How I wrote it: the Salvation Army UK’s first large-scale cold mailing

In this, the fifth of a series of interviews with leading fundraising writers, Pauline Lockier talks to Fergal Byrne about a fundraising appeal letter written for the Salvation Army in 1990 which subsequently became their control for eight years. In this conversation Pauline tells Fergal how she wrote the letter and what really matters in making sure this kind of letter is a success.

- Written by

- Pauline Lockier

- Added

- December 18, 2012

Fergal Byrne: Can you tell me the background to this project?

Pauline Lockier: It was 1990. This was the Salvation Army’s first foray into large-scale cold direct mail and the first time they were going to spend a significant sum of money on recruiting donors. So it was quite a nerve-wracking project. If it hadn’t succeeded they probably would never have done it again, because they wouldn’t have been able to justify it.

FB: How did the campaign do?

PL: It was fantastically successful and became the control for the following eight years. Even when it did get beaten it was so marginal that they continued to send it out for another four years. We think that, over the years, this appeal was probably seen by the entire adult population of the UK. It raised about £5 million and about 300,000 donors over its life.

FB: How was the letter conceived?

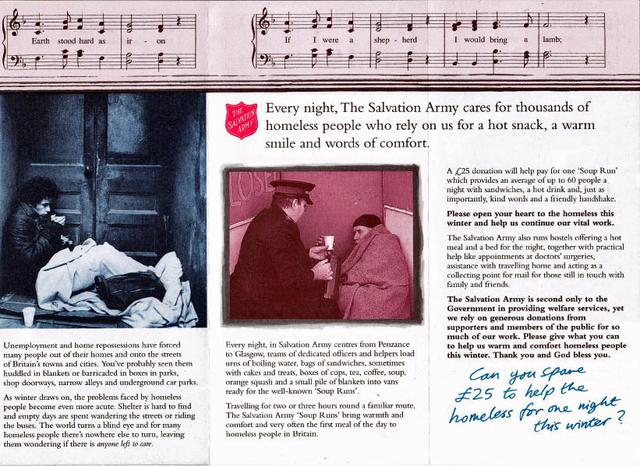

PL: The story that you read in the main body of the letter and the leaflet is very much my experience, it’s what I witnessed when I went on the soup run. I was there, I watched the people as they worked, I watched them interact with homeless people. This is not something you would have any idea about unless you’ve been there. There were a lot of people sheltering in doorways at the time but nobody thinks about what happens after dark. Where do these people go? Where do they stay? It’s just glossed over in your consciousness. You see them, you forget. So really my big concern when writing this was how do I get people to actually look at something they don’t want to look at and stay with that person, stay with that experience and homelessness.

FB: How did you decide in whose name the letter was going to be written?

PL: Right from the beginning I struck off a lot of possibilities. It couldn’t be a homeless person telling his story, because people don’t talk about their lives in that way, if they talk about them at all. I didn’t feel it would work from an outside perspective, someone like me or a donor or a supporter, watching the Salvation Army work. It really had to be from the perspective of a major, so we settled on William Cochrane and it had to be told with a we, us, I, me perspective throughout.

FB: The Salvation Army clearly has a long and respected history - how did it use this?

PL: When I was doing research in the 1990s, the sentiment that surrounded the Army was basically the Blitz, the East End and War Cry. I think it still is. There’s also folklore around the whole way they look, a bit Dickensian Victorian England. There is a certain amount of Christian, with a capital C, but much more about everything that Christianity stands for: goodness, kindness, hopefulness and all those things, Christianity with a small c.

So instead of peppering the copy with you, you, you, which is pretty standard direct mail practice, I tried to instil this letter with us, but not just us, we do, it’s us, we are. I wanted to convey that the Army, as a body of people out at work, are very dedicated, very committed, very non-judgemental, very willing to help anyone, no matter what. There are very rarely happy endings, but they just carry on, keep on doing our work. They are not evangelical, so throughout the copy there is no belief, there is no what I call mild bible bashing, it’s all about hope. At the end I said thank you, thanks for caring and may God bless you.

