Fundraising ethics – raise more money while keeping your donors happy. What could be simpler? Part one.

Part one of an in-depth look into the ethics of fundraising with Ian MacQuillin.

- Written by

- Ian MacQuillin

- Added

- February 14, 2019

How can you tell what ‘the right thing’ in fundraising is?

How do you know what is and isn’t ethical in fundraising? Not only is it not an easy question but in fundraising we don’t possess nearly enough of the tools we need to be able to answer it. In this two part opinion piece Ian MacQuillin of the fundraising think tank Rogare gets to grips with this important but under-thought subject, starting with a look at theories of ethical fundraising.

Think of an example of an ethical dilemma in fundraising… Got one?

I bet a pound to a penny most readers came up with a corporate donor that conflicts with the charity’s mission, such as a tobacco company that wants to support a cancer charity. Many books, articles and conference presentations use just such an example.

Or if you didn’t think of the mission-conflicting corporate donation, were you thinking of a particular form of fundraising that you find distasteful – ‘chuggers’ perhaps, or maybe telephone fundraisers?

What these two examples have in common is that the answers are fairly black and white, but for different reasons.

A mission-conflicting corporate donation is prohibited by many codes of practice. It is therefore easy to say this is wrong.

And if you think ‘chuggers’ are unethical, that is equally black and white, to you, because that is something that you would never do. But just because you would never do something, does that therefore mean it would be unethical for anyone else to do it? It might seem black and white to you, but someone else might see it as white and black – or more likely, grey.

Between the certainties of what the rules say you can and can’t do and your personal belief system is where we encounter the myriad shades of grey of the ethical palette.

And fundraisers are just not well equipped to deal with these grey areas, in large part because we don’t have enough ethical theory that we can draw on to help us understand and resolve professional ethical dilemmas. This is why fundraising ethics is often presented in such black and white terms – by fundraisers either wanting to be told what is right and what is wrong, based on the codes; or someone who is not a fundraiser (it’s usually a non-fundraiser) telling them what is right and what is wrong, based on their personal moral conviction.

But there are many ethical dilemmas in the grey regions that neither the codes nor your personal conviction are well equipped to resolve. Here are just a few.

- Is it OK for a person to feel guilty if they decline to give in response to being asked? They might feel guilty simply because they are guilty, because they know they should be doing more. That’s not your fault, but it is because of you they now feel this negative emotion. Supposing you could raise more money by actually making people feel guilty, for example, for an emergency appeal, would you do it? (This is basically Comic Relief’s MO for the Red Nose Day telethon)

- Should you refrain from using images of beneficiaries that show the stark reality of their situation, if using that image impinges on the beneficiaries’ ‘dignity’? Who says it impinges on their dignity; how do they know? How are they even defining ‘dignity’? What if using the ‘dignified’ images raises so much less money than the more stark representations – as Oxfam found out a few years ago. Why should protecting beneficiaries’ dignity in marketing materials be more important than raising the money needed to lift them out of their undignified situation?

- Should you contact donors only if you have their consent to do so? More on this later.

- Would you engage in fundraising that aims to position your cause as preferential or more deserving than a different cause? This is what Pancreatic Cancer Action did in 2014 with their ‘I wish I had breast cancer’ adverts.

- Would you tell donors that you had absolutely no fundraising costs at all – because a different group of donors had already paid for them – and so ‘every penny’ they gave you would go ‘directly to the cause’? Would you be concerned this might be fostering among the general public a totally unrealistic expectation about the true costs of fundraising that could ultimately undermine trust in charities?

These are all big questions that the rules give little insight into. But it is equally hard deciding what the right thing is, simply based on what you ‘feel’ to be right: the more complex the issue, the harder it is to ‘feel’ your way through it.

And this is not to mention the plethora of day-to-day ethical dilemmas any fundraiser faces in professional practice, such as when to contact donors, how much to ask for, where to contact them, in which ways to contact them – all of which have ethical as well as best practice dimensions. Just because something is tried and trusted best practice doesn’t mean you ought to do it every time you could do it. And you have to know when you ought and ought not do it.

As a professional, it is incumbent upon any fundraiser to resolve these ethical challenges and arrive at a decision about the ‘right thing’ that is based on your professional knowledge, not just your personal opinion.

But how do you go about it?

