‘Don’t we, as a sector, have a responsibility to hold ourselves to a higher ethical standard?’ Change for Good reviewed.

As the Great Fundraiser’s Bookshelf expands we bring you a review of Change For Good: Using Behavioural Economics for a Better World, by Bernard Ross and Omar Mahmoud. Ruby Bayley-Pratt of Amnesty UK examines the book’s message on behavioural economics in fundraising.

- Written by

- Ruby Bayley-Pratt

- Added

- August 30, 2018

Book review

Change For Good: Using Behavioural Economics for a Better World by Bernard Ross and Omar Mahmoud (SemioSCreation and The Management Centre 2018, UK, ISBN: 0692064362).

Reviewed for SOFII by Ruby Bayley-Pratt.

Warning: this book will make you question every decision you have ever made. But don’t panic, on the other side of existential crisis there is hope.

Building on the work of gurus and Nobel Prize winners Daniel Kahneman and Richard Thaler, leading global experts in psychology, marketing and fundraising – and minor celebrities – Omar Mahmoud and Bernard Ross take the reader on a journey through frankly unsettling behavioural economics theory and apply it to the pursuit of positive social change in a remarkably accessible way.

Behavioural economics studies the effects of psychological, cognitive, emotional, cultural and social factors on the economic decisions we make and explores how these vary from classical economic theory. Essentially, it challenges our very fundamental beliefs about the thought processes and thus, the rationality, behind our decisions.

I finally relented and laboured my way through what is considered the behavioural economics ‘bible’ that is Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow (Penguin Books) last year after hearing about it everywhere – notably in an episode of Krista Tippett’s On Being podcast, which explores why and how we contradict ourselves and confuse each other (I would highly recommend a listen [1].

With my limited exposure to the world of economic research, I found the book tough going, but one thing became clear: if I, as a fundraiser, and if our sector – across all disciplines – could successfully understand and then apply these concepts to our work it could be revolutionary.

Whilst traditional texts on behavioural economics tend to focus on the ‘why’, Change For Good gives precedence to the ‘how’. Rather than spend chapters extrapolating the nuances of the – albeit extraordinary – theory, this book focuses on what we can actually do in response. It is packed with examples of real-life scenarios that demonstrate how we can adapt our fundraising asks or our campaigns to change the theory into action and effect greater change. Particularly Informative are the anecdotes about the authors’ more relatable replications of Kahneman et al’s original research experiments at events like the IFC [2].

The marriage of this practicality and the accessible language and visuals in Change for Good (plus a noticeable absence of Ross’ characteristic references to the likes of Voltaire) make behavioural economics comprehensible and, most importantly, applicable.

From anchoring donors with a large, unrealistic figure (see US Girl Scout who raised $80,000 over 12 years by first appealing for a donation of $30k and, upon rejection, asking people to buy cookies and pay what they could [3]) and not leaving potential supporters dangling at 66 per cent of your crowdfunding target (hint: donations will stagnate [4]), to the frustratingly counterintuitive conclusion that presenting potential supporters with data and statistics - and thus stimulating rational thought - actually encourages them to give less cash [5]; this book is packed with manageable, practical, and well-evidenced ‘hacks’ which have the potential to change behaviour and revolutionise your fundraising practice.

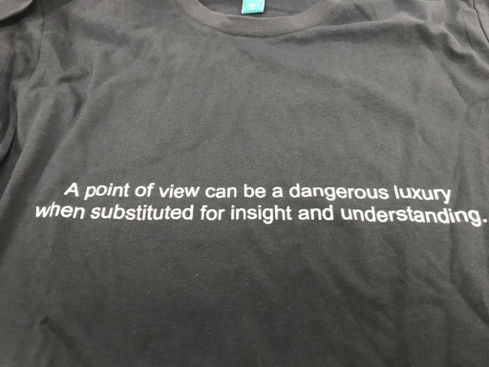

There is clearly ample evidence of the effectiveness of behavioural science when it comes to driving social change, but is it ethical? Where is the line between harnessing this insight - into factors that many of us are not even aware affect our decision-making - and manipulation? We know that these techniques are widely used by the commercial sector and often to the detriment of the consumer. Kudos to the authors for not skirting around this issue. The book highlights examples like clustering information on web pages in a way that prompts people to take financial deals that aren’t actually in their interest and fast-food chains offering ‘meal deals’ to encourage people to eat larger portions of unhealthy food. These brands are so often in direct contradiction with what we’re trying to achieve. Do we want to align our tactics with theirs? Don’t we, as a sector, have a responsibility to hold ourselves to a higher ethical standard?

I firmly believe that the answer to that last question is yes. However, as this book, and Thaler’s research before it, rightfully point out, we must acknowledge and defend the fact we are operating in a very different context from these commercial entities; one in which we are ultimately working for societal good. Clearly, there is a question here about who is making the judgement about what counts as societal good. However, by stressing the importance of a robust ethical framework and transparency, Change For Good makes a compelling argument for the use of these techniques by those of us working within a social change agenda. One particular sentence encapsulates the rationale for me: ‘the results [of the technique] must benefit the nudgee not the nudger’ (i.e. the person making the decision rather than the organisation).

All that said, whilst the theory and its application outlined in Change For Good clearly have the potential to transform social change practice, after some reflection, I find myself questioning whether our sector is ready to build-in the infrastructure, processes, and, fundamentally, make the culture and mindset shift needed to implement this change. Sometimes it can feel like we are stuck in a perpetual loop of fire-fighting, trying to get things out - and in fundraising specifically, bring in the cash - with minimal resources and as quickly as possible. Our responsibility to the donor, beneficiary, or our ‘ethics’, leaves us risk-averse when it comes to testing new things, failing, and learning. Our default, as much as we might shy away from the accusation, is to fall back on ‘the way things have always been done’. As individuals, organisations, and a sector, we need to take the time to reflect on this challenge.

But whose job is it to bring about the change? I’m afraid I don’t have an answer. But as agents for social change, we must use this book and live its lessons. I would recommend you read it cover to cover and then have it take pride of place as an appendage to the pictures of your family/cat on your desk. This book is a tool. Refer to the checklist at the end at the inception of every campaign, project, bit of comms until you have internalised its principles. Scan that page, blow it up, and stick it everywhere (don’t tell ©). It is going to take energy, leadership (and not just on the part of Leadership) to really make the most of what this book has to offer. But if we can do it, there is no doubt in my mind we can accelerate our journey to making the world a better place.

To discover more great fundraising books, reviewed on SOFII, click here.

[1]https://onbeing.org/programs/d...

[2] http://resource-alliance.org/e...

[3] (p.66)

[4] (p. 102)

[5] (p. 160-161)