The Help Hollie campaign: how relationship fundraising works at Anthony Nolan

A case history, by John Logan

- Written by

- John Logan

- Added

- April 06, 2017

This case history was originally prepared for the Commission on the Donor Experience and has been specially edited for SOFII.

Background/ summary

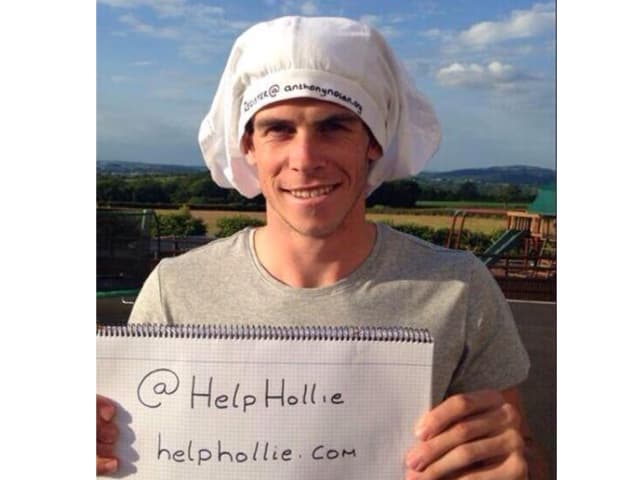

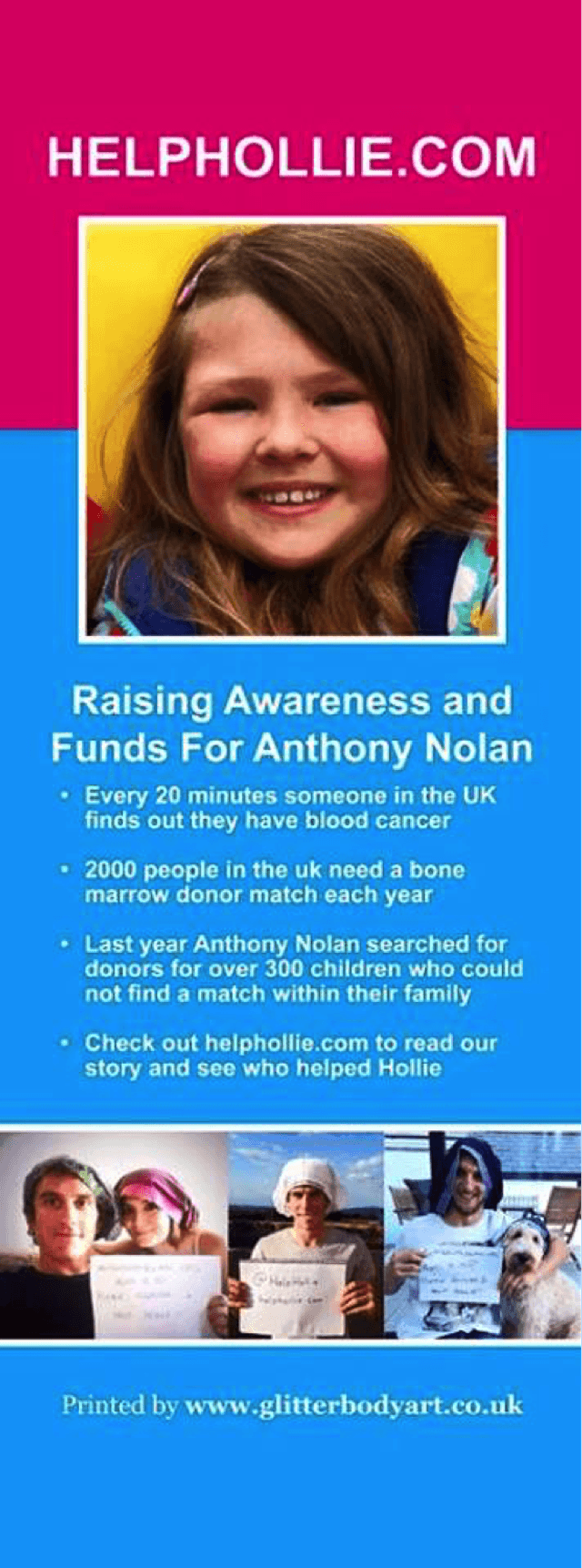

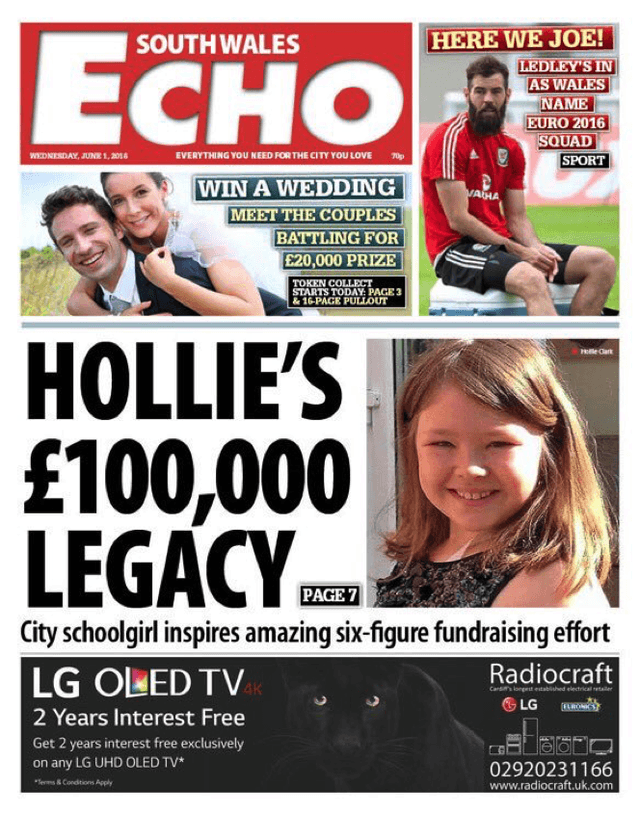

My niece Hollie, aged eight, became unwell in April 2014. The family was told she needed a bone marrow transplant and at the time there was no match for her. We were devastated but we all soon came to realise we needed to find that special person and not sit, hope and wait for a match. A joke from another uncle led to a huge campaign that increased registrations for bone marrow matches in Wales by 2580 per cent in the summer of 2014. At its peak the campaign’s Facebook page had a total reach of 4.6 million and so far £125,000 has been raised for Anthony Nolan.

Hollie found her match and her bone marrow donation took place in July 2014. Sadly, it wasn’t to be successful in the long term and Hollie died in her parents’ arms on 6 November 2014, shortly before her nineth birthday, due to complications.

I am in the unique position of being able to examine this campaign and its effectiveness from the perspective of both a donor and recipient of support from the Anthony Nolan charity, together with being a student on the MsC course in charity management at the Cass Business School’s Centre for Charity Effectiveness in London, which gave me an opportunity to learn about the theory of relationship fundraising. Being based at Anthony Nolan’s HQ for a fieldwork exercise provided an insight into how this charity and its staff put the theory into practice – in my view, incredibly successfully.