This is where we start to do ethics. And if we are going to do it properly, we need to ground it in sound ethical theory that provides some concrete foundations to an ethical decision making process.

So over the two parts of this article, this is what we are going do. In Part 1, we’ll look at ethical theory generally – a kind of Ethics 101 primer – and what ethical theory there is that’s specific to fundraising. In part 2, we’ll look at how we can apply this in a couple of contexts. One will be the topic of donor consent. The other will be a discussion of this genuine, real life (a fundraiser actually faced this choice), ethical dilemma:

A woman with a terminally ill child says she doesn’t want to talk to a telephone fundraiser calling from a children’s hospital in the UK. Should she be called back at a later date?

What would you do if you were faced with the situation?

Mull this over as you read through the rest of Part 1 before we discuss how we could resolve this challenge is the second part of this article. But be warned. Not all the information you need is included in the statement above. That's deliberate because the aim of this exercise is not only to find out what people would do, but to shine a light on the processes they go through to arrive at that decision and the factors they consider in making the decision.

Ethical theory 101

I’ve often been criticised for being ‘too theoretical’ in my approach to fundraising ethics (and ironically, at the last conference I presented at, for not being sufficiently theoretical). But ethics is theory. Every time you try to resolve an ethical dilemma, you are doing theory.

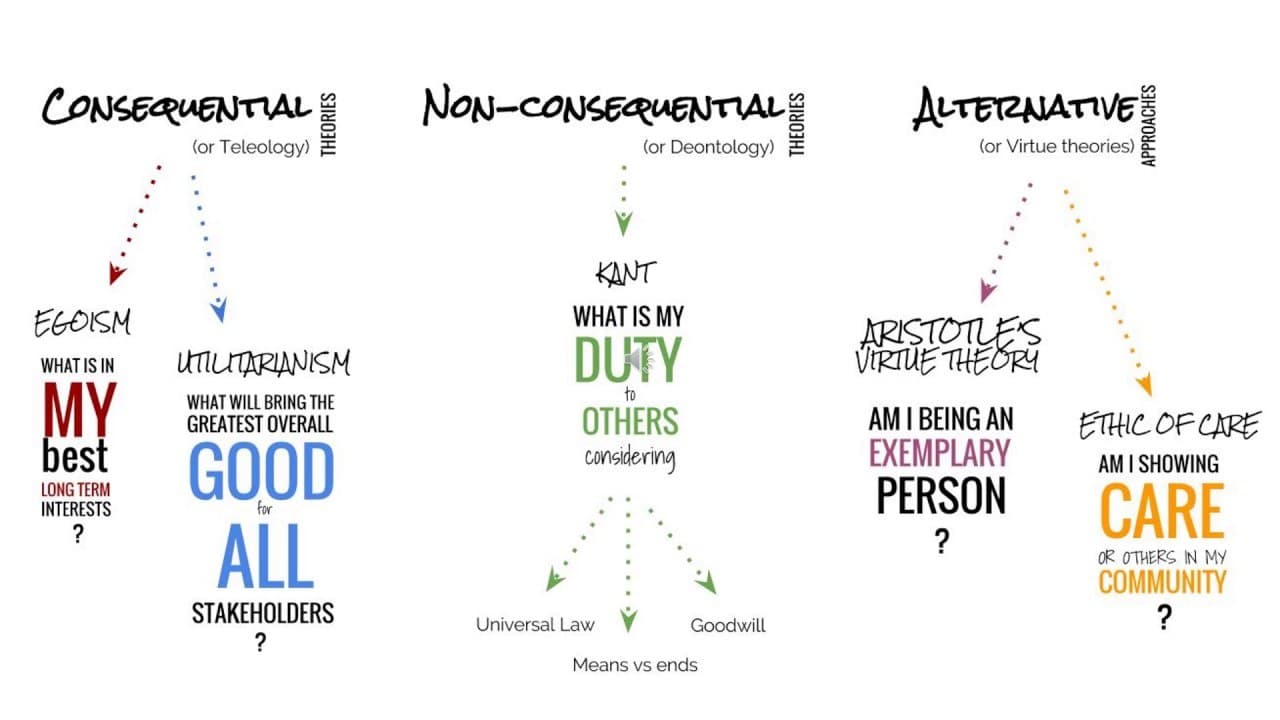

If you want to know whether to tell a lie and are wondering whether it’s OK because doing so will help some people, but are conflicted because lying just ‘feels wrong’, then you are grappling with ethical theory. In fact it’s one of the most fundamental divisions in ethical theory you can get – the division between consequentialist and deontological approaches to ethics (don’t worry, definitions in a moment).

