NSPCC’s Full Stop campaign — a fundraising triumph. Part six: after the appeal

In the final entry on the NSPCC’s phenomenal Full Stop campaign, Giles Pegram CBE reflects on what happened after the appeal and it’s lasting impact.

- Written by

- Giles Pegram CBE

- Added

- March 15, 2018

After the appeal

So what happened after the appeal? First, a bit of history.

The Centenary Appeal

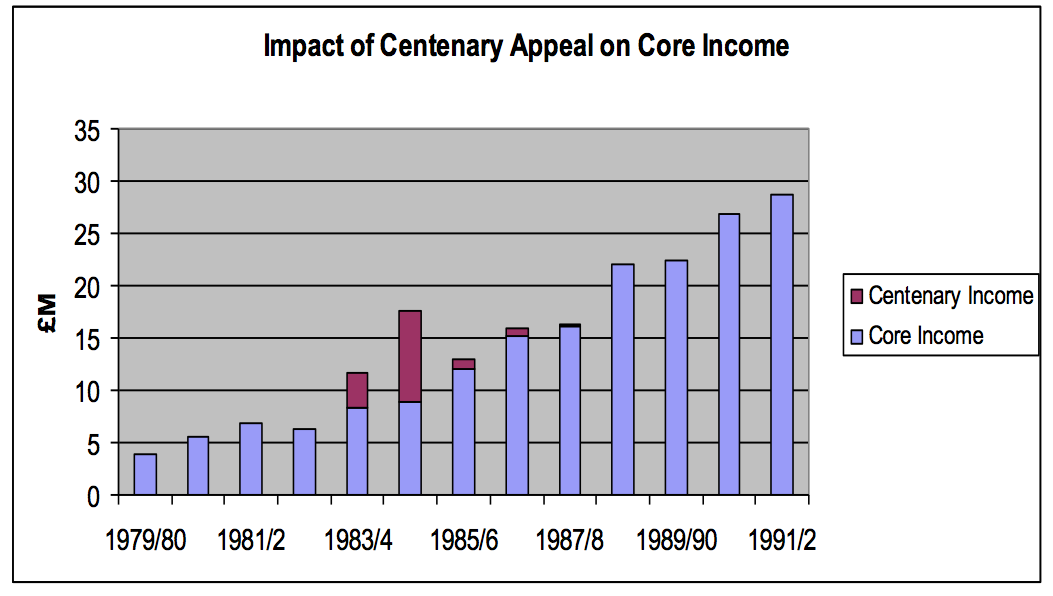

In 1984 the NSPCC launched its centenary appeal, for £12,000,000, at its time the largest appeal in the UK. It raised £15m.

We were worried the appeal might eat into our core income.

- Companies would want the income from their corporate partnerships to go to the high profile appeal. So that source of core income was removed

- We also believed that income from organisational adoptions, challenge events etc. would go to the appeal.

- As would income from major donors.

This is what happened

- Core income increased by inflation from 1979 to the start of the appeal

- Then, despite our fears, it went up during the appeal

- Then, extraordinarily, it continued to go up, way ahead of inflation.

Why?

- Much greater awareness, following a high profile appeal

- New volunteers

- New donors

- New staff

- New ways of working

- A preparedness by the trustees to re-invest some of this success back into fundraising.

So we had some experience when we considered what would happen after Full Stop.

The Full Stop Appeal

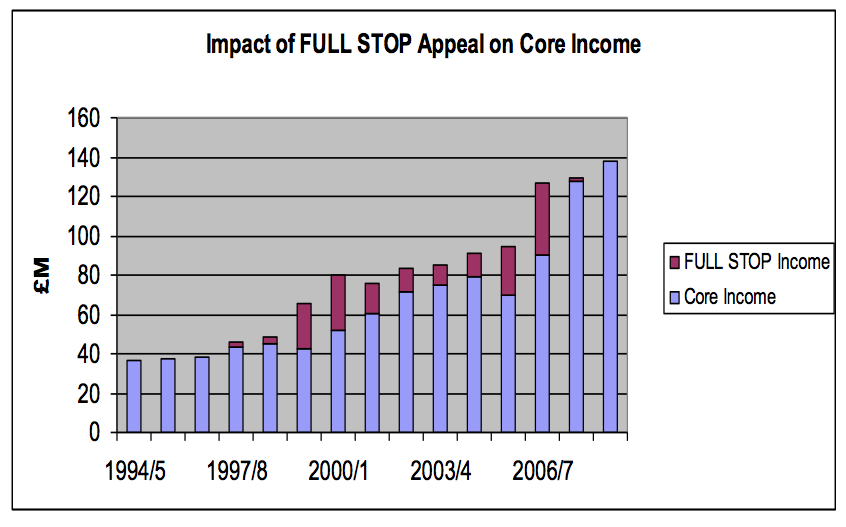

- The appeal income is more complicated.

