NSPCC’s Full Stop campaign — a fundraising triumph. Part two: the launch and beyond

Celebrating NSPCC Full Stop: how the biggest ever-public fundraising campaign from a British charity set out to transform child protection. In part one, we saw how the NSPCC laid the groundwork, now comes the amazing story of the appeal itself.

- Written by

- Giles Pegram CBE

- Added

- November 29, 2017

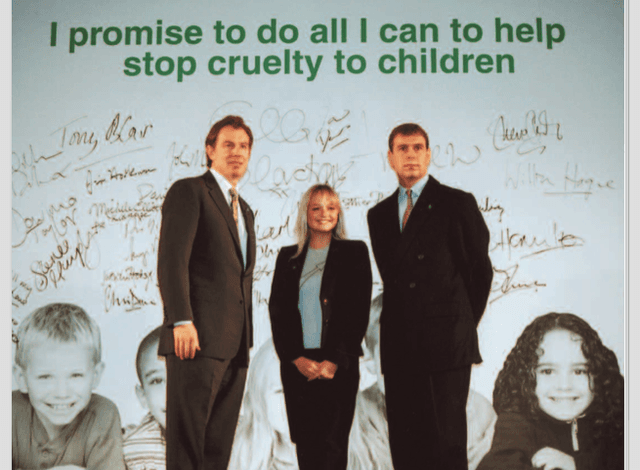

With the executive committee and national appeal board in place, the Full Stop appeal was launched on 22 March 1999 at a high-profile event in London attended by the Duke of York, the prime minister, the leader of the opposition, Lord Andrew Lloyd-Webber and Spice Girl Emma Bunton, amongst a host of stars of stage, screen, music, politics and sport, all at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. During the event, which was introduced by Cilla Black, the NSPCC ‘pledge’ and the Full Stop badge were unveiled. The Duke of York and the prime minister were the first to sign up to the pledge, which read:

'I promise to do all that I can to help stop cruelty to children'

The theatre was packed, the audience was thrilled and the applause was overwhelming. It couldn’t have been better.

But there was no media coverage. None.

The private phase and the public phase

The private phase

Conventional wisdom for major appeals states that you should have a ‘private phase’ where you raise at least 50 per cent of the target from major gifts before you launch to the public. This ensures that when you ‘go public’ there is some confidence that the target is achievable. Chance would be a fine thing.

Much as we would have liked to, there simply wasn’t time for a ‘private phase’. We had to move straight to the public phase and even that didn’t work.

The launch

This was supposed to be the start of the public phase, which meant putting the campaign to end cruelty to children, Full Stop, and the unprecedented appeal to raise £250,000,000, in the public domain, with a ‘wow’ factor because of the launch event.

But there was no ‘private phase’ and no ‘wow’ factor at launch. To say this combination of factors was a disappointment, given how much we had prepared, would be a considerable understatement.

We had overnight to recover and refocus our efforts on the pledge pack.

The pledge pack

On the same day as the launch, pledge packs (in the form of door-drops) were delivered to every household in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, containing a letter from Jim Harding, a pledge card: ‘I promise to do all that I can to help stop cruelty to children’ and three ways for people to sign up in order to get involved;

- Campaign

- Donate

- Fundraise

Another mailing, which included a letter from the Duke of York, was sent to existing donors.

A carefully worded and crafted mailing to prospects was signed by the Duke of York and was a masterpiece of communication from royalty to potential donors. It contained a pen! We never told His Royal Highness. For those in doubt, I would suggest an up-front premium of a pen in a letter from the Duke of York was, at best, questionable.

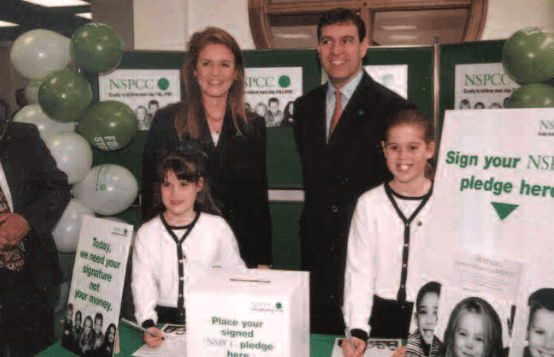

At the end of the launch week there was an awareness-raising activity, the ‘Call to Action Weekend’, which aimed to get thousands of people to sign the pledge. During this weekend, stalls were set up in local shopping centres, staffed by volunteers who encouraged people to sign up to end cruelty to children. The Duke of York, together with Sarah, Duchess of York and Princesses Beatrice and Eugenie, all signed the pledge at Windsor Castle. Leaflets were distributed face to face.

