Greenpeace International: the reinvention of face-to-face fundraising

- Exhibited by

- SOFII

- Added

- September 26, 2009

- Medium of Communication

- Face to face

- Target Audience

- Individuals, regular gift

- Type of Charity

- Environmental/animals

- Country of Origin

- Austria

- Date of first appearance

- 1994

SOFII’s view

This is perhaps one of the most amazing stories of modern fundraising, yet sadly it is known and understood by only a few. Its real star is the environmental campaigning nonprofit Greenpeace, which for at least the last two decades has consistently been one of the world’s most innovative and entrepreneurial fundraising organisations. It’s appropriate that Daryl Upsall and Jasna Sonne should tell the story, for they were instrumental in securing the fabulous outcome of the innovative fundraising method described here. How fabulous? Well in 2002, when Ken Burnett was researching the story for his updated edition of Relationship Fundraising, he found that in the preceding five years Greenpeace had, in just 18 countries, recruited more than 1.4 million new donors who each and every year were giving more than US$150 million. And that is just the tip of a very big iceberg. All from one basically quite straightforward fundraising idea. It’s a long story, but it’s worth it. Please read on.

To identify a new way of recruiting monthly direct debit (electronic funds transfer/autogiro) donors who were younger than the usual age of Greenpeace donors at the time (55).

Background

In 1993 Greenpeace’s fundraising worldwide was facing tough times – many major markets were slowing down considerably; in some, such as the USA, it was in serious decline. The internal perception was that the environment was going out of fashion with donors as new issues were emerging such as HIV/AIDS. Greenpeace’s donors had historically been recruited by cold direct mail and adverts in the media and in North America by door-to-door ‘canvassing’ for cheques. These tools were no longer performing as they had in the past. Unless something was done Greenpeace in many countries and at the International HQ was going to hit a major financial crisis.

Daryl Upsall, author of this exhibit, was hired in 1993 to turn the global fundraising of Greenpeace around before the situation worsened. Jasna Sonne, a highly experienced Greenpeace fundraiser based in Vienna, Austria, was one of the first members of what became the Greenpeace International (GPI) fundraising team. I remember when I told one of my referees for the post, the eminent fundraising guru George Smith, about what Greenpeace were looking to achieve he responded by saying, ‘If you get the job then I will carry your bags around the world for you’.

Little did George and Ken Burnett, both of the London-based communications agency Burnett Associates at the time, know that within a month of my appointment they would indeed be crossing the planet at my request to review the fundraising performance of various Greenpeace offices.

Ken and George’s reports from these trips to each country were instructive and invaluable in identifying the specific needs and changes to the fundraising that needed to be made in each country they visited, but of far greater value was the conclusion that could be drawn when the common problems and needs of the Greenpeace fundraising family were consolidated.

In short, we concluded that fundraising within Greenpeace at that time was largely undervalued nationally and internationally. The supporter base was in decline, ageing and largely based around special appeals and one-off gifts. The different techniques to recruit new donors were becoming less effective and Greenpeace’s fundraising in most countries was mostly for low-value donors (more of this elsewhere on SOFII). So we decided,

- There could be no more ‘business as usual’.

- We needed to up the quality of our fundraising staff through training and bringing in new talent.

The Smith and Burnett reviews had also clearly identified that recruiting donors onto direct debits would be the way forward, especially via schemes such as Frontline (developed by Burnett Associates for Greenpeace UK). It was clear that these schemes would provide an opportunity to build a long-term, growing and sustainable revenue stream for Greenpeace worldwide.

In 1993 only 18 per cent of Greenpeace donors worldwide were on monthly giving schemes.

For Greenpeace the ‘Holy Grail’ was to find a way to recruit new, younger donors onto a monthly giving scheme. Who would have believed that the solution was going to come from that fundraising capital, Vienna, Austria?

When Ken Burnett first visited Greenpeace Austria with the monthly giving message in 1994 Austria was a poor relation of the Greenpeace world, with very few regular donors. Yet across the border in Germany, Greenpeace could boast 350,000 people paying by direct debit. Direct debit then wasn’t even possible in Austria. But all this was to change, rapidly and dramatically.

Jasna Sonne takes up the story.

It was a hot day in June 1995. Just weeks before, President Chirac in France had decided to resume nuclear testing in Muroroa in the South Pacific and the oil multinational Shell was preparing to dump its giant but now old, contaminated and redundant Brent Spar platform into the North Sea.

