Do you have the answer to the donor consent issue? Here’s a behavioural scientist’s perspective

- Written by

- Kiki Koutmeridou

- Added

- September 14, 2017

“So, you have the answer to the consent issue?”

“Yes, the answer is there is no simple answer. New data proves ‘the answer’ changes charity by charity”

Overview

If you don't measure failure you can call anything a success. But it’s beyond doubt our sector has failed to find the most effective way to gain supporter consent (if we define ‘failure’ as spending a lot of money to lose a lot more).

Enormous charities, with near infinite budgets for testing and innovation, have very publicly made the move to full opt-in. But new data proves that the 'your tick saves lives' approach they took performs worse than any other.

The trouble is that you only find that out if you test the right things in the right way. Only a handful of charities have. Here's an example of one that got it exactly right.

Context

As a behavioural scientist, the challenge of getting an empirical and applied answer to how best to gain supporter consent fascinates me. As a fundraiser, the lack of robust testing shocks me. I’ve seen a lot of dangerously unscientific ‘research’ translated into fancy looking presentations. But I’ve seen nothing that comes even remotely close to being a solution.

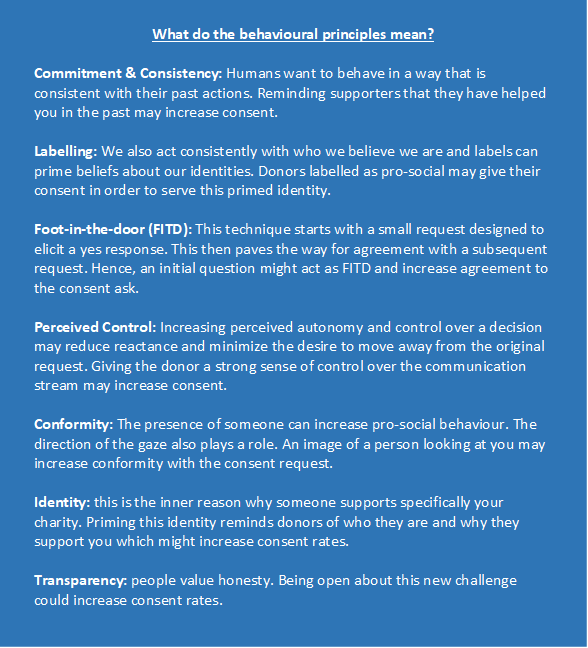

So, last year I partnered with the Behavioural Economics Research Group at City University London to study the behavioural science principles affecting supporter consent. We tested 46,000 executions of principles. You can access the full results here.

These initial findings provided insightful guidance on generic winning principles. But, as we stressed at the time, there was always going to be an enormous difference between generic factors and organization specific ones.

And now we have overwhelming proof to back this up.

One example I can share is the work we’ve done with Crisis, a UK charity that supports homeless people. Testing was done with existing supporters both on winning behavioural science principles from our prior research, and new principles uniquely related to Crisis’s needs.

Most importantly, these principles were translated from theoretical into copy and design reflecting Crisis’s mission, tone of voice and brand.

It’s important to stress Crisis weren’t just testing the right things - they were testing in the right way.

Testing only one copy and design version of each principle is risky. The near infinite choice of execution you’re faced with means there may be other more effective ways that never get tested. Again, if you don’t measure failure anything can be called success. But it won’t be successful.

For this reason, we used the DonorVoice Pre-Test tool - a sophisticated, multivariate (observing statistical outcome variations) online testing platform. This allowed Crisis to not only run many thousands of A/B tests simultaneously, but to do so faster than they could have done with only a handful. This allowed us to compare not just multiple principles but also multiple copy and design executions of each principle.

This testing told us two crucial things:

- The relative importance of each theoretical principle, or concept for Crisis

- The most effective way to execute this principle/concept into words or images, once again for Crisis.

