Heart and soul: Charles Dickens on the passion and power of fundraising

‘Have a heart that never hardens, and a temper that never tires, and a touch that never hurts.’ Charles Dickens.

- Written by

- Aline Reed

- Added

- April 02, 2011

Although not intended as such, this is an excellent piece of advice for fundraisers everywhere. It appears in Our Mutual Friend,* the final novel by Charles Dickens.

As this SOFII exhibit shows, our profession didn’t escape his satirical pen. In the same book, Dickens is fairly uncomplimentary about fundraisers (or ‘corporate beggars’ as we prefer not to call ourselves).

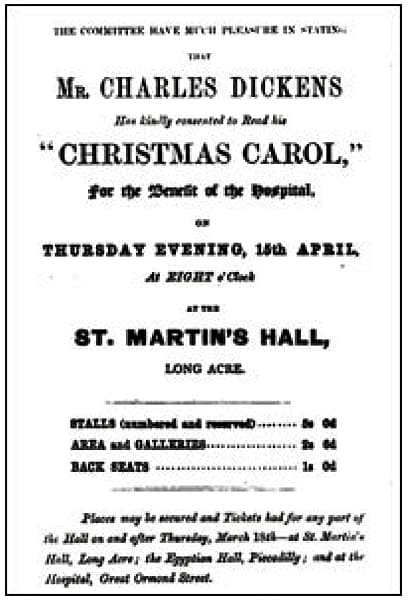

Despite this, surviving evidence suggests that Dickens was a pretty effective fundraiser himself. We have found a couple of examples of how he helped raise money for his chosen cause, The Hospital for Sick Children, which became Great Ormond Street Hospital. And while writing styles may have changed, he can still teach us a thing or two.

Founded by Dr Charles West, the Hospital for Sick Children was the first in the UK to offer in-patient care to children only. It depended on voluntary donations to meet its running costs, which were raised by subscriptions, donations and fundraising events.

A few weeks after the hospital opened, Charles Dickens published an article called ‘Drooping Buds’, which appeared in his journal ‘Household Words’. Excitingly, you can see the original here.**

Its subject is child mortality, but that’s an example of jargon, which Dickens took care to avoid.

Instead he works hard to make the facts meaningful to the reader. As you’ll see, he starts by using statistics to demonstrate the high loss of life. For every one hundred children born, only sixty-five were alive after eight years.

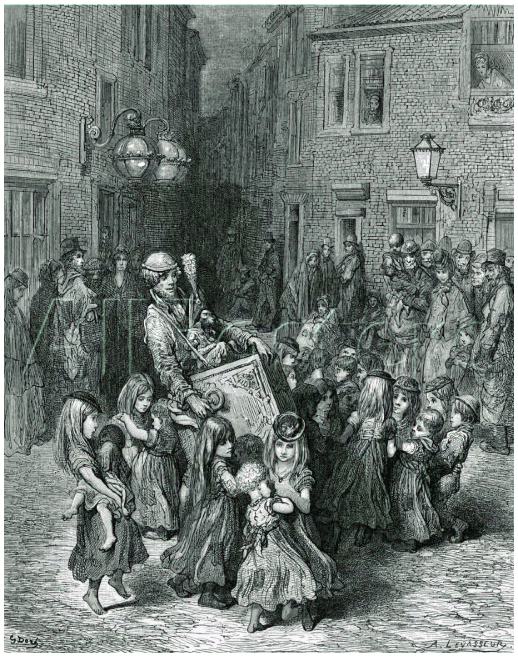

‘Of this great city of London – which, until a few weeks ago, contained no hospital wherein to treat and study the diseases of children – more than a third of the population perishes in infancy and childhood. Twenty-four in a hundred die, during the first two years of life, and during the next eight years, eleven die out of the remaining seventy-six.’

Well, that’s fairly convincing. But Dickens goes on to share an even more devastating piece of information.

‘Think of it again. Of all the coffins that are made in London, one in every three is made for a small child: a child that has not yet two figures to its age.’

He starts talking about little coffins – a horrifying image. And still he pushes it further, imagining the words of a lost child.

‘…“I,” said another shadow, “Am the lame misshapen boy who read so much by this fireside, and suffered so much pain so patiently, and might have been as active and straight as you, if anyone had understood my malady…”.’

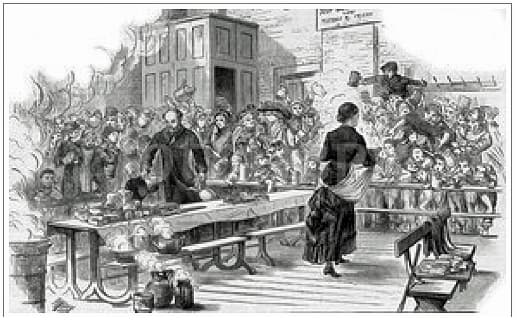

When Charles Dickens did a reading and gave a rousing speech at a Christmas fundraising event for the hospital he raised enough money to buy a new property – more than tripling its capacity.

So how did he do it?

John Forster, Dickens’ friend and biographer, can tell us more:

‘Dickens threw himself into the service heart and soul…he probably never moved any audience so much as by the strong personal feeling with which he referred to the sacrifices made for the Hospital by the very poor themselves: from whom a subscription of fifty pounds, contributed in single pennies, had come to the treasurer during almost every year it had been open.’

From this description, it seems he spoke with great belief and passion – and made his audience realise they were in a position to give.

Dickens went on to talk about a little boy he once met on a trip to Scotland.

‘There lay, in an old egg box which the mother had begged from a shop, a little, feeble wan, sick child. With his little wasted face, and his little hot worn hands folded over his breast, and his little bright attentive eyes, I can see him now, as I have seen him for several years looking steadily at us. There he lay in his small frail box which was not at all a bad emblem of the small body from which he was slowly parting – there he lay, quite quiet, quite patient saying never a word.’

Having established this tragic tale, Dickens went on:

‘Many a poor child sick and neglected, I have seen since that time in London…but at all such times I have seen my little drooping friend in his egg box, and he has always addressed his dumb wonder to me what it meant, and why, in the name of a gracious God such things should be!’

Then he added:

‘But, ladies and gentlemen, such things need NOT be, and will not be, if this company, which is a drop of the life-blood of the great compassionate public heart, will only accept the means of rescue and prevention which it is mine to offer.’

This compelling call to action led to over three thousand pounds being raised that night alone.

An explanation of Dickens’ success as a fundraiser can perhaps be found inHard Times, where he wrote:

‘there is a wisdom of the head, and a wisdom of the heart'.

The two examples we have of his appeals show that he spoke to both heart and head. In ‘Drooping Buds’, he shows how to take powerful statistics and drive home the human suffering they represent. In his Christmas address, he shows his skill as a storyteller. The shocking image of the little boy in the egg box stays with the potential donor, just as it stayed with Dickens himself. Appealing to heart and head, no wonder Dickens was such a good fundraiser.

© Aline Reed 2011

Author’s note: if this seems a little familiar, a first draft of this article appeared on www.bluefrogcreative.co.uk but some additional material has been added before submission to SOFII’s history project.