The Foundling Hospital appeal, 1728 – 1745

Thomas Coram was passionate about helping London’s abandoned children. He refused to give up until he’d created a home where they would be cared for and given the chance for a better life. The fundraising methods that helped him realise his dream were innovative then and worthy of our appreciation today.

- Written by

- Tobin Aldrich

- Added

- April 14, 2016

