Dr Barnardo’s Homes: how the death of Carrots led to a powerful slogan, from 1866

- Exhibited by

- SOFII

- Added

- August 25, 2011

- Medium of Communication

- Direct mail, publications.

- Target Audience

- Individuals.

- Type of Charity

- Children, youth and family.

- Country of Origin

- UK.

- Date of first appearance

- 1874.

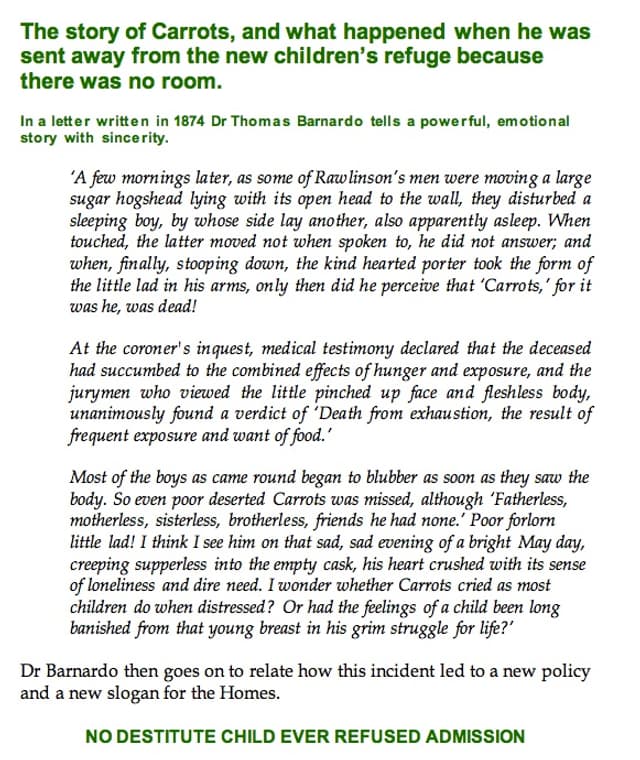

SOFII’s view

The story of the famous Victorian philanthropist Dr Thomas Barnardo’s meeting with the orphan Jim Jarvis in 1866, their tour of the rooftops of Whitechapel and his subsequent encounter with 11-year-old John Somers, known to all as ‘Carrots,’ come to us from Dr Barnardo’s autobiography, The Open Door, published in 1874. It was directly from these experiences and particularly the tragic death of Carrots that Dr Barnardo evolved the policy and slogan of the ever open door for his children’s refuge – a fundraising breakthrough if ever there was one.

Fine writing and sincerity are essential bedfellows in good fundraising communication. What I like about the extract from Dr Barnardo’s account, opposite, is its authenticity matched with simple emotion. His sincerity shines through. Sadly, most professional fundraising communication that we see these days doesn’t compare. Painful to admit, 135 years ago a gifted amateur such as Dr Barnardo was using all the techniques of the direct mail copywriter’s trade, but routinely beating us on sincerity and the power of words.

Creator / originator

Dr Thomas Barnardo.

Summary / objectives

Though I doubt if Dr Barnardo realised it at the time, this story as it developed had the effect of forming and clarifying a policy that would apply to all of the Dr Barnardo’s Homes for waifs and strays that were to quickly open across the country. It soon became their slogan and rallying call: the ever open door.

Background

‘One evening, the attendants at the Ragged School had met as usual, and at about half past nine o'clock, were separating to their homes. A little lad, whom we had noticed listening very attentively during the evening, was amongst the last to leave, and his steps were slow and unwilling.

'Come, my lad, had you better get home? It's very late. Mother will be coming for you.'

'Please sir, let me stop! Please let me stay. I won't do no harm.'

'Your mother will wonder what kept you so late.'

'I ain't got no mother.'

'Haven't got a mother, boy? Where do you live?'

'Don't live nowhere.'

'Well, but where did you sleep last night?'

'Down in Whitechapel, sir, along the Haymarket in one of them carts as is filled with hay; and I met a chap and he telled me to come here to school, as perhaps you'd let me lie near the fire all night.'

This was the first meeting with Jim Jarvis, a street urchin of about 10. Jim was typical of the hundreds of orphans who lived on the streets in nineteenth century London, one of many destitute children then who were either orphaned or abandoned and had no place to live. They were known as the ragged children and theirs was a rough life. During the day they wandered through the alleys of the East End of London begging from strangers. They were always in danger of exploitation by professional criminals. If begging did not work then stealing food from market stallholders was their only alternative. None went to school or had an adult to care for them. These were the forgotten boys and girls of nineteenth century England.

Barnardo tells how after their meeting Jim then took him down to the 'lays' around Petticoat Lane where children slept. Though familiar with the destitution of the families in London’s East End, Barnardo and his colleagues knew nothing of the hidden world of those children who had been orphaned or cast out by their own families. He was amazed and appalled as Jim led him around back streets, climbing over roofs to see children sleeping huddled amongst the chimneys for warmth and felt he had to do something to help them.

First he let Jim stay at his lodgings that first night. The next day he found him lodgings, which Barnardo paid for. The two companions went on other night searches and before long Barnardo had 15 children whom he had found homes for.

Night after night 10-year-old Jim Jarvis showed Barnardo the appalling life that street children led. He taught him how to find the hiding places where the very young children slept – in barrels, on rooftops, under market stalls, anywhere in fact where they could sleep safely, sheltered from the wind and rain.

Thomas Barnardo had some soul searching to do. He had wanted to train as a doctor and go out to China to be a missionary, but Jim had shown him a very real social problem in London’s East End. Should he stay in London and help rescue other destitute boys and girls?

He placed an article in The Revival saying he would host a tea meeting for children. The first of these took place in November 1867 and, amazingly, 2,347 children attended.

During a missionary conference he seized the opportunity to report the plight of these children. The audience was amazed by what Barnardo told them. One young servant girl gave him money to help his work, which touched him greatly for the girl must have taken a long time to save the money.

Barnardo’s story was reported in the press and when the seventh Lord Shaftesbury, a politician and philanthropist, read it he asked Thomas Barnardo to take him to see the children. So one night they went to Billingsgate and found as many as 73 children, mainly boys, sleeping out in the open. Lord Shaftesbury was appalled and could not believe what he saw. He said, ‘All London should know of this!’ He promised that, if Barnardo worked with these children, he would help.

Other influential people wrote to Barnardo asking him not to go to China but instead to organise relief work for London’s destitute children. Another politician, Samuel Smith, offered financial backing to Barnardo if he would do this. A banker called John Barclay also offered financial help.

John Somers, called Carrots, was just 11 years old when he died. He had lived alone and shunned on the streets for four years, from the age of seven. That he had turned the boy away in such a desperate condition and so close to death bore heavily on Thomas Barnardo for the rest of his life. He vowed that Carrot’s short life would be a beacon to him and to the homes he determined to set up.

I first heard the story of Carrots when I was about 10 years old, helping my mother who was a volunteer collector for Barnardo’s in our small town. It affected me deeply then and I have never forgotten it.

Other relevant information

In 1874 Thomas Barnardo opened an all night shelter at 10 Stepney Causeway called The Ever Open Door with the slogan ‘No Destitute Boy Ever Refused Admission’. In 1876 with the establishment of The Girls Village Home the slogan was amended to 'No Destitute Boy or Girl Ever Refused Admission’. This was then changed to:

NO DESTITUTE CHILD EVER REFUSED ADMISSION