Confessions of an unethical nine-year-old fundraiser

- Written by

- Norma Cameron

- Added

- November 27, 2013

One of the golden rules of major gift fundraising is that before you ask others for donations you should donate yourself. Perhaps we should delve deeper and discover our true philanthropic selves. If the memory and experience of a single gift can provide a greater level of comfort and confidence in asking others to donate, then just imagine what might happen after discovering the whole story.

As part of my approach in teaching fundraising, I always recommend such exploration. So I thought I’d share the story of my first step into philanthropy.

Cemeteries, snowdrops and a philanthropic epiphany

My first memory of anything to do with collecting money for charity is the coin boxes that flanked the doors of Woolworth’s in my hometown of Wishaw in Scotland.

On one side was a black Labrador-shaped coin box representing Guide Dogs for the Blind. He (when I was young I thought all dogs were boys) always got a pat on the head and, sometimes, I’d drop a penny or two into the slot between his ears.

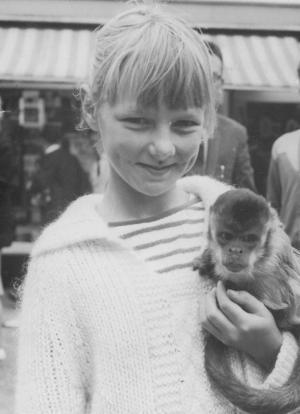

But my favourite was the coin box on the opposite side. She was a sad, yet beautiful blonde girl with a brace on one leg. My mum told me she was just like the children who lived in the Dr Barnardo’s orphanages.

She was clasping a teddy bear in one hand and a collection box in the other. She was about the same height as me and the paint around her nose was chipped. I liked to think it was worn down over the years by frequent kisses from a caring community.

On Saturdays my best friend, Esther, and I would head out to play. A favourite destination was the Belhaven estate. It was built in the sixteenth century and demolished in 1958 so there wasn’t much left. But the most magical place in our world was at the back of the grounds, hidden near the riverbank. It was a pet cemetery. Years later, I found out it was started by the eleventh Lord Belhaven around 1850.

This was where all the pets from the estate were buried. There were also elaborate headstones dotted around the grounds featuring carvings of horses’ heads – Lord Belhaven insisted in burying horses where they fell.

To put the allure of this pet cemetery into perspective, Esther and I regularly spent hours combing through human cemeteries too, recording inscriptions on headstones in secret notebooks. We competed to find the oldest grave, the shortest life and the best epitaph.

Every spring the pet cemetery was covered by what could be mistaken for a blanket of snow: thousands upon thousands of snowdrops. One spring I had an idea. It was a way to share these hidden snowdrops with others while raising money. So we returned later that morning with baskets and elastic bands.

We gathered snowdrops, tied them into large and small bunches, then trotted up and down our neighbourhood streets selling the large posies for six pence and the smaller for three pence. We told the surprised residents that we were collecting money for Dr Barnardo’s Homes.

After a few hours, our baskets were empty and our pockets were full. Jingling and jangling, we headed to my house to count our takings. We had raised 13 shillings and sixpence – a fortune, given that it represented nine weeks of pocket money. There it was, spread all over the kitchen table when my mum walked in and immediately asked where it had come from.

When we told her, she said, ‘What a lovely thing to do for all those wee children.’

But when I responded her smile soon faded. ‘Well, we said we were collecting for Dr Barnardo’s, but we didn’t mean it. We just want the money for ourselves.’

Now, my mother wasn’t an overly religious woman, but she was known to bring God into a conversation whenever it seemed useful. And, like a lot of Scots, she was quite superstitious.

‘You’ll know that God will have seen and heard everything that happened today. He’s watched all that money, especially the silver that crossed your palm. Now I don’t know what he’d say about it, but I wouldn’t be surprised if all that money left its mark because of the lies. But, it’s your decision. If you keep it and buy things with it then you’ll be one taking your chances with all that bad luck.’ And with that, she left us to ponder the situation.

The stirrings of conscience

We looked at all that money, weighed our options and decided to split the takings. Then moved quickly to talking about what we were going to buy with it.

