Meet the world-changers — mindful fundraising: an interview with Karen Bolton of Mind

Karen Bolton of Mind takes us through her career, why working for Mind matters so much to her, how their workplace encourages employees’ wellbeing and how she’s changing the world.

- Written by

- Joe Burnett

- Added

- August 02, 2018

‘Six years ago it would have been inconceivable for us to go into a school to talk about mental health. The teachers would have run a mile. Now they’re the ones contacting us.’

Karen Bolton

Objectives of the meet the world-changers series:

- To encourage employers to talk about the good that they do at least as much as about the money they make. To elevate the status of service and ideals at work.

- To enable people, particularly young people, to see that they too can make a social difference at work.

- To inspire people to actively encourage their employers to add those dimensions that make a difference, that lead to practical social change.

- To raise the status and potential of jobs, or rather careers, that change the world.

- To showcase innovative ideas for fostering social change initiatives and define ways to reward employers who encourage social innovation and activism.

- To create and present a series of inspirational case histories (at least monthly) of role models who have and are making a difference, day in and day out, through the work that they do.

- To explore the emotional side of work: the taboos and the inhibitions.

Mindful fundraising: an interview with Karen Bolton of Mind

Karen Bolton is head of community & events fundraising marketing & innovation at UK mental health charity Mind. She is the strategic lead of a team of 20 community and events managers, officers and coordinators raising over six million pounds per annum from a mixed portfolio of community and events fundraising activities and events.

What is your background and how did you become involved in fundraising?

I did a psychology degree when I was 18 and I really loved that, the humanities and the neuroscience around [psychology] and after my studies I realised I didn’t really know anything about life [laughs] so decided I would work with people for a year, which became seven years, in the social care sector. It was very direct frontline work particularly with people in need of palliative care and people with motor neurone disease. I then evolved and did more sort of office work and training.

At the time I worked for quite a small charity and there wasn’t much room for progression. Alongside that I started fundraising for a children’s hospice and thought ‘I could do this for a living’. I really loved it and got a job as a fundraisers for an adults’ hospice and progressed to community fundraiser and events fundraiser. I've worked for four charities and I found my space when, with Mind, I began working for an organisation where I felt a connection to the cause. The social justice and social care aspects of palliative care and mental health are really important to me and I’ve now been at Mind for six years. I’m also a trained person-centred counsellor so it feels that fundraising is my profession, my skills set, but actually the mental health aspect is what’s really important underneath that.

In your experience, do young people coming into fundraising do so with an ambition to change the world?

This is an interesting question. I think it depends on what kind of world of work they’re going into. I suppose that, particularly for Mind and for people working in community and events, people are there because they have some sort of connection to the cause, or some sort of desire to do something that’s good as opposed to because they’re looking for skills or a career. We do tend to get ‘change- the-world’ types, but especially people wanting to change the mental health world. So we have a very high proportion across the organisation of staff who declare their own mental health condition and pretty much everyone will have some sort of connection to mental health. That might not be true for a lot of other charities.

How they want to change the world is a little harder to define [laughs] and speaking from a community and events fundraising perspective, it’s hard, particularly coming in at entry level as you’re probably stationed on points for eight or nine hours, you’re lugging boxes, stuffing envelopes and so on. It can be a slog so you have to want to do it. Feeling that you’re part of some change can be a motivator.

Has the professionalisation of fundraising changed things?

I think it has. In some ways it has changed the expectation of where you go next. It’s made fundraising more structured. When I first joined the hospice I didn’t know what community fundraising was. A lot was down to chance. When you work for bigger charities in particular you have a clear idea of where what you’re doing will lead and why. It feels a lot more linear, which I don’t always think is for the best. I learned most from the areas I didn’t know I would be working in or didn't think I was interested in. There’s a lot of organic learning.

Have you had experiences of working with charities, Mind or others, that do things differently to the norm and were these successful?

Mind is different and it comes back to the earlier point that people working here will often have that self-disclosed mental health problem. The percentage is probably the same as any other work place but that self-disclosure and openness is very different here. Apart from the fact it’s what we do, it can have a huge benefit because it attracts people who feel they can be their whole self and we have really strong workplace wellbeing structures, such as wellness action. It’s a norm, not just for mental health but overall wellness, and we have reasonable adjustments to employees' work. For example, if you experience anxiety and getting on the tube to be here at nine o’clock is damaging to you then you can start at ten. It’s an ethos the whole organisation ties into. I find it a more honest way to work.

Mind also has something called reflective practice, which was initiated relatively recently after staff said they needed a space to debrief, particularly given they have a strong connection to the cause, if they’ve, for example, been on the phone to someone in distress. That can have a strong impact on someone who themselves might have mental health problems. So we have a counsellor who comes in twice a month and does individual sessions for people to discuss work-related issues. We’re not perfect and I always say we should be best practice, but it’s more open than other places I’ve worked. I love being a manager [here] because I learn so much about my colleagues.

Do you think this is something that could happen in all or most organisations moving forwards?

This is an interesting question. I think the move is there but is it a genuine care for staff to be well at work or is it more just an attempt to keep people going and being productive? I’m always a little bit wary. It comes back to whatever the ethos of the company is. It’s more complex than just doing a bit of mindfulness – awareness of yourself and the world around you – and it can’t be used to cover up workplace issues such as heavy workloads or poor systems. Some companies we’ve worked with, such as Deloitte, have come a long way. Others are still miles off.

We often hear or read that young people feel powerless in the modern world. Do you think this is a reality, or can they feel empowered in their careers? How so?

