CDE project 6 section 4.8: Craig Linton and Paul Stein on emotion

- Written by

- Craig Linton

- Added

- May 03, 2018

Craig Linton and Paul Stein on emotion

by Craig Linton and Paul Stein, from their book Donors for Life

Donors for Life is a new book written by two seasoned fundraising leaders, Craig Linton and Paul Stein, who recently got together to produce the definitive guide to relationship fundraising from the practitioner’s point of view. There are lots of good insights in this packed tome about emotion and how to use it effectively. Here are just a few short extracts, to give you a taste.

From Chapter 1: how this book came about.

Fundraising lacks emotion

To paraphrase David Ogilvy: you cannot bore people into giving to your cause. Yet sadly we see too many charities trying to do this through inaccessible language, poor images and vague asks.

Giving is a personal and emotional decision, yet we try to rely too much on logic and rationality to make our cases.

Many larger organisations have copied some of the worst and most annoying practices of the commercial world, such as automated call centres and outsourced response handling. This has removed the core human-to-human interaction and connection that are essential to feelings of altruism and giving. When you believe you’re a number in a machine and your donation isn’t making a difference, then of course you’ll think twice about giving.

To revolutionise our fundraising in the coming years, we need to reconnect with our donors emotionally and make them feel a valued and important part of our mission to change the world.

From Chapter 4: why people give and the importance of emotion

A classic process for successful relationship fundraising:

- Make the donor feel at home, welcome and needed (relationship building).

- Lead with a strong emotional story/experience (storytelling, the why).

- Back up the emotional case with rational reasoning that demonstrates the need (the why).

- Involve the donors and show them how they can help (relationship building, asking properly).

- Make a specific, tangible and non-aggressive ask (asking properly).

- Thank, report back and make the donor feel good about giving (data collection, donor magic).

- Repeat.

How can you put this into practice and make sure emotions are at the core of your fundraising?

In Emotionomics, Dan Hill argues there are six key emotions that drive an action, such as writing a cheque or signing a petition. These key emotions are:

- Anger

- Disgust

- Fear

- Happiness

- Sadness

- Surprise

It’s easy to see how the six primary emotions apply to relationship fundraising:

- Anger: how could someone abuse a vulnerable child? It makes me furious.

- Disgust: how can some parents allow their daughters to be cut by a tradition such as female genital mutilation? It disgusts me that society turns a blind eye.

- Fear: global warming, deforestation, animal extinction. What sort of world are we leaving for our grandchildren?

- Happiness: after slowly nursing Rover back to health, it was a joy to see him running round the field with his tail wagging and tongue lolling.

- Sadness: a tear rolled down the nurse’s face. There was nothing more she could do. The child was going to die.

- Surprise: wow! It only costs £10 to solve the problem? Who’d have thought it could be such a bargain?

Each of these primary emotions has a scale of intensities. Happiness ranges from satisfaction to joy, and anger goes from mild annoyance to rage. At its most basic level fundraising is simply a case of triggering a negative emotion and then offering donors a solution that provokes a positive emotion. Need, then reward.

Managing the emotional content of your fundraising is an important task. For example, if you go too high on the disgust, then you may turn donors off before you get to the solution and offer.

GUILT AND NEGATIVE EMOTIONS – A CAREFUL BALANCE FOR RELATIONSHIP FUNDRAISERS

Guilt is a very powerful emotion and can be extremely effective. However, we believe it is a dangerous emotion for the relationship fundraiser so should only be used with great care. It is negative and you need to avoid exploiting this emotion in unethical ways.

The Institute of Fundraising Code of Practice in the UK now outlaws the practice of sending money or unwanted gifts, such as tea towels, in direct mail packs that rely on reciprocation and guilt to get people to donate. The relationship fundraiser should avoid them (we will look at what makes a good incentive and involvement device in chapter 8. In general, we think the banning of such ‘phoney’ gifts is a good thing.

Fundraisers need to be careful not to confuse guilt with a sense of injustice or feeling over-advantaged compared to others (i.e. my children are much better off than children in poor countries). Charities have a duty to report on the problems of the world. We shouldn’t try to sanitise the reality of the work we do. If pictures of starving children, tortured animals and devastating disasters are genuine, or representative of the truth, then we shouldn’t shy away from using them.

The fact that these images provoke strong negative emotions isn’t a bad thing. In fact, it is almost essential. Giving is a simple way that people can channel that negative emotion and so experience all the joys of giving that we talked about earlier.