In little Austria, in a beautiful garden restaurant in Vienna, a lunch meeting took place between the interim executive director, the fundraising director and some other fundraising staff of Greenpeace and two representatives of a small fundraising agency called Dialog Direct. Its purpose was to sign a contract with this new agency.

I was the acting executive director, filling the post on behalf of Greenpeace International. My colleagues, especially fundraising director Gerald Kaufmann, had prepared long and painstakingly for almost a year to get to this stage. I knew Gerald would do nothing without good reason. Only many months later, back at my position at Greenpeace International, did I fully realise the significance of what I was signing that day. It changed the course of Greenpeace’s fundraising and finances and that of many other charities around the world.

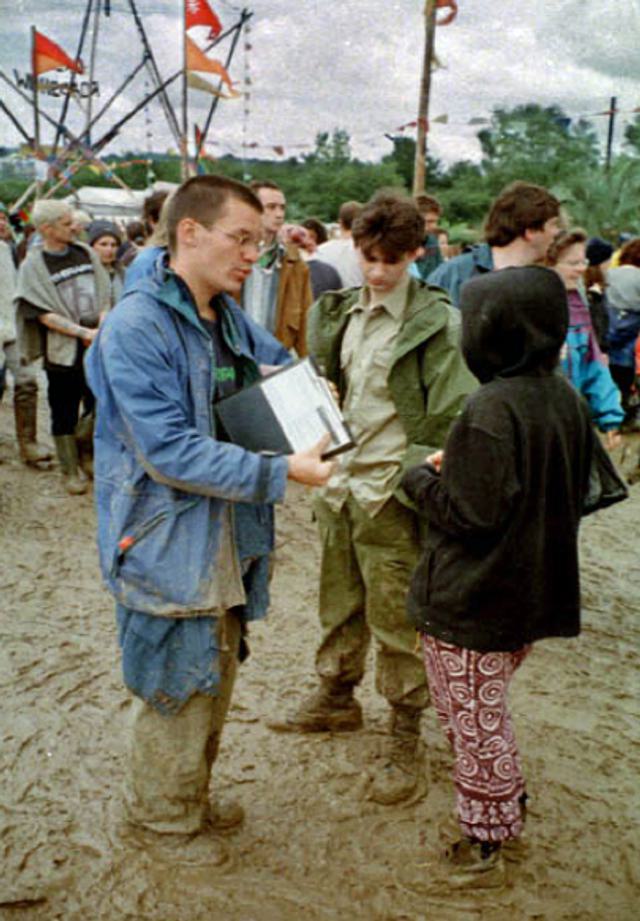

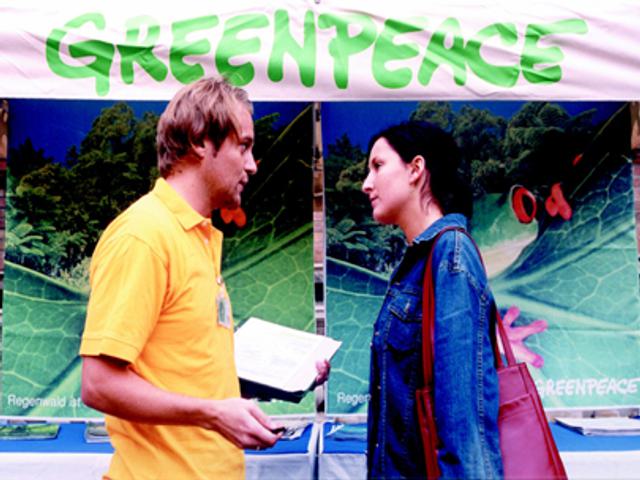

The agreement was to test a unique new fundraising activity to be carried out in public. The idea was to approach prospective donors in public places such as town squares, street corners, etc with the hope that approximately a thousand people would sign a special banking form, filled in by paid staff working on the street. It was actually a very long direct debit form and it committed these new donors to pay a donation to Greenpeace every month. Nothing like it had been tried before.

At that time in Austria people still mostly paid their bills by a banking slip that was posted or taken to the bank for payment over the counter. In those days only energy utilities and the emerging market of mobile phone companies could charge electronically and automatically via the bank.

To reach the magic number of a thousand sign-ups it was assumed that approximately 10,000 contacts on the street needed to be made. To me at that time it seemed a great fundraising vision – even if a little crazy.

As Ken Burnett always said, what you need in fundraising is a functioning electronic banking system that allows you to raise funds wherever you are. Over the next months I realised how impressive this visionary new fundraising tool was working, as donations poured into Greenpeace Austria’s bank account almost with no limits.