The next morning, after a rather uncomfortable night scratching an increasingly itchy palm – the family headed to church. By the time I got home, my palm was redder than ever and I was wondering whether what appeared to be a black spot emerging in the centre might develop into a hole, as my older sister had predicted.

Later that afternoon, Esther and I decided that we would hand over the money to the local Dr Barnardo’s Home. On the following Saturday, together with our mothers, we were at the doors of an oppressive stone building.

I thought it a strange, almost eerie place. I wasn’t completely surprised at this reaction because ‘being dropped off at Dr Barnardo’s’ was a threat most parents used to curb misbehaviour. As we got closer to the large front doors, I felt myself grow ever smaller. I also noticed there weren’t any children to be seen on the grounds, or at any of the large, dark windows.

An older woman dressed in a tweed skirt and grey twinset greeted us. She stepped outside the door, closed it behind her and patiently listened to what we had to say. When we finished, she smiled, especially at Esther and me, and said thank you when we handed her the money. She asked us to wait for a moment and slipped back into the building.

She re-appeared with another woman and they invited Esther and me to return in a week’s time to have tea with the children as a way of showing their gratitude. Then, after shaking hands and more smiles, we left.

A few days later, a story appeared in the local newspaper heralding the generosity of two local children and their admirable efforts to help Dr Barnardo’s. It was even read out by our teacher in class.

The next Saturday Esther and I went through the large front doors of Dr Barnardo’s Home. We were escorted into a large dining area and seated at the head table. The kind woman who had greeted us before told us the children would be arriving soon and then left us alone.

I couldn’t take my eyes off the three-tiered cake that sat immediately in front of us, as well as a wonderful selection of cakes and sandwiches. I immediately started planning what I’d eat first and in what order.

After about ten minutes, the doors of the dining room opened and nurses and children came in. The children were not like the little blonde Woolworth’s girl. In fact, they were very different to her or any other child I’d met. I found out years later that a lot of orphans at Dr Barnardo’s Homes, around this time, were children whose mothers were prescribed Thalidomide during their pregnancies and a few of the other children had hydrocephalus (excessive accumulation of fluid in the brain)

Unfortunately, integration of children with disabilities into mainstream society didn’t exist in those days. As a result, I’d never seen anyone with such severe physical disabilities. Until then, my experience with illness was related to infectious diseases like measles, mumps and chickenpox. As I watched the children who had malformed or absent arms or leg, or whose heads were so swollen and heavy that they were unable to hold them upright, all I could think was that whatever this was, it might be something I could catch. I got scared, really scared.

Soon, the cakes and sandwiches so carefully chosen and admired, had lost all appeal. Despite the kind words of the lady sitting beside me, I couldn’t touch them. I began to think that even breathing the air might infect me. I have no idea how long I sat there before turning my attention to Esther. It was like looking in a mirror. She was sitting, eyes wide, mouth slightly open and very, very still.

I felt myself push my seat away from the table. Esther copied me. I asked permission (as my mum had taught me) to leave the table. The kind lady looked rather surprised as I explained that I wasn’t feeling very well and neither was Esther and that we really had to leave.

I don’t actually remember what we said to the Dr Barnardo’s ladies. I just remember grabbing Esther’s hand and running as fast as I could through the gates and down the lane before stopping, gasping for breath as both Esther and I, tears in our eyes, settled ourselves before walking the rest of the way home.

What did I learn?

Well, not a lot initially, I was just glad to get out of there. I didn’t talk about it very much to anyone, but was very relieved that I didn’t fall ill.

However, as time passed, the enormity of lessons learned hit home. This experience taught me so much about the need for integration and equality across all abilities, the importance of creating truly accessible communities and the role of the charitable sector. More than anything else – I really did learn the need to be ethical when it comes to fundraising. In fact, one of my first conversations with any donor or prospective donor is to make sure I explain my professional code of ethics.

So, that’s my first experience of being a fundraiser. What’s yours? I think we could all benefit through sharing these personal and sometimes powerful stories.

If you’re interested in exploring your philanthropic side and finding out how this can help you delve into meaningful conversations with donors, you may find it helpful to use the guide I developed, Discovering Your Philanthropic Self.