What we tested

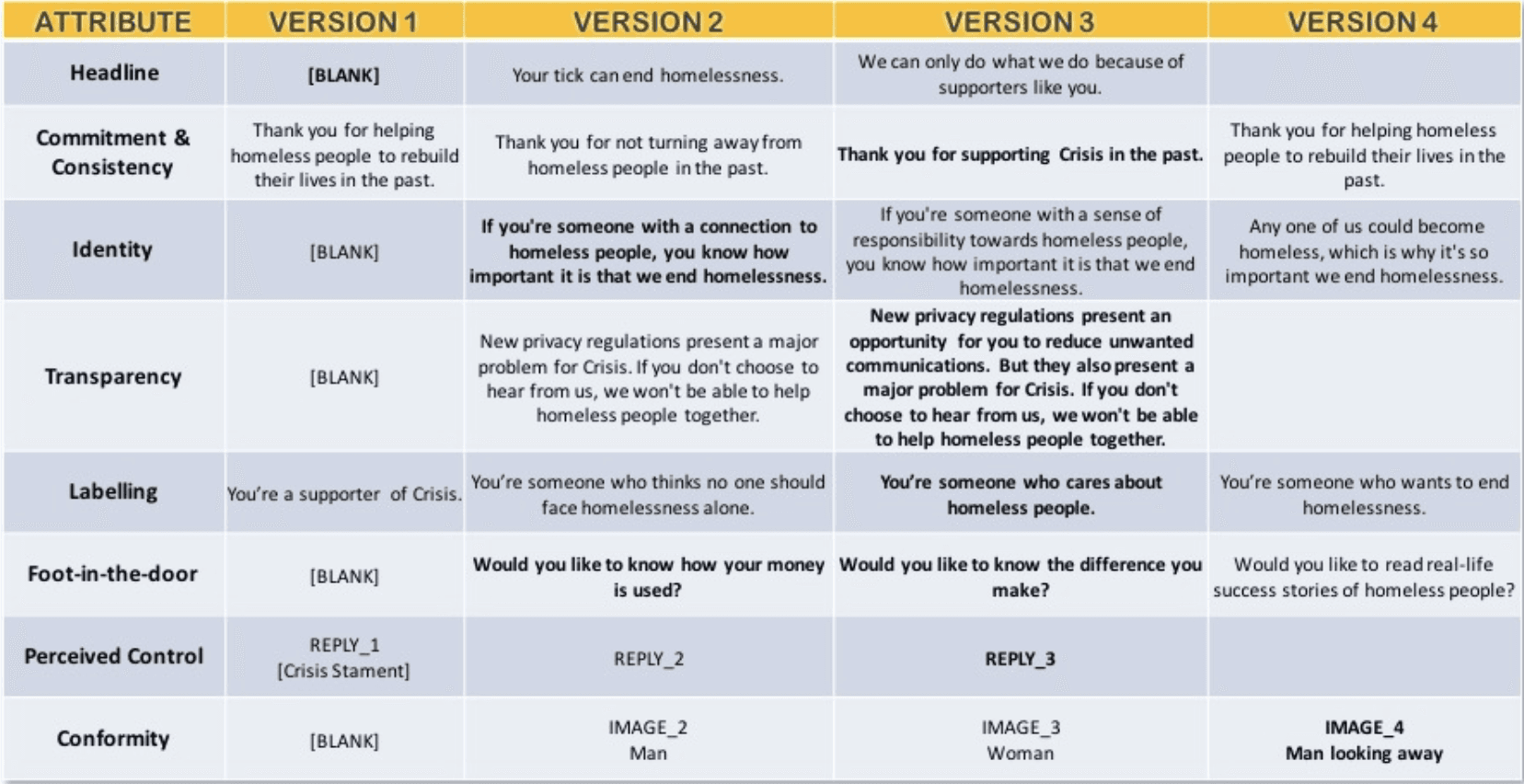

Crisis wanted to test two different concept ideas. The first was their version of the supposedly ‘best practise’, your tick saves lives, tag line. So, we included the message your tick can end homelessness. The second concept was about the donor’s impact and the role they play. This was reflected in the message we can only do what we do because of supporters like you. All the behavioural science principles shortlisted in the table below were tested.

So, what worked?

Let me start with a cautionary note. These findings are unique to Crisis and whatever follows isn’t a recommendation for application. Rather, it’s intended to show how the power of the behavioural principles differ significantly when we go from generic to charity-specific copy.

What we found

So, what worked?

Let me start with a cautionary note. These findings are unique to Crisis and whatever follows isn’t a recommendation for application. Rather, it’s intended to show how the power of the behavioural principles differ significantly when we go from generic to charity-specific copy.

What we found

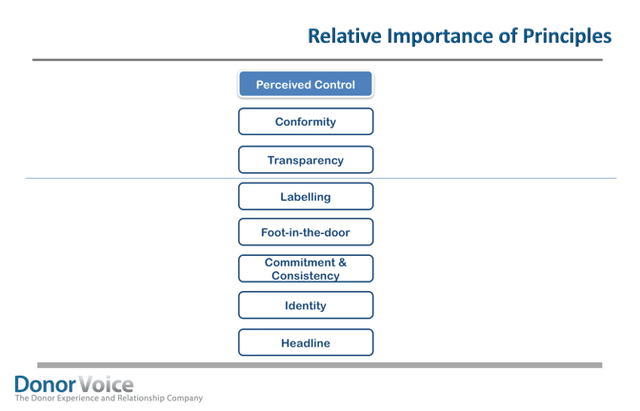

DonorVoice’s pre-test tool reveals the relative importance of the attributes. For Crisis, the principles with most impact were perceived control, conformity and transparency.