They work in a populist way, you don’t feel you are being preached at. So that’s why picking the tone was very important. We had to convey what they are in a way that played back people’s memory of what they think they are – the theme of the piece. You need to be realistic about what people think the organisation is, as much as you might not like it. You are not trying to change people’s minds – a view someone has held for 25 years is not going to be undone in a piece of mail that they pick up at Christmas.

FB: Can you tell me about the theme?

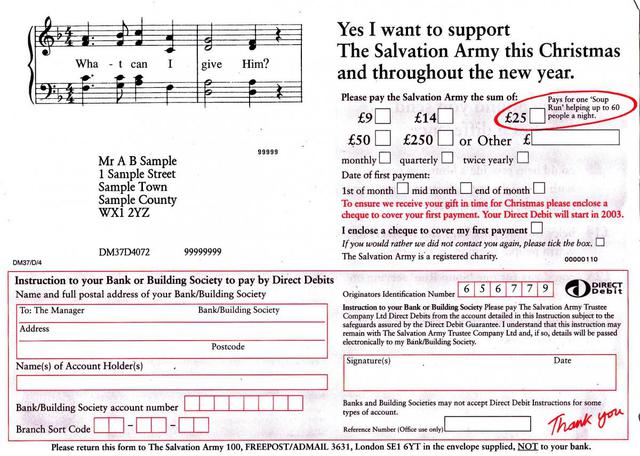

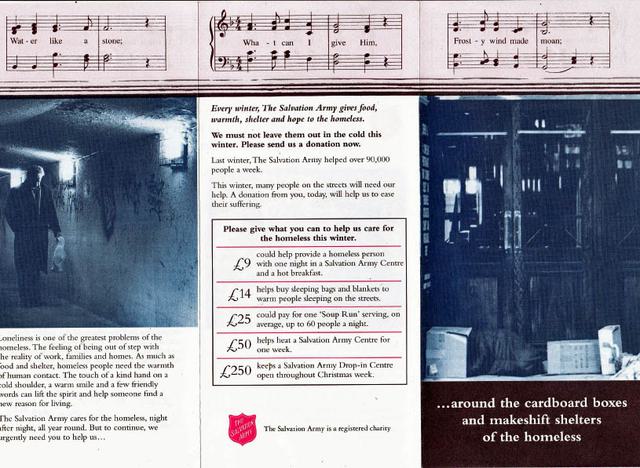

PL: In the Bleak Midwinter is a Christmas carol and you can just imagine a Salvation Army band playing the music and someone in a uniform singing those words. We made the music and words to the carol very much central to the whole letter and used them to tell the story. The aim was to make people think, ‘Ah yes, this is the Army that I know and love, people will be on the street corners at Christmas playing carols, I know all about that’. So the headline is not actually very charity focused, it doesn’t mention the Salvation Army, it doesn’t mention any need, or homelessness, or the problem. It’s just In the Bleak Midwinter, which, just about, passes the ‘so what’ test. There was a lot of repetition all the way through: we’ve got In the Bleak Midwinter in the headline and then in the copy and we say to people start humming this tune now, as you read this.

FB: How important is the Christmas card?

PL: I think that the card is one of the reasons why this campaign worked so well because it is a vicarious action. For a brief moment, when you put that card in the envelope, you can be one of these good people who do this great work without even having to look too deeply at it. You get the feeling that you’ve given something, the feeling that you’ve done something and the feeling you are part of something really rather good.

The Salvation Army hand out a Christmas card and they give pairs of socks on the last run before Christmas. So I certainly thought about the possibility of making the Christmas card more central, sending a Christmas card to someone on the street. I can see the headline now. But I’ve seen it before, other people do it, I wanted this to be different. I wanted this letter to have the dignity that the Salvation Army have. I knew it wasn’t a very traditional charity direct mail pack but, as this was a first for the Salvation Army, they didn’t have to follow a template. Once you do something that works, if you put in labels, or pens, or a survey, they become a template and can become locked in. I wanted them to be locked in instead to who they are, their identity as a charity, not into direct mail trickery. It was a bit of a risk. But we decided that the strength of emotion surrounding the Salvation Army would be strong enough to mitigate that risk. I didn’t want a Christmas card fanfare. The fanfare around the Christmas card in the pack is very minimal: it’s in the PS and it’s on the card but that’s it.