- As I have explained before, there were too distinct phases; this chart shows that, and the ‘finishing line fever’ I wrote about above.

- But put aside the purple contribution (the appeal) and look at the blue bars (core income.

- Once again, before the appeal, they were keeping pace with inflation.

- Then during the appeal, the blue bars increased way ahead of inflation.

- And in the two years after the appeal, significant growth, as was seen after the centenary.

Again, why?

- Very much the same as for the Centenary appeal. I’ve tried to find differences, and failed.

- Once again, much greater awareness following a very high profile appeal.

- Again, new volunteers.

- Again, new donors.

- And a sense of momentum. Donors had given money to start the process of ending cruelty to children. Having come this far, why would they stop? Although we had not realised it at the time the very proposition 'Cruelty to children must stop. Full Stop' locked people into something long term.

- Again, as I have said, the trustees preparedness to invest in fundraising.

- And this time, something new: the considerably increased investment in recruiting new regular givers.

- Again, new staff.

- And again, new ways of working.

- Despite my reservations, consolidation worked.

What else?

- This time, there was a seismic shift in the way people viewed cruelty to children. Not as something that happened ‘over there’, but as something that had affected them and their families, and which they talked openly about.This was something we had never seen before. We hadn’t expected it, and didn’t know how to respond to it. I don’t know why Full Stop had stimulated it, but it had. We very rapidly had to help staff to deal with ‘disclosure’.

- Our presence in the minds of politicians was never higher, and whilst there was still a long way to go, changes to the law and public policy had given children in the UK unprecedented levels of protection.

- In other words, the Full Stop appeal did not just raise

£274,000,000, it transformed the Society’s core income, its public presence, its work to prevent cruelty to children and its campaigning by supporters. - This was not unexpected, as it was similar to what had happened after our Centenary Appeal, in 1984.

- The Centenary Appeal, and the Full Stop appeal, were instrumental in moving the NSPCC from 15th in the voluntary income league table, to 3rd.

Lessons learned

Was ending cruelty to children possible? Of course not. But was it the right aspiration for the NSPCC in 1999? Yes. At least our donors said so.

The appeal was conceived in October 1995. It was launched in March 1999 and even 3½ years left us very little time before the public launch.

But a word about financial investment.

- February 1996 – Nick Booth and assistant appointed

- 1996 – Prospect research paid for and little else

- January 1998 – Started appointing staff

- March 1999 – Public launch – early gifts

So there was just over a year, January 1998 to March 1999, when trustees had to start to commit to significant expenditure, before cash started coming in, which isn't a long time. Most charities could afford this, if necessary dipping into reserves.

Fundraising has, and will, evolve. (In my view, much of this evolution has been plain wrong, but that’s another subject.) Even since 1999, technology has revolutionised how we live our lives and so has the dramatic increase in media channels. These changes, and many others, will continue in ways we can’t imagine today. But the fundraising principles are fundamental. We have tweaked them, we may have made them deeper but we haven’t changed them. They existed 1,000 years ago and although I can never prove it, I am fairly confident they will still exist in 1,000 years’ time.

We were obsessed with principle, structured but creative thinking, and organised process, flexed to take into account that the external world is chaotic, unstructured and disorganised. The more the external world is unfocused, the more important it was that we as staff remained focused. This was critical to the end result.

There were 3,000 volunteer members of committees and 500 staff supporting them. A completely formal hierarchy would have been bureaucratic and disempowering and conversely a complete lack of structure would have been chaotic. So we created:

- A strict volunteer structure. Very simple and yet invisible to the volunteer

- Staff that gave the volunteers in that structure the best possible support. They worked in teams, within a conventional management structure, but able to work across teams, as was often required.

- A strong volunteer/donor led ethos.

We were constantly under pressure to compromise our principles. At each stage, that might have been the easy answer. Did we? No.

We were often asked to review our target of £250,000,000 and asked whether it was just too high. Did we? No.