Greenpeace in Austria was pioneering on a number of levels and it transformed giving on the street. Firstly, it did away with cash handling, a benefit both for the donor and for the organisation. Gerald Kaufmann’s meticulous work on banking systems and negotiations with banks proved invaluable for Greenpeace. Secondly, approaching prospective donors on the street, in public, being ‘Greenpeace’ physically on the corner and in front of the local supermarket, gave great public visibility and profile to the organisation, every day. Street fundraisers were clearly branded with clothes bearing the Greenpeace logo. It helped also that the start of this relationship was a real one to one, with people actually face to face, not a relationship hidden behind a database and a piece of direct mail read in private. It was a total new concept of public outreach and fundraising, and people loved it.

It soon became clear that 70 per cent of donors recruited were in the age band of 20 to 35 (the same age as the street fundraisers) who were young, committed people with a good understanding of the electronic world and willing to change the world by starting a lasting financial relationship with Greenpeace.

The test was a great success and the agency continued to hire more and more staff. Most of these were young, cool-looking students. ‘Dating and mating’, an ancient theme in communications, became a side effect and sometimes a problem that needed controlling. On the other hand, this huge team of young people were out there fundraising for Greenpeace – what an asset, what a great image for raising the profile of environmental issues with the public, especially the younger members of society.

By the end of 1995 Greenpeace Austria found itself with 13,000 new, regular supporters who were recruited with almost no loss in their second year.

The following year, Greenpeace in many countries was failing to retain many of the huge number of new supporters that had joined the organisation on the ‘green wave’ of French nuclear testing and the Brent Spar issue. Yet, through Direct Dialog, Greenpeace Austria recruited another 50,000 new supporters onto direct debit. The ‘lifetime’ of these new supporters was anticipated to be at around seven to 10 years or more. Furthermore, face-to-face became so successful in Austria that the Austrian Church provoked a debate in Parliament as to why Greenpeace was ‘taking money away from church collections’.

Slowly other organisations became interested in using the method of street fundraising – named direct dialogue. It was time for Greenpeace International to take the success of this fundraising tool globally. In 1996 Greenpeace started to implement ‘DDC’ (direct dialogue campaigning) worldwide. Today the tool is the primary method for recruiting new support for the organisation and is working successfully in over 20 countries, including China, Thailand, India, Latin America, North America and across Europe. Over the years many, many millions of euros of long-term income have been raised and over a million new donors recruited by this one method.

And it all began in Austria on that sunny day in June 1995.

Influence/Impact

By 1998 Greenpeace International was rapidly rolling out face-to-face fundraising across the world, both in public places and door to door. In every case it meant either setting up the programme in-house or creating the suppliers from scratch, as no suitably experienced or qualified suppliers existed at the time. In many countries it involved serious negotiations with banks to enable a nonprofit to run direct debits, and with local authorities and the police on the legality of a public ‘non-cash’ fundraising activity. Greenpeace had to learn how to manage long-term relationships with donors who were not interested in our traditional direct mail approaches – but boy, did they like the Internet, email and SMS. But that is another story for SOFII – after all, Greenpeace was raising US$50,000 per month via the Internet in 1993. These were pioneering times.

Then, at one of the famous annual Greenpeace international fundraising training workshops known as ‘Skillshares’, invited guest David Coe of Amnesty International UK saw at first hand the amazing success that Greenpeace was having worldwide with face-to-face fundraising. He simply decided to copy it at Amnesty. The genie was out of the lamp.

Within the last 10 years face-to-face fundraising has become the primary new monthly donor recruitment tool for hundreds of nonprofit organisations in over 30 countries. Greenpeace and, nowadays, UNICEF are pioneering it in new markets and in the case of Greenpeace India, integrating it with SMS and tree planting.

In the UK close to 750,000 new donors have been recruited through face-to-face fundraising; in Spain that figure will soon be 160,000; worldwide we are talking in terms of millions.

Finally, more than 70 per cent of Greenpeace supporters now pay by monthly direct debit and because of this Greenpeace’s revenues are secure and growing. But the mission is never fully accomplished. As with all fundraising tools, face to face needs to constantly adapt and change with the times, the technologies, new cultures and new generations. That should keep all of us busy for another ten years at least.

Merits

Across the world the approach Greenpeace developed for direct dialogue changed the way fundraising organisations recruit new monthly direct debit donors. It has raised millions, perhaps billions of dollars in the process.

SOFII’s I Wish I’d Thought Of That 2012 – Liz Tait presents Greenpeace

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image