So we can’t do ethics in any serious way without considering the theory behind it. Ethics without theory is opinion, guesswork, subjective value judgement and, quite possibly, ideology.

Here then, is a very quick primer on ethical theory. But if you’re already familiar with the ideas I’ve been developing (or you’ve got a philosophy degree) feel free to skip ahead.

First, it’s important to understand the difference between so-called ‘normative’ ethics and applied ethics.

Applied ethics helps you to work out what you ought or ought not do in particular situations; most codes of practice contain much of a profession’s applied ethics. By contrast, normative ethics – which is where we encounter theories about what is right and wrong and general ideas about how we ought to live – helps you to understand why you ought or ought not do those things.

At its core ethics is about doing the right thing for the right recipients, while normative ethical theories provide ways to answer the questions ‘what is the right thing?’ and ‘for whom are we doing the right thing?’. So this article is divided into one part about normative ethics (Part 1, this part) and Part 2 about how we can take these normative ideas and apply them in professional practice.

Two of the main branches of normative ethics are what are known as consequentialism and deontology.

Consequentialism, as the name suggests, tells you that the right thing to do is what has the best consequences or best outcomes, specifically actions that promote good and avoid harm.

Deontology is about doing the right thing because it is the right thing, because it conforms to a pre-existing moral principle, such as always telling the truth and never lying. Because it is not contingent on outcomes, deontology is sometimes called non-consequentialism.

Before we move on, it’s helpful to define what an ethical dilemma is.

You encounter an ethical dilemma when you have to make a choice between two right or permissible courses of action that both have potentially good and bad consequences. But it is not a choice between right and wrong, which is better described as a moral temptation. Deciding whether to steal an expensive drug you can’t afford because without it your child will die is an ethical dilemma. Deciding whether to mug someone because you want the contents of their wallet to buy a new pair of trainers is not.

It is also worth bearing in mind what ethics is not. It’s not science. It doesn’t give you incontrovertible right and wrong answers, which is perhaps what some people in fundraising expect from it. You don’t feed information into an ethical dilemma engine, crank the handles and expect the ticker tape output to tell you what to do.

Ethics is a theory-based decision-making process to make a choice in an ethical dilemma, a process that then allows you to better or less well justify that choice, depending on how well you went through the process. You might think you made the right choice and can justify it; someone else might have a better ethical critique of your actions (i.e. they think you are wrong). That doesn’t necessarily mean either of you actually is right or wrong.

Armed with this brief run though of ethical theory, we can move on to fundraising ethics, though again, if you’re familiar with my ideas, feel free to skip ahead to Part 2.

Ethical theory in fundraising

Most – in fact almost all – fundraising ethics is applied ethics and it’s to be found in various codes of practice.

Codes of practice tell you what you can and can’t do and so they create ethical prescriptions for professional practice. Doing something forbidden by your code is, by definition, unethical. But not all ethical dilemmas will be covered by the code. There will be lots of grey areas the code can’t help you with – such as whether it is acceptable that someone feel guilty if they decline a solicitation request – and when you encounter those, you need some kind of normative theory to help you to decide what to do.

Unfortunately, we have very little of that in fundraising. I’ve got a book on marketing ethics that has 90 chapters (it’s a PDF version), and that’s just the reprints of academic journal articles the book’s editor consider the best. If you collected every article on fundraising ethics published in a book or academic article, you’d be lucky to get half that number.

Many authors try to – rather haphazardly, it must be said – wrap a superficial deontological or consequentialist explanation around ethical dilemmas in fundraising. But what we need to resolve these ethical dilemmas and illuminate grey areas is a bespoke normative theory of fundraising ethics.

From what has been written about fundraising ethics, we can pull out three candidates for a normative theory of fundraising ethics: trustism, donor centrism, and service of philanthropy.

Trustism

This says the right thing to do in fundraising is the one that maintains public trust. So fundraising is ethical when it does this and unethical when it does not. The question you must ask in trying to resolve an ethical dilemma is whether your proposed resolution would maintain or undermine public trust. But this is a consequentialist idea, so it needs evidence about what the effects on public trust actually are (or likely to be). You can’t just assume or believe that trust would be damaged.

Donor centrism

Most fundraisers will be familiar with this idea as a form of best practice. From an ethical perspective, this says that the right thing to do in fundraising is basically do what your donors want – to put their needs, wants and desires at the heart of everything you do as a fundraiser. But this comes in two variants.

The consequentialist version of donor centrism requires you put the donor at the heart of your activities because this is the best way to raise more sustainable income: the better an experience you give them, the more they will give. This is how Ken Burnett describes relationship fundraising in his eponymous book.

But the deontological variant requires you to put the donors’ wants and desires at the heart of what you do because this is morally the right thing to do for the donor. And strictly speaking, this is the case even if doing so doesn’t result in raising more money.

It’s an important distinction, as we shall see when we look at the ethics of donor consent in Part 2.

Service of philanthropy

US fundraising guru Hank Rosso said fundraising is the servant of philanthropy and so the ethical role of fundraising is to bring ‘meaning’ to a donor’s giving. Fundraising is thus ethical when it brings this meaning, and unethical when it does not. This idea – which casts fundraisers in the roles of philanthropy advisors – has a bit more transaction in the USA than the UK.

Each of these positions has strengths and weaknesses and for more information on each I’d refer you to Rogare’s white paper on fundraising ethics, which you can download here.

I would suggest that most codes of practice are predicated on trustist and donor centrist fundraising ethics. Both these, and service of philanthropy, confer most of a fundraiser’s ethical duties on donors (or even non-donors). It’s actually quite staggering – and a little bit shocking – that in almost everything written about fundraising ethics, beneficiaries are rarely mentioned, to the point you could easily conclude that fundraisers owe no ethical duty to their beneficiaries at all.

So to correct this and bring the beneficiary back into ethical decision making, I developed a normative theory of fundraising ethics I call rights-balancing fundraising ethics.

This states that:

Fundraising is ethical when it balances the duty of fundraisers to ask for money on behalf of their beneficiaries, with the relevant rights of donors, such that a mutually-optimal outcome is achieved and neither stakeholder is significantly harmed.

One of a donor’s key rights will be the right not to be subjected to ‘undue pressure’ to donate. This is the phrase used in the Fundraising Regulator’s code of practice in the UK and mirrors the term used in the Charities Act 2006. But what counts as ‘undue’ pressure isn’t defined anywhere, while the use of the word ‘undue’ implies that some kind of pressure is ‘due’, or permissible.

So in everyday, professional practice, perhaps the main way this ethical balancing act will be used will be when fundraisers aim to balance their duty to ask for money with the right of donors not to be subjected to undue pressure to give.

But fundraisers won’t want to go back to first principles every time they encounter an ethical dilemma in fundraising. It’s time-consuming and intellectually intensive trying to weigh all the factors to achieve a balance and the answer probably suggests itself without going through this whole rigmarole. People use rules of thumb all the time to help them make decisions and navigate professional and social life. We can do that in fundraising ethics too.

In any practical ethical dilemma in fundraising, the rule of thumb will probably be to do what you think the donor will want. That’ll probably prevent harm to the donor (such as feelings of guilt and other negative emotions), protect sustainable income, and maintain public trust, while any potential harm to beneficiaries from foregoing a possible donation is likely to be minimal to non-existent. The challenge of course, is whether you can say with confidence what your donor really wants – based on your professional judgement and experience, which hopefully includes hard evidence – or are you just guessing or being swayed by your own personal views.

But rules of thumb can only take us so far. There will be times when we’ll need a much more tailored and sophisticated solution to the challenge before us and this will be especially true when we move the ethical dilemma out the domain of day-to-day professional practice and into sector-wide policy-making, where bad decisions have the potential to seriously harm beneficiaries.

I’ll illustrate this when I take a look at the ethics of consent when we start Part 2 of this article, which we can now move on to having armed ourselves with a brief overview of the ethical theory we need to know to better work through the applied dilemmas we’ll encounter in fundraising practice.

Editor's note: the question of ethics in fundraising is a fascinating and, as Ian shows, complex one. In part two next week Ian will explore how to apply ethical theory in practice.