Wisdom would normally suggest that it’s good to connect your supporter to the recipient. But it’s more of a challenge when it comes to being connected to somebody on the street. So here we put the organisation between the supporter and the recipient, because the Army is just so worthy, which everybody knows about, so the pitch is: you give it to us and we’ll do it. We will give them something, a meal, a bed. This again was a departure from what was traditional direct marketing thinking at the time. Usually things work much better if you say you are directly helping this specific person in, say, Africa, and the organisation is merely the means to the end.

It worked very well. We got letters saying, ‘I was going to buy myself a cardigan and I got your letter and decided to give the money to you instead,’ which I just think just sums it up. I think it reached into people’s generosity. I also think the simplicity of the card helped. It’s not lavish and the words make it very clear that you don’t have to do this if you don’t want to.

FB: Do you have a general approach to structuring the letter?

PL: Our job is to raise money, not to educate the public. We’re not attempting to change people’s minds, we’re not trying to say you thought we were this, but actually we’re that. You can educate the public anyway you want, of course, but this is about raising money. When raising money, you present the problem, you present the context, and then a solution. If I have a formula, that’s it. The context is the idea or environment and obviously this is a Christmas appeal, it’s going out in winter, which is the single most important thing about it.

The problem is that people are homeless, they need practical things, soup and warmth and a bed, but they also need somebody to talk to, somebody to pray with them, someone to be human. So it’s not just blankets and soup and beds, it’s a friendly chat, a touch on the shoulders, it’s the human feel and we have to show what is actually happening, because none of the readers is ever going to see it. Unless you are in The Strand at 2 o’clock in the morning, you will never see this. So there’s mystery to it, it’s letting people in on how it all happens in a very practical way.

I think it was important to stay true to the roots of the charity. If you think about it, all charities are actually at their most effective and loud and straightforward in their formative years – think of Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth. But the heritage in the Army is so strong, the uniforms have barely changed; General Booth, the founder, wrote the prayer of dedication that Army members take. Organisations get conned into thinking they’ve got to be new and shiny, like Apple, but they don’t. So we are trying to tap into the deep sense that people have about this organisation.

So that is the folk memory. They haven’t sold War Cry in a pub for about 30 years but that is the sort of thing that people think they remember. So you don’t have to labour the point of we are always here, people have a subconscious knowledge of that.

FB: How does that translate into the letter and the ask?

PL: You have to demonstrate and use people’s feelings about the Salvation Army and the environment – that’s when you hit gold. Christmas comes along every year, homeless people are going to be there all winter, so you’ve got the longevity of the season and the need. It is, to me, the reason some things work better than others, if the need is fairly obvious once it’s pointed out, it did state the bleeding obvious, but it’s only obvious once it’s been stated.

The art is to state the obvious in an imaginative way and allow people to reach an instant and sensible conclusion. By using the environment around you as well as the folk memory about the Salvation Army, things come together, because then you show rather than tell. If you can make the need obvious, then asking is quite easy. But the more oblique it is, the more people have to use their imagination to connect their money to an outcome of some kind. The organisation should look to find something easy, or at least easier.

FB: This is a Christmas appeal. What kind of challenges does that present?

PL: We always tried to run it as late as possible. I always detest Christmas packs in October when the vast majority of the population can’t even think about Christmas yet.

When I do a plan for a client, I get the forecast from the Met Office to see what the weather is likely to be, I look at what day the clocks go back, I look at when the schools break up, I check when the sales start because they are triggers to when Christmas starts creeping up us. I ask myself when do I start feeling Christmassy, when does my mother start feeling Christmassy, when does the old man up the road start feeling Christmassy?

So it’s got to be Christmas in your head before you can write a Christmas appeal, so put up decorations, have cake and shortbread and make it as Christmassy as possible

FB: How do you begin?

PL: Many people say you should start with a donation form, because it sums up what you want people to do. I can’t ever do that because I have no voice, no music in my head, I have no voice that this appeal is going to take, it’s just an instruction. So I need to find a voice: I like lyricism and rhythm and phrasing in copy, I don’t like ugly copy. So I tend to write the first three paragraphs over and over and over again until I find a voice that I’m happy with – a voice that resonates with the organisation that I’m writing for and resonaties with this reader, in my head. So it’s got to match those two things and only when that goes clang do I carry on.