So far, these results validate our previous findings. Perceived control and conformity were the two most important principles in our previous study too. Thus, we can begin to assume that giving donors control and an image of a person could influence consent. However, the most effective way to execute these two principles might still differ from charity to charity.

But the above was the only parallel with our previous study.

The order of importance of all other principles (shown on the right) was unique to Crisis and didn’t reflect what we had found when we used a generic charity.

It is also important to note that the 'headline' was the least effective of all – as a reminder, this wasn’t a behavioural science principle but the concept ideas that Crisis wanted to explore.

The second piece of insight our Pre-Test tool provides is which of the copy versions within each attribute/principle is the most impactful. The table below shows a summary of everything we tested. Each row is a principle and the different columns represent the different versions for each principle. The winning version of each principle is shown in bold.

Most of the findings are self-explanatory but there are a few things I should bring to your attention:

1. Looking at the first row, the Headline, it becomes clear why it was last in the ranking order; having no headline was actually better than having either the ‘your tick’ or the ‘donor impact’ concept. I repeat. No message was better than either of these two messages.

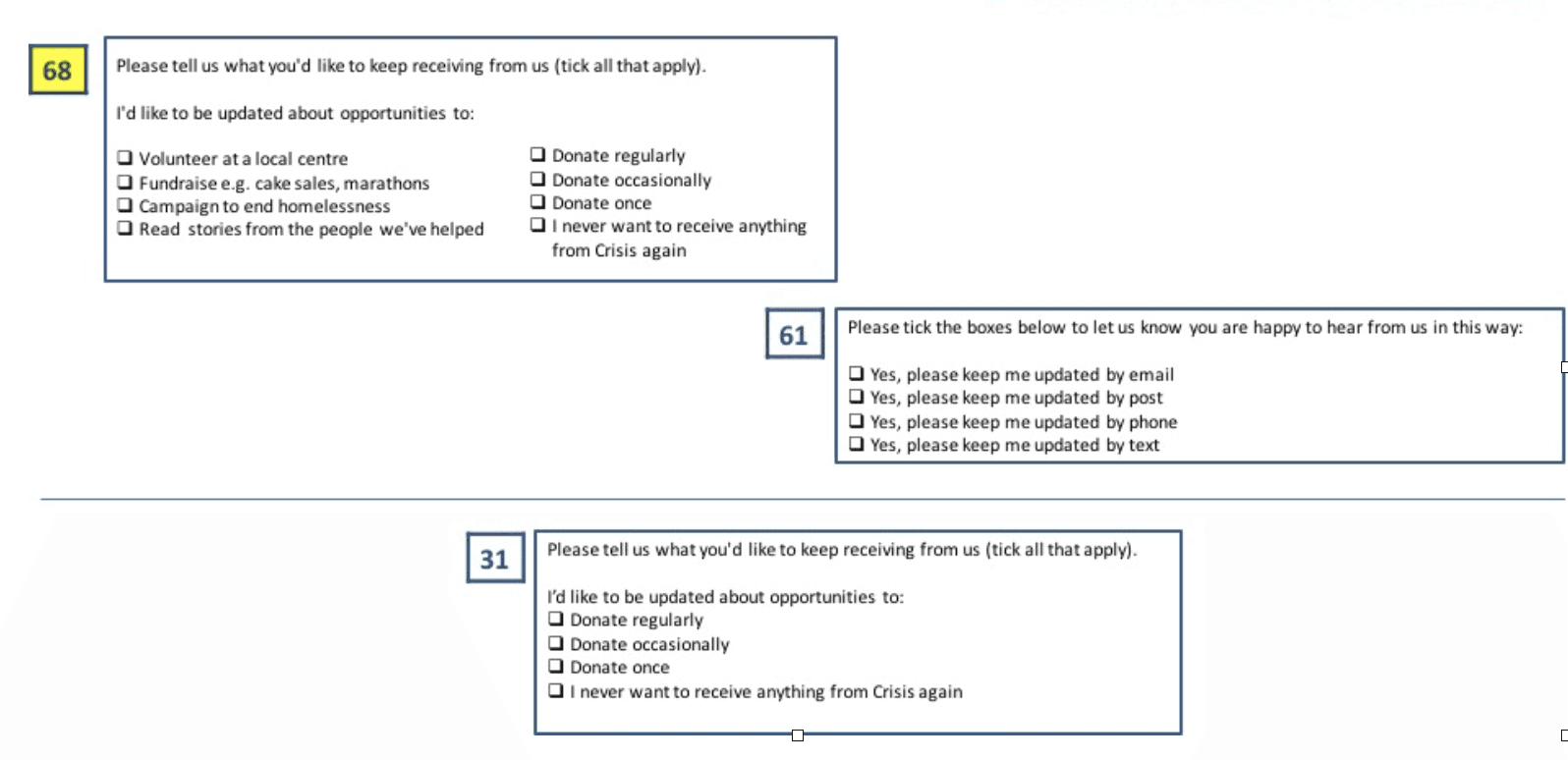

2. The above table doesn’t show exactly what we tested for the Perceived Control principle. In our prior study, we offered control over the frequency of all communications (weekly, monthly, yearly) and channel control. Channel control had performed better than the controversial –and scary – control over frequency. Good news!

But the question remained. Could we offer a type of control which would outperform the standard channel preference?