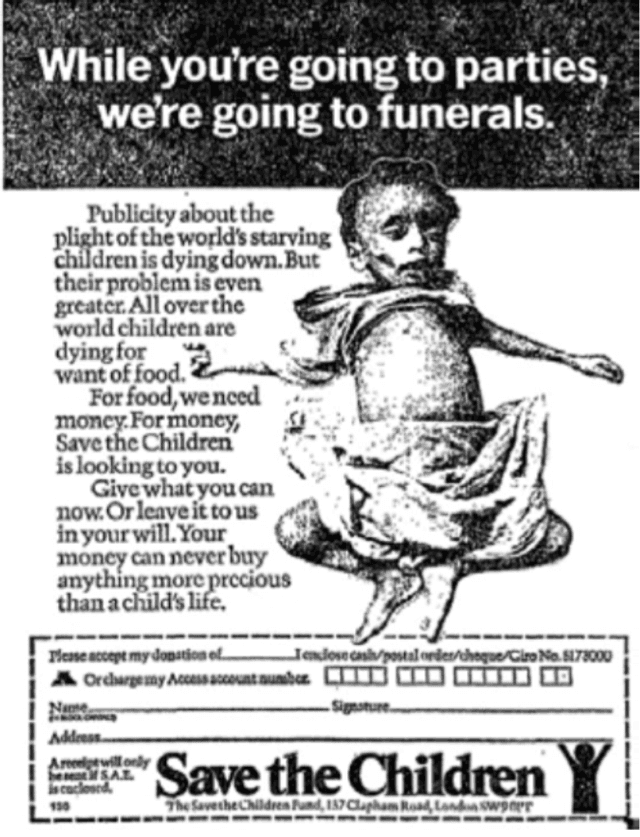

There can be a fine line between highlighting a specific problem that provokes a strong negative emotion (disgust, sadness, fear) and overtly using guilt to make donors feel the problems are their own fault, thereby guilt tripping them into giving. There is no easy way to decide when that line is crossed. Every person will have their own tipping point when something goes too far. Adverts like this one from Save the Children in the 1970s wouldn’t be socially acceptable now as we believe it relies too much on guilt to provoke a response.

Compare this approach to the emotional power of SCF’s current No Child Born to Die campaign, below.

This took the long over-rationalised case to reduce poverty and made it a hyper-emotional imperative.

Ultimately, the best relationship fundraisers will be those who understand the power of emotion and use it sensibly, wisely and carefully in their fundraising. We need to recognise the sense of injustice, fear and sadness and combine it with more positive emotions, such as hope, joy, achievement and happiness to take donors on a journey where, ultimately, they feel good about giving and the difference they are making.

THE IMPORTANCE OF IMAGERY

The phrase ‘a picture paints a thousand words’ is a cliché, but, as explained earlier, we now know it is also neurologically true. Getting the right imagery in your fundraising can make the difference between success and failure.

We have a section on choosing the right imagery in your fundraising in chapter 8, but we wanted to explain the biology of why imagery is so important here.

Dan Hill, author of Emotionomics, gives us the answer:

'A battle between pictures and words is like one between Mike Tyson and Tiny Tim: the picture throws the bigger punch.

Consider the following:

Two thirds of all stimuli reaching the brain are visual. Over 50 per cent of the brain is devoted to processing visual images. Eighty per cent of learning is visually based. Business people, take note. Humans are extremely visual: we think largely in images, not words.'

He continues:

'For anyone who wants to ‘get back to basics’, remember that nothing is more basic than non-verbal communication. Human beings have existed for over 500,000 years, but we’ve had the benefit of language for less than a quarter of that time.

Moreover, because the rational and sensory parts of the brain aren’t adjacent neighbours, we’re not very good at verbally describing the details our senses detect. Ironically, that’s true despite the fact that our gut-level perceptions are largely based on sensory impressions.'

All of this means that if we want to elicit emotion and response in our donors, then understanding the imagery that supports and underpins our fundraising message is crucial.

In practical terms, think of the last time you cried or got emotional.

Take a second to recall the experience. What springs to mind? Do you paint a mental image or do you remember the words that were written or spoken? Having asked hundreds of people this question, we’re willing to bet it is an image that comes to mind first.

MEASURING EMOTIONS IN YOUR FUNDRAISING

How do you know if your appeal or campaign has enough emotion in it? How can you measure emotion?

Most research methods, such as focus groups or online panels (we’ll look at research methods in chapter 19) are based in rational thought. They give people time to think and respond in a thought-through way. Yet, as we’ve demonstrated earlier, it is the instant, emotional response that we need to measure.

The simple fact is that there is no easy, cheap way to measure the types and strength of emotion in your fundraising. In fact, measuring emotion is an emerging scientific field and is currently prohibitively expensive for all but the largest charities, and maybe even for them too.

There are currently two ways to measure real time emotion and reactions. Both use complicated science and advanced technology to measure minute changes in your body. These include temperature, sweat, heartbeat, micro- spasms and eye movement.

The first involves selecting suitably willing and representative candidates who match your donor profile, then attaching super sensitive sensors that t to their skin so you can measure micro-changes in their skin temperature and conductance. These have been used in medicine to help understand the emotional reactions of non-communicative autistic children to various stimuli.

The second is through using facial coding technology to record a person’s facial expressions. This records micro-changes in the facial muscles (human beings have more facial muscles than any other species on the planet) to map out the type and intensity of emotions you are feeling in real time.

Not convinced? Take a second to think of the face of someone who is very happy. What characteristics does it have? Contrast this with the face of someone who is extremely angry. You’d know instinctively which person is which.

Alternatively, think of a time you have laughed politely at a joke versus when you have been crying with laughter. Again, the difference in facial expressions is something you would identify instantly.

The business world is beginning to catch on to the importance of testing for emotion in advertising. For example, Forbes magazine got people to watch commercials online and measured their happiness via their facial expressions on webcams. The one that made most people smile was Volkswagen’s ‘ The Force’ commercial, which parodied Star Wars and is worth watching if you have a couple of minutes to spare.

We predict that in the next five to 10 years the costs of the technology will tumble, so it will be accessible to every relationship fundraiser, not just big companies. It will become the norm to test for the emotional response of appeals before launching them. is should, in theory, revolutionise fundraising and reduce the number of dull, emotion-free fundraising failures that currently exist.

CONCLUSION

Fundraising is full of truisms and basic principles that have been passed from generation to generation of fundraisers. One of the most quoted is (usually attributed to Harold Sumption):

'Open hearts, open minds, open wallets.'

We’ve heard this in many conferences and read it (in various guises) in numerous books over the years. The best fundraisers instinctively know this is true and understand how important emotions are in soliciting gifts.

As we have shown, we now have the scientific knowledge to prove what previous generations instinctively knew was correct. Giving is good for us and is an emotionally led decision.

Fundraisers can develop and execute the most sophisticated and brilliant campaign in the world. In fact, we’ll try and show you how to do this later in the book. However, even the best-planned appeals will fail if they lack emotion and don’t connect in a way that makes potential donors want to give. That’s why we’ve dedicated a chapter of the book to emotion and motivations for giving.

Quite simply, they underpin every aspect of fundraising and need to be understood by every fundraiser who wants to change the world.

From Chapter 9: the seven elements in action. Five outstanding campaigns.

The Oxfam street fundraising campaign

Editor’s note: Before leaving Donors for Life I just wanted to bring in one great example that Craig and Paul share, because it’s about emotional storytelling on the street. One to one fundraising face to face on the street is a big area for fundraisers. It’s a challenge because the donor experience and public perception of it has to improve if it’s to survive. Here Oxfam shows a positive engagement initiative that will lead to opportunities to tell their emotional stories in ways that should have wide appeal.

Response mechanism An instant text from your mobile.

Emotion and story Oxfam had developed a bucket with a tap for use in emergency situations around the world. The bucket has a lid to keep out dirt and a tap to stop contamination. This gave the street fundraisers a great story to tell to prospective donors.

Pictures and layout Although this was a street fundraising campaign, the supporting materials and bucket design were all easy to read and explained the offer clearly.

Offer and involvement Donors were cleverly offered three options to give. You could give £2 to fill the bucket, £3 to pay for a bucket, or £5 to buy it and fill it. Donors who sent a text were then followed up with a phone call to ask them to take out a regular gift.

The bucket is a great conversation starter, offering a tangible image of what the donor’s money might buy. Using this involvement device sparked the potential donor’s interest, as he or she invariably wanted to know more.

Narrative and copy The street fundraisers were trained to tell the story of the bucket in an engaging and emotional way. Similarly, the follow-up calls used a powerful story to ask for a regular gift.

Data The data from the SMS messages were then used to call people back and ask them for a regular gift. The phone call also asked for the donor’s name and address, so even those who didn’t sign up for a regular gift could still be kept informed.

Results The campaign was developed in conjunction with fundraising agency Open Fundraising. During an e-mail conversation, Paul de Gregorio, head of mobile at Open, shared his thoughts on the campaign with Craig:

‘I love this campaign because it provided a way for the potential donor to really see what their money could do. It created a genuine moment of engagement between fundraiser and donor on the street, something that could then be referred to in the follow-up phone call. We called it ’street theatre’ and its introduction in this campaign resulted in average SMS donations that were higher than we’d previously seen.’

Donors for Life: a practitioners guide to relationship fundraising by Craig Linton and Paul Stein contains much more detailed content on how fundraisers can successfully use emotion and lots more besides. For more about the book please see here, https://goo.gl/TtEOi2.