FB: Do you write with a particular donor in mind?

PL: What you write has got to be compelling enough to keep someone who doesn’t want to read it, to keep reading. I write to three or four people. I start off with a very sort of vague idea of Mrs or Mr Donor in my head.

This letter starts with Christina Rossetti’s poem. From the beginning I am assuming that the reader knows the poem because she is educated, went to Sunday School and remembers Christina Rossetti, so it has a historical and an educative resonance. It’s not meant for people who don’t know who Christina Rossetti is. We don’t talk about the carol, we say it’s a poem which again was very deliberate. I’m flattering the reader that she knows that this is a poem.

Also, in terms of the language, I am making it clear that I understand the reader and acknowledge that she, or he, is somebody who can understand and empathise with what I’m saying. In my mind I had an attentive audience that was prepared to listen, that wanted to listen to sermons, for example, perhaps watched documentaries, read the paper – this letter was aimed at people who read. That’s not to say that every charity has the same sort of readership, or even if you’d want to make the same sort of assumption.

FB: Is the letter structured to take into account different types of readers?

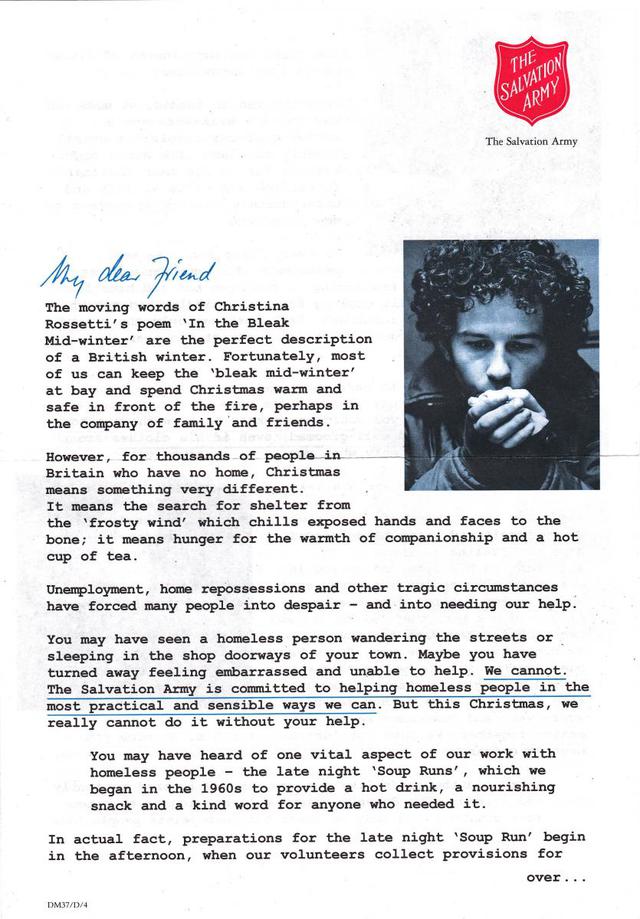

PL: Few people read things in a word-by-word, line-by-line way, your eye actually moves all over the place, it gets anchored and caught by short paragraphs, pictures, bits in bold, underlining and so on. You’re trying to get people interested and then keep them there, by fair or foul means, visually. I tried to take into account the different ways people read and scan by structuring the letter in visual terms, the pictures of homeless people, for example, and the beginnings of each paragraph: vital aspect of our work, late night soup run, each first line has got a quite a harsh word in it. So if all the readers have done by the time they get to the end is look at the pictures and read the first line of three paragraphs, they should still get it.

Also, the way that it looks has to match what is written. So we deliberately chose the old-fashioned courier typeface because it is a simple classic, it’s very unprepossessing, it’s not fancy, but neither are the Salvation Army. So that was very deliberate and the typography in the leaflet matches the typography in the music.

FB: So can you talk me through the letter?

PL: Not many of us can keep bleak midwinter at bay. The frosty wind is there in those first two paragraphs, the phrasing is very poetic, without being flowery and over the top. And then we change in the third paragraph – unemployment, home repossessions, tragic circumstances, many people in despair – you suddenly get this real jarring sensation, it becomes a lot harsher from the earlier style. The aim at the beginning is for people to read something that they want to read and without having the word ‘you’ in it.

