Legacies, they’re nowt to do with thee!*

In an extension of his talk at IWITOT 2018, Ashley Rowthorn explains how developments in neuroscience can help run a great legacy campaign. *Roughly translated from the Yorkshire dialect, the headline means ‘Legacies are not really about you!’

- Written by

- Ashley Rowthorn

- Added

- May 09, 2018

Introduction

When it comes to looking for fundraising inspiration, we tend to get excited by pieces of creative brilliance, or wonderful emotional storytelling. And rightly we should. But when asked to present at this year’s IWITOT conference in London on the subject of legacy giving, I knew instantly what I needed to share. That was the experimental psychology and neuro-imaging research carried out by Professor Russell James at Texas Tech University in the USA. This ongoing piece of research is transforming our understanding of why donors leave gifts of legacies in their wills, giving nonprofits around the world the insight to have powerful conversations that could unlock billions in legacies.

To do this, Russell James decided quite literally to go inside the mind of the donor.

The problem

It all started with a problem: that legacy or bequest giving behaviour does not seem to follow lifetime-giving behaviour. Russell observed that while an estimated 70-80 per cent of Americans engage in charitable giving each year (Giving USA Foundation 2011), less than 10 per cent have a plan for their giving after their death. The same figures echo in other parts of the world — such as the UK where only 6-7 per cent of people are dying with a charitable gift in their will. And this is despite around one third of donors saying they would consider such a gift.

So while the act of philanthropy is well-established and the intention to leave a legacy is very present something appears to be going wrong that is preventing people from leaving legacy gifts. This behavioural gap suggests that there is a fundamentally different decision-making process involved in lifetime giving versus legacy giving. And if we do not find out and fix this problem with more effective legacy fundraising then as Russel points out ‘90 per cent of donor mortality will only result in lost current giving’.

Methodology

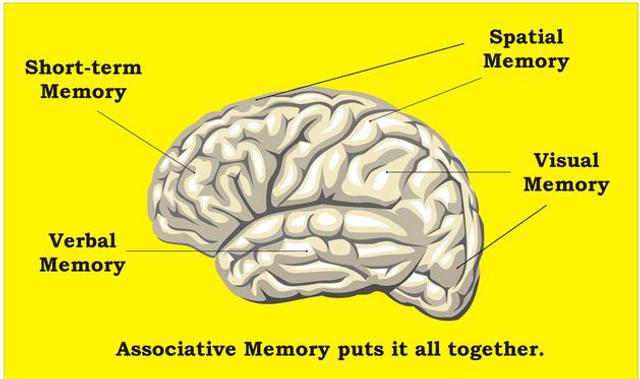

This ground-breaking study was the first to examine legacy and bequest decision making using fMRI techniques: scanning for brain activity to find out what happens in the mind of donors when contemplating different ways of giving.

Participants in the study participants were placed in a fMRI scanner and asked to answer questions on their likelihood to donate, volunteer, or write a bequest in a will in the next three months and presented with a range of charitable organisations to consider.

The fMRI scanner looked for statistically significant differences in brain activity when the participants considered lifetime giving versus bequest giving. And the results showed that contemplating legacy giving decisions uses a fundamentally different part of our brains.

The results

When thinking about legacy giving, two areas of our brain light up — the precuneus and lingual gyrus. These are both found at the back of our brain and form part of our visual memory system. The precuneus is often known as the ‘mind’s eye’ and is used when taking a third-person perspective on oneself. The lingual gyrus is critical in giving us the ability to dream.

Other studies have found the same areas of the brain activating when looking back and recollecting on life events and family photos of significant memories.

Russell hypothesises that legacy giving is essentially a ‘visualised autobiography’ — a reflection on our life, our loves and our values; in choosing the people and nonprofits we want to pass our inheritance to we essentially write the final chapter in our life story.

A legacy gift becomes a legacy dream. A way for donors to live in some symbolic way and continue to do good beyond their lifetime. Ultimately, for them, to find answers to some of the biggest problems that eluded them in life: the cure for cancer, the eternal memory of a loved one, the protection of a special place.

Stories

As fundraising and leadership coach Stephen George in the UK has said many times: ‘Stories are the currency of legacy giving’.

And while the gift itself is the final part of the donor’s story, we see that storytelling, especially telling stories of other donors that are leaving legacy gifts, has a significant influence in growing legacy giving.

In a follow-on study, Russell James and Claire Routley tested the influence of donor stories in encouraging people to include a charitable gift in their will. They found that the more stories we tell, and the more the story reflects the life story of the reader, the more likely people are to consider a legacy gift themselves.

Conclusion

This research highlights three fundamentally important principles that we need to consider when engaging in legacy or bequest fundraising:

- Donors approach legacy giving in a completely different way to lifetime giving.

- We only see donors leaving legacy and bequest gifts to organisations where there has been a clear and important connection to the cause in their lifetime.

- The best form of fundraising is in telling stories that closely reflect the donor.

So what does this tell us?

Primarily this research shows us that legacy giving is all about the donor and has nothing to do with our organisations. Legacy giving is indeed the most donor- centred fundraising of all.

To become great legacy fundraisers, we need our legacy- fundraising approach to be radically different from that of our lifetime giving programmes and we have to show how our organisations matter personally to our donors.

To become great legacy fundraisers, we have to become truly donor-centric and the starting point is to better understand our donors. Put them at the start and the heart of our legacy-fundraising strategy and the rest will follow.

There is significant potential indeed to grow long-term, sustainable income streams from legacies and bequests. Perhaps an unprecedented opportunity. But to do this we need to heed Russell’s warning and become better fundraisers. Brilliant perhaps.

Not just to raise more money, but to help our donors die fulfilled, aligning their values with their assets. That is the true place of legacy.