I think it is and isn’t a reality. I’ve been thinking about the idea of social mobility that gets thrown around a lot. There’s hardly any social mobility in this country: where you go to primary school probably dictates where you go to secondary school, college and university and the job you get. The power structures are quite strong in this country so if you’re part of them it’s brilliant and if you’re not, no wonder you fear. There’s still a sense that as you try to get into the workplace it’s not what you know but who you know. When we bring volunteers into the office they tend to be of a certain age, a certain ethnicity and a certain socio-economic demographic because who can afford to work for free for three months in London? You start to narrow the field for people so I can see that young people feel powerless if the doors are closed before they even get started.

But I sort of flip that around and there are opportunities because of the way the world is changing with social media and the ability to network with people online and on a global scale. There seem to be more entrepreneurial opportunities for young people, so they don’t have to go to the bank and sign up to a 25-year loan or something when they can crowdfund. You do have to have a certain mind-set and motivation, though, that not everyone has. But also there are more opportunities, in our political climate, for young people, as in the USA over gun control, to say ‘Listen to me, I have this social cause and a platform to promote it. So I’m not going to be quiet’. It’s a mixed picture, with a lot of nuance.

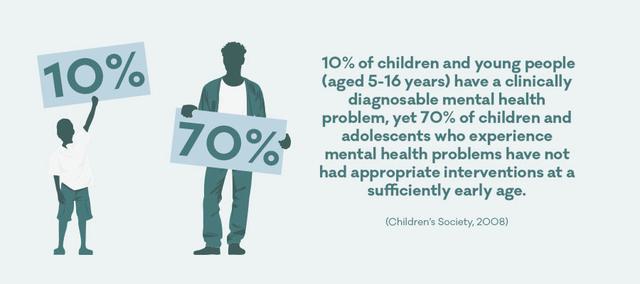

Mental health is interesting because we see the age of people identifying with having mental health issues reducing but they also want to do something with mental health. I’ve been at Mind for six years and student fundraising was there when I started but not much, whereas it’s really big for us now because mental health support on campuses is so poor people are starting to organise and set up groups. We’re even seeing it at younger ages, we’re talking schoolchildren. Six years ago it would have been inconceivable for us to go into a school to talk about mental health. The teachers would have run a mile. Now they’re the ones contacting us. So there is powerlessness but there’s also a regaining of power albeit sporadically.

What are the barriers that people feel prevent them from changing the world?

Sometimes it can be a case of not knowing where to start. There are so many causes and they’re all so important with so much change needed that we can end up in almost a state of paralysis. But sometimes just standing up and saying ‘this isn’t good enough’ can be a change itself. Just raising consciousness is worthwhile.

Who are your role models in the fundraising world?

Not so much role models but certain causes have inspired me. Some charities have such a good brand sense and voice. Anthony Nolan [a UK-based cancer charity] is one I have to bring up because their fundraising voice is just on the money, it totally embraces what they exist for. That slightly irreverent tone and that ability to connect really feels like it’s personable. As someone who doesn’t have any experience of bone marrow I still support them because what they do makes me feel so connected to the cause.

In terms of role models for me, they’re just people I come into contact with who are roughly at my level. There’s so much shared learning to be had across the charities sector. We’re quite protective of our patch but we can still connect, meet for coffee or whatever and share across the sector. Our CEO, Paul Farmer, is quite visible to the public and that’s great for us as staff to see and from a community and events perspective he’s very involved and does events for us. When I see him on television I do feel that I trust what he says and I’m proud to work for him.

Have the recent fundraising scandals had an impact on you and your team?

Definitely. On a very micro level we have had people say they won’t do events for us or cancelling direct debits. It’s not widespread but it happens. And we respect their right to make that choice. But it’s a drip-feed. You work six hours at an event, standing in the rain and then you hear on the news that all charities are corrupt or whatever and think ‘really?’. It can be quite wearing. It does have an impact but it’s a tricky balance because I don’t want to work in an industry that does bad practice or doesn’t want to discuss its mistakes. So it is healthy to identify where there are problems but it sometimes tips over into misunderstanding or complaints that aren’t backed by evidence. A huge corporation spends hundreds of thousands of pounds on an ad and gets called genius, we spend ten thousand pounds and are told we’re wasting money. But we’re changing the world! So are they, I suppose, but I’d argue our change is better.

As you have a necklace with the word ‘feminist’ written on it, do you think there should be more conversations about feminism and diversity in the workplace, even in charities?

There should definitely be more conversations. Mind is interesting. We’re relatively evenly split gender wise, we may have more women than men. Our gender pay gap is lower than the averages. As a particular cause, we’re more open to the discussions around diversity. Race, sexuality and disability are quite prominent topics in our organisation because of what we do. For example, if you’re a member of the LGBT+ community you’re more likely to be at risk of mental health issues but have less access to services. So it feels quite bedded into our organisation. However, from a staff perspective there’s still more to do but I would argue that because of our cause we’re more naturally aligned to embrace that diversity as we do in services. It’s an interesting challenge for me as a manager. You can’t go back and change an education system that narrows the employment pool, but that’s not an excuse. We’re always trying to look at what we can do to attract more diverse candidates.

Do you work as a fundraiser for a charity? Does it employ the wellness practices that sound so positive at Mind? Does your organisation similarly invest in its staff’s wellbeing? Are notions of diversity, inclusivity and, yes, changing the world key to your mission as a fundraiser?

We’d love to hear your story. Please get in touch by e-mailing joe@sofii.org or adding your voice in the comments section below.