Pliny the Younger and the first appeal for matching funds, c. 100 AD.

- Exhibited by

- Ken Burnett.

- Added

- September 20, 2010

- Medium of Communication

- Target Audience

- Direct mail.

- Type of Charity

- Country of Origin

- Italy.

- Date of first appearance

- circa 100 AD.

SOFII’s view

This is an important part of fundraising history as well as a fundraising first. Pliny was a young lad when mount Vesuvius erupted in AD 79. His uncle, Pliny the Elder, sailed too close to the action and collapsed and died, ostensibly from toxic poisoning. Because of his extensive letter-writing to many of the leading figures of his day Pliny the younger left an invaluable archive of insights to his time, ensuring that he would become perhaps the best-known Roman of them all. He was also one of the most generous and philanthropic.

Summary / objectives

Pliny the Younger, 61 AD – 112 AD, was famous for his letters, many hundreds of which have survived and together provide an invaluable record of the period. He started writing for posterity at the age of 14. One of his best-known accounts is of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius on 24th August AD 79, which engulfed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum and led to the death of his uncle, Pliny the Elder who prompted by curiosity set off by boat to get as close to the action as he could.

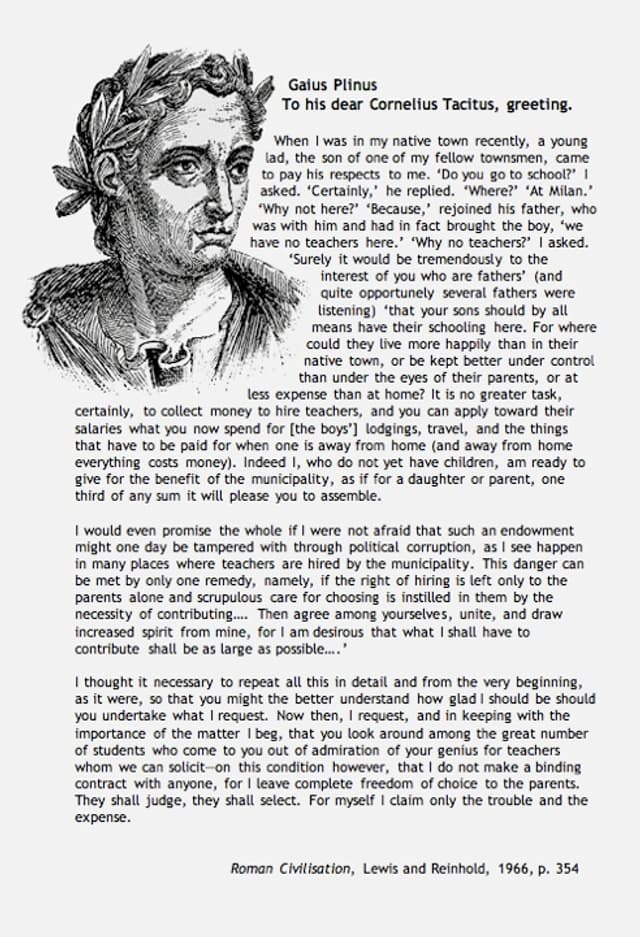

The full text of Pliny’s letter to create a matching fund is reproduced opposite. See also the related articles Two fundraising letters analysed and Mediterranean Philanthropy (both soon to be featured on SOFII – watch out for the updates).

‘I, am ready to give for the benefit of the municipality, one third of any sum it will please you to assemble. I would even promise the whole if I were not afraid that such an endowment might one day be tampered with through political corruption.

... Then agree among yourselves, unite, and draw increased spirit from mine, for I am desirous that what I shall have to contribute shall be as large as possible…’

See the full text of Pliny’s letter opposite.

Background

See http://www.unrv.com/culture/plinys-generosity.php

It is impossible to be sure whether Pliny the Younger was the most generous man in Italy because the detailed finances of his wealthy Roman contemporaries aren’t well documented. But thanks to his letters we can picture his life quite well, particularly his wealth. Statistical data about his finances support the view that Pliny’s generosity was outstanding.

