NSPCC’s Full Stop campaign — a fundraising triumph. Part one: building the foundations

Celebrating NSPCC Full Stop: how the biggest ever-public fundraising campaign from a British charity set out to transform child protection.

- Written by

- Giles Pegram CBE

- Added

- November 21, 2017

SOFII is privileged to tell the story of the most successful campaign in British fundraising history: the NSPCC’s Full Stop appeal. Launched to coincide with the millennium, the Full Stop appeal had a bold and stretching ambition: to eradicate cruelty to children in Britain. An unachievable goal perhaps but by taking such an audacious approach they raised more money than had ever been thought possible and set the standard for a successful appeal.

Introduction

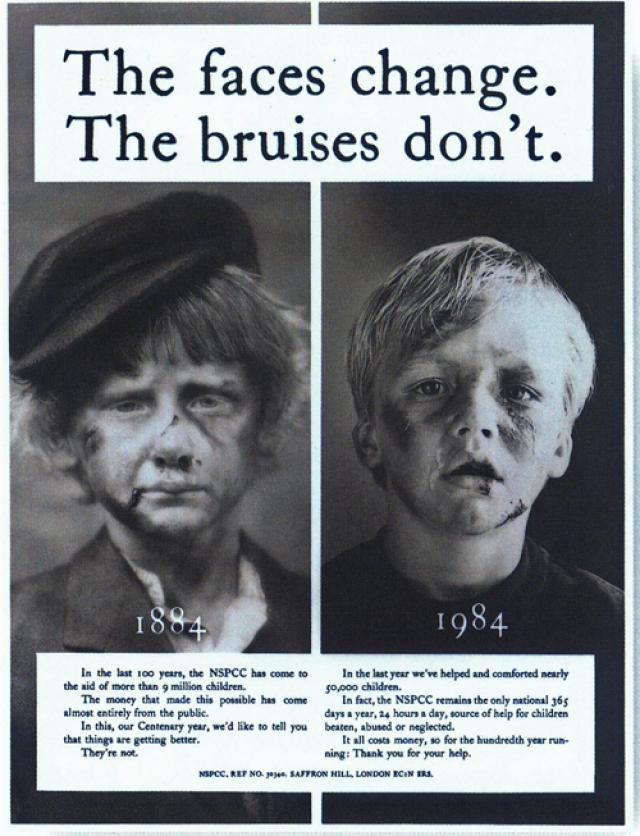

The National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was fortunate to be able to take inspiration from its own history. In 1984, they had launched a special appeal to coincide with the organisation’s centenary anniversary. When they launched this special appeal the NSPCC was well-respected and honoured, but even so its annual income was a mere £3 million. But in Giles Pegram, their young director of fundraising, they had someone willing to dream big.

You can read all about that dream for the centenary appeal here.

It was with this success in mind, one that transformed the fortunes of the NSPCC, that Giles Pegram approached the millennium campaign in the mid-nineties. What follows is an account of this bold and innovative campaign from start to finish in Giles Pegram’s own words.

This story is about old-fashioned, volunteer – not staff-driven – fundraising. It is about connecting donors to the cause, not about fundraising technique. It is about long-term thinking: four years of planning before any income was received and giving donors and volunteers as brilliant an experience as we could.

Of the staff, in this article I only mention Nick Booth and me. Nick’s contribution as campaign director was unique. He joined the NSPCC as a graduate trainee and rose through the structure.

Of the others, I would mention Angela Cluff and Tim Hunter. Nick was public facing. Angela, Tim and I were, to most volunteers and donors, practically invisible.

Did we do anything wrong? Certainly, all the time. Of most significance was that we didn’t do enough to cement the long-term involvement of individual donors and volunteers. We were, I believe, good at recognition. And, yes, we had a consolidation plan for the whole appeal. But we should have invested more in reporting back to each donor about what their individual contribution had achieved and stewarding them thoroughly. We should have ensured that we had a plan for each donor to cement their involvement in the long term. This wasn’t just negligence. It would have taken a lot more resource than we gave it. We should have given more time to this in early planning. You will see later that consolidation worked. Big time. But it could have been better.

This piece is a narrative that starts at the beginning and finishes at the end. Intertwined are the underlying principles. The story is about the NSPCC but the principles are universal and could be applied to any charity, large or small, thinking about a transformational major appeal.

The following piece is quite long. I have edited it ruthlessly, helped considerably by Joe Burnett. There is, in my view, nothing in here that shouldn’t be. And I hope I have covered everything important. Please enjoy it. If you are seriously considering a major appeal, please read it thoroughly. Twice.

Giles Pegram CBE, February 2017

Part one - Aspiration and target for the appeal

On Wednesday 25 October 1995, the senior management team of the NSPCC went to Chichester for a two-day brainstorm. The purpose of the meeting was to start to think about what the NSPCC should do to mark the turn of the millennium. We believed that it was a time of change, looking back on the last 10, 100 and 1,000 years and looking forward to the next. We thought we should be looking for something bold and transformational to mark the thinking at that period.

After some initial banter, Jim Harding, then chief executive of the NSPCC, said:

'We are the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. If we are really to live up to our name, our ultimate ambition should be stop all cruelty to children.'

We were flabbergasted. Did he really mean it? He cited a document that had been produced a year earlier, a review that the NSPCC had commissioned that had concluded that almost all child abuse could be prevented, if the will to do so was there.

After we had discussed this for some time, Jim Harding turned to me and said:

'If we were to launch a campaign of this magnitude, how much money could you raise in addition to your normal income? '

I stopped and thought. One of the largest appeals to date had been by The Royal Opera House, for £100 million. Surely ending cruelty to children was worth more than that? At the other end of the spectrum I thought about £500m, but that simply was not credible – remember this was 20 years ago. So, I settled on £250 million and fed that into the thinking. The number had no basis in reality.

Today, we talk about ending poverty or finding a cure for cancer. But in 1995, the idea of ending cruelty to children was an aspiration unheard of. Society didn’t end things, it changed them, improved them, made things better for individuals.

It also set an unprecedented challenge for the NSPCC’s fundraisers – how would they be able to support such a goal? A major appeal on top of the NSPCC’s normal income would be both justified and required and the proposition for the Full Stop appeal, which would aim to raise £250m in one year, was made

No other charity had achieved, or even attempted, the goal of raising so much money. However, the NSPCC believed that it might just be feasible. When the NSPCC organised its Centenary Appeal in 1984, its annual income was £3 million. The Appeal raised five times that amount: £15m. Before the Full Stop Appeal, our annual income was £50m, so an appeal for five times that, £250m, seemed almost feasible. Another factor that convinced the NSPCC that such a goal was not insurmountable was that, although no conventional charity had raised similar sums, academic institutions such as the universities of Oxford and Cambridge had successfully secured comparable overall totals and significantly large sums from individual contributions.

The morning after

The morning after the brainstorming session, I brought my senior management team together at 9.30. I told them of the thoughts and discussions. I told them of our aspiration to end cruelty to children. I told them of the £250,000,000 appeal that was down to us. I told them we might not raise it. I told them I didn’t know how we were going to do it – that would be down to all of us to work out. But the target was non-negotiable, only how we set out to achieve it was.

Nobody dissented.

An hour later, we called together all fundraising staff in the National Centre. We gave them the same message meaning everyone in fundraising heard the same message, from the same people, at the same time. Many of the staff were genuinely enthusiastic and welcomed such an exciting challenge. Others were neutral and it would take a while for it all to sink in. There were two naysayers, who said we could not possibly succeed and would damage the NSPCC’s reputation when we failed. We didn’t dismiss their views, which people respected. One continued to be negative throughout the appeal, but no one took any notice. He was good at his job, so we didn’t want to let him go. If anything, he grounded us in reality.

There was no conference, break-out groups, flip charts or post-it notes. When Henry V said:

‘Once more unto the breech dear friends’,

he didn’t follow on by saying

‘or not, let’s break out into groups to discuss it.’

(By the way, I am in no way comparing myself to Henry V.)