In the image below, you can see the three types of control we tested this time: Crisis’s consent statement offering the standard channel control, a statement offering control over donation frequency, and a third statement offering control over content as well as donation frequency. Next to each type of control, you can also see some scores. These are preference scores. The higher the score, the higher the preference. In addition, they show magnitude of the effect; a score of 60 is twice as preferred as a score of 30.

Although offering donation frequency control is the least preferred option, combining it with control over content outperforms channel control. This means that charities may be able to differentiate themselves by offering control over their unique content. This finding warrants further exploration to find which content options are the most effective for each charity. It’s also worth exploring what the best way to combine these different types of control is.

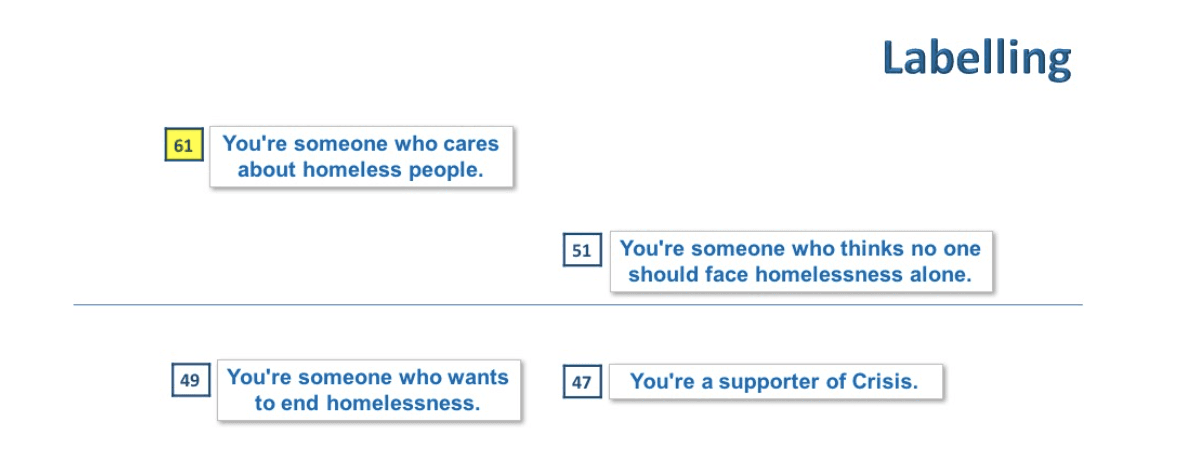

3. Finally, we need to stress the importance of testing behavioural science principles that are customised to your charity. What works for Crisis might not be the most effective for your charity. For example, our previous research using a fictional charity, found that the label ‘supporter of this cause’ was the winning one. But, as shown in the image below, the label ‘you’re someone who cares about homeless people’ was the clear winner for Crisis. Actually, the label ‘you’re a supporter of Crisis’, which in our study scored the highest, here was the lowest scoring label.

Using generic language, or applying insight that was generated for someone else, could lead to sub-optimal performance. If Crisis had applied only generic insight, instead of testing their own customised copy, they would have risked losing contact with many thousands of people who’d otherwise have happily continued their support.

The only way you can be sure not to make that mistake is by testing the right things in the right way.

For more information about this case study and the methodology, you can arrange a free consultation with Dr. Koutmeridou by emailing chulme@thedonorvoice.com