Though Pliny the Younger was rich, his fortune was considerably smaller than that of other senators such as Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus, Quintus Vibius Crispus, L. Annaeus Seneca, Gaius Passienus Crispus, and many others whose net worth was in the hundreds of millions sestertii (possibly ranging from 200- 400 million). The reason for this massive gap of wealth between Pliny and the other senators was that Pliny's landholdings and properties were located mainly within Rome while more prosperous senators profited from having numerous estates in provinces beyond Italy. Pliny wasn’t poor, of course, but his fortune was relatively modest in comparison to some of his peers. Having come from a family with substantial existing wealth, Pliny was rich enough not to need any other career beyond being a senator. So he could concentrate on building his reputation and it was partly at least to accomplish this that he became perhaps the great civic benefactor.

Pliny would often donate money as political patronage to help his friends gain office and senatorial status. Significantly there were donations when a loan would have been more usual, though Pliny did expect some reciprocal benefits from his generosity. Once he donated 300,000 sestertii to a friend running for ‘election’ to the senate. Another example includes a similar donation of 300,000 sestertii to Romatius Firmus of Comum (Como) in order to obtain equestrian status so that he could have membership in the decuriae (the jury-panels of Rome). Pliny seems to have been particularly generous to the town of Como. His letters tell us that Metilius Crispus of Como also received financial help from him, in order to obtain a centurionate. The philosopher Artemidorus received an interest-free loan and Martial the poet had his travelling expenses paid for by Pliny.

The generosity described above may have been politically motivated but Pliny donated more often to the plebs urbana – the common people. Perhaps most notable of these donations was to build the fortifications of Como. To start, a rich man by name of Saturninus made Pliny his heir to a large fortune of 1,600,000 sestertii because of Pliny’s great reputation at Como. This reputation also stemmed from Pliny’s uncle, Pliny the Elder, who donated money for a temple in the city (a total of 1,450,000 sestertii was inherited by Pliny within the 15 years that his letters cover). Pliny, knowing Saturninus intentions, donated a third of the inheritance, about 400,000 sestertii, directly to Como, while he kept 700,000 sestertii for himself.

This was only a preliminary gesture however as there was much more to come for the people of Como. The largest example of generosity to Como was donated in three amounts. The library was the single greatest gift. From his letters we know that 500,000 sestertii was donated as alimentary funds followed by 100,000 sestertii for maintenance of the library. The largest donation was actually a sum of 1,000,000 sestertii to fund the construction of the structure. Not only did Pliny give the people a library, he provided public feasts, decorated their baths, monuments, and made many other gestures. His generosity to the town of Como alone totalled 2,466,666 sestertii.

Como wasn’t the only place to receive generous gifts from Pliny. The fortified town of Tiberinum was given a temple to house the imperial statues and Pliny even gave the town a large feast to celebrate its opening. Pliny restored another temple and gave another feast that was dedicated to the temple of Ceres. At Altinum, Pliny gave 800,000 sestertii for the restoration of two sets of baths and 200,000 sestertii for maintenance. He made a similar gesture at Hispellum.

As a final great example in terms of kindness he freed more than 100 personal slaves, though his agricultural slaves were excluded from this largesse because they were too valuable to his estates.

From his letters we know that Pliny’s total generosity within Italy came close to five million sestertii, but this is probably well short of a true total because his letters provide only a limited account of all the donations. His only known rival in Italy at the time was Matidia minor, sister in law of the Emperor Hadrian and great aunt of Marcus Aurelius, who was also particularly generous with her, largely inherited, wealth.

Pliny may well have been the most generous man in Rome, but his generosity probably pales in comparison to that recorded from patricians in other provinces. For example, Crinas gave 10 million sestertii to Massilia in his will; a donor at Aspendos in Pamphylia gave 8 million sestertii for an aqueduct; and Herodes Atticus paid 16 million sestertii for benefit of an aqueduct at Alexandreia Troas.

Many would assume that Pliny’s generosity was all directed towards finding glory and while there is some truth in that, careful review indicates a dedication to tradition and cultural improvement. He was following the encouragement of emperors to give public munificence, especially by Augustus. He did the very best that he could do with what he had as a true philanthropist, perhaps unlike those who were extensively rich and only donated to the public for political gain, fame or glory.

With thanks for background on this exhibit to Frank C. Dickerson and David Carrington. This exhibit is adapted from several articles available on the Internet, particularly at UNRV.com.

Other relevant information

Dr. Dickerson's research on the discourse of fund raising can be accessed at www.TheWrittenVoice.org

Here is another example of early Mediterranean fundraising

SOFII article: Philanthropy in ancient times: some early examples from the Mediterranean

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image