People gave, people volunteered and people wanted to campaign; many wanted to do all three.

In the month following the launch

- Pledge packs were delivered to 23,000,000 households.

- There were 1,500 stalls during the Call to Action Weekend..

- 1,500,000 pledge packs were distributed that weekend.

- 1,000,000 donors and ex-donors were written to.

- As a result, 550,000 people ‘signed up’.

Promotion

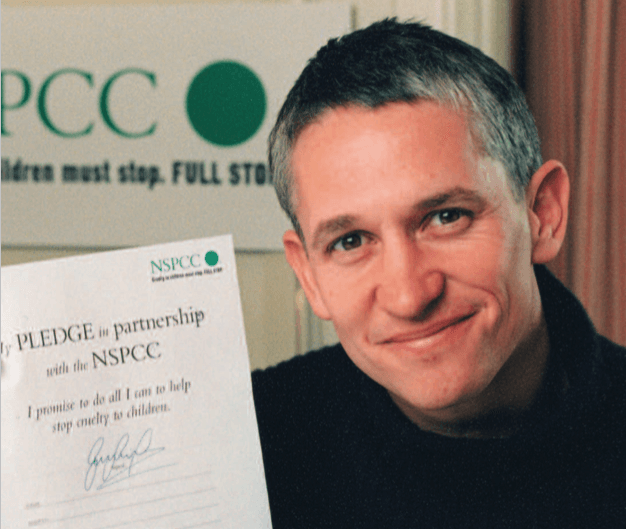

During the previous year, we had saved our advertising budget, our campaigning budget and our donor acquisition budget, then spent them all in the month following the launch. To ensure that our message reached every home in the country, a mass television and billboard awareness-raising campaign sponsored by Microsoft accompanied the launch and lasted for four weeks. It featured former footballer Alan Shearer and girl band the Spice Girls, together with Action Man and Rupert the Bear, all covering their eyes, representing a nation unable to face the shocking reality of abuse. This received considerable media attention.

The campaign was generating an increasing sense of excitement up and down the country. People wanted to be involved in a movement that had such an ambitious and noble aim; the groundswell of support stretched from individual homes and businesses to national sports teams and multi-national companies.

Campaigning: supporters as advocates

People offered to campaign: the pledge attracted a significant number of volunteers who wanted to be partners in campaigning. The NSPCC, by the end of the Full Stop Appeal, had 150,000 partners in campaigning, recruited through the Full Stop pledge, who campaigned and lobbied the government on children’s issues. So successful has this group been that MPs in Westminster voted the NSPCC the most successful campaigning organisation for two years running. Journalists also named the NSPCC the most impressive of the UK’s leading charities. At the end of the appeal, amongst the general public, the NSPCC’s brand awareness and reputation was higher than ever before by far.

(By the end of the appeal, through the partners in campaigning, we believe that the NSPCC had more committed campaigners than any other charity)

The prevalence study

For a more professional audience, the NSPCC also initiated a wide-scale research project into the prevalence of child abuse in the UK. It was the first of its kind to examine child abuse in the UK and its findings, released in 2000, were shocking. The intention was to repeat this prevalence study every five years, to see the long-term impact of the campaign. We might not end cruelty to children but over, say, 25 years, could we make a significant difference? That would be success. I won’t go into the process. It was rigorous. It was long term. And it was measurable.

The Full Stop badge

We created a very simple badge: a green circle, a full stop.

Models, television personalities, singers, stars of the small and silver screen and other high-profile figures helped to raise the profile of the appeal by wearing the Full Stop badge. It was a fundraising mechanism, an awareness device and an incredibly powerful symbol of support.

We got our executive committee and appeal board members to secure high-profile links. (Remember, we were well connected in sport and entertainment.)

We persuaded retail stores, with whom we did not yet have a structured partnership, to sell Full Stop badges.

The public appeal

The popular hymn Abide with Me has been sung prior to kick-off at every FA cup final since 1927. The singer at the 1999 final was wearing a Full Stop tee shirt – the FA cup final is watched by millions worldwide.

Hello! magazine featured Nicole Kidman and The Duke of York on its front cover. The Duke of York’s appearance meant that the message was sent out to a wide audience, featuring on magazine racks across the country. Inside, he set out his passionate belief that cruelty to children can be ended forever

The appeal in the public domain

There was a fleet of lorries carrying the NSPCC logo and a message that cruelty to children must stop.

From train-naming ceremonies in Essex, balloons in Bristol, to a regional reception in Manchester airport and the Full Stop logo lighting up Cardiff’s centre at Christmas, regions all over the country all made a phenomenal contribution to the first phase of the appeal.

The Full Stop logo was featured on buses and boats. It appeared as colours for race horses, projected on to building facades and much more

The Duke of York had always been keen to listen to the thoughts of children themselves and early in the appeal paid a visit to a primary school in time for the One Minute’s Noise initiative. After speaking to the assembly, he listened to the children’s minute of noise, part of a national initiative to encourage adults to listen to children and to get them listening to each other.

During this high-profile early phase, and throughout the appeal, the NSPCC recruited individuals to give £2 per month. The publicity for Full Stop enhanced responses to these appeals and, by 2010, these donors were raising £85 million per year for the NSPCC, the largest single contributor to the NSPCC’s income.

And there was so much more.

Each of these activities was good in its own right. Taken together, they reinforced each other. Many had a fundraising element: we raised a lot of money in this early public phase. But the purpose was noise: loud, repetitive, constant, noise. The aim was to get Full Stop everywhere. And we did. Research showed an exceptional awareness of Full Stop. Starting with nothing.

So, as the public phase progressed, we proceeded in parallel with the private phase. Completely against received wisdom. Yet we discovered that as we approached prospects, potential corporate partners, potential organisational partners, sports’ organisations, the entertainment industry, local trusts and foundations, they already knew about Full Stop, its extraordinary aspiration and the funding requirement.

This worked considerably in our favour.

Support for Full Stop became ‘fashionable’. It was big. It was new. It was high profile. An invitation to a Full Stop engagement event was well received, not binned. (See my section on invitations, later.)

Remember: the idea of an initial private phase was a failure. The launch event, with enormous preparation and organisation, was a failure. But our plan was parallel, not linear.

I believe we achieved things after the launch we simply wouldn’t have achieved if we had followed the ‘private’/‘public phase’ as received wisdom suggests.

We didn’t go against most, well-established principles. This was the exception that proved the rule.

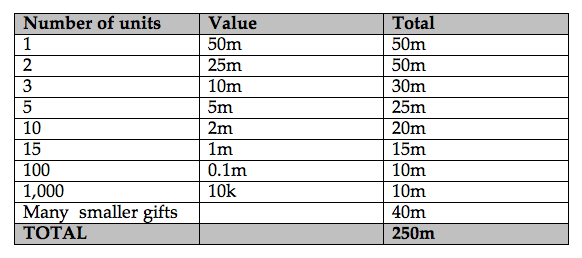

Structure of appeal and contribution table

As has already been stated, the whole concept of the appeal was based on the principle of ‘volunteer leadership’: recruiting volunteers to a national appeal board and sub-committees of that board who would contribute, ask, attend events, hold events, organise corporate partnerships, sports activities, media adoptions, etc and generally back the appeal. They were supported by staff, who did not organise any events themselves. The full success of the appeal is down to the volunteers.

Particular emphasis was that the charity had to adapt from focusing on internal issues to focusing on those issues pertinent to volunteers and prospects. Again, this was a change of mindset. And it was vital.

If volunteer leadership was the key principle of the appeal, the contribution table was the key tool.

The contribution table to raise £250 million reflected many appeals in the past. Conventional wisdom states that the top gift should be one tenth of the total. (In our case that would have been £25m.) We knew that other appeals, in education and the arts, had raised £50m contributions, and we wanted to aspire to this level. So we put £50m as our top gift. (In fact our largest gift was for £30m.) Apart from this, we used received wisdom.

All through the appeal, we knew that 80 per cent of the income would come from 20 per cent of the donors. I will explain in a moment why this was important.

This is the contribution table we used. This needs a word of explanation.

It is evident that if you take out the higher sums projected, you greatly increase the number of lower level contributions that need to be sought. And there is a finite number of sources that you can realistically approach.

In a successful appeal, you will need eight times the number of prospects to the number of contributions projected, of which you may engage four.

In Full Stop, as in most major appeals, most approaches were made personally, face to face, by committed members of the various fundraising groups, so the number of prospects had to be limited, or it would have been beyond the capacity of the volunteers and staff to reach them effectively. Therefore the table is top-heavy.

Too many high level gifts would have been unrealistic. It’s an easy answer, but there simply aren’t enough people who contribute at that level. Appeals with really well-committed committees have failed. Why would you succeed?

Too many lower level gifts would have been impossible to support. More really large contributions have no basis in experience.

This combination of factors determined the contribution table. It wasn’t random.

Why is this so important?

First, it is an indicator to staff and volunteers of the sheer scale of the aspiration and the number of volunteers and staff that will be needed.

We ensured that there was a full discussion of the contribution table at both the executive committee and national appeal board. Not just to be ‘noted’ but a major agenda item. It would have been easy to gloss over it. We forced them to give it serious thought.

If people disagreed, we asked them whether there should be more gifts at the top – and the implications. Or more at the bottom – and the implications.

We wouldn’t allow the executive committee or the full national appeal board to duck the question, and focus on a gala event. We used the contribution table ruthlessly.

Secondly, discussion at the board table set the early levels of giving that acted as markers for those that followed. Once they had tested the contribution table, members of the appeal board and chairs and members of sub-committees, could see where they ‘fitted’ in terms of level of contribution. This greatly helped the process of asking.

Thirdly, as the appeal progresses and contributions changed from projections to successes, gaps in the contribution table indicated at what level fundraising activity should be concentrated.

I cannot over-state the importance of the contribution table and its constant use, especially with the executive committee and the national appeal board.

We would enclose a copy with the short sheaf of papers for every board meeting, showing the same contribution table again and again and again, but with an additional column showing progress.

Five principles

In addition to the core principles, which go back centuries, we developed five, underlying, unusual and very important principles that underpinned the Full Stop appeal fundraising.

Who organises the fundraising?

We decided that the NSPCC’s staff would not organise any fundraising events. Fundraising staff should support volunteers in their activities. This was crucial. If staff had responded to all the ideas coming from volunteers, we would have been overwhelmed. Staff were told not to come up with ‘new ideas’, except when volunteers asked them to help. If volunteers suggested events or activities (they often did), we would politely say: ’That is very interesting. Would you lead it? We will help you set up a committee/volunteer group to support you.’

The only events that we did organise were ’engagement events’, which were high-profile events at Buckingham Palace, St James’s Palace and other prestigious venues where volunteers could nominate their prospective donors to be invited. Organising these was a lot of fun. Events were organised for up to 250+ people. Once again, each invitee was nominated by a volunteer, who would be responsible, with the help of staff, for following up guests – within 24 hours. A great deal of attention was given to making sure that each event was a great occasion for each guest. The venues were proportionate to the scale of the appeal. The principles are universal; the follow up essential.

Double crediting and double counting.

As I have said, the external world is chaotic. Events and activities were organised that involved more than one committee. This was good. It showed that silos were being broken down. So staff would argue about who should be credited. So did volunteers. They would argue about what proportion of the income should be allocated to each: 50:50, or 75:25? This time was completely unproductive. It didn’t raise any more money.

So we devised a system whereby, in exceptional circumstances, more than one committee would be ‘credited’ with all the money. Each committee was happy; so were the staff. Then, at the bottom of the spreadsheet would be a ‘balancing figure’, which took out the double crediting, leaving the figure that was carried forward to the NSPCC’s financial accounts. Double ‘crediting’, but no double ‘counting’. No one notice, no one cared and time was not wasted. Time was spent on fundraising.

Invitations

Invitations? Surely tactics, not strategy? No: the invitation was as important as the event itself.

Invitations to events were of the highest quality. I am embarrassed to say that I supervised the first few personally. The thickest card; an embossed crest that was genuine, not thermographed, the commonly used and cheaper alternative. Often just the NSPCC’s original badge was included. The simplest traditional wording: calligraphed, not just hand-written, names, and envelopes. Nothing ‘clever’ or ‘designed’. Completely unmatched.