From the donor’s perspective

When the family decided to set up a campaign via social media it was impossible to take a view of where it might lead – the only goal at the time was to encourage more and more people to join the stem cell register in the hope of soon finding a match for Hollie to enable her only chance of a life-saving operation.

The first contact that a blood cancer sufferer seeking help and information has with Anthony Nolan charity is usually someone medically qualified from their patient engagement team. Individuals find comfort talking to a ‘name’ so the charity makes particular efforts to begin the relationship by ensuring the same staff member keeps contact initially. Thereby trust and support is built at an early stage.

Support – ownership of the campaign

As the Help Hollie campaign progressed, the family felt incredibly close support from Anthony Nolan, with staff on first-name terms with those involved in the campaign and a continuous supply of promotional materials to help spread awareness of the stem cell register. Above all the Help Hollie campaign was allowed to exist in its own right, i.e. it was not subsumed into the larger ‘marketing machine’ of the professional organisation.

This, as someone who has worked in marketing-related roles at various non-charitable organisations, was particularly gratifying to me as it not only gave freedom to Help Hollie, but crucial extra support at particular times when it would be welcomed through personal support from staff and volunteers at fundraising events. This meant a lot to the family, as Hollie’s mother Laura said in a tweet following the finding of a donor match:

In a short time Anthony Nolan have become part of us. They were there for us and we SURE AS HELL will be there for them. We cannot and will not walk away from them.