Then it becomes more personal. It’s about you the reader. You may have seen a homeless person, maybe you turned away feeling embarrassed, almost certainly you did. The Salvation Army can’t do that, we’re committed. So this emphasises the difference between you, the reader, and us, the Salvation Army, but without making them feel bad about it.

So then it goes on very much in a matter of fact, descriptive way about how the Salvation Army work but, all the way through it, I had the song in my head, the Bleak Midwinter, and I had Good King Wenceslas and bits of the bible floating around. At the end of the first page, for example, it talks about volunteering to collect provisions for the night and turning loaves of sliced bread into sandwiches: there is an echo of the loaves and fishes. There is another echo on the form, to do with gathering winter fuel. So it’s imbued all the way through again and again with this Christianity with a small c.

FB: It’s very bleak, isn’t it?

PL: Yes it is very bleak, it’s meant to be. I want people to read and understand exactly how bleak it can be. I think people get quite scared of bleak, because they worry it’s over-emphasising the problem. But it isn’t, because that is what it’s like if you’ve been there and seen it for yourself – and indeed even if you haven’t.

David Ogilvy always inspired me. In one of his ads, he said that the loudest thing in a Rolls Royce was the ticking of the clock. He knew it because he went and sat in a Rolls Royce; he looked under the engine and he took it apart and saw how it worked. In a similar way I went on the soup run, spent a lot of time with people at the Army, watching how they work. And hopefully that seeped through. You have to absorb experiences as a writer and then let them seep into the words without actually saying: ‘I went on a soup run and this is what I saw’.

The fundamental rule of copywriting is never ask a question to which the answer is no. This letter doesn’t make you shy away, it doesn’t make you cringe, it actually helps you keep on reading because you agree with it. People read it because they feel it’s of interest to them, nothing is more interesting to us than ourselves. And if you tell me something about myself, and I agree with it, I’m going to carry on reading.

FB: Do you go through at the end to make sure that you haven’t put in anything that might stop somebody along the way?

PL: Oh yes. I make sure there is never a sentence or question to which the answer might be no. Even worse than no is so what? The so what test is hugely important and I think every writer should look at every headline and say so what? What does that mean?

FB: The last sentence of this paragraph really connects the two together: we cannot do this without your help. What’s your kind of approach around the whole question of asking?

PL: I think it in this particular instance the idea was to tell the story and then make the ask. The ask is fairly obvious. So we go straight from give us money to a very specific amount, quarterly or regularly, help us do this, £25, £9, £50. It’s very specific and it’s very late on page three. And in between there are things that we hope ‘you haven’t forgotten or you won’t ignore’.

In some letters, I do it in reverse, I start with the need. The need is huge, the funding need is huge and here’s why. It is easier to tell the story first, but only if you’ve got a good story to tell. In this letter we’ve given pictures of homeless people, so the readers can see the need all the way through and, hopefully, by the time they get to the end they’re thinking, ‘what do you want me to do?’

FB: And the next three paragraphs are focused on the soup run: do you want to show all the work that goes into it?

