RNLI: Britain’s first-ever street collection, 1891

- Exhibited by

- Carolina Herrera

- Added

- September 06, 2009

- Medium of Communication

- Face to face.

- Target Audience

- Individuals.

- Type of Charity

- Community & social services, public/society benefit.

- Country of Origin

- UK.

- Date of first appearance

- October, 1891.

SOFII’s view

Though it took a horrific double tragedy to bring it about, there’s no doubt that Britain’s first-ever street collection for a charitable cause was a significant milestone in the history of voluntary action in the UK and elsewhere. Every tin can that’s ever been rattled in high streets up and down the British Isles owes its provenance to this ‘first’, and the dark events that prompted it. That the public turned out in such numbers and responded so generously to that first street collection is a sign of the very special respect, regard and affection in which the British people hold their lifeboat men and women, the heroes of the RNLI.

Creator / originator

The appeal on behalf of the survivors' families was organised by a committee under the direction of Sir Charles Macara, a prominent Manchester businessman who had a house in Lytham. He appealed to the public to once again give generously, ‘...to this great National Institution which is so sorely in need of funds.’ Sir Charles was astonished to find that before this event, two-thirds of the RNLI’s income had come from just 100 people, who had left bequests or had paid for boats. Macara vowed to make sure that the Institution’s methods of fundraising should change to allow support from a much wider group of people. And thus ‘Lifeboat Saturdays’ were launched.

Summary / objectives

On the night of 9th December 1886 three lifeboats from Southport, St Annes and Lytham were launched in appalling weather conditions to try to rescue the crew of 12 men from the stricken German barque The Mexico. Tragically two of the lifeboats capsized with the loss of 27 crewmen. The third lifeboat from Lytham succeeded in lifting the crew from the barque before it was wrecked off Lytham St Anne’s, Lancashire, and returned them safe to their home port on England’s North East coast. But it was a bitter success, the RNLI’s worst-ever tragedy.

Five years after the notorious Mexico disaster, some concerned individuals got together, formed themselves into a voluntary committee and a plan was conceived to raise money for the bereaved families of the men who died on that fateful night.

Background

From The News of the World, 12th December 1886

‘A distressing catastrophe occurred off the Lancashire coast early on Friday. It seems that during the gale which raged on Thursday a large barque, the Mexico, of Hamburg, from Liverpool to Guayaquil, was seen to be at anchor in a dangerous position off Ainsdale. During the evening she dragged her anchors, and drove on the beach. The Southport lifeboat, Eliza Fernley, was launched about 11 o'clock, and manned by a crew of 16 hands, pulled gallantly through the raging sea in the direction of the wreck, which could be plainly seen by the lights of her signals. Two of her masts were gone, and her crew, lashed to various parts of the vessel, were shouting wildly for help. After a fierce battle with the wind and sea, the lifeboat was seen to get within about 20 yards of the wreck, and her success seemed assured. Just at this moment she fell off with the force of the wind, and before she could be brought up again a terrific sea struck her, and she was capsized, all the crew being thrown into the water. Instead of righting herself, as she ought to have done, she remained bottom upwards, and was blown onto the beach. Three of the crew managed to get hold of the upturned boat and drifted ashore with her in safety; but the other 13 were drowned, three of the bodies being found entangled under the boat when she touched the beach. The remaining ten bodies were washed ashore during the course of Friday morning. Of the 13 deceased 10 were married, and many of them have large families. The men saved were Henry Robinson, John Jackson, and John Ball. The last-named died on Friday night in the infirmary, thus making 14 deaths... ‘