The charity clearly appreciates the drive, energy and commitment of supporters and, by offering to support them personally in their fundraising, provides the potential to unlock further donations and awareness on a continual basis.

Legacy campaigning

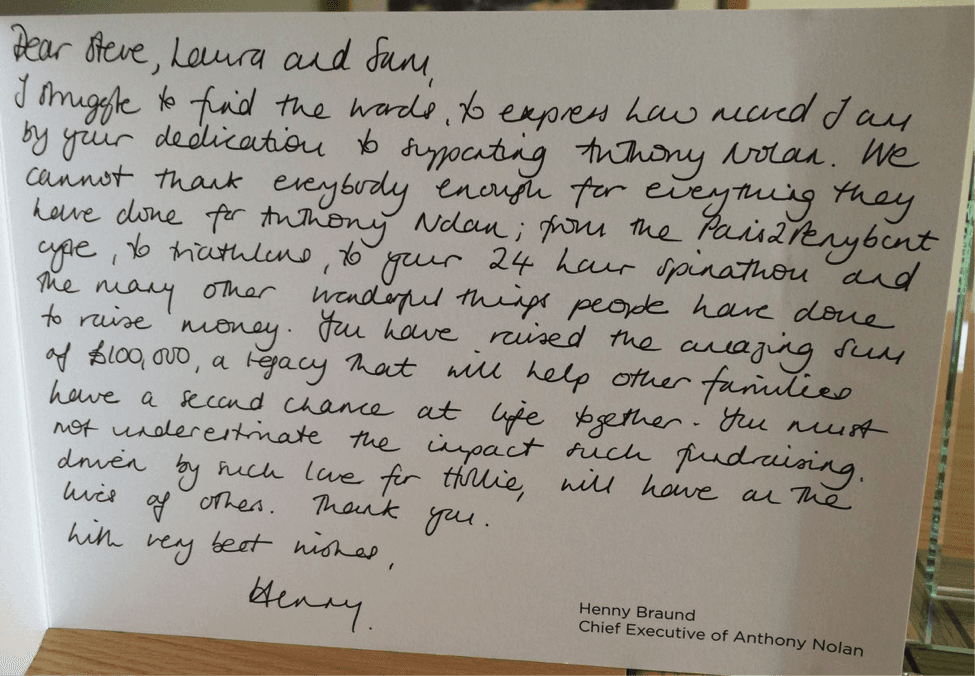

The huge benefit from the personally close and trusting relationship built up over time between Anthony Nolan and the beneficiary family and supporters is seen in legacy campaigning. In the case of Help Hollie – once a bone marrow donor was found and Hollie had her transplant, the fundraising for the charity did not stop. It would have been unthinkable for us to be doing anything other than for Anthony Nolan. When Hollie passed away it actually made the family even more determined to keep her memory alive and the message of hope for others in a similar situation, so the loyalty was strengthened.

Pro-active commitment from supporters is well-recognised within Anthony Nolan and when there is a real-life personal story to tell – a journey of a patient’s search for a donor and post-operation – the messages are easier to convey.

The theory of relationship fundraising in practice – an academic assessment

By participating in activities with the events team at Anthony Nolan’s HQ and in discussions with senior staff members I was able to see the processes and actions of the over-arching relationship marketing and fundraising strategies that have been hugely successful for Anthony Nolan over the past few years. They have set a precedent for other organisations in the sector to maintain long-term relationships with supporters built on mutual trust.

The model of relationship marketing and its progression into the nonprofit sector

For relationship marketing all elements of the marketing mix are important but, according to Professor Ian Bruce (2005), the emphasis in general terms should be on the following:

- Product – must be appropriate from the outset to ensure repeat custom and loyalty.

- Segmentation – the product must be a good fit for the customers’ needs.

- People – staff and volunteers must be trained to ensure quality, and appreciation for supporters, with strategies to maintain relationships and be strong motivators.

At Anthony Nolan the ‘product’ as such could be seen as the gift of life itself – finding a stem cell donor match for a potentially dying patient – so there is no ‘hard sell’ for engagement initially, but there are various wider messages to friends and family of patients to become involved, from signing up to join the register to organising a fundraising event.

From the outset relationship building is vital: creating a strategy for bonding that links patient medical information support closely with communications and fundraising, both for awareness of Anthony Nolan’s own scientific research and the practical needs of finding a stem cell match for waiting recipients. This technique becomes less practical the larger a charity becomes – whilst Cancer Research UK is top of the list of the most recognisable charities, its marketing, communication and fundraising teams in a multi-faceted giant organisation of almost 4000 staff are positioned far removed from its beneficiaries: the individual patients.

In Charity Marketing, Bruce states three critical stages to making the process successful:

- Establishing relationships – to achieve this means prioritising three pre-eminent elements of the marketing mix: product, segmentation and people (staff, volunteers, beneficiaries).

- Strengthening relationships – using marketing research, addressing problems, even encouraging complaints and having a system for service recovery.

- Customer appreciation and recognition – saying thank you, recognising contributions, not just from donors but all stakeholders and strategies such as forming ‘bonds’ with supporters.

At my Anthony Nolan placement in their HQ, and as an external fundraiser at supporter-organised events, I observed these elements working extremely effectively and efficiently. Around 90 per cent of supporters tend to have a personal link to the charity so this makes it easy to begin the relationship engagement process rather than cold calling or outsourcing mass marketing.

Working towards a holistic approach to relationship fundraising

Drucker (1990) espoused the need for the sector to better see donors/supporters as contributors and involve them more; Ken Burnett (2002) – who originally coined the term relationship fundraising in 1992 – took this further and wrote that donors should be seen as co-owners and the sector should be accountable to them. He recommended that relationship fundraising should replace traditional marketing professionals with an emphasis on ‘adapting commercial marketing methods, not simply adopting them.’ (2002, p3)

In mid-2016 Anthony Nolan reorganised internally and the communications, marketing and fundraising department was renamed the engagement division, with Richard Davidson as director of engagement. The growing links between patients, their families and Anthony Nolan during the journey from diagnosis through to the search for a stem cell donor match, then operation to supported recovery had increasingly blurred the traditional communications staged routes; the charity frequently supported awareness campaigns generated and organised from supporters locally themselves, as opposed to always initiating campaigns centrally to be followed, once publicised, by the charity.

Anthony Nolan appreciates the value of close, long-term relationships with patients and their families and capitalises on the lifetime (and beyond) relationships with those it helps. Not only does the supporter feel emotionally valued and rewarded, but feels like seen an equal partner in the cause and becomes inspired to build further on his or her achievements. By making the supporter feel important a basic human need is fulfilled.

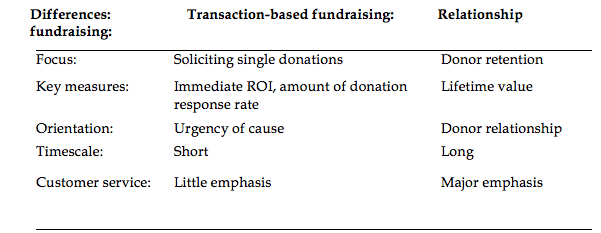

Sargeant (2009, p271) illustrates a comparison of transactional and relational approaches:

Relationship fundraising is predominantly about long-term support for a charity and Anthony Nolan as an organisation exemplifies this model above. Sensitive two-way communication encourages support and satisfaction in fundraising as outcomes can be measured in terms of physical sign-ups to the donor register as well as financial offerings. Traditional transactional approaches are eschewed in favour of communal relationships, with supporters always on first-name terms with staff members akin to extended family.

The work of the charity think tank Rogare at Plymouth University has recently published a major empirical study into relationship fundraising, authored by Sargeant and MacQuillan. For metrics in measuring performance, ROI and customer service levels and donor acquisition are still the dominant indicators of success – as Sargeant stated, ‘I have never met a fundraiser who is remunerated as a result of how satisfied their donors feel.’ (quoted in Cotterill, 2016)

In measuring donor satisfaction right across the sector the Rogare report concludes that a ‘culture of philanthropy’ can eventually be built throughout an organisation, but it would be a seismic shift in the way fundraising is generally approached. By adapting total relationship marketing, i.e. build relationships with all stakeholders (suppliers, media, regulators) Rogare suggests that total relationship fundraising would emerge, echoing the view of relationship marketing as operating at a philosophical level throughout all departments.