Cost-cutters were bemused.

Why? The event would last two hours. The invitation would be on the mantelpiece for weeks or months.

The ‘cheap seats’

I insisted on one thing, which was not popular with some staff and some volunteers, though totally understood by most. Members of the national appeal board sat round the table. The staff that supported them sat behind them, in the 'cheap seats, including me. Apart from the campaign director, Nick, who sat next to the chair. Why? We wanted to emphasise that it was the volunteers who were responsible for raising the target. The staff supported them. Egalitarianism? Not in volunteer-led fundraising.

The trustee leading on the appeal

We knew four things:

- There would be tensions between the appeal board and the trustees. The appeal board would ask: ’Why aren’t the trustees doing more to help the appeal?’

- The trustees would ask: ’Why aren’t the appeal board getting the money in faster?’

- We needed some one who would help negotiate those tensions. We, as staff, couldn’t do it.

- At the same time, I, with Nick, would need a co-conspirator. Someone both a trustee and influential enough to serve as a full member of the national appeal board. Some one whom we could talk to about tactics, next moves and problems.

Jon Aisbitt played those roles wonderfully. He was the treasurer of the NSPCC, a partner at Goldman Sachs and had a fascination with the volunteer leadership fundraising process, about which he previously knew nothing. He became an expert.

Without prompting, and at the right time, he gave at precisely the right level. Not a penny less, not a penny more.

Was he unique? No. Sir Mark Weinberg played the identical role in our Centenary Appeal in 1984. Right down to the timing and level of gift.

Sources of funds

The appropriate sources of funds for any particular charity will be dependent upon an analysis of its strengths and weaknesses. For a national children’s charity, with a highly ambitious appeal, we decided to approach all possible sources. What we ended up with were the following.

- Traditional philanthropic wealth.

- A pledge, fulfilled over a number of years.

- New philanthropists – self-made, multi-millionaires, usually in their early forties, and who were discovering philanthropy for the first time.

- Companies:

- Charity partnerships

- Including staff fundraising

- Promotions

- Sponsorship of events

- ‘Charity of the year’ partnerships

- Donations from company

- Donations from most senior staff

- Charity partnerships

- Local wealth (This is often under-estimated. Existing NSPCC local committees had much better networks than at first seemed. They were not the directors of local companies, or the wealth that exists locally, but they had much better networks into them than we first assumed.)

- Trusts and foundations.

- The prosperous segment (people on a salary that would make them feel that a £100k gift was beyond their means, but who could afford to give £500 a month. Taking into account Gift Aid, £500 a month grosses up to a £100k donation over 10 years).

- High-profile events. (All successful events were organised by committees of volunteers, with significant support from staff).

- A sponsored event, for example the three peaks’ challenge.

- Appeals via the media, using networks at proprietorial and editorial level. (Hence the need for a PR person on the national appeal board and a PR sub-committee..)

- An adoption, for example by Hello magazine, the Society of West End theatres, the Football Premiership, the Rugby Union England team, the TUC, Livery Companies, the National Association of Flower Arranging Societies etc.

- Extra donations from existing donors and regular givers.

- Schools.

- The general public – extra regular giving acquisition at a time of high public awareness.

- The public appeal. During the appeal itself, we ran some staff-organised, public-facing activities, despite our commitment to volunteer leadership. They all failed miserably. The reason there was such a high profile for the Full Stop appeal was a by-product of the corporate, organisational and media adoptions led by the NSPCC’s volunteer networks.

- Other communities where the appeal board and its sub-committees had good networks, e.g. members of the Indian diaspora, entertainment, sport etc. Setting up sub-committees to secure funds in these and other areas was totally dependent upon the networks of the board and its sub-committees. The board was as creative as possible in thinking about sources of funds not listed here.

- Government. In its broadest sense. (Grants that are not tied to statutory contracts.)

In the next installment, we take stock of what we aspired to, what actually happened, and where we were now. And so, what next?

What next indeed? Giles takes us here through the whirlwind of activity that made up the public and private phases of launching the Full Stop campaign. With so much diligent work and exciting ideas, it's no wonder the appeal caught the imagination of the public, leading to the unprecedented success it engendered. In part three, we'll bring you Giles' memories of how the NSPCC consolidated and built on that success. Stay tuned!