CDE project 1 summary: the use and misuse of language

- Written by

- The Commission on the Donor Experience

- Added

- May 01, 2017

Enhancing the ways we use language

Andrea Macrae and Chris Washington-Sare, April 2017

Reviewed by Matthew Sherrington

Summary guidance

Why think about language?

The language charities use to communicate with supporters, and about them, strongly influences supporters’ feelings about fundraising, about individual charities and about the sector as a whole. Communication with supporters is entirely made up of words and images. Together, words and images are at the core of what charities do and how they work. And yet, across the sector, the nature and power of images – the vividness, the ethics, straight-to-camera gaze, etc. – is scrutinised in much more depth than the nature and power of words.

Often, when language is talked about and thought about, it is in relation to the persuasiveness of appeals. But charities communicate with supporters in lots of ways, from the face-to-face fundraising pitch to the ‘Contact us’ webpage, from the newsletter to the phone call, and from the email sign-off to the annual report. To date, the level of attention most organisations pay to their language use has not matched up to the role it plays in their relationships with supporters. The principles outlined below, and detailed more extensively and with examples in the full project document, offer simple ways of developing language use to improve supporters’ experiences of communications and of charities more broadly.

Nine key strategies to enhance the ways we use language

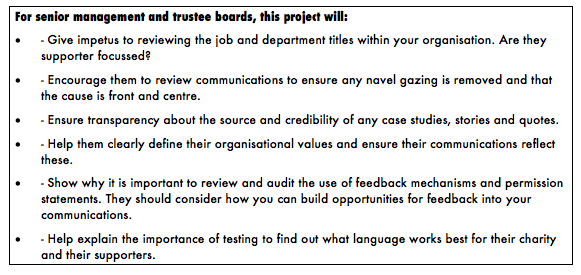

1. Rethink language to reflect, respect and engage with the views and feelings of supporters.

The words we use reflect the way we think. Charities can develop their use of language to better focus on, respect and ingrain the values, views and feelings of supporters. The most effective way of achieving this is by fundamentally reorienting language to more directly reflect supporters’ perspectives and interests. Charities can embed this approach at all levels of the organisation. Consider the implications of department names, and how they can be reconfigured to reflect and instill a supporter-centric approach.

For example, a department name such as ‘Donor Acquisition and Retention’ reflects a fairly de-humanising approach to supporters. It seems to prioritise supporters’ monetary value in a cold and clinical way. Something like ‘Supporter Development Team’, on the other hand, recognises the supportive nature and value of an individual’s relationship with the charity beyond the financial transaction, and suggests that there are options in the ways the supporter’s relationship with the charity can evolve (rather than them simply being ‘retained’).

Do a thorough ‘orientation check’ of all internal and external language. Wherever language could be more supporter-centric, recast it to align with and reaffirm supporters’ viewpoints and interests.

This is more than just semantics: language use reflects and reinforces attitudes and behaviour. Ensuring your organisation’s language expresses a supporter-centric approach is a key step in ingraining support-centric behaviour. Most of the recommendations made by this project stem from this essential principle.

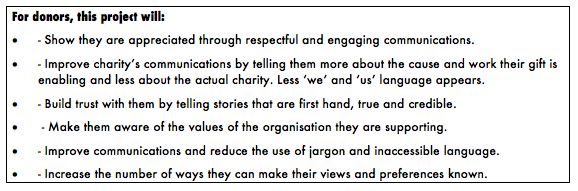

2. Talk less about the charity and more about the cause, the work, the beneficiaries and the supporters

Too often, the charity itself takes centre stage, dominating too many sentences through too much talk about ‘us’ and what ‘we’ do or have done. Lots of evidence suggests that supporters are primarily interested in the cause and in the people, animals or things at the heart of the impact. Let supporters hear from and about these people and things: these should be the main focus of communications and should take up the most words, either as the topic or the speaker. The charity itself is important – it is the charity that the supporter develops a relationship with – but the cause and impact tend to be of more interest and personal relevance.

The wealth of data on this issue is convincing, but you can do your own supporter surveys and background and foreground different people and things according to their feedback. Generally, though, it is good practice to avoid accidental (or deliberate!) organisational egocentricity.

3. Communicate authentic content with honesty.

Authentic, first-hand reports can be very powerful and can offer supporters a real connection with the cause. Sometimes charities use invented case studies, stories and quotes. Though this is sometimes for good reasons, it can make readers suspicious of being manipulated and can undermine the credibility of a message. In the current context, this is a particularly risky strategy.

Where fictitious examples are necessary, transparency about this is crucial to avoid alienating supporters and to prevent further damage to the sector’s reputation. An honest, open explanation and justification is easy to include, and it can even help communicate some of the problems at the heart to the cause. Use real stories where you can, and be transparent about any invention.

4. Communicate values, and do it consistently.

Evidence suggests that supporters feel more positively towards a charity, and feel more satisfied by its communications, if the charity clearly communicates its values, ethos and identity. Develop a coherent ‘voice’ for your organisation. Generate ready-to-use phrases expressing core propositions, mission statements and standard descriptors. Create guidance on a ‘house style’ with examples of tone of voice. Use every communication with supporters as an opportunity to reflect and reaffirm your values.

5. Subvert expectations.

The formula of the charity appeal is so familiar to supporters that many feel they don’t even need to open the envelope, or the email, to know pretty much exactly what’s inside. Of course, the formula hasn’t arisen over the years simply through custom or accident: trial and error has allowed the sector to hone in on some basic features and structures which work well. However, familiarity breeds boredom and disengagement. Charities need to surprise supporters, to grab and keep their attention, with unusual, innovative communications.

Charities can productively exploit the conventions of the sector’s communication styles, and the norms of their own organisation’s specific tone of voice, by occasionally, tactically and playfully deviating from them. Several charities have had great success with innovative product names, mail formats and campaign settings and styles. Adding some more creative and attention-grabbing messaging in amongst the more conventional communications can surprise and delight supporters, reignite interest in the cause and reawaken allegiance to an organisation.

Links to CDE project 12 – Inspirational creativity .

6. Use inclusive, accessible language and avoid jargon.

Ensure the language of mass communications is simple and jargon-free. Using long words and complex sentence structures can sound impressive, but it tends to unnecessarily cloud meaning. Short, simple words, sentences and paragraphs are the most effective means of getting the message across to the most people. Even in more conventionally formal kinds of communications, like annual reports, data protection information, and details of how to make a complaint, accessible language conveys meaning more easily.

In any text which is made available to public audiences, it’s also a good idea to avoid using internal jargon (such as ‘acquisition’, ‘product offering’, ‘upgraded’, etc. within fundraising). Jargon is convenient for efficient communication within an organisation: it is not designed for public communications, and it is often impersonal and obscure. If the public forms even just a small part of the audience for a text, make sure the language is totally jargon-free.

Likewise, avoid expressions which might be hard for some members of the public to understand. Metaphors – even ones which have become part of everyday expression, like ‘on the same page’ and ‘change your mind’ – can be confusing for those for whom English is an additional language. Keep language as simple and literal as possible.

See CDE project 11b – Direct mail and project 11c - Digital

7. Invite feedback and turn it into dialogue.

Most charity communications are one-way, talking at or to supporters, with no space or invitation for a response beyond a donation. The act of inviting feedback, input and response is crucial for a healthy, well-functioning and informed communicative relationship. How can a charity really know what works for its supporters without explicitly and regularly inviting supporters to communicate with the charity? There are many ways of effectively and efficiently building an invitation for dialogue into communications. The simple act of asking for supporters’ views helps to convey respect for those supporters and enhance their relationship with the charity.

Asking for feedback is the first step. Receiving and processing the response is the second. Third comes explicitly acknowledging that response, and communicating back in turn, addressing the topics and issues raised. Thank supporters for their comments. Take up their topics and use their language. Demonstrate that you’re listening and that you care about and value their input and views. Develop a genuine dialogue with supporters to learn precious insights, enhance their experience and strengthen their relationship with the organisation.

See CDE project 3 – Satisfaction and commitment, project 11 – Communication with individual donors and project 13 – Giving choices and managing preferences.

8. Make contact permissions options work for supporters

The permissions statement is a contentious area. Public concern about use of personal data, and about receiving lots of unwanted communications, has been a big part of recent criticism of the sector. Permissions statements can feel fraught with tensions. These agreements, though, can be used as a constructive means of developing the supporter-charity relationship. Careful wording and management of permissions statements can turn them into tools for developing trust, showing respect for supporters’ preferences, and explaining the ethos and rationale of the charity’s communications.

Each option should be explained in clear, simple language, enabling supporters to make informed choices that meet their needs and shape their expectations. Permissions statements should also include details of the kinds of communications a supporter can expect through any particular channel, the advantages of each kind of communication, and how often those communications are likely to be received. These simple steps can make all the difference to a supporter’s satisfaction with future communications, and turn the ‘opt-in’ into a message about shared values, choice and mutual respect.

Links to CDE project 13 – Giving choices and managing preferences.

9. Test your communications to find out what works best for your charity and your supporters

The charity sector excels in effectively testing inserts and images. Language is just as testable, using many of the same, simple methods. Lots of different elements of language are worth testing in different communicative contexts, including the use of an opening question, the phrasing and placement of the call to action, etc. A lot of assumptions about language in charity communications lack sufficient evidence, and many common principles need to be adapted to specific contexts (i.e., individual charities, different channels of communication such as email or letter, etc.) to be effective. Through careful testing with different supporter groups, charities can really understand what works well for their charity, with their supporters, and why.

A final word

Language use may just be one part of the supporter experience, but it is a hugely significant part. Very little of the communication between charities and supporters is not dependent on words. If a charity’s language use is careless or ill-considered, it can drastically undermine the effectiveness of the charity’s work. Language is too central to the supporter-charity relationship to ignore.

The principles outlined here are the essentials of good practice. These principles guide you through a re-examination and reconfiguration of core elements of communications to enhance supporters’ experiences. Each of these principles can be taken far beyond the basic outline provided by this project for even greater effectiveness, but this summary provides a strong foundation from which to start.

Context

This project gathers, shares, and seeks to develop good practice. It proposes nine evidence-based recommendations, each designed to help charities develop language and communication practices to swiftly, simply and significantly improve the supporter experience. The recommendations are illustrated through case studies demonstrating ways in which ideas such as these are already making a positive difference within the sector. The recommendations and their explanations are intended to provide inspiration and indicative models which can to be taken up, explored, applied and adapted to different contexts.

Summary methodology

This guidance was developed on the basis of insights gained through two main methods:

1. A series of research interviews with senior figures in fundraising, supporter engagement and communications consultancy services across the charity sector.

2. Research investigating and reviewing the methods and conclusions of relevant academic and sector publications (e.g. reports, surveys, studies, experiments, and articles) related to issues of language use in charity communications.