that secures longer-term income, the charity’s sustainability and ability to better deliver its mission, and its longer-term relationship with supporters through a better experience.

If all individuals saw fundraising in this way, charities would please more donors and raise more money.

Attitudes to and strategies for investment are the concern of each charity, but there is a perception in some parts of some fundraising departments that cheapest is best and that investment in doing things right is not a priority. This perception is often a consequence of the organisational culture created by CEOs and trustees which demand fundraisers reduce costs and increase income. However, this is tragically wrong. Decisions should be based not on lowest cost but on long term income. (See CDE project 15: The role of trustee boards and senior managers.)

For example, charity managers must balance the short term income needs of the charity with long term financial health.

Certainly, giving more confidence that fundraising investments are being spent wisely and having a positive impact can only help to improve public confidence, creating a more supportive environment for charitable giving.

There are charities failing because they have underinvested and invested badly. This applies both to investment in fundraising activity and in people.

(The chart, below, is a simplified version of a chart commissioned by Giles Pegram and produced by Allan Freeman. A rigorous version, including actual figures from a variety of charities, is currently being worked on by Lenka Morgan from REAL fundraising. It will be added to this project when completed.)

Principle 1: Actions

- The case for prudently investing a sensible part of a charity’s reserves in fundraising (versus other options such as stocks and bonds) should be clearly considered, and, if appropriate, clearly made. Charities are obliged to keep reserves. Sometimes using reserves for fundraising is a good thing; sometimes not. Each charity needs to make conscious judgements based on their situation.

- SMTs and Trustee Boards should understand the importance of seeing fundraising as an investment.

- Every charity should decide how much to invest in fundraising and in what areas, linked to the strategy of the charity, its appeal to prospective donors, its position in the sector, and its attitude to growth. The charity must decide if it wants incrementalism or step change. This is an organisational decision and not a fundraising one.

- Charities need to avoid stop/start activity in fundraising. If the SMT and trustees want incremental growth, this should determine the fundraising director’s three-year plan. If the SMT and trustees want significant growth, then this should drive the fundraising director’s three-year plan. A stop/start mentality is a great drain on donor income.

- Each charity should openly discuss the fundraising business model in SMT and with the board of trustees. The factors that influence that business model are too many to be explored here. Matthew Sherrington’s blog, https://tinyurl.com/n7mb2s2 is a very good read.

- When investing for growth both there needs to be a strong business case which is challenged and monitored carefully. When writing a fundraising plan for growth, it should have enough organisation buy-in so it is not about the fundraising director. It must include the finance director, the CEO, and trustees.

- Fundraising managers should, where appropriate, make the case to invest more in recruiting and retaining the right people.

- CEOs need to be completely aligned with fundraising directors and their fundraising strategy. Together, they can be certain that the fundraising strategy is embedded into the organisation by trustees and SMTs. In doing that, fundraising directors and CEOs equip them to defend decisions on fundraising investment.

- When creating the fundraising strategy and plan, the fundraising director should start by looking at the charity’s own experience, strengths and weaknesses. Use what you know and have learnt and then use step change/innovation where opportunities exist or needs drive you. Do not start with a blank sheet of paper, and Do not ignore your own history. And certainly, do not ignore your existing donors who have got you where you are.

- Every employee in the charity should be able to explain why the charity invests in fundraising.

Principle 2

Good measurement means fundraising is more cost-effective, and donors like that

As both outlay and income can be measured, or at least assessed over time, there should be a clear understanding among donors and fundraisers that fundraising investment is generally a good thing for the charity.

Principle 2: Actions

- The returns charities get from a balanced fundraising portfolio should be carefully recorded, understood and made available to donors. Fundraising (the development of relationships with donors) done well is fundamental and can be an impressively cost-effective activity; therefore, measurement should be according to a balanced scorecard. It needs to include short, medium and long term metrics. It should include a return on investment.

This is covered fully in CDE project 3 - satisfaction and commitment.

Principle 3

Charities must be accountable for the costs and benefits of their investment in fundraising

Accountability and transparency and effective measurement and planning are key. However, these alone are not enough. The charity must proactively communicate to be successful.

Donors have every right to be concerned about the effectiveness/efficiency of fundraising. They are entitled to proper explanation and making their decisions on whether to support the charity.

Principle 3: Actions

- Fundraisers should remember that donors are giving to the cause, not the organisation.

- Explain the charity’s situation positively. Without implicitly criticising others.

- Charities should report about their performance in their annual reports, including addressing failures where appropriate. This reporting should be considerably over and above the statutory requirement.

- Charities should be honest about their fundraising strategy in their annual report. Simply and clearly write about the charity’s approach to fundraising,.

- Fundraisers must be able to explain their organisation's approach to fundraising to donors who want to know but they should not assume that they all want to know

- Where donors perceive that the charity is wasting money on them, endeavour to act accordingly. This drives better fundraising investment. Where the charity is unable to act on their wishes, explain why. (See CDE project 13: giving choices and managing preferences.)

- Give fundraisers a Q&A sheet on how to answer questions about investing in fundraising, and perhaps give an example. Maybe ask the following: ‘We would like to spend £3 of your £10 donation to help encourage another donor to give £10. Do you think that’s reasonable?’

Principle 4

Some people are disposed to be donors and some are not.

Principle 4 Actions

- It is generally best to focus investment on those with a pre-disposition to support the cause.

- A charity should not try to invest in getting committed non-donors to give. Pay more attention to perceptions and feedback of supporters than of the wider general public, for this reason.

Principle 5

A charity should only undertake activities which its senior leaders would feel they have sufficient evidence for a robust defence if challenged.

Principle 5: Actions

- If an activity does not pass the above test, a charity should not do it.

- Fundraising directors should observe and assess all their fundraising activities. Any that a reasonable donor might find unacceptable should be identified and explained and justified to the CEO.

- Charities must be ready to defend their actions when questioned. If a charity’s trustees and chief executive are not willing to defend a charity’s practice in public, if called upon, the charity should question whether it is something their organisation should continue.