When fundraising collapsed – are we ready for a new era of responsible fundraising?

As we enter another year in fundraising, Giles Pegram is pausing to look back. In this article, he reflects on some important moments in his time as a fundraiser – from 1983 to the present. Giles also refers to the lessons found in the Commission on the Donor Experience and offers fundraisers ten tips that he believes will help you usher in a new era of responsible fundraising.

- Written by

- Giles Pegram CBE

- Added

- January 10, 2024

In 2015, the fundraising profession faced an existential crisis. Those of you who have joined our profession in the last eight years may not be fully aware of it, or its consequences. This is for you. It’s also for you even if you’ve been actively fundraising for decades.

Fundraising, before 1983

For as long as there is history, written down or told round the campfire, most human beings are hard-wired to want to give help to those less fortunate. There are countless examples in the Bible. I know it less well, but there is much also in the Quran. There is a lot written down about the re-building of Troyes Cathedral in the fourteenth century. It makes fascinating reading. Again, at its heart, is the concept of philanthropy.

When I started fundraising, in 1960, it was that concept of philanthropy that drove me, though of course I didn’t comprehend it at the time. The rest of my life has, essentially, been devoted to fundraising, i.e., tapping into that philanthropy.

1983 – forty years’ ago – fundraising becomes a profession

In 1983, I had been appeals director of the NSPCC for four years. In those four years I achieved quite a bit, but:

- Fundraising was not in any way regarded as a ‘profession’. Most appeals directors were retired rear-admirals.

- There was no forum where fundraisers met and exchanged successes, failures and ideas.

- I brought the appeals directors of the other big five children’s charities together over lunch, to exchange activities and results. But it was surreptitious. We would have been sacked if it had become known that we were exchanging our trade secrets with other charities.

- Fundraisers worked in their own charity bubble.

So, in 1983, a group of us set up the Institute of Fundraising (now the Chartered Institute of Fundraising). To transform the status quo; to provide fora for fundraisers to meet; an annual convention; to turn fundraising into a ‘profession’, with fundraisers as ‘professionals’; to provide training in best practice.

Then, fundraisers did start meeting each other, the annual convention was founded, and fundraising training was started from scratch. None of these existed before 1983.

In that context, in 1992, SOFII founder Ken Burnett published the first edition of Relationship Fundraising. It said, very clearly, that fundraising should be about relationships, not transactions. It was the definitive and influential handbook, on every fundraiser’s bookshelf. We all called ourselves ‘relationship fundraisers’.

The downside of professionalism

But ‘professionalism’ is a double-edged sword.

In some cases fundraising became a smooth, slick operation. The fundraising process had become mechanised; fundraising departments had become machines. We fundraised at people. Fundraising had become an activity to raise money, not a vehicle to connect donor and cause.

There was a fundamental contradiction. Even though relationships with donors should be long term, fundraisers were judged by monthly performance against budget. Each year, department by department, we set the annual budget. And even a monthly cash flow. Income was monitored monthly, with variances needing to be explained.

The very walls of our offices whispered ‘budgets’.

Even volunteers became cogs in the machine. If there was a shortfall against budget, we would ask volunteers to organise another event. Never mind the volunteer experience. Even volunteers were a means to an end.

It was short term over long term. You spent ‘x’ and you raised ‘y’. You spent ‘x’ and you raised more than ‘y’. That was regarded as ‘better’. All became subsumed by arbitrary year end targets.

Here’s just one example.

We discovered that using the phone was a good way to inspire donors to give. Most charities didn’t want to set up their own call centres, and so phoning donors was outsourced to telephone fundraising agencies. But often, these agencies would be appointed by relatively junior fundraising staff, and were judged simply on ‘performance’; i.e., money raised. So, agency staff put relentless pressure on donors. Successes were celebrated within the agency and chalked up on a blackboard. And of course they were not committed to any particular charity. They would be phoning to raise money for one charity one day: another the next.