...The story of the disaster is told by John Jackson, one of the survivors. He says that the boat went nicely for a time, but their troubles soon commenced. Captain Hodge and Peters, the second coxswain, were at the helm, and sea after sea washed over the boat. They were beaten back several times, and shipped an immense quantity of water. It was pitch dark and the only indication of the distressed barque was the faint glimpse of a lamp which, as the boat got closer, they saw hung from the mizzen top. Jackson was just about letting go the anchor to get the boat alongside, the vessel being then, he should say, 20 yards from the barque, when a tremendous sea caught the boat right amidships, and she went over, remaining bottom upwards. Some of the crew managed to crawl out. He and Richard Robinson held firmly onto the row-locks and were buffeted about considerably. With some difficulty he got underneath the boat again and spoke, he thought, to Henry Robinson, Thomas Jackson, Timothy Rigby, and Peter Jackson. He called out, "I think she will never right – we have all to be drowned" and heard a voice, probably Henry Robinson's, say, "I think so too". He got out again and found Richard Robinson fairly done. Robinson leaned heavily on his arm, and he thought he must have suffocated. Another heavy sea came, and Robinson disappeared with it and was never seen again. While underneath, Jackson called out to his brother, but could get no answer.

‘Subsequently it became known that a second lifeboat and her crew were lost in the heroic attempt to relieve the same vessel. The signals of distress from the Formby Sands were observed simultaneously from three stations, and three lifeboats put out to the assistance of the vessel. The Lytham boat, the Charles Biggs, although farthest away, reached the wreck first, and rescued the crew, 12 in number, of the vessel. The third lifeboat, Laura Janet, put out from St.Anne's, and as she did not return on Thursday night the gravest fears were felt for her safety. These apprehensions were realised on Friday morning, when the ill-fated boat was discovered at Ainsdale, bottom upward. During the day the bodies of several of her crew were washed up.’

Results

The actual street collection raised just £600 on the day, mainly in pennies. The total given that day was £5,500. The rest came in pledges and supportive gifts, presumably from what we would nowadays call major donor prospects. This was on top of about £30,000 (a huge sum then) which had been given earlier to the fund, within the first six weeks of its launch.

Merits

This exhibit documents the first recorded instance of what was quickly to become an important fundraising classic, the street collection.

Other relevant information

The first collection:

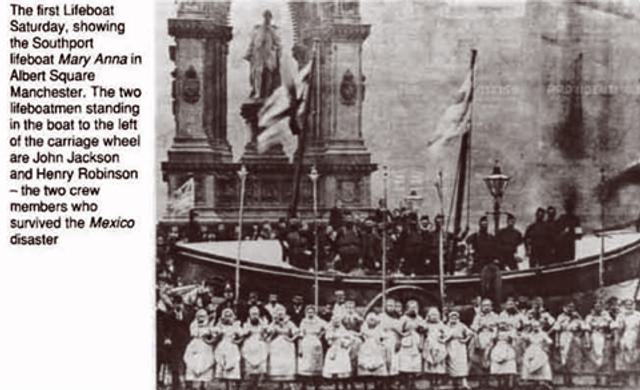

The first ever British street collection was somewhat different from the kind of street-collection events described as such today. This in fact was nothing less than a cavalcade. Crowds turned out in their thousands to throng the streets of Manchester as two real and very heavy lifeboats were physically dragged through the streets on trailers by gangs of local men. As they passed watchers were encourage to throw their contributions into buckets held by members of the procession. The posh folks from the organising committee rode regally in open carriages at the head of the cavalcade, led by a troop of mounted members of the City police force. To ensure that no one missed the opportunity to give, Sir Charles had arranged for several burly lifeboat men to carry sacks on long poles which as the procession passed slowly by were thrust in front of those watching from windows and the tops of buses and tramways surrounded by the throng. Estimates put the crowd at 30,000 people. Sir Charles’s wife organised a special group among the ladies of Manchester, and from this the Ladies Auxiliary Group movement was formed. By the end of 1893 the Lifeboat Saturday had become firmly established as an annual feature in towns and cities the length and breadth of the country.

Final notes

Stuart Bartow sent SOFII a message in May 2011 to say:

The Lytham lifeboat pictured was called the "Charles Biggs" and the "Cox" (pictured) of that boat was called Thomas Clarkson (my great,great Grandfather)!

SOFII’s Once Upon I Wish I’d Thought Of That 2013 – Andy Whyte presents RNLI.

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image