This model has proved highly effective for Anthony Nolan – net income almost tripled in six years, rising from £2m to £5.2m after relationship fundraising was actively introduced from 2009 as an overarching policy by Catherine Miles, the former fundraising director.

Regional managers were moved into the London HQ and new staff who sensitively engaged with patients and their families were situated in the same area as other communications and fundraising support teams to ensure that relationships were built in a holistic manner that suited the supporter and the charity.

Miles explained this approach to Cotterill in Civil Society (Feb 2016):

Teams within the organisation work more closely together and there is a large amount of crossover. By giving people options you break down silos and you are not boxing them into just one category of supporter. This develops a deeper, more complex relationship. This approach has had a direct impact on the size and longevity of giving.

Activities to build trust

In terms of community fundraising activity Anthony Nolan’s model appears highly unusual as it does not do cold recruitment and does not stage its own expensive events. As described by employee Lisa Clavering (2014), instead it capitalises on retaining supporters who are empowered to plan their own events, enhancing the experience of supporters and investing in partnering with them, via assigning ‘relationship managers’. This is applying the major-donor relationship in a much wider context and requires dedicated and long-term analysis of supporters with the capacity to raise large amounts of income. As 90 per cent of the active fundraisers tend to have a personal link to the charity, Anthony Nolan can afford to bypass some of the traditional general transactional recruitment communications since awareness has already been raised at a local level – supporters have already appeared.

As there is direct scientific medical research and development carried out by the charity this contributes highly to supporters trusting Anthony Nolan and, of course, there are high trust levels when donors and fundraisers are personally linked to and affected by the cause. Current trends in the sector seek to rebuild trust lost during various high-profile fundraising, governance and marketing scandals, which had huge repercussions culminating in the formation of a new Fundraising Regulator. Anthony Nolan has stated that the charity has no issues with being a paying member and is proud of its track record

Traditionally, patients and their families receiving help and care from Anthony Nolan – a trusted source of vital medical information and guidance – in their search for a stem cell donor wish to give something back in the form of further support through fundraising and awareness-raising activities. As Macmillan et al (2005) concluded by adapting the Morgan and Hunt (1994) corporate model of relationship marketing to a nonprofit setting (see appendix), trust could be measured but communication needs to be supported by shared values and non-opportunistic behaviours.

Communication is therefore crucial and we have suggested three sub-dimensions, namely, informing, listening and staff interaction. Both the qualitative and quantitative results provide evidence to support these sub-dimensions and fundraisers may make use of this finding in their professional role.

The charity secured a unique media collaboration with the media group Trinity Mirror in 2014 – obtaining valuable national and local coverage by presenting case studies and other patient news that journalists would adapt for publication, six annually in national titles and 200 locally. Richard Davison, then communications director at Anthony Nolan said, ’The majority of our media coverage is case study-led, both locally and nationally. Seeing case studies appear in the media is so rewarding because they bring the work of the organisation to life.’ This was another by-product of nurturing relationships with patients and their families – a willingness to trust Anthony Nolan to share their stories in the media.

Anthony Nolan does not engage in door-to-door fundraising but has occasionally used telephone fundraising agencies. The ongoing commitment to the charity from supporters results in far closer and deeper relationships over time, especially where lives are saved. This has resulted in certain fundraising activities being seen as inappropriate or unnecessary – especially where messages can become confused, such as being too old or too young to be signed up for the donor register.

Recommendations

Anthony Nolan is a highly professional, focused charity that makes huge efforts to show that it cares for its supporters and fundraisers, linking its communications and marketing with patient engagement as part of its successful relationship fundraising long-term strategy. This ensures it is not as ‘corporate’ as some of the larger charities can appear to be and can truly empower supporters who are trusted to pursue their own campaigns. Sixty per cent of the charity’s supporters repeat their fundraising activity or take on a subsequent one, which shows that its approach does build long-term relationships.

In achieving the ‘holy grail’ of total relationship marketing, Anthony Nolan has carefully evolved this strategy and has progressed since 2009 from lower-return, small regional community events onto higher-return targeted account management for individuals and groups raising money locally, which has more than doubled its net income. Whilst this strategy can be seen to be working well, there are more options that the charity may choose to take in building on its successful activities.