2015 – the fundraising edifice collapsed

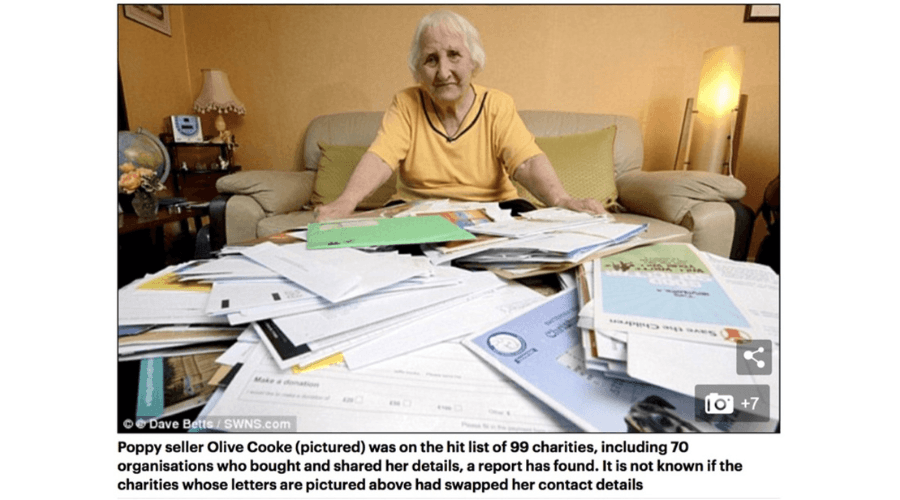

A 93-year-old woman, Olive Cooke, took her own life in 2015. She was receiving 3,000 mailings from charities in a year, as well as many phone calls. According to a friend quoted in The Guardian newspaper, ‘They would phone,’ he said, ‘and she would have a job to put the phone down again. She felt guilty she couldn’t give in the same way she wanted to give. She felt tormented.’

Bad fundraising practice, such as the telephone fundraising I talked about above, was exposed. Telephone fundraising agencies went bust. There was relentless exposure of widespread unacceptable fundraising practices across the country as, week after week, fresh scandals were revealed in the national media, and locally too. The press enjoyed a feeding frenzy. For the full story see here.

Of course, the tabloid media sensationalised it, as they would, and made it very personal, knowing that’s what their readers would want. Stories of individual people. But we should have anticipated this, surely?

An appeals director of a major charity, a good friend over decades and of unimpeachable character, was photographed with his wife, on holiday, enjoying a glass of sparkling wine. That was printed as an example of how donors’ hard-earned money was being spent on a luxury lifestyle. Grossly unfair. But expected of the Daily Mail newspaper. It’s what it does.

The British people, used to allowing charities considerable latitude because they were ‘good causes’, rose up unhesitatingly to condemn these outrages wholesale. Everyone could chip in their personal experiences of similar injustices, which they did enthusiastically on every phone-in programme or online article that offered the opportunity for posting comment.

The British Broadcasting Company (BBC) published a poll revealing that 52 per cent of donors who give regularly to charity by standing order or direct debit feel ‘pressurised’ by fundraisers into increasing their donations.

There was a crisis of confidence. Much-respected charities suffered severe reputational damage.

Despite the exaggerations appearing regularly in the tabloid press, the fundraising profession as a whole could have welcomed this exposure of bad practice, said sorry and taken the opportunity to launch a co-ordinated root-and-branch review of all fundraising practice, with an assurance that things would now be put right.

But we didn’t. Our entire sector went on the defensive, tried to justify our fundraising and vilified the Daily Mail, Sun and others. In short, within the fundraising world, it was the sensationalising media that was the villain of the piece, not we fundraisers. We were their victims.

The Commission on the Donor Experience

Ken Burnett and I, friends and colleagues for many decades, both believed that something really significant should be done, by us fundraisers. We wanted to ensure that all fundraisers were following some common view of best practice, that could be signed up to by fundraisers everywhere. Ken suggested we should set up a commission on the donor experience.

In the largest mobilisation of volunteers in our sector ever, around 2,000 individuals registered with, contributed content to, supported projects or otherwise assisted the specially formed the Commission on the Donor Experience (CDE). It was an initiative set up directly in the wake of the scandal to define and document the comprehensive culture change that was called for, if fundraising was to put its house in order. The CDE’s 28 detailed reports are all available in full, here on SOFII, as is Ken’s essential summary document, the ‘6Ps’.

That takes us to 2017, when the CDE’s final report, with its recommendations and guidance to fundraisers, was presented at the CIOF’s annual general meeting (AGM). It received an overwhelmingly positive reception.

Having reviewed Ken’s ‘6Ps’, I actually found ten important principles which I believe are a useful tool for fundraisers who are new to the sector, or who want to renew their knowledge of the much-needed basics.

The essence of the Commission on the Donor Experience’s conclusions

1. Anyone who gets a great experience when supporting a charity will, over their lifetime, give significantly more than someone who doesn’t.

So the donor-centred approach will lead to increased net income for good causes, at least in the medium to long-term. If giving is seen to be a rewarding, enjoyable experience people will do more of it. If it isn’t, people will soon stop.

2. While fundraisers should exemplify both passionate commitment to their cause and appropriate professional standards, passionate belief in the cause is usually more valued by donors than technique or slick professionalism.

Though they greatly value competence and commitment, many donors are suspicious of business practices and overt commercialism from the charities they support. Many prefer to see a different, more distinctive, more obviously values-led approach. Donors generally will prize passionate belief in the cause ahead of technical abilities.

Openness and transparency should be watchwords that guide our accountability to all supporters.

3. Fundraising should be measured long term, not just on immediate returns.

Fundraisers should be judged at least as much by longer-term, more donor-friendly criteria rather than just by income raised now.

Fundraising is an investment, not a cost, so investment in fundraising should be encouraged. Lack of appropriate investment in the donor experience and donor relationship development should be seen as irresponsible if available funds are deployed elsewhere in short–term, less productive and less crucial activities.

4. Integrity and consideration will underpin each and every contact with a donor.

Fundraisers should always do the right thing by donors, always treating them with respect and consideration in everything from the language fundraisers use to the style and content of each contact.

5. Donors must be in the ‘driving seat’.

Giving is voluntary. Every donor should be in consistent, effective control of his or her personal, individual relationship with the causes he or she supports.

We will provide consistently inspirational and effective communications to spread the joy and sense of fulfilment and achievement that can come from giving to a great cause.

And we’ll offer donors the chance to choose what they hear about from us, how often and when.

6. Every communication with donors should leave them feeling better about their support after the communication than before it.

So, inspiration rather than persuasion. Fundraisers will perfect their storytelling skills in a new approach to impact measurement, accountability and reporting.

We are proud of our supporters and treasure their role in making possible everything our charity achieves. Our supporters – donors who give money and volunteers who give their time and talent – will always be at the heart of our thinking, top of our concerns. We see our supporters as partners in making our mission achievable, so as much as practical we’ll seek to directly link our supporters with our work.

7. All supporters will be treated equally at all times with care, consideration, integrity and respect.

There will be no coercion, pressure or undue persuasion and the donor’s right to say no will be cheerfully and immediately accepted.

8. Whenever practical we will be available to our donors, eager to listen to what they have to say and to take action appropriately.

Our supporters will deal with named people they can put a face to and who are easy to contact in ways and at times designed to suit them.

9. Our charity will report on the differences donors make with honesty, clarity, precision and impressive promptness.

Our mantra will be ‘the truth, told well’ and we’ll aim to be famous for fast, frequent, fabulous feedback (the 5Fs).

10. ‘Fundraising isn’t about money. It’s about important work that needs doing. If you start by asking for money, you won’t get it and you won’t deserve it.’ – Harold Sumption – founder, The Resource Alliance

Asking for money should be the last thing you do after communicating appropriate information and inspiration. By then the pressure should be off, the outcome a foregone conclusion, decided by the donor.

After 2017 – where are we now?

Has fundraising changed? There is much evidence to suggest it has. And, increasingly, the words ‘donor experience’ and ‘supporter experience’ are appearing in job titles. That must be a sign of progress.

But, too often when there’s a catastrophe in commerce, organisations or government, we hear the words, ‘We have taken steps to ensure that this can never happen again’. Yet how could that be possible? It could, of course, happen again.

We fundraisers must never forget 2015, nor move away from Ken’s thinking, above. The days of little old ladies with flag day collection boxes are (very sadly, in my honest opinion) gone. Online fundraising and social media mean that one stupid but disasterous mistake will be all over X (formerly known as Twitter) and other social media sites, within the hour.

Are we, as a profession, prepared?

Or are we not? We need to be.