How to advertise for funds off-the-page. Part 1

Papworth’s principles of press advertising Part 1: How fundraising ads work

- Written by

- Andrew Papworth

- Added

- May 01, 2014

Learn from successful campaigns

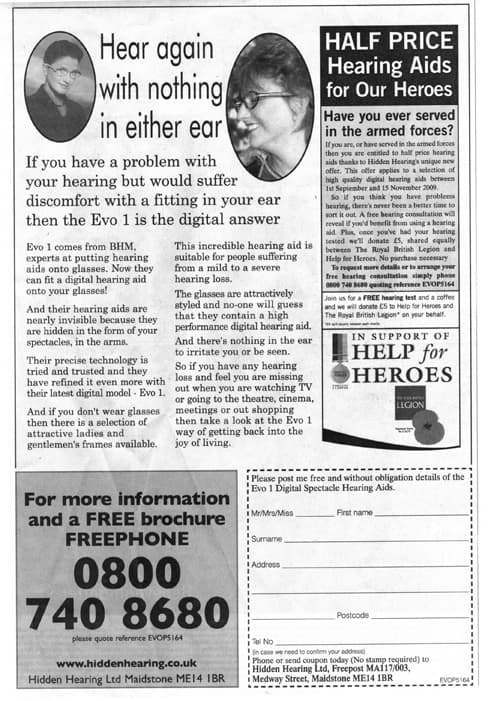

In some ways fundraising advertising is just a specialised sub-set of direct response advertising; so it often pays to look at not only what other successful charities do but also to study the techniques used by commercial companies, which live or die according to the response their advertising achieves. This includes hearing aid companies who attract leads to send to their sales representatives, financial services companies who depend on telephone or online enquiries generated by press advertisements and many other business sectors.

Common factors of successful ads

The best direct response advertisements – including those for direct fundraising – have a number of attributes in common:

- Simple messages with no tricks, which avoid puns, never try to be too clever, don’t use humour, etc.

- A clear proposition that needs the minimum of explanation.

- Relevance to the widest possible audience (unless in strictly niche media).

- They make it easy to respond and offer choices to suit the respondent rather than the back office.

- Uncluttered graphics that work hard to strengthen the proposition (otherwise, no graphics).

- Simple, readable typefaces; avoid white reversed out of black unless you are sure that the type will be large enough and printed sharply enough to be readable; resist the temptation to play tricks with the type because it always interferes with communication. The bit about ‘unless you are sure’ isn’t really an attribute.

- They make sure that the ‘business end’ of the ad – the coupon or other response methods – works and is user-friendly.

There is often, unfortunately, an elaborate game going on between a charity and an advertising agency. The agency feels it has to demonstrate to the charity that it is ‘creative’ – and they find it hard to do so while sticking to the attributes above, even though they seem to work. At the same time the charity feels disappointed at not getting value for money if the agency presents an ultra-simple advertisement that looks – wrongly – as if they could have put it together themselves. Perhaps the answer is to let the agency show it can be ‘creative’, but insist that they produce an alternative which incorporates those attributes associated with success to be tested against their ‘creative’ proposal. That way everybody is satisfied and honour is preserved.

How fundraising ads work isn’t as obvious as it seems

When planning a fundraising campaign using newspaper or magazine advertisements, it is tempting to visualise the millions of readers of the publications in which they will appear. Then to imagine that you will be able to persuade them to respond (whether it’s with a donation, or a sponsorship or membership subscription, or an enquiry about leaving a legacy) by catching their eye with amazing graphics, a smart headline and several paragraphs of moving copy that will convince them of the worthiness of your cause

But life is not like that. It is not fashionable these days to carry out studies of the reading and noting of advertisements in publications but, back in the days when they were commonplace, the findings often gave food for thought, which is perhaps why they are no longer popular with publishers. They involved taking people through copies of publications they had read and asking them to point out the items they had looked at. Typically about 40 to 50 per cent of readers would say that they had looked at an average black and white full-page advertisement in a broadsheet newspaper – and that would include many who had merely glanced at it and turned the page without reading it. When it came to reading the copy the figure would typically be closer to 10 to 20 per cent; for spaces smaller than a page the figures would be very much lower. A typical fundraising advertisement smaller than a quarter of a page in a newspaper might be seen by 20 to 25 per cent and, say, 5 to 10 per cent might read it, on a good day.

Don’t expect to change minds

View original image

View original image

For a newspaper with a couple of million readers that adds up to 500,000 seeing it and maybe 150,000 reading it. When you think that the responses will probably be counted in hundreds, if you are lucky, it means many more people see the advertisement than ever reply to it.

Of course, a lot depends on the inherent interest of the subject matter of the advertisement and the skill of the creators, but the point is that it is a monumental struggle to break through a cluttered environment full of items competing for attention. It is always worth remembering that people buy newspapers and magazines for the editorial and not the advertising – you have to earn their attention in a split second’s scan.

In reality, it is doubtful whether very many people ever have their minds changed by fundraising advertisements. Those who are not already at least partly convinced of the worthiness of the cause are unlikely even to give them more than a glance. It is much more likely that a successful fundraising advertisement just happens to hit someone at the right time – when he or she is feeling relatively affluent and generous or highly motivated – and simply acts as a contact point. This is one reason why some of the least ‘creative’ British advertisements of all time – DEC ads in the wake of disasters, for example – manage to pull in millions of pounds. It is quite possible for a reader to see the same advertisement a number of times without responding, but after seeing it many more times he or she may then decide to respond – though it’s unlikely to be because she or he has thoroughly studied several paragraphs of carefully crafted copy each time.

Most often the task of the good fundraising ad is therefore to identify those who are predisposed to give, to make it clear what is wanted of the reader and to make it as easy as possible for the reader to respond in the way that suits him or her best – and to do it at the lowest possible cost.

Part 2 of this article, on media testing, continues here.

© Andrew Papworth 2010