From beggars to buskers: what can modern charities learn from street artists?

Charitable giving is decreasing in the UK and yet the need for ‘belief-based’ organisations – both for and not-for-profit – has never been greater. To overcome this disturbing oxymoron, charities need to change their approach and transform their offering.

- Written by

- Steven Dodds & Clare Jones

- Added

- January 03, 2014

Walking past a beggar can be a deeply uncomfortable experience. Clocking the beggar from afar, most of us immediately start to play arguments in our minds: to give or not to give?

As we reach the beggar, we steel ourselves for the ask – ‘spare any change guv?’ – and we are forced to confront our mixed feelings. Whatever we decide, rarely are we sure that we made the right decision.

Contrast this experience with that of coming across a top notch street artist – a juggler, a violinist on a unicycle, someone chalking a Van Gogh painting. Instantly our curiosity is aroused. If the artist already has a crowd we simply have to know what all the fuss is about so our pace slows, we dawdle and are drawn toward the event.

The best street entertainers have their own stories and patter that they weave through their acts. They are interesting characters with nuance and depth, by turns comic and serious. We listen and watch.

The event becomes communal as the artists find a volunteer and involve the crowd. We experience it together. As the act ends a hat is passed and some of the crowd drift away sheepishly, but for many the decision of whether to give is an easy one. The street artist deserves his reward.

And so it is with charities.

These uncomfortable feelings of guilt and conflict are evoked not only by the pleas of a lone street beggar but also by charities on a much larger scale. They have become central to the widely adopted philanthropic model that, evidence suggests, is beginning to wear thin.

The ‘cap-in-hand’ model, favoured by almost all charities, relies on pointing out the differences between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’– creating sympathy and guilt to initiate action.

Yet a recent survey of ours conducted with charity donors who use social networks, who many think will be the future of individual giving, showed that 50 per cent of them agreed and only 19 per cent disagreed with the statement ‘charities are too reliant on guilt to prompt donations.’ (Source: DMS survey via Fastmap, 1,033 UK adults, April ’10).

The issue for charities here is that by relying heavily on the needy to prompt donations, their brands have become ‘infused’ with the beneficiaries they serve. Donors simply drown in a sea of victims wanting money.

In this tight economic climate, charities are feeling the pinch, wondering where to go next. They need to rethink their approach – the clear direction open to them is a new entertaining, interactive and enabling philanthropic model.

The new philanthropy: from dependent to enabling

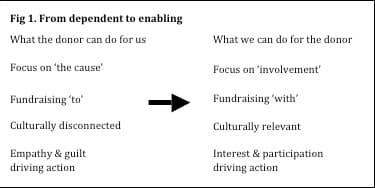

As the opening story of this piece suggests, the key shift required is to move from a model dependent on altruism to one based on enabling consumers to live more interesting and enjoyable lives while acting on their beliefs. (Fig 1)

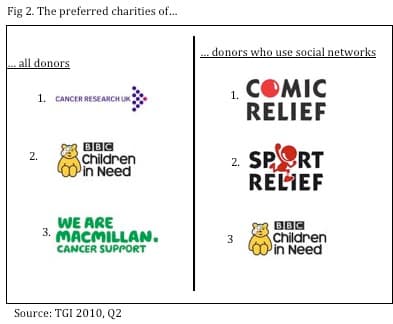

It is clear that this enabling model is popular with donors who use social networks. Contrast the ‘preferred’ charities of these donors, a younger demographic, with that of all donors in the UK (Fig 2).

Two of the top three in the UK – Cancer Research UK and Macmillan Cancer Support – are typical of many UK charities. Both are at least 50 years old with large portions of income coming from the traditional ‘dependent’ model.

Children in Need, Sport Relief and Comic Relief (founded in 1985) are considerably younger and noted exponents of the ‘enabling’ model. Clearly this model works – at the height of the worst recession for a generation all these charities have posted record levels of fundraising income.

While there is little doubt that the BBC, celebrities and hundreds of hours of air- time have contributed to their success, look beyond these and other reasons emerge.

These three charities focus their efforts on one day of the year, building the excitement towards this day and inviting people to be part of it. On the day a series of events – many broadcast live – form the focus of the fundraising.

The perhaps inadvertent brilliance of this model is that it is perfectly in tune with the broader cultural themes that have been ushered in by the social networking age.

The Comic Relief brand is inherently open and social in nature, owned by anyone that has ever been involved in a fundraising event, not just by a select few that work for the charity. The fundraising method is also highly participative and involving: fundraising ‘with’ not fundraising ‘to’.

Crucially, these charities also realise that it is not the cause that is differentiating but the marketing of it. They know that people are more likely to act when the communication and creative drama are focused more on methods of involvement and less on the cause itself.

Rage against the X-Factor

Another good example of this model is the pre-Christmas 2009 ‘Rage against the X-Factor’ campaign.

Charity supporters Jon and Tracey Mortor, bored with X-Factor winners reaching Christmas number one for four years running, campaigned to get Rage Against The Machine’s ‘Killing in the name’ to top the charts instead.

For any that don’t know the song, Rage’s slice of rock polemic is the ultimate anti-establishment track, slowly building to the final shouted refrain ‘F@#k you! I won’t do what you tell me!’ It was first released in 1992 and reached number 25 in the charts. To be Christmas number one in 2009 against a backdrop of highly refined sugary pop would indeed be an achievement.

That is exactly what happened. Many were keen to be part of this historic event and ‘the race’ built its own momentum, picking up 1.5m Facebook fans along the way.

Jon and Tracey, concerned with the plight of the homeless at Christmas, had the foresight to ‘dedicate’ the whole campaign to Shelter. They encouraged anyone who bought the single to donate to the charity and over £100,000 was raised, plus an undisclosed donation from the band. They also attracted a sizeable heap of positive media attention and a large dollop of brand kudos for being part of something so ‘now’.

This landmark event demonstrates how bold, culturally relevant, enabling ideas involving charities can grab the public’s painfully overstretched attention.

Profit through partnership

In its Global consumer trends for 2010, Mintel recently predicted that ‘ethics will play a large part in rebuilding brands… consumers want ethical responsibility to be a chief concern.’ In this environment, partnerships between commercial operations and charities are a natural solution.

The poster child for these partnerships is undoubtedly (RED). The union between The Global Fund and some of the world’s biggest brands, including American Express, Dell, Nike and Starbucks has raised more than $140 million through brand extensions from mobile phones to clothing.

The opportunity is there for increasing innovation in the partnership space with charities using consumerism to forward their agendas.

If charities act quickly they have the chance for their brand to sit equally alongside the commercial one, or perhaps even dominate, instead of tagging along for the ride as they often do now.

The stage awaits

These are morally reflective times, dominated by climate change, the global banking crisis and MPs’ expense scandals. Focus has turned to the motivations of organisations and we have again begun to question how to create a fair and equitable society.

With greater emphasis placed on personal responsibility to create positive change, the opportunity for ‘belief-based’ institutions like charities is increasing.

But charities have to change the script. Research points to the need for a re-purposing of their models of funding and engagement with less focus on ‘the cause’ and more on the consumer’s reason to be involved.

The perhaps sad truth is, the majority of us simply cannot or will not give as much attention to these causes as charities would like. If more charities are to step onto centre stage, they need to put down the begging bowl and polish their ability to entertain.

© Steven Dodds and Claire Jones' article was first published on SOFII in 2011.