The unyielding leadership and dedication of His Royal Highness the Duke of York was second to none and, without doubt, underpinned the appeal’s success. He was a leader who not only led a board of senior volunteers, but also acted as the public face of the appeal. He helped to establish the national appeal board, launched the appeal, and hosted and attended hundreds of events and visited NSPCC projects. He acquired a broad knowledge of the NSPCC’s work and a great understanding of the need for it, having spoken about it with real commitment, both as a father and a supporter.

Since taking over the role as chair of the national appeal board, a quite formidable task given his predecessor, Andrew Rosenfeld took the appeal from strength to strength, helping to ensure that the final push for funds reached its target.

He:

- was committed to the cause, and the appeal, and its target

- was determined not to fail

- contributed himself, at a level that encouraged other significant contributions

- asked others to contribute, clearly and with aspiration

- was a good and motivational chair of each national appeal board meeting

Jon Aisbitt was behind the scenes, but he was hugely influential; a very powerful ally as trustee leading on the appeal. I would urge any charity setting up a major appeal to have such a role.

But were these the real stars? I can’t answer that question. Each supporter was unique. What is certain is that there was a complex web of people with influence, networks and wealth. Each gave of those and equally gave unstintingly of their time. They wanted to do something unique. Each is a star and so I cannot rank them.

The commitment and drive of the executive committee, the national appeal board and its sub-committees, and the steering group which preceded it enabled us to realise, and exceed, the enormous ambition of raising £250m. At the same time, and more important in the long term, it provided the foundations for future growth.

The events that took place during the appeal have had a profound impact. Every home in the UK has been touched by Full Stop and the support amongst the public has given the appeal a lasting momentum that will see support for the NSPCC continue for many years to come.

This story has been about volunteers and donors. Behind the donors and volunteers has been an extraordinary team of staff, supporting the committees, supporting the events and ensuring that every volunteer was appropriately supported and that each potential donor was asked in the right way, by the right person, at the right time, at the right level, for their own contribution. And thanked, recognised and stewarded.

Staff helped volunteers with each action, but didn’t take it off them. Helping them to deliver.

This story may give the impression of order. Indeed there were times when half-a-dozen of us would sit late into the evening working on a puzzle. There were other times of pure chaos and mayhem. Some volunteers and staff were wayward. Much of our time was spent firefighting. There may have been calm on the surface, but underneath the staff were paddling like hell.

The leadership of the NSPCC appeals function management team has been unparalleled and have contributed in an unprecedented way to the appeal’s success. Daily, each manager met previously unknown challenges yet they enabled volunteers, and each one was successful. The culture was: ‘How can we?’, not: ‘why we can’t’. We enjoyed ourselves. On our team were the widest variety of working styles, and we celebrated that diversity, but we all put the donor first. I have not mentioned any, apart from Nick and me but that doesn’t undervalue all the others.

But, and I cannot say this strongly enough, it was the volunteers that did it. The staff were in support. This was real, not notional.

A staff-led appeal, supported by volunteers, would not have been successful.

This wasn’t always comfortable but it was always essential. It required a 90 degree shift. From starting with the NSPCC and its needs, to starting with the donors and volunteers, and their needs for involvement, satisfaction, well-being, enjoyment, and being part of a movement.

Of course, the NSPCC was a large charity, with a strong staff structure, strong income streams and money in reserves. And, of course, we were aiming to raise an unprecedented amount of money. So a smaller charity might read this, and say: “If only… Ah, NSPCC, they’re ‘different’. No, really not. The key principles involved are rooted in history going back hundreds of years. They can be applied to charities both small and large. They need rigorous planning, a refusal to be diverted from focused thinking, and an ethos that is built on the experience of the donor and volunteer, not the ego of staff.

I have asked Ken Burnett to have the final word. Then, I have listed the members of the committees and sub-committees, and the donors who contributed over £100k. When you see them all laid out, it’s quite a list. It started with six people.

The Full Stop Chronicle

All seven parts are linked here for you, now.

- The NSPCC Full Stop campaign, part 1: building the foundations.

- The NSPCC Full Stop campaign, part 2: the launch and beyond.

- The NSPCC Full Stop campaign, part 3: the appeal.

- The NSPCC Full Stop campaign, part 4: final challenges.

- The NSPCC Full Stop campaign, part 5: recognition and consolidation.

- The NSPCC Full Stop campaign, appendix.

- NSPCC’s Full Stop campaign - SOFII’s view.