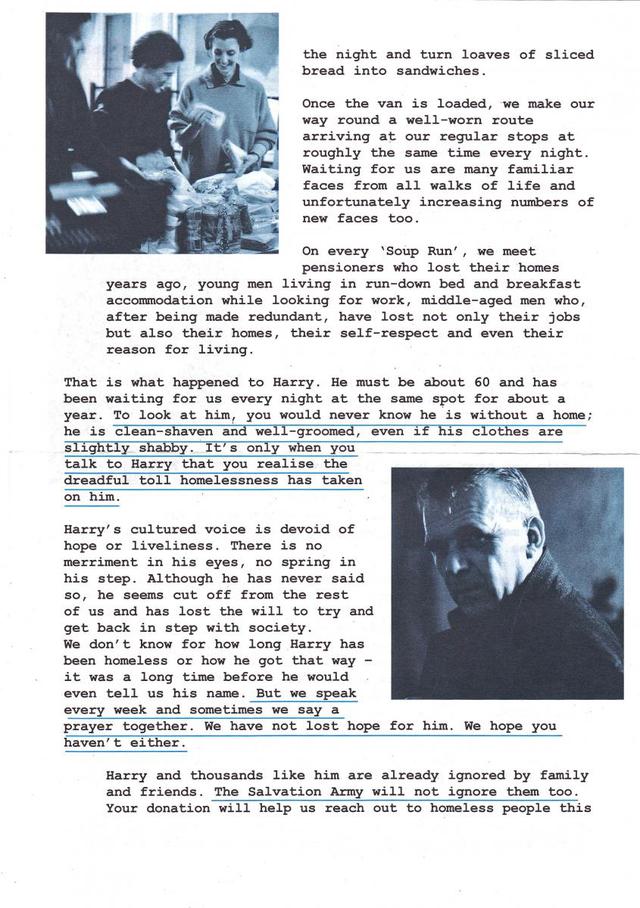

PL: This is a well-worn route. This is what we do, these are the people we’re seeing. I did meet Harry and I tred to give him some dignity, despite the fact he’s in dire straits. I tried to represent eveyone in a way that is authentic, but not off-putting. Some homeless people do have a distinct smell, but I would never write that down. Because, unless you’re Marcel Proust, it’s incredibly hard to write about smell, so it’s best not to. I described people as they are. I was writing, not showing a film, so had to describe in words what people can see, because reading is seeing, so a writer should always keep to what people are doing.

FB: What is the role of the leaflet?

PL: I’m an Ogilvy-educated copywriter and somebody once said to me that the letter motivates and the leaflet educates. So the letter has to do all the motivation, all that emotional and connection stuff. The leaflet is an information piece, it takes a more educational approach. You adopt a different tone, more pragmatic, less emotional. It’s got the unfolding book layout. Whereas a letter is opened up to its full A4, everybody does that automatically, with a leaflet you might not, you might open it the wrong way round, it might be upside down.

Apart from the envelope, you don’t know the order in which people are going to see the contents of the pack. So each piece has to be both part of a whole and to tell the story on its own. I run through a checklist. If I just pick up one piece at random, do I understand what’s going on? Is the tone in keeping with everything else? Then I ask why I’ve got this, what’s it doing there? These are the questions that you should ask yourself when you’re putting things together because each piece of paper costs money to print and to post.

I wanted a leaflet because I wanted as much music as I could, enough pictures to convey the ‘Armyness’ of the whole thing, to show people things that they’ve seen already, people in doorways, and to underline the bleakness.

FB: Tell me about Harry

PL: The automatic perception of a homeless person on the street is a drunk with a dog. I didn’t want a drunk with a dog, even though there are plenty of them. I wanted to surprise people, rather than change their minds. So the reaction you want from that paragraph is: oh, so it’s drunks and dogs as well as people like Harry.

I didn’t want to say that there’s nobody like that at all, but I didn’t want to shine a spotlight on them. As George Orwell said don’t show or tell something that is already a cliché; the drunken man and dog is a homeless cliché, which I didn’t want to use. I wanted to describe somebody who was the antitheses of the cliché, but nevertheless still homeless, and someone that I had actually met.

FB: You say the Salvation Army will not ignore them, this is strong isn’t it?

PL: Yes its very emphatic: we will not do that.

FB: When you talk about your donation, you’re assuming that they’re going to donate?

PL: Yes. I’m assuming two things. One: they know it’s a charity. And two: that the need is self-evident. So the buildings blocks may appear clumsy, there’s a lot of gaps, in contrast to a lot of copywriting which needs to be quite tight. Here, I think, I tried to allow people to draw their own conclusions: you’ve seen the pictures, the bleak midwinter, you’ve got this far, hopefully you understand what we are talking about. The alternative would be to say, for example, the Salvation Army will not ignore them too; we need people like you to support us. If you can give us this, we will do x, y and z, so that’s a tight block.

FB: The language here is quite presumptive

PL: It’s something that you can do only with an organisation like the Army, because their whole ethos is one of generosity. I’m using the readers’ familiarity, the War Cry, the collection boxes, and people asking and receiving. So the assumption is that they know we’re good at what we do, they know their donation will help and that they don’t have to do it themselves. It’s a fine line and I think you can only make this presumption if it’s a really big charity that is renowned for its sincere philanthropy, is known to genuinely help people, has been doing it forever and everybody knows. There are not a lot of charities you can say that about really.

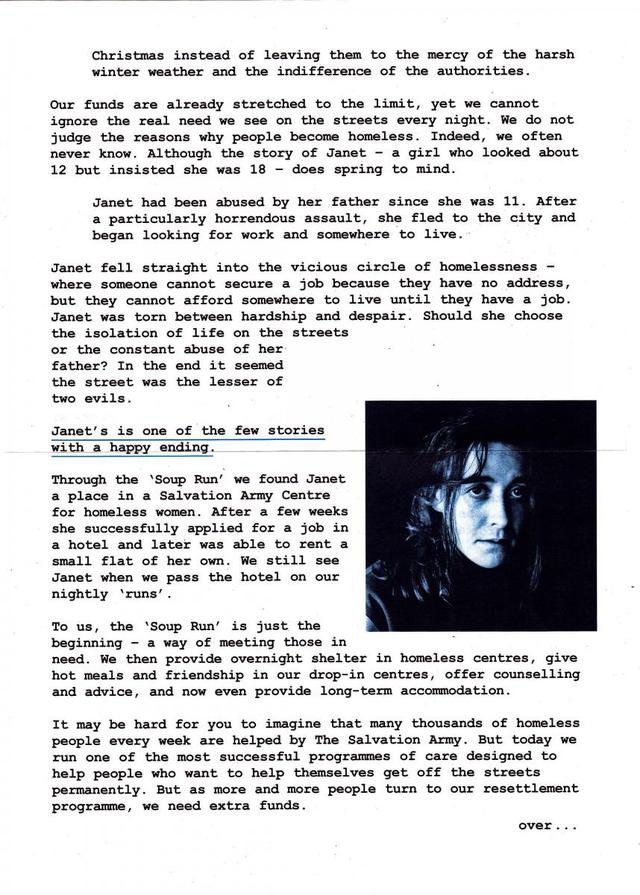

FB: And then you say we do not judge the reasons, that’s really introducing the second case there, the second story? Do you want to talk a little bit about choice of Janet?

PL: Well obviously I wanted a male and female, younger and older. Janet is somebody that I met in the centre for homeless women, I didn’t meet her on the soap run. Basically I wanted to say that homelessness affects all spectrums of society, no one is immune, it could be anybody, this could be your daughter.

FB: And then you move on to Oxford Street

PL: We wanted to show a positive story, but wanted to make a connection back to the soup run, because at his point in the narrative there is a danger that you forget about it, go off at a tangent and start talking about homeless centres. The problem with a lot of case studies is that if you dwell on them for too long, they take you way away from what it is you actually want to talk about. That’s why I wanted to link it right back to the soup run, the soup run is just the beginning.

FB: The last paragraph on the page: it may be hard for you to imagine what’s happening here, again is that a little bit of education?

PL: Again that’s about the scale of people’s experience. How many homeless people have you seen? Have you seen a thousand? No, you’ve seen one or two. So it’s hard to imagine, because you don’t want to. When was the last time you walked past a homeless person in a doorway and thought: he is one of many thousands? You didn’t. So it almost a statement of fact. We didn’t even really need the ‘may be’, but again you can’t be over presumptive and imply what people might do or don’t know.

The Army have a saying that they don’t offer a hand out, but rather a hand up, which is a very nice phrase. We didn’t want to use those words, but that’s the sentiment that we wanted to convey. We don’t just give them a hand out and leave them there, we do carry on and they do come back over and over again for years. Many never come off the street, they don’t want to. They’re not happy but they just can’t imagine anything else.

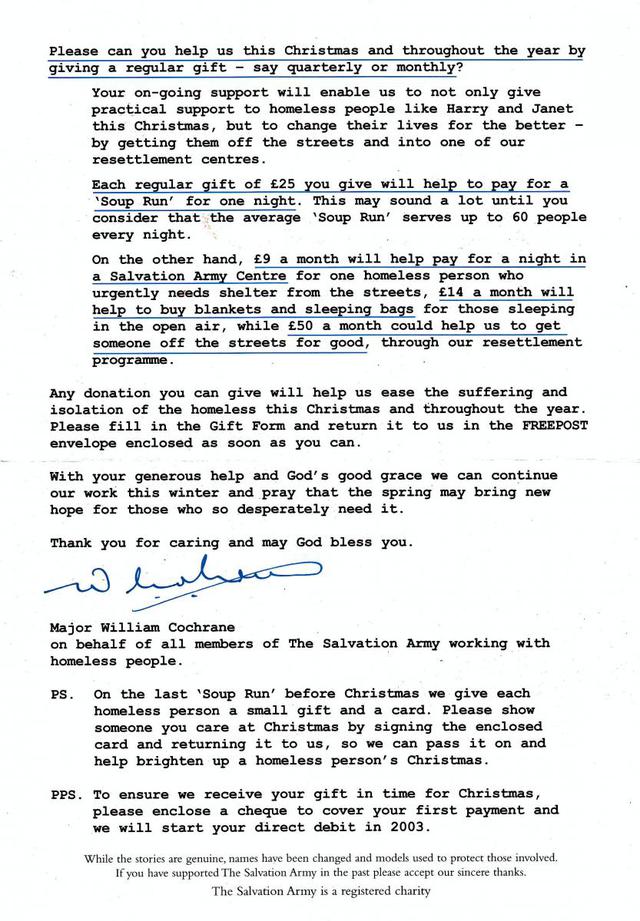

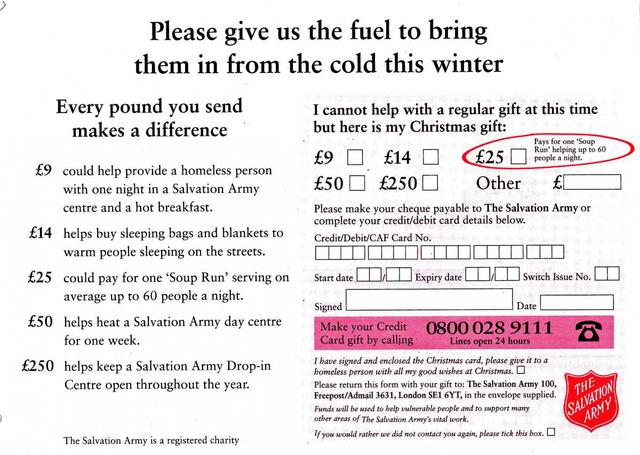

FB: The last page here, really it ups the PS. It’s also explaining what they do with the different sums and also saying that, whatever you do, any donation will help. Do you want to talk a little bit about that?

PL: Well specific is always better than the general and ‘any donation is something’ is not a phrase that trips easily off my tongue for most clients. But with the Salvation Army, someone might have put a quid into a collecting box, in fact probably has, and a pound is a long way from £25 or £9, so you have to be able to attract support from a wide range of means. ‘Every little counts’ is a cliché, but it is actually true in this case, so hopefully we were allowing people to feel good about any donation.

We have no idea really how much people have the mind to give, but we do know that it’s probably relative to what they gave before. But in a cold mailing you haven’t got any hope of even guessing. The Salvation Army was happy with just a pound and, in fact, wrote everyone a thank-you letter however small the amount. But you could ask what is this paragraph doing there? It is actually providing another reason: he’s suffering the isolation of homelessness through the year, so any donation will really do something. It says something about the Salvation Army, of easing suffering and isolation just by being there, just by existing.

FB: Then you say: thank you for caring. I suppose, because they’ve read the letter, have got this far?

PL: You are subconsciously saying if you’ve got this far then obviously you care.

FB: Anything interesting to say about the reply form?

PL: Please give us the fuel: again that echoes the Good King Wenceslas theme and keeps it going, although it is more specific about what we want them to do. But I think the purpose of the form is to be very clear about what is the Army’s work. You can’t tell the story on the form, but you can have echoes back to your story. So what can I give him? The next line of it, which everybody’s familiar with is, what can I give him, poor as I am, if I were a shepherd I would bring a lamb. So you’ve got the warmth in the song in your head and you can have a very pragmatic response: yes I want to support you throughout this Christmas and throughout the New Year and the rest. It’s very workmanlike.