Leadership theory

It was rapidly acknowledged that, in order to reach such a target, a different approach to the incremental growth strategy traditionally applied by charities was needed. The volunteer leadership principle of fundraising was recognised as the only concept that would enable such a sum to be raised. This is the way almost all major appeals in history have worked: in his book Foundations for Fundraising (ICSA Publishing, UK, 1995), Redmond Mullin gives a detailed account of the re-building of Troyes Cathedral around 1400, the time of the battle of Agincourt. Closer to home and the present, this is the model we had used in the Centenary Appeal 15 years earlier.

In this model, the responsibility for raising funds is transferred from the charity’s staff to a group of senior volunteers or ‘leaders’. The ‘appeal board’ owns the overall target, with sub-committees of the board owning different portions of that target. The role of the charity’s staff is to support the volunteer leadership of the board and its sub-committees in reaching their targets. This is key.

Each member of a volunteer leadership group needs to meet three criteria. They need to:

- Be influential and committed to the appeal.

- Contribute according to their means.

- Be prepared to ask others to contribute.

At this stage, it is worth noting that the word ‘contribute’ had a very specific meaning. I’ll come back to that later

- No ‘advisory groups’.

- No ‘fundraising sub-committees of the board of trustees’.

- As the Americans say: give, get, or get off.

This required a significant change in culture for fundraisers within the NSPCC. They had been used to working to budgets, individually, in their teams and across all fundraising.

Volunteer leadership required that the volunteer committees owned the target and the job of staff was to help the volunteers achieve their targets. This cultural change was indescribable. This was a really challenging mind-shift. It took time, departmental away-days, tensions and the management time resolving those tensions. We were asking people to reorient fundamental views.

Early phases, including trustees, establishing a steering group, leading to the national appeal board

Between October 1995 and February 1996 the chair of trustees was swiftly brought into the discussion. A paper was produced that went to the trustees on 15 February 1996, outlining the aspiration of ending cruelty to children, the aspiration of a £250m appeal and the change that would be needed within the NSPCC to achieve this.

It was clear that the trustees were not going to agree to such a fundamental change after one meeting. So, we asked them to agree to a one-year feasibility study into the idea of ending cruelty to children and of raising £250m in addition to our normal income.

After discussion, they agreed and decided on a small budget for the process.

I was able to immediately appoint a director for the appeal. Nick Booth was an ideal choice. As a local appeals manager, he had organised several centenary appeals for local volunteer branches, so was appointed as campaign director, moved to London and appointed an assistant. For the next year, he and his assistant were the only people dedicated to driving forward the feasibility study for an appeal. The rest of us worked on the appeal in addition to our day jobs.

NSPCC’s networks.

The NSPCC had thousands of volunteers working within its local branch and district committee structure and, because of that, it was estimated that there was just two degrees of separation between the NSPCC and most people in the country. Due to the strength of this volunteer network, the charity was confident that it had access to most influential and wealthy people in the country at that time.

But it was not sufficient just to have access to influential people, it was also necessary to get their commitment to the Full Stop appeal.

So we consulted widely. We talked with many of our most influential and wealthy donors, our corporate supporters, our trust supporters, groups of our branch and district supporters. And individual givers. We tested the hypothesis of £250,000,000 with them. We asked them whether we were right to pursue such an aspiration. We didn’t lead them to the answer: yes. We wanted the truth and the resounding response was: yes – go for it.

People viewed the appeal as an opportunity to get involved in a radical new initiative. The sheer scale was motivational: people wanted to be associated with something big, particularly as the millennium drew closer.

In addition, the moral imperative was crucial. How could people turn down the opportunity of getting involved with something as important as ending cruelty to children?

Of course ending cruelty to children wasn’t possible, but it was the right aspiration.

Prospect research

Satisfied that the appeal was achievable, at least in theory, the NSPCC began the largest programme of prospect research ever carried out in the UK, with the aim to locate all potential sources of income. Between April and December 1996, using a range of techniques and the two major ‘prospect research’ firms at the time, analysis was carried out that considered not only how wealthy people were, but also how much they had given in the past and their propensity towards charitable giving. This was relatively new thinking at the time.

Key findings from the prospect research:

- 100 UK individuals worth at least £100 million.

- 316 individuals, companies or organisations that had given or raised at least £1 million.

- 581 individuals or trusts with the potential to give at least £1 million, some of whom might never have donated at a significant level before.

- The number of millionaires in the UK had doubled in the last five years.

And not just the numbers, but also the names. It was estimated that this was still only 10 per cent of the potential number of wealthy individuals NSPCC could have contacted.

The trustees’ decision

After a year of research, discussion and thinking, by March 1997 we were ready to present to the trustees and, on 12 March 1997, we started a two-day brainstorm with them. We knew who our allies were and we knew the naysayers. Even after a year, the majority still needed to be convinced. Looking back, this might seem inexplicable after a year of discussions, but you don’t agree to end cruelty to children between discussions on the accounts and any other business.

We made the proposal that we should go ahead. Each one of the NSPCC’s senior management team in turn gave clear, crisp, yet also rounded, presentations. We had time, which we never usually had at routine meetings. We needed to put things in a way the trustees hadn’t heard before. A lot of work had been done to present our findings to them, to give them the opportunity to ask questions, through break-out groups and so on. It was a demanding two days.

Towards the end of the second day, staff were asked to leave and we then had the most agonising hour of our lives. Looking back, it can’t have been much easier for the trustees either. Eventually, we were called back in and told that the decision was affirmative: we should go ahead.

We were ecstatic.

At the next meeting of the trustees, there were still naysayers. Our treasurer, Jon Aisbitt, whom I will mention often, said: ‘The ship is about to leave harbour. If you’re not ready for the adventure, please get off now.’

The next step: setting up the steering group.

We had a reception at our National Centre with about 150 key friends and societal thinkers to help us explore this remarkable ambition and to understand whether this level of engagement could be achieved. Jim Harding gave a speech that positioned them on the inside track. Should we do it, would they support us? Their answer, again, was a resounding ‘yes’. The children of the United Kingdom deserved nothing less. We now had a core group of supporters for the Full Stop aspiration.

We had decided that, rather than appoint a chair and then build an appeal committee around him or her, we should follow a two-stage process: we should set up a ‘steering group’ of our most influential contributors to get them to test both the reality of our plans for working to end cruelty to children and the achievability of the £250m appeal. Then we would set up the appeal board.

After internal work during April and May 1997, we were given a date, 10 September 1997, when our president, Princess Margaret, would hold a small reception in her private apartments at Kensington Palace, with a view to setting up the steering group.

Key staff agonised many hours, over many days, over whom to invite. Each prospective invitee was put under a microscope. If we invited too many, we might lose control. If we invited too few, we might not achieve a critical mass. How would they interact? If the social dynamic was wrong, they might descend into chaos. But we also wanted people who were really powerful and had strong minds.

We invited maybe 20 of our most influential donors. It would be an understatement to say that not all of the individuals invited were convinced about either the aspiration to end cruelty to children, or the possibility of raising £250m. Members of staff weren’t invited to the event. This was an event where we could only influence proceedings from afar, although we had a plan, as best as we could. We persuaded one invitee to ask a specific second invitee to chair the steering group, if one was agreed. We prepared and briefed as well as we could. But it was all down to how the relationships between the volunteers worked on the evening.

So on 10 September 1997 Nick Booth and I ensconced ourselves in the bar of the Kensington Palace Hotel, saw the limousines arrive, ate bar snacks and then saw the limousines depart. We already had a ‘trustee leading on the appeal’, Jon Aisbitt, then a partner at Goldman Sachs, i.e. a trustee who believed in the vision and the target for the appeal and was a co-conspirator with us on the progress of the appeal. We waited.

Finally, he joined us at the hotel. The steering group had been agreed, a number of people had agreed to serve on it and George Magan, a banker and financier, had agreed to chair it. This was exactly what we had wanted.

We ordered a bottle of champagne, which we paid for, of course.

The first meeting of the steering group.

With the pressure on diaries between October and December 1997, we were not able to have the first meeting of the steering group until January 1998. We started to recruit a small number of staff who would be necessary once the steering group had started its discussions. A small number at first, but it increased as the appeal gathered momentum.

The first meeting of the steering group was held at the Berkeley Hotel at 8.00 am on 8 January 1998. Seven members of the steering group turned up and the meeting was awful. I have never felt so belittled. The members of the steering group challenged the aspiration to end cruelty to children, challenged the size of the appeal and challenged the competence of the NSPCC to deliver what was necessary. Challenge after challenge, question after question. It was a very tense meeting and I don’t remember a single positive thing being said.

At the end of it, everyone was delighted and kissed each other on both cheeks before leaving in their limousines.

I drove Jim Harding back to the office. He was devastated. He felt that his aspiration had been demolished. It was all over.

I explained to him that seven multi-millionaires would not come for breakfast at eight o’clock in the morning for blood sports. They were strong supporters of the NSPCC, had each made very significant gifts. They wanted the NSPCC to succeed. Needless to say, all the actions were with the NSPCC.

The next meetings of the steering group, January to June 1998.

I will not go into the detail of every meeting of the steering group. Suffice it to say that they met monthly from January through to June 1998, wanting to see the plan. But, as the steering group for the appeal, they wanted to test the £250,000,000 and the numbers behind it. Test, reflect and test again. They were being asked to put their names, reputations and cash to £250,000,000. This would be what they would encourage their friends, on the national appeal board, to own with them and ultimately all persuade their friends to contribute to. Each had been involved in, or responsible for, very major appeals, but this was of a different order of magnitude. Why should they come out of their comfort zone? At this point Jon Aisbitt was the NSPCC’s treasurer and as a Goldman Sachs partner, numbers were his business. He worked with our finance director to produce all the numbers and bullet-proofed them thoroughly. At each meeting, he would present all the figures and be grilled by the steering group.

It was a real battle of the giants. Jon was himself a very influential figure, being a partner at the world’s leading investment bank. At one point, after a very brutal grilling and with a little frustration, he reminded the members of the steering group that he was ‘the honorary treasurer’!

Jon R. Aisbitt

Transforming the NSPCC.

Meanwhile, the Society was working on the plan to change our organisation so that we were concentrating on activities that contributed to ending cruelty. And spend the £250m. We needed a plan, before the national appeal board started work on raising the £250m. Jon Aisbitt, who, as treasurer, was chair of the finance committee, didn’t think we were working hard enough and his own credibility was on the line, having been so robust with the steering group.

He changed sides. At one point, in the middle of a finance committee meeting, he said we had six weeks to produce a plan and that he could no longer help us. He stood up and quietly walked out, leaving all the other members and the supporting staff in silence.

We re-grouped by approaching our auditors to have three staff from Deloitte assigned to us full time. Jim set up a group of 10 senior staff to meet for a whole day every week. Total focus.

We argued, we debated, we researched and we consulted. After six weeks we produced a detailed plan to start to end cruelty to children that was two inches thick, with a readable, but thorough summary and detailed financial plan.

The conclusion of the steering group.

I cannot recall any six months during which I had to work so hard. Nor when the NSPCC responded so well to the external pressures.

Every member of the steering group attended almost every steering group meeting over an intense six months. By June, they had been convinced of the ambition to end cruelty to children, the plan to take that aspiration forward, the budget and of the viability of the £250m appeal. Almost all of them were so motivated that they agreed to form the core of an appeal board. They changed from being our most vocal critics to being our most powerful advocates.

At this point, in June 1998, their main focus became finding a chair for the appeal.

A lot of volunteers had been engaged at this stage. Having been through agony the steering group wanted to get started. We heard, through a mutual friend, that the Duke of York was quite interested in the appeal. Unfortunately, he, together with the rest of The Royal Family, decamped to Sandringham in July 1998 and he did not respond to messages.

The suggestion was made that one of the steering group members, Sir Mark Weinberg, financial grandee, strong supporter of the NSPCC and close to the Royal Family, should go to Sandringham and camp out until he got an answer. After consideration, that idea was rejected.

On 16 October, whilst I was at the International Fundraising Congress in Holland, I heard, by phone from Sir Mark, that the Queen had said that the Duke of York would chair the appeal board. Once again, we were ecstatic. We could not have imagined a better chair for the appeal than The Duke of York – fourth in line to the throne, with impeccable credentials and two children of his own – who would be a fantastic draw. It was hard to make small talk on the coach back to the airport.

Nick Booth and I had lunch with him on 29 October 1998 and agreed that there should be an executive committee of key volunteers and a national appeal board that was much larger.

The executive committee would meet each fortnight at Buckingham Palace. The national appeal board would be larger and meet every three months.

Through all of this time, we knew that we had to launch in March 1999, so we had five months to put in place the structure for the appeal. We wanted to use the millennium and had booked the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. We were in the diaries of the Duke of York, the prime minister, Tony Blair, the leader of the opposition, William Hague, and an increasing number of others.

Even though we were running late, there was no question of putting back the launch. We had five months between finding a chair and launching the appeal. This was a great stimulus to action.

Giles on the meeting room: "This room is interesting. It is quite small, yet it is immediately behind the balcony at Buckingham Palace used for public occasions, and therefore is where all the balcony party retreat. I don’t know what they do. It must be cramped.

At the first meeting of the executive committee, the first question was how to divide the £250 million target between the volunteers. We could have spent ages discussing and negotiating, but David Svendsen, chair of Microsoft UK, suggested that it should be divided very simply: £50m from corporate support, £50m from philanthropic support, £50m from the regions, £25m each from sport and entertainment (both strongly represented amongst our supporters) and finally £50m from the public appeal. It was arbitrary. They agreed and got down to work.

It was never discussed again. Yet it was used as the basis for all sub-committee targets.

The Duke of York went to great lengths to ensure that he was fully inducted into the NSPCC, its vision of ending cruelty to children and the £250,000,000 appeal. He probed at each stage: there was no way he was going to take on a task that was doomed to fail. Having committed himself, he went into overdrive. He wanted the executive committee to be made up of the key members of the steering group that were happy to stay on, and a small number of other people who covered those areas not covered by the steering group..

Now one of the things that I hear often from staff working with an appeal board or a development committee is that “people won’t come to meetings”. The Duke of York insisted on fortnightly meetings of the executive committee. This meant that we could get the planning that was needed for the appeal organised within the period of November 1998 and March 1999, the date of the launch.

During its fortnightly meetings, the executive committee identified new people to join their committee, as well as identify the members of the full national appeal board, attempting to have representatives of all communities of potential donors.

The executive committee also agree:

- the strategy for the appeal,

- the plan for the appeal,

- the plan for the launch and

- an engagement plan for the prospects that had been identified during the feasibility study for the appeal

This gave us much of the decision making that could be taken to the national appeal board.

The first meeting of the full national appeal board was in January 1999. It continued to run the appeal until its conclusion. The chair of the appeal board, as well as of the executive committee, was the Duke of York. He was ably assisted by two deputy chairs – George Magan (who had chaired the steering group) and Lord Harris of Peckham (a long-term supporter of the NSPCC and a passionate advocate of our work).

(By the end of the appeal, the executive committee disbanded, the national appeal board had become monthly, and the number of people entitled to be members of the national appeal board increased to thirty-five, each one either chairing a sub-committee, chairing an event, or who simply had an extraordinary range of networks. Of course, they didn’t all turn up at all meetings. The process for this happening was important, but not interesting.)

Remember, the time between the Duke of York saying yes and the public launch of the campaign and appeal was just five months.

Giles paints a fascinating picture of the complexity of a campaign of such magnitude, bringing to life his memories of meetings, statements and the many obstacles he and his colleagues had to surmount just to get within five months of the appeal’s launch. Most importantly, Giles outlines the fundamental structures required before an appeal can even get to the launch phase and gives examples across of the board of the processes that led to the NSPCC’s overwhelming success. In part two we get to experience the launch itself and what came afterwards. In other words, the inside story on the appeal itself.

Part two of Giles' retrospective on the Full Stop campaign is coming on Wednesday 29th of November, and he'll be taking us into the details of the campaign including some amazing events.