Tank Banks: more sensational fundraising from the First World War

Maybe this is a little cheeky: there’s not many fundraisers around today who would be able to give a tank as a special thank you. But we can – and should – create pride and excitement in our donors nevertheless.

- Written by

- Aline Reed

- Added

- February 18, 2016

I’d never heard of the Tank Banks until I watched Jeremy Paxman’s Britain’s Great War documentary, screened to mark a century since the outbreak of the First World War. But it was a really remarkable fundraising campaign. Initiated by the government, cities were pitted against each other to raise money to finance the war.

Fundraisers often discuss the best way of thanking their donors. If you’re ever in Ashford, Kent you’ll see an example that sets the bar pretty high.

In 1919 the people of Ashford were given a tank to thank them for their financial support for the war. One hundred years later, it’s still there and it’s the last such reminder of an amazingly successful fundraising campaign that toured UK towns and cities, raising millions.

It’s November 1917 and the public get their first glimpse of a revolutionary new weapon – the tank. Two of them were the highlight of the annual Lord Mayor’s Show in London. It may be hard to imagine now, but the tanks were stars and the government decided to capitalise on their popularity.

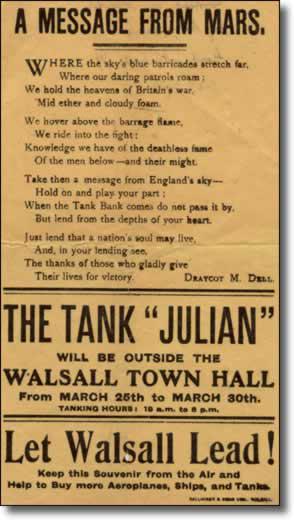

Six serving tanks – named Julian, Old Bill, Nelson, Drake, Egbert and Iron Ration – became the figureheads of a nationwide fundraising campaign and were sent on a tour of the UK. Before their arrival, flyers like this were dropped from aeroplanes to build up a sense of excitement.

Towns came to a standstill when the tanks arrived. Officials and celebrities made stirring speeches and then came ‘the ask’.

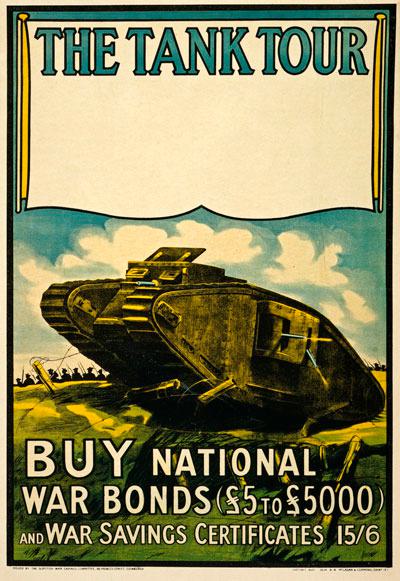

People were asked to buy War Bonds and War Saving Certificates. These – I’ve just learned – work in two ways. They give the government cash, but they also take money out of circulation, helping to control inflation. It was considered patriotic to buy War Bonds and so it was considered acceptable to offer a return on investment that was below the market rate.

It’s interesting to note that the public in Germany was also being asked to buy War Bonds with a similarly patriotic approach.

Back to the Tank Banks though.

You can imagine the excitement when the tank rolled into town, complete with soldiers bearing arms. Wikipedia informs me that two young women were generally put in charge of the stall selling War Bonds. With men generally the household breadwinner, it’s clear a fundraising mastermind was behind this scheme – he (most likely) seems to have thought of everything.

And that includes setting a fundraising target for each town or city and getting them to compete against each other. Apparently that worked best in highly populated industrial towns like Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow, Swansea, etc.

Of course, the result of the Tank Bank’s week-long stay in a town was reported in the national newspapers and so the pride of its citizens was at stake.

A whopping £14 million of War Bonds were sold in Glasgow, over £6 million in my home city Birmingham. But neither city was the winner. That honour went to West Hartlepool, in the proud North of England. The people of the town contributed £2,367,333, a massive £37 per person. As a reward for their generosity, they won Egbert (one of the touring tanks).

Less than 20 years later, council officials voted for poor old Egbert to be scrapped. So much for sending a tank to say thank you.