Conclusion

The relationship fundraising model works highly effectively in nurturing and developing a mutual relationship of trust between supporters and Anthony Nolan. Given the recent crises in the sector involving various household name charities, particularly in the area of direct marketing, it is perhaps a model that other charities should seek to emulate. One possible drawback might be the levels of commitment by individual staff necessary to nurture ever-growing numbers of supporters, especially where they may leave for jobs elsewhere and how this affects relationships. For now, I was informed that the numbers are manageable within the charity at its present size.

Where there is a fast-moving results-driven culture in organisations, whether commercial or nonprofit, the need to hit income targets can pressure fundraisers into gaining quick wins at the expense of nurturing long-term relationships with supporters. The recent conclusions of the PACAC (the UK Parliament’s Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee) into the various charity scandals of 2015, that the failure of trustees to fulfil their responsibilities had caused them, highlights the need for organisations to examine their fundraising methods and their relationships with supporters through their communications.

For the academic community there would appear to be a need for more studies undertaken to examine theories behind community fundraising such as at Anthony Nolan and how best to manage the psychological contract, especially with younger supporters who live their experiences publicly via social media. Only with more empirical data can sustainability, regular giving and predictability in fundraising via long term, nurtured supporter relationships be a realistic model for more charities (and in particular their boards) to base their strategies around.

We need to entirely rethink how we engage with donors. We have to get away from thinking that fundraising is all about asking for money – it’s not. If you start at that point you won’t get it and you won’t deserve it. You have to give people a reason to give. Charities need to genuinely put the donors at the heart of their fundraising and make the experience of giving a positive one. If that can happen then I think fundraising in the long-term will flourish.

Ken Burnett, in Cotterill, Feb 2016

References:

Andreasen, A. and Kotler, P. (2014) ‘Strategic Marketing for Non-Profit Organisations’, Seventh

Edition, Pearson, Harlow

Boenigk, S. and Scherhag, C. (2014), ‘Effects of Donor Priority Strategy on Relationship

Fundraising Outcomes,’ Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 24: 307–336.

Bruce, I. (2005) ‘Charity Marketing – Delivering Income, Services and Campaigns’, ICSA, London

Burnett, K., (2002), Relationship fundraising: a donor-based approach to the business of raising money, 2nd edn, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, USA. The White Lion Press.

Christopher, M. et al (2002) ‘Relationship Marketing – Creating Stakeholder Value’, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford

Clavering, L. (2016) ‘ Community Action: the rise of Anthony Nolan’s community fundraising programme,’ Civil Society.co.uk, (accessed 9/2/17)

Cotterrill, S. (2016) ‘Love me, love me not: Can relationship fundraising redeem the sector?’, Civil Society.co.uk, (accessed 9/2/17)

Drucker, P. (1990), ‘Managing the non-profit organization: Practices and Principles,’

Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

Maple, P. (2013), ‘Marketing Strategy for Effective Fundraising,’ Second Edition, DSC, London

Sergeant, A. (2009), ‘Marketing Management for Nonprofit Organizations’, Third Edition, OUP, Oxford

Macmillan, K., Money, K., Money, A., Downing, S., (2005) ‘Relationship marketing in the not- for-profit sector: an extension and application of the commitment–trust theory’, Journal of Business Research, Volume 58, Issue 6, June 2005, Pages 806-818

Miles, C. and Haw, A. (2013) ‘Fundraising and Finance – Natural Partners’, Civil Society, 14

Jan 2013 Civilscoiety.co.uk (accessed 9/2/17)

Rawstrone, A., (2014) ‘At Work: Communications - Interview - 'Case studies bring our work to life'. Third Sector, pp. 20. (accessed 9/2/17)

Ricketts, A.(2016) ‘More people leaving charitable bequests than ever’,Third Sector, 8th Sept 2016 (accessed 9/2/17)

Media References:

The beginning of the campaign:

On Twitter, the About page and on Facebook.

TV coverage:

Local TV news. Also on the BBC.

The campaign progresses:

Reported on The Telegraph and the Dailystar.

A match if found.

Reported on The Guardian. The Telegraph. The Western Telegraph. The West Morland Gazette.

Hollie’s passing – but campaign for Anthony Nolan continues:

Legacy successes:

Anthony Nolan news: