The Olive Cooke story

How the suicide of a generous, inspirational poppy-seller is leading to transformational cultural change in fundraising practices worldwide.

- Written by

- Ken Burnett

- Added

- January 14, 2021

The fundraising sector could have reacted better to the media storm that followed the tragic death of 92-year-old Mrs Olive Cooke in 2015. But after several years of soul-searching, real and important change has begun. This article revisits the story and delves into what we as a sector can learn.

Introduction

Anyone even remotely connected with fundraising in the UK will know the name of Mrs Olive Cooke only too well. It’s a name synonymous with scandal and disgrace for fundraisers since 2015, when the story alleging that charity fundraisers had hounded Mrs Cooke to her suicide hit the front pages of Britain’s tabloid press. An avalanche of indiscriminate appeals for donations, so the papers claimed, had led her to take her own life. Irrespective of the reality behind the accusation, this was far from fundraising’s finest hour. The allegation prompted the relentless exposure of widespread unacceptable fundraising practices across the country as, week after week, fresh scandals were revealed. As Britain’s tabloid press sharpened their pens and fixed their sights firmly on fundraisers, the UK charity sector battened down the hatches and prepared for a media assault unlike anything ever seen before.

Mrs Olive Cooke was 92 years old when she died after jumping from the Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol, the city where she had collected money for the Royal British Legion for 76 years. Her death sparked a furore in the British media that set off a sustained surge of press attacks criticising then current UK fundraising practices.

Olive Cooke began selling poppies in 1938, when she was 16, having been inspired by her father, a veteran of the Gallipoli campaign in the first world war. After her husband, a sailor in the Royal Navy, was killed in Italy in 1943, leaving her a widow at the age of 21, she devoted herself even more passionately to her charity efforts.

Mrs Cooke became a familiar face in Bristol in the runup to Remembrance Day. She sold an estimated 30,000 poppies and made direct debit charity donations to more than 20 good causes. Then, later, she cancelled these. According to a friend quoted in The Guardian newspaper, this prompted an increase in the number of calls from charities asking for her help. ‘They would phone,’ he claimed, ‘and she would have a job to put the phone down again. She felt guilty she couldn’t give in the same way she wanted to give. She felt tormented.’

The dark, dubious underbelly of charitable giving

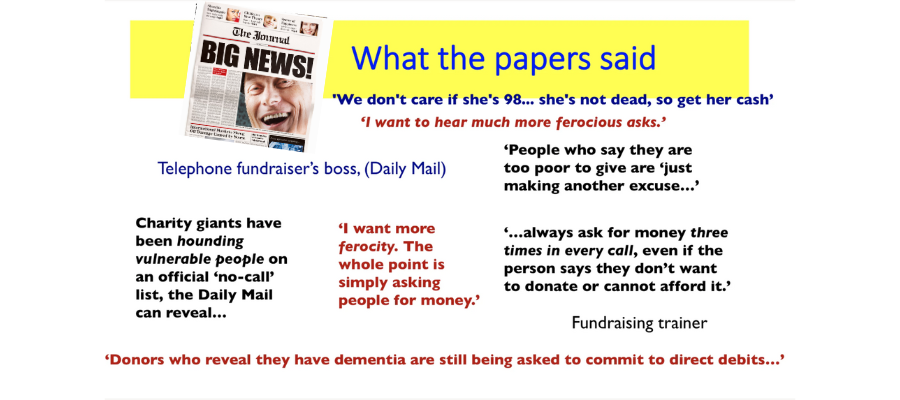

Sections of the media quickly escalated the story to expose every instance they could find of inappropriate public fundraising, focusing particularly on the deliberate targeting of generous, vulnerable or elderly donors through persistent repeat approaches, profiling, wealth screening, over-mailing, address swapping and other claimed transgressions. Press persistence in uncovering the sordid detail may seem a reasonable response to a serious, easily imaginable problem. But in Britain at the time, quite widely, it wasn’t seen like that. To the tabloid readership the story was presented as in the public interest – the press lifting a veil on the dark, dubious underbelly of charitable giving – but back in 2015 many within the UK voluntary sector saw it as a coordinated anti-fundraising campaign led by the media and fed by right-wing political voices opposed to any kind of radical political campaigning from mainly ‘leftist’ charities.

The story had moved on and shown it had ‘legs’. The gentlemen and gentle women of the press had set their sights on charity fundraisers, amassing and exposing evidence of widespread and systemic inappropriate behaviours.

Later it emerged that Mrs Cooke’s family did not believe charity fundraising had contributed significantly to her death. She’d long suffered from depression and had other issues that led her to end her life as she did. To some national newspapers this revelation was taken as almost incidental. The story had moved on and shown it had ‘legs’. The gentlemen and gentle women of the press had set their sights on charity fundraisers, amassing and exposing evidence of widespread and systemic inappropriate behaviours. Malpractices, misconduct and manipulations were all too easy to track down, illustrate and sensationalise, so the shock horror exposés kept on coming. Journalists were planted in call centres and face-to-face teams across the land to catalogue the horrors within. It may have subsequently turned out that at least some of the worst allegations were untrue, or were exaggerated to make a better story, but the seeds of disaster for charity fundraising had been sown. Though previously rarely even whispered, allegations of greedy charities targeting and aggressively pursuing elderly and vulnerable donors to secure gifts in underhand, unacceptable ways were now plastered across the nation’s front pages with relentless regularity. The British people, used to allowing charities considerable latitude because they were ‘good causes’, rose up unhesitatingly to condemn these outrages wholesale. Everyone could chip in their personal experiences of similar iniquities, which they did enthusiastically on every phone-in programme or online article that offered the opportunity for posting comment. Similarly shocking stories were dissected disapprovingly on the public’s favourite TV and radio chat shows. The lambasting of fundraisers reached fever-pitch.

The shaky public defence of fundraising

Consequently, fundraising campaigns were cancelled, suppliers were dropped and in many organisations donor acquisition and development were put on hold. So damning was the flood of media exposures and so negative was its analysis and public reactions that many young people decided fundraising was not the right career for them, so talented young people left the sector in droves. The majority though pulled back on their fundraising, hunkered down and hoped it would go away. It didn’t. For at least two long years, variations on the theme would bubble up with depressing regularity. From time to time, they still do. This hasn’t gone away.

…while a few individual voices were raised to defend fundraising, a coordinated response from the sector appeared to be absent.

Something needed to be done. Yet, while a few individual voices were raised to defend fundraising, a coordinated response from the sector appeared to be absent. Individual fundraising leaders, privately critical of the ongoing vilification of their activities, were reluctant to risk personal exposure in the media. Many organisations forbade their fundraisers from speaking to the press for fear of the negative publicity that might ensue. This was understandable in individual cases as some eminent fundraising figures had already had their personal details plastered over the more sensational tabloids, with several suffering highly personal pillorying for their private lives, their salary, how they socialise and the value of the homes they were living in.

A personal anecdote from this period illustrates the febrile atmosphere of the time. In October 2015, just after publication of the UK Government-commissioned Etherington Review (hastily convened to recommend regulatory changes in response to the public outcry), I was asked to be a temporary spokesperson for NCVO – the National Council of Voluntary Organisations, of which Sir Stuart Etherington was CEO – as they didn’t have a fundraiser on their staff. Thus I found myself invited to partake in several radio and TV interviews focussing on the fundraising crisis. One of these was as part of a panel discussion on the BBC2 flagship morning television news and current affairs programme The Victoria Derbyshire Show (see short video clip here).

‘Surely,’ I said, ‘you could have got someone with more recent experience than I?’. ‘We tried’, the normally unflappable Joanna responded glumly. ‘No current fundraising leader would agree to speak to us, on air.’

To coincide with the launch of the Etherington Review the BBC had just published a poll revealing that 52 per cent of donors who give regularly to charity by standing order or direct debit feel ‘pressurised’ by fundraisers into increasing their donations. As we waited for our segment of the programme to go ‘live’ on air I saw on a monitor in front of me a caption beneath my image that described me as, ‘former director of fundraising, ActionAid’. I turned to my interviewer, Joanna Gosling, exclaiming, ‘ahem…that was in 1984, Joanna, more than 30 years ago. Surely,’ I ventured, ‘you could have got someone with more recent experience than I?’. ‘We tried’, the normally unflappable Joanna responded glumly. ‘No current fundraising leader would agree to speak to us, on air.’ Chastened, I realised that I’d been a long way from first choice for this programme. But, more seriously, the situation suggested something of a problem for our sector, as so few folk in fundraising organisations seemed willing to publicly defend what fundraisers do.

Why all this still matters, six years on

Two years of sustained media attacks on dodgy fundraising practices followed and the story’s never really gone away. The woes of fundraisers may not feature quite so often on Britain’s front pages now but that’s just because other calamities such as Brexit, Covid-19, royal disharmony and our political leaders’ staggering ineptitude have of late kept our comparatively minor transgressions from the spotlight.

So, a sad tale of a horrid time for fundraisers. But all this is coming up to six years ago now. What are the lessons that remain and why is this story still of paramount significance for fundraisers everywhere, today?

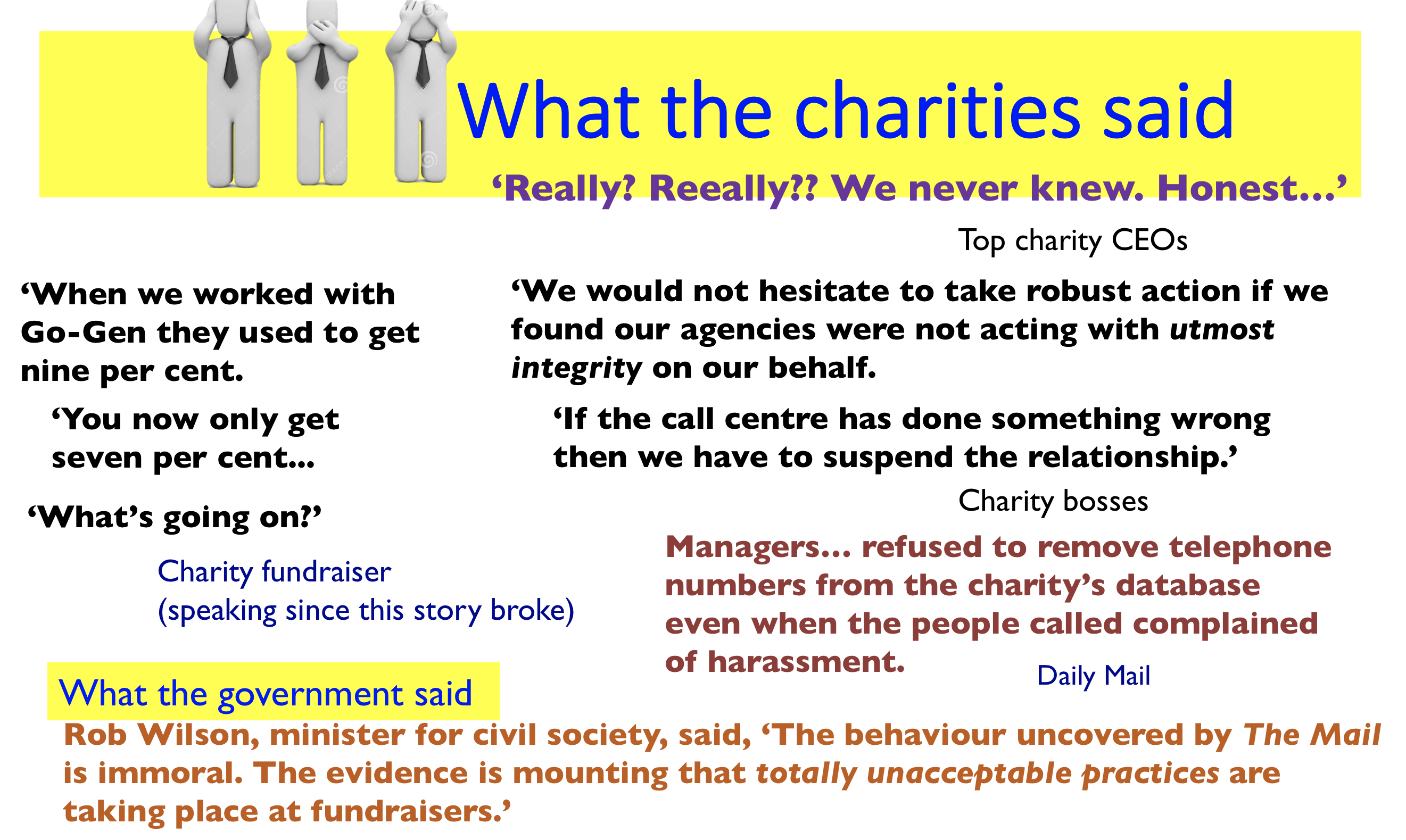

UK fundraising’s response to the crisis sparked by Mrs Cooke’s death could easily be characterised as too little, too late, too lightweight. CEOs of leading charities, called before Parliament to explain what had gone wrong, sought to justify themselves by blaming rogue suppliers who, they assured, would now be sacked. This was perhaps the lowest point for our sector, though that abdication of responsibility was never likely to stick. The client is always in control, anything else would be an abject failure of duty. If they didn’t know what was being done in their name, they were culpable and should have been fired. If they had known what was going on in their name yet still did nothing to stop it, they should have been fired also. Many supplier companies did close their doors as a direct result of lost orders and shelved campaigns, though for the most part they’d just been doing what their clients had demanded. Corners had clearly been cut, but only with the tacit approval of their charity clients as they demanded ever-lower acquisition cost per new donor. Many good fundraisers lost their jobs at this time, along with, it has to be said, some really bad ones too.

A new regulator was put in place, imposed by Government. The overseeing and regulation of fundraising was revised and tightened, effectively removing self-regulation for ever and assuring ongoing external supervision that fundraisers had hitherto firmly resisted but now could no longer avoid. General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was then rising fast up the fundraiser’s agenda and there was much wringing of hands and talk of reduced incomes and ‘managing decline’. Trust and confidence in charities was reportedly at an all-time low. Yet to the surprise of many the changes designed to protect the vulnerable public proved manageable, even sensible. The realisation spread that, after all, it’s in the interests of fundraisers to ensure that donors are protected and spared undue pressure or any hint of cajoling. Soon everyone was asserting that they’d always shunned anything even approaching hard selling or aggressive persuasion from fundraisers. It was, all averred, simply bad fundraising, harmful for both the donor and the charity. No one was denying that, at the behest of many fundraising charities, the exposed bad behaviours had been going on far too much for far too long. It just wasn’t them. Honest. Uncomfortable though it was, it gradually began to dawn that, really, the press had done fundraising a favour by drawing attention to our sector’s shortcomings. Now, no more hand-wringing, the priority had to shift. Fundraisers urgently needed to show that they had listened and learned and were going to put this right. It became blindingly, brilliantly clear – our sector now needs to deliver a new era of responsible fundraising.

The largest mobilisation of volunteers in our sector, ever

Which, of course, is what the Chartered Institute of Fundraising (CIoF)’s Supporter Experience Project is all about. As if to encourage us, public trust in charities seemingly rebounded surprisingly quickly, though it was appreciated that this perhaps was more due to the urgency and appeal of our causes than thanks to the actions of our fundraisers.

In the largest mobilisation of volunteers in our sector ever, around 2,000 individuals registered with, contributed content to, supported projects or otherwise assisted the specially formed Commission on the Donor Experience (CDE), an initiative set up directly in the wake of the scandal to define and document the comprehensive culture change that was called for, if fundraising was to put its house in order. The CDE’s 28 detailed reports are all available on SOFII now, as is their summary document, the 6Ps, and the shorthand simplification of key points, the 32 Lightbulb Moments. Once CDE had completed its time-limited task CIoF’s Supporter Experience Project picked up the mantle, to catalyse and ensure delivery of the needed changes.

In life Olive Cooke was many things. She was a humanitarian who, quite simply, would have done anything for anybody. She supported many charities as a volunteer, through direct debits, with donations and in other ways. And she was one of the most successful poppy-sellers ever for the Royal British Legion. Because of her exemplary life and unhappy death Olive Cooke inadvertently became a symbol for something else – charities’ deliberate exploitation of potentially vulnerable, mainly elderly donors, to pressurise them into giving ever more and more.

Thanks to this uncomfortable but all-too-believable wave of media attention, everyone could easily see this had to stop. Full stop.

A patron saint, for fundraising?

Olive Cooke’s untimely death was not caused by bad fundraising. Yet the massive, sustained media coverage that followed did cast a spotlight on a substantial culture of unsavoury fundraising practices, and on a prevailing attitude of mind in many charities that was focused on increasing the money coming in yet cared little if at all for the hundreds of thousands of people sending it and how they might feel about the process of being over-aggressively solicited for ever increasing, ever more frequent gifts. That, we just have to change. So, it seems we might now agree, Olive Cooke deserves to be considered the patron saint of UK fundraising, because her death and the furore that followed it became the symbols and the catalysts that UK fundraising so desperately needed, to change their practices for good. The Olive Cooke affair, as it has become known, was about the diminishing of fundraising, the reducing of it to a remorseless series of persistent, pushy, even aggressive, asks. Through her untimely, unhappy death, Mrs Cooke has changed and is still changing that. We owe her our undying gratitude.

Linked articles

Any short excursion into Google will produce connections to a multitude of articles and images relating to the Olive Cooke saga and subsequent connected events. Here are just a few links to articles from this writer that were written at the time to chronicle aspects of this story as I was experiencing it.

- You have six minutes to defend or redefine fundraising... http://www.kenburnett.com/Blog59Sixminutes.html

- Where now for fundraising? http://www.kenburnett.com/Blog60Wherenextforfundraising.html

- Evolving into the inspiration business. http://www.kenburnett.com/Blog61theinspirationbusiness.html

- The future of fundraising. http://www.kenburnettom/Fundraisinghastochange.html

Other articles available online include:

The Sun:

- Killed by her kindness.

- Rotten chuggers.

- Hundreds of complaints over how charities behave after death of poppy seller.

The Guardian:

- Poppy-seller who killed herself got 3,000 requests for donations a year.

- Long-serving British poppy-seller died after being ‘tormented’ by cold-callers.

The Independent:

UK Fundraising: