Opinion: an ethical, principled approach to donors and fundraising. Part 2.

In the second part of his series of articles on how the World Land Trust does fundraising, John Burton explains which types of fundraising his organisation embarked on and which they avoided.

- Written by

- John Burton

- Added

- January 03, 2019

Editor’s note. The context behind this series:

This short series from John Burton sets out to capture in detail one CEO’s view of fundraising and how it should or shouldn’t be done. SOFII is publishing it in the belief that CEO/senior management team perspectives on fundraising are rare and of value. As such, it’s an opinion article, not a case history and it contains views that many readers might disagree with. So, please do add your comments and opinions below, as this will provide a more rounded view, encourage debate and advance understanding of the subjects and issues raised. The context behind this one individual’s critical perspective on how fundraising should or shouldn’t be done is the author’s 40+ years of voluntary sector leadership throughout which he has worked with and supported fundraisers and their teams and listened to the views of many donors. While SOFII suspects the author is being deliberately provocative in places, this experience has led John and his charity to adopt some practices and avoid others. So, SOFII welcomes constructive comment from all fundraisers, whether arguing against his views or supporting them.

Why some forms of fundraising are acceptable to WLT and others are not.

An ethical, principled approach to donors and fundraising: a strategy case study from World Land Trust.

By John A Burton, founder and CEO (from 1989-2018)

Contents

Part 1 • Why WLT exists and what it does. How we think of and treat our donors. WLT’s fundraising USP. It’s not just about money. • Appendix to Part 1: Background – John Burton’s experience and charity roles.

Part 2 (here now) • Why World Land Trust does some forms of fundraising and not others. Ethical management, board and governance. Controversial issues. Acceptable and unacceptable fundraising. Investing in what works and keeping donors.

Part 3 (scheduled for February 2019) • Trust and transparency: why it’s the most important issue of all. What happens when a World Land Trust appeal raises more money than is targeted? Plus, three blogs: 1. Criticising other charities. 2. Costs and overheads. 3. John Burton’s Guide to Evaluating a Charity.

John has worked for many high profile international environmental organisations, including Friends of the Earth (as a consultant) and Fauna and Flora International (as Chief Executive). He set up the first TRAFFIC offices of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) for The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), has been involved with the Wildlife Trade Monitoring Unit and was founding chairman of the Bat Conservation Trust.

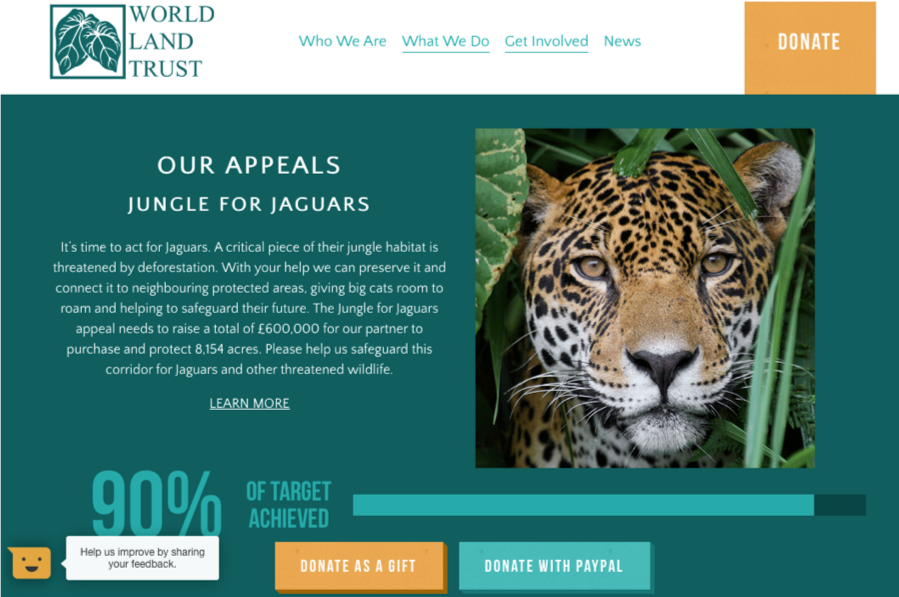

In 1989 John founded World Land Trust (WLT). Since then, having raised over £25million for purchasing and protecting land in Africa, Asia and Central and South America, WLT has saved half a million acres of threatened habitat. In 2013 John was named Natural Heritage Champion by the Charity Staff Foundation.

An ethical, principled approach to donors and fundraising: a strategy case study from World Land Trust. Part 2

By John A Burton, founder and CEO (from 1989-2018)

| In the first article in this three-part feature series John Burton described World Land Trust’s open approach to how it treats donors. From the outset the charity he founded in 1989 has tried to be as transparent and honest as they could be about how they raise funds, how they spend them and what their overheads are. This has meant that they don’t have ‘small print’ of any size. Now John goes on to describe their distinctive approach to fundraising. |

The forms of fundraising we undertake are largely based on the forms that I and most of the staff feel are acceptable. I would never, ever contemplate using any form of fundraising that I personally find objectionable. Most of our communications give an opportunity for making a donation, but we are careful to avoid ‘purple prose’ and over emotive appeals. We try to set realistic targets and when we appeal for funds for a particular project we make it as clear as possible that all funds will go to that project; we never have ‘small print’. The forms of fundraising we have utilised are as follows:

Newspaper advertising.

Thirty years ago newspaper advertising was very cost effective and we would expect around four or five times the cost of the advert to come back in donations. After the first Gulf War, this suddenly ceased to be cost effective so since then we have only used newspaper and magazine advertising when it has been free or virtually free. For this purpose we have kept a few adverts on hand for ‘distress space’ placements.

TV advertising.

We have used this a few times but the main disadvantage is that it is extremely costly, and high risk. It also requires a serious commitment for telephone support, which can also be costly. In the end we decided it was not worth the investment. And there is little evidence from other NGOs of its cost-effectiveness, other than emergency appeals. However, with the increasing number of TV Channels, and consequent fall in price of advertising it may prove cost effective in the future. Nonetheless there is a possible perception among our target audience that it is wasteful and expensive.

Internet fundraising.

WLT was one of the first charities to recognise the potential for fundraising on the internet and currently at least 90 per cent or more of our income can be directly linked to our internet presence. This is particularly important for corporate fundraising. At the time of writing WLT has never gone out and solicited corporate donors, but donors have come to us. Because of our comprehensive website, by the time a corporate donor approaches us they have invariably carried out thorough research and are already committed to us. One of our first corporate donors remained a supporter for 28 years – until they were taken over.

Internet fundraising is significantly more cost-effective than almost any other form of fundraising (except perhaps, legacies). It also has the advantage of being possible to analyse and track in greater detail than most other forms and can be integrated with SMS. However, in order to maximise the benefits of internet fundraising it has been critical to invest in suitably experienced staff and carry out website management in-house. In discussions with other organisations who have not had the same positive experiences with internet fundraising, invariably it is because much or all of their website and related expertise is outsourced. An issue that has to be recognised is that everyone has an opinion about the internet and board members often express those opinions without actually understanding not only how the internet actually works, but even failing to understand what a website is there for, and what it actually achieves. A critical feature of a website and making the internet work for a charity is re-inventing itself regularly, but also letting the experts take control.

Why we don’t do some other forms of fundraising.

As previously mentioned, one of the fundamental underlying principles behind what we will NOT do, is what I personally resent and do not like and what most other colleagues object to. If I would not donate to a form of advertising or fundraising approach, I won’t condone it in WLT. I particularly abhor any form of fundraising that is coercive. So-called ‘chugging’ – face-to-face fundraising where passers-by are stopped in the street or on their doorsteps – is a prime example of this. Not only is it highly improbable that it would be cost effective for a niche charity such as WLT, even if it could be shown to be cost effective, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence to show that in times of stress, supporters recruited in this way are the first to fall away. Similarly, I will not condone telephone calling and persuading donors to increase the amount they donate. There is anecdotal evidence that this can have serious negative impacts. This is because other charities only normally publicise success stories. When the RSPB recently embarked on a telephone campaign to ask existing supporters to increase their donations I know from first-hand experience this had some negative impacts – but quite what the overall impact was is unknown and unlikely ever to be published (it may be that it increased overall income, and if that is its only raison d’être, so be it). WLT has never been a risk-averse organisation – except for one area. We have always been averse to risking annoying our existing donors. Any form of fundraising that risks alienating even a small percentage of long-term donors needs to be considered very carefully indeed. Long-term donors are often not only the best ambassadors, but also potential legators.

Far better to invest in doing what works, better. And keeping existing donors.

Another form of advertising I do not condone is what I would describe as ‘loss leader’ recruitment. This is the type of fundraising that involves spending £10 to raise £5, on the grounds that by recruiting the donor, over the lifetime of the donor, it will produce far more than £10. While this may or may not be true – and proving it or disproving in the short term it is difficult -- I believe it to be immoral at best and illegal at worst. This is because the donor probably believes their £10 is going to a very specific good cause. They really do believe their £10 will save a starving child, or go to helping bears. And the reality is that not only is not enough raised for that donor’s £10 to go to the cause when the costs of the advertising campaign is met, plus the cost of handling the donation, but their future donations will probably go into unrestricted funds, to cover some of the organisation’s overheads. So, charities should only invest in fundraising when they have the money to do it, obtained from some source that’s quite clear how their funds are to be used. Telling donors that they are helping a child when they are simply funding the charity’s growth strikes me as misleading and immoral. And even using a legacy when the legator thought that the money was going to fund the objects of the charity is something I would not condone.

WLT does not give away ‘free gifts’ particularly cuddly toys. In the past we have investigated the cost effectiveness and were even given some as gifts, but decided this was not right for our image. We have given away donated bars of fair trade organic chocolate, as part of a specific campaign – but this has been at no cost to WLT. And we have had prizes for competitions, but again at no cost to WLT. The only thing a donor normally gets in return for a donation is a newsletter informing them about the results of WLT’s conservation work, a leaflet about a specific project and a paper certificate recording their donation. All the feedback we have ever had suggests that this is what our donors want. There is of course an argument that we could increase our supporters by using other methods, but I have always believed this risks alienating our existing loyal supporters. It is better to have a relatively small but committed donor base, than a large group responding to more trivial advertising.

Ethical investment policy.

Ever since WLT had funds available for investment, it has ensured that these are invested in an environmentally sustainable manner. As such it does not have an ethical policy because it is essentially subsumed into our environmental policy. However, we have always viewed such policies as being very important and this together with a background of experience in the area has led to WLT being asked to manage funds in excess of $1 million on behalf of partner organisations.

Controversial issues

Arguably part of WLT’s USP is that we have not shied away from controversial issues. In fact, we had meetings at the Royal Society rooms in London deliberately entitled ‘Controversial Conservation,’ led by eminent environmentalist and broadcaster, Chris Packham. By ensuring we have a first-class network of partner organisations with high standards of scientific research, together with our own network of some of the top conservationists we are able to not only have outspoken opinions, but also to back them up with facts. This generally resonates with our core supporters and all the evidence is that it encourages support. A good example was when I wrote articles, blogs etc. criticising several charities (including Oxfam and Christian Aid) over ‘selling’ goats as Christmas presents. Apart from some charities criticising me for criticising them we had nothing but a positive response and it also encouraged new donors. I have an extensive file documenting issues concerning goats, wildlife and degradation of the natural environment and subsequent correspondence from other charities. See appendix 3. And despite being openly critical of other charities it only appears to have positive impacts, as far as our supporters are concerned.

Over the past several years I have also been a regular contributor to Third Sector magazine on issues relating to the ethics of fund raising, taking a critical stance in line with some of the views expressed in the documents listed in appendix 3. This lists some of my blogs on issues that might be considered controversial, none of which appear to have damaged our reputation. In fact, some of them reflect opinions stated by others such as our Patrons.

Ethical management, board and governance.

WLT has grown its board over the years (initially only three Trustees, now 10 Trustees plus an advisory Council). The expertise of the Board has been reviewed regularly to ensure that there is a representative range of skills both to carry out the fiduciary duties of the Trust, but also to provide relevant advice to the executive. A guiding principle throughout the Trust’s history has been that all trustees and council members should be known to the trustees and chief executive prior to appointment or election. This has led to meetings being generally (but not always) harmonious and productive. Boards can be very helpful, but they can also be very unhelpful. Over the years I have experienced both. A common problem involves Northcote Parkinson’s ‘Bicycle Shed Theory’. A huge amount of time can be spent on trivia, simply because all board members know a little bit about it, and all have an opinion. Worse, is when board members think they know about topics such as fundraising an think they have original ideas. The reality is that they rarely know anything like as much as the staff actually doing it, but have to be listened to because they are on the board. Another problem that requires very careful management and has been dealt with in many other publications, is managing the board and managing the chairman. In very small charities a chairman is often also de facto the chief executive (albeit voluntary). But even in larger charities the chairman can also try to take on this role. And managing this can be not only difficult, but hugely time wasting.

‘Ideas are ten a penny, but you need many pounds to make the idea work’

This is an adage, I don’t know from whence it came – it may even be original to me. But frequently board members come up with ideas which are not only usually very unoriginal but also very difficult to implement. My experience has consistently been to try and explain to anyone what the problem is: that basically any bright idea must have a means of implementation, of delivery accompanying it and the organisation must have the resources available to deal with it. And finally, it must not distract staff from existing work, unless it can be clearly demonstrated that the benefits are considerably greater than their existing commitments. New ideas have never been a problem with World Land Trust. Over the years I have seen enough wheels re-invented to run an intercity train, but rarely seen the rails on which to run that train.

The cost of fundraising

The cost of fundraising is always higher than donors like. Different forms of fundraising have differing levels of cost, and differing types of charities and causes get widely varying rates of return – it’s easier to raise funds for sick donkeys than for schizophrenics. And despite what a lot of the public think, raising money for wildlife, particularly overseas is often difficult. Plus, it is definitely subject to fashion: Gorillas and Orang-utans are much easier to raise money for than bats and shrews. But years ago, animals such as whales were unpopular and seen as a source of cheap food. So, attitudes can be changed. Until the 1980s, when the Bat Conservation Trust was formed, bats had a generally poor public image, but over the past three decades, that has changed significantly. Consequently, it is usually essential, in order to engage public interest to use the ‘charismatic’ species to front fundraising campaigns. It is critical to manage how and when money is spent on fundraising. While we have no hard data to support this assertion, I believe that donors who decide to support WLT, on the whole are less influenced by charismatic species, such as snow leopards and rhinos and elephants, than the general public. That is not to say they don’t first come to WLT because of our use of the images of charismatic species, but those who become significant long-term donors are probably more concerned about wildlife in general.

When considering where to spend money few charities really look closely at their own finances. Ken Burnett has pointed out that keeping money in a bank, or investing it in the stock and bond markets and taking investment income, is rarely a good option when compared with the return charities can get from prudent investment in fundraising. WLT only invests the minimum need to maintain solvency, or in some cases because the money was given as a restricted endowment. As Burnett has pointed out, unrestricted money is always best invested in fundraising of some form or other – or simply doing more of what the charity was established for.

However, this creates presentational problems in a charity’s accounts, as donors do not like to see high spend on fundraising, even if it is actually producing a better yield that investing in bank savings, stocks or shares. One way of overcoming this is for fundraising costs to be netted off before income is declared, but this then risks being ‘discovered’ and criticised. So it should be done, but only openly and transparently.

The issue is not simple however; many charities do invest in recruitment of new donors, and do not expect to cover the cost of recruitment in the first year or two. In appendix 2 I have described an actual scenario, to which I personally have a very strong antipathy. And I believe that WLT’s policy of ensuring that every donation made by a supporter goes to the project they expect to be supporting is an important principle. WLT has made it clear that it does take a management charge out of most donations, as clearly funds are needed to run the charity. But it has been possible to operate on an overhead of under 18 per cent of income. Putting it crudely (and not entirely truthfully), 82 per cent is spent of conservation. However, this is not how the majority of charities operate and I have blogged and written about this issue.

Investment in fundraising.

According to Ken Burnett, ‘Charities would be much more effective and more successful if they invested sufficiently in fundraising. More voluntary sector initiatives fail because of underinvestment than from spending unwisely or too much.’ While I broadly agree with this, as usual the devil is in the detail. It’s where you draw the line. And in my view the lines drawn will always be dependent on the type of charity, and the type of donor the charity is trying to attract, as well as the overarching ethos of the charity itself. At WLT we created a profile of being a very low overhead charity. The Trustees decided that no more than 15 per cent should be spent on overheads, although this was later amended to 18 per cent. This was extremely difficult to achieve without resorting to the type of accounting where a large proportion of overheads are labelled as ‘outreach’ or ‘education’. We always tried to be as honest as possible and it made life very difficult. In the early days it was achieved by underpaying staff (particularly the senior staff, including myself). There was a transition period when staff were increased and I started to take a more realistic salary. During this transition it was extremely difficult to maintain the low overheads. However, once the income started to grow, and larger donations came it became increasingly easy to maintain a low overhead, while still investing in fundraising. But a glance at other relevant charities’ accounts suggest that it is not uncommon to spend about 25 per cent of income on overheads and fundraising, and it can even be more than 40 per cent. But unravelling the true figures and making them comparable across the charity sector is impossible. Internally, within WLT we have often referred to some of our donors, particularly from the corporate sector, as WWF refugees. This is because they have considered supporting WWF, but having researched or contacted them, decided that WLT was more appropriate. The reasons are very variable, but the transparency of WLT accounts is usually cited as one.

The cost of fundraising should be seen as an investment, not as a cost. As overall guidance, I believe that any investment in fundraising should never be a net drain and always produce a profit. Of course, this is not always possible and there are occasions when ‘profile raising’ is also important. Legacy fundraising is a prime example of this, since on average, people do not die until something like four years after they have written their will. But Ken Burnett’s argument is to an extent based on the premise that many charities have significant investments, rarely producing more than 10 per cent per annum; more likely three or four per cent. That same money invested in fundraising could produce far more; perhaps as much as 30 per cent or even more. It is a sound and a strong argument for not sitting on huge reserves, one that were WLT to have ever had significant unrestricted reserves, I feel it is a course of action I would have undertaken. Unfortunately, the reserves held by WLT were nearly all restricted and the largest (over $1 million) had strict rules about how it could and could not be invested.

As founder of WLT I have been in a unique position in defining what is an acceptable type of fundraising. As stated previously, I have based the decision on what I and most of my peer group find acceptable. Obviously, first and foremost it needs to be legal, decent, honest and truthful. I certainly believe this is not the case for many charities. It also should be open and transparent and allow donors some considerable degree of control of how they are approached, what about and when. A charity should not pester, pressurise or even persuade, because giving has to be a voluntary act, freely given and respected. Because charities want to keep donors it also has to be a pleasant and rewarding experience, worth doing again. That is how I judge a charity and how I expect to treat donors. Any charity that engages in ‘chugging’ gets dropped instantly if I am aware (a former supporter of Amnesty, I stopped as soon as they approached me in the street). Any charity that phones me unsolicited, I drop (I cancelled by subscription to the RSPB when they phoned my wife). I empty the contents of magazines into the recycling and rarely if ever read them. I do read adverts in a magazine (don’t ask what is the difference between that and an insert in the same magazine – probably just idiosyncratic bloody mindedness). But I will drop small change into a charity box by a shop or café till. These are all personal attitudes and a professional fundraiser will argue that it doesn’t matter, because overall the methods I criticise do raise money. I simply don’t care. I want donors to the WLT to come, because they feel they are joining a nice organisation. That they are not joining simply to be squeezed for money. But that they are joining us because they believe in what we are doing and how we are doing it. I also believe that by treating donors with this high level of respect they are likely to be as generous as they can afford and may well even decide to leave a legacy. The problem is that professional fundraisers are under pressure to produce results: to hit targets. To me, the target should not be measured simply in numbers, numbers of recruits, amount raised. But in terms of donor engagement, donor satisfaction, I believe in the long-term. And the proof of this particular pudding, is that WLT is beginning to receive legacies. I predict that within a few years these will average over £1million a year.

To quote my fundraising guru Ken yet again, ‘Fundraisers need to put the donor experience to the fore, not their financial targets. If they trust their donors and provide a good experience the money will come. It always does.’ It takes some stamina to believe this, but I do believe WLT has proved it.

In Ken’s words WLT ‘moved from a marketing and acquisition mindset to a service and respect mindset. And treated people as we would wish our mums and dads to be treated, or we’d wish to be treated ourselves.’ And Ken concluded that ‘...if charities applied that rigorously, bad fundraising just wouldn’t be possible.’

Coming next on SOFII

Why World Land Trust believes trust and transparency is the most important consideration of all.

In this the third and final part of his feature on an ethical, principled approach to donors and fundraising from a CEO’s viewpoint, John Burton considers the importance of trust and transparency for World Land Trust and its supporters and concludes that few things matter more than a commitment to ‘doing the right thing’.

© John Burton SOFII 2019