Decolonised fundraising that works: myth or reality?

Lizi Zipser, director of global strategy and insights at Blue State looks at the complexities of decolonising charity appeals, and shares why getting it right isn’t as simple as just changing photography.

- Written by

- Lizi Zipser

- Added

- January 27, 2022

For as long as I can remember, the sector has been at odds with itself when it comes to how we represent the people our organisations exist to serve. Fundraisers are being challenged internally and externally to move away from the implicit power dynamics of ‘white saviour’ appeals, and create balanced, representative and inclusive work.

In recent years the public has also raised their voice on this issue, criticising charities for perpetuating stereotypes, for emphasising the negative and not the positive, the struggle and not the power and agency of communities around the world.

But as many readers may know by now – when you serve donors what they ask for, they don’t always put their money where their mouth is. This gap between the values of an organisation and the need to raise money has put a lot of fundraisers between a rock and a hard place. How do they provide lifesaving funds if they can’t use the tactics they know would be most effective?

As consultants to our clients, we have seen this shift accelerate in the last few years – there is now not a single pitch, meeting or brief that doesn’t ask us how we will evolve an organisation’s fundraising programme in a more ethical way.

But while the ambition is there, many organisations trying to achieve this can find this leads to an internal back-and-forth between fundraisers, communications and programme teams – often misaligned on what ‘ethical’ means for them, and what it means for image and language choices.

We’re here to say – yes decolonised fundraising is possible. It can work – but to work you have to completely change your mindset and the focus of the conversation. Changing your images is not enough. You need to change the model and work with human psychology to understand why people would give to your cause when you can’t serve them visually upsetting appeals.

The scale of the problem

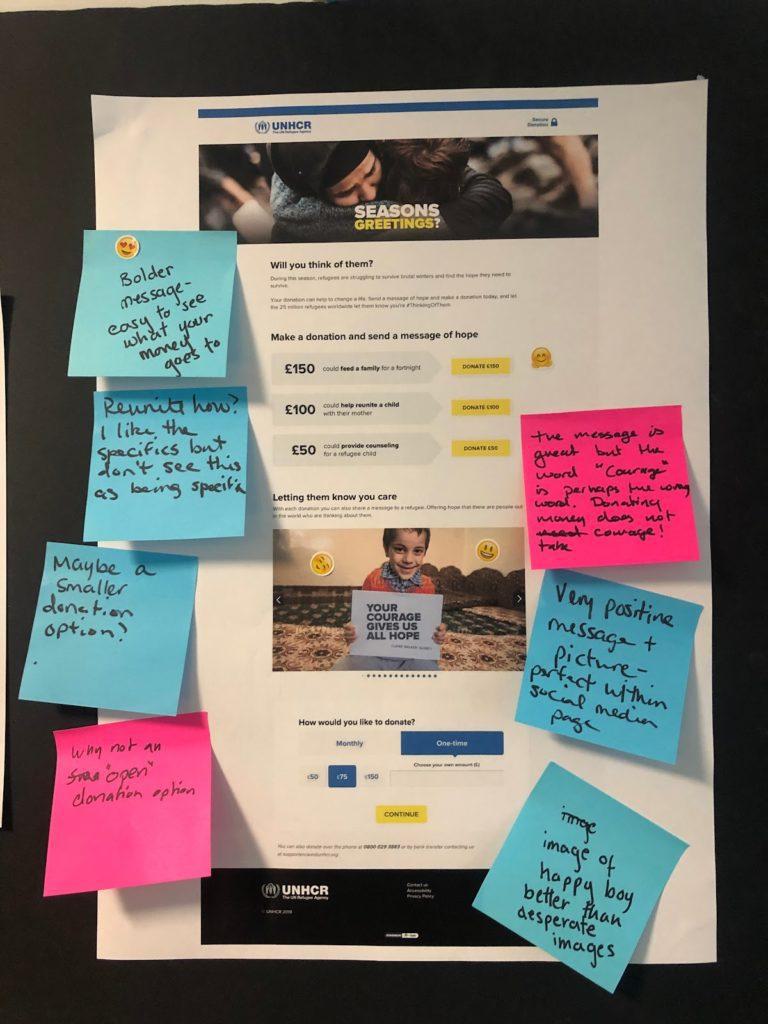

In order to help our clients and networks understand this issue better, we carried out new research earlier this year – with a theory as to what we might find. We expected to see at large scale what people tell us in focus groups and interviews – that they want charities to use more respectful imagery, and that they would donate to campaigns that use these more positive images.

But what we found shocked us.

We surveyed a representative sample of almost 1,500 people in the UK and found that while the majority of people could identify when an image was stereotypical, problematic and/or unrealistic, 67 per cent said they would still donate to them.

Out of these, almost one in five (23 per cent) elected to donate to an image they had just seconds ago indicated as problematic and portrayed children in an undignified way.

The findings held across all age groups, though interestingly, while still overall opting for stereotypical images, younger demographics were more likely to favour neutral or positive images than their parents and grandparents.

While we’d assumed that people would say they preferred positive images while still being more willing to donate to negative ones, we were taken aback by the reality check this provided. People themselves say contradictory things and are aware of their own internal biases.

There is something much deeper that compels individuals to certain images, and in a recent report we attempted to review the psychology and mechanism of why this is, through scientific studies and our own experience – showing how we could move away from the models that have worked so well for fundraisers in the past.

So what can you do about this?

First, stop and reflect. Some fundraising organisations, our clients included, are evolving their fundraising while still maintaining results. And they’re doing it by having a deeper understanding of the role their organisations and appeals play in supporters’ lives. It’s about breaking out of the traditional model and going beyond tweaking the language in the ad, email or pack. It’s a whole rethink.

Traditional fundraising relies on a model called ‘negative state relief’ – on creating a state of discomfort in donors, which they can alleviate by stepping in to help. Fundraising images and stories touch us, making us upset that the world could be so unfair – and it’s that strong emotion that compels people to donate.

This is the crux of the problem – and why simply making a switch to images that are more respectful can lead to lower donations. By diluting the emotion, you’re diluting the response. The answer isn’t to remove the emotion – it is to find different emotions, both positive and negative that will move people to action. This doesn’t need to be disrespectful to the people your organisation serves and can leverage how donors feel and what they gain, psychologically, socially or tangibly from donating to your organisation.

This means understanding your donors better and how your organisation fits with their identity, their need for belonging, their personal history and values, and how giving to the organisation connects them with others who also want to see a better world.

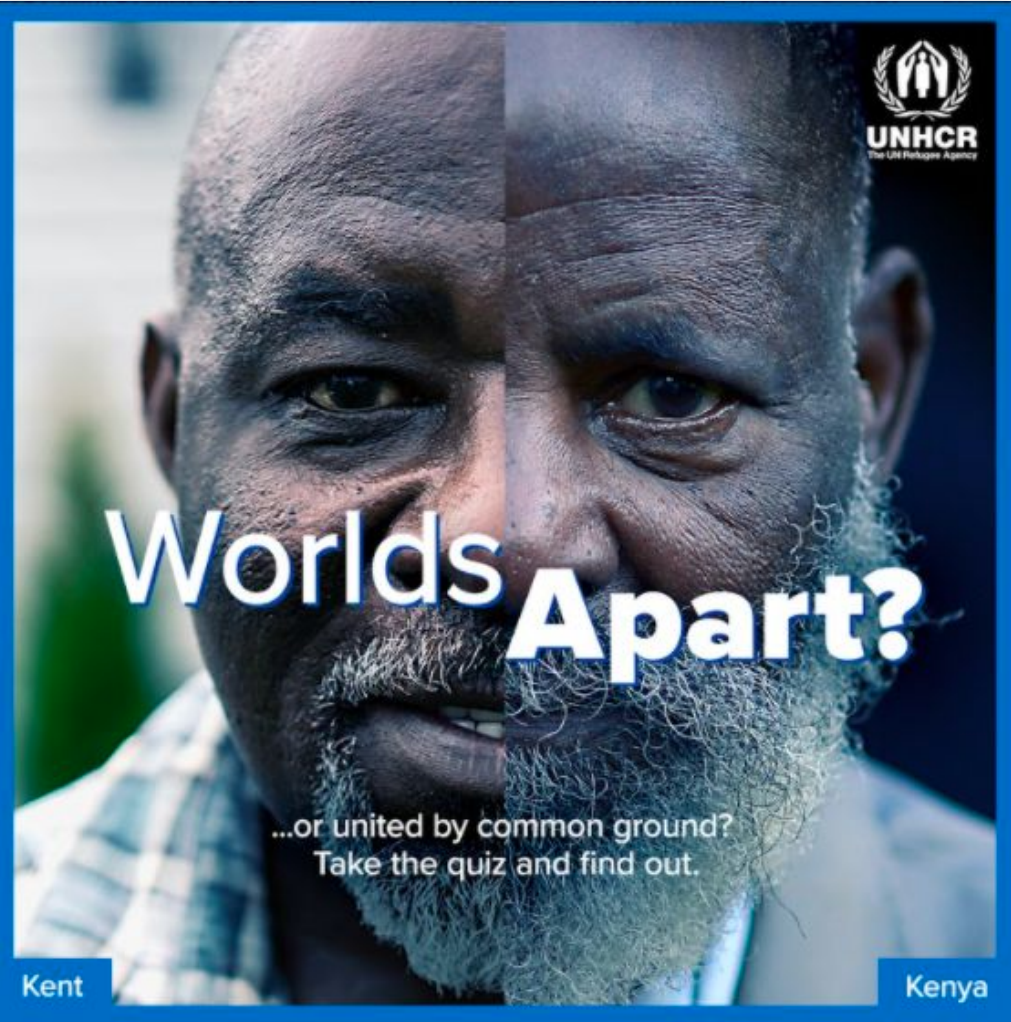

Our recent campaign with UK for UNHCR used this approach and saw really strong results.

After already raising a record-breaking £2.4 million during the first 10 months of the pandemic, our teams launched the Winter Appeal, responding to the feelings of frustration and distress from coronavirus to drive empathy for how refugees feel every single day. The campaign came to life via Facebook, YouTube, paid search and programmatic display activity to drive both consideration and conversion.

The creative focussed on the similarities between refugees and those going through the pandemic in the UK, to try to bridge the gap between our audience and those who we intended to help. The campaign raised more than £3 million and saw UK for UNHCR acquire 364 per cent more donors year-on-year.

This sort of route is a more complex journey, but it’s ultimately the more valuable, sustainable, and long-term option. In fact, some of our clients are raising three times what they were by completely reinventing their fundraising work, with higher lifetime value and donors more likely to continue engaging and giving after the point of acquisition.

So, if you’re being challenged to change your fundraising while meeting your targets, or if you tried and saw results slump – we’re here to say there is another way. But it may take more creativity and bravery to truly evolve the model and how the sector thinks about giving.

Editor’s note: The full report exploring Blue State’s research findings, literature review of psychological studies into fundraising, and examples of creative that are both more ethical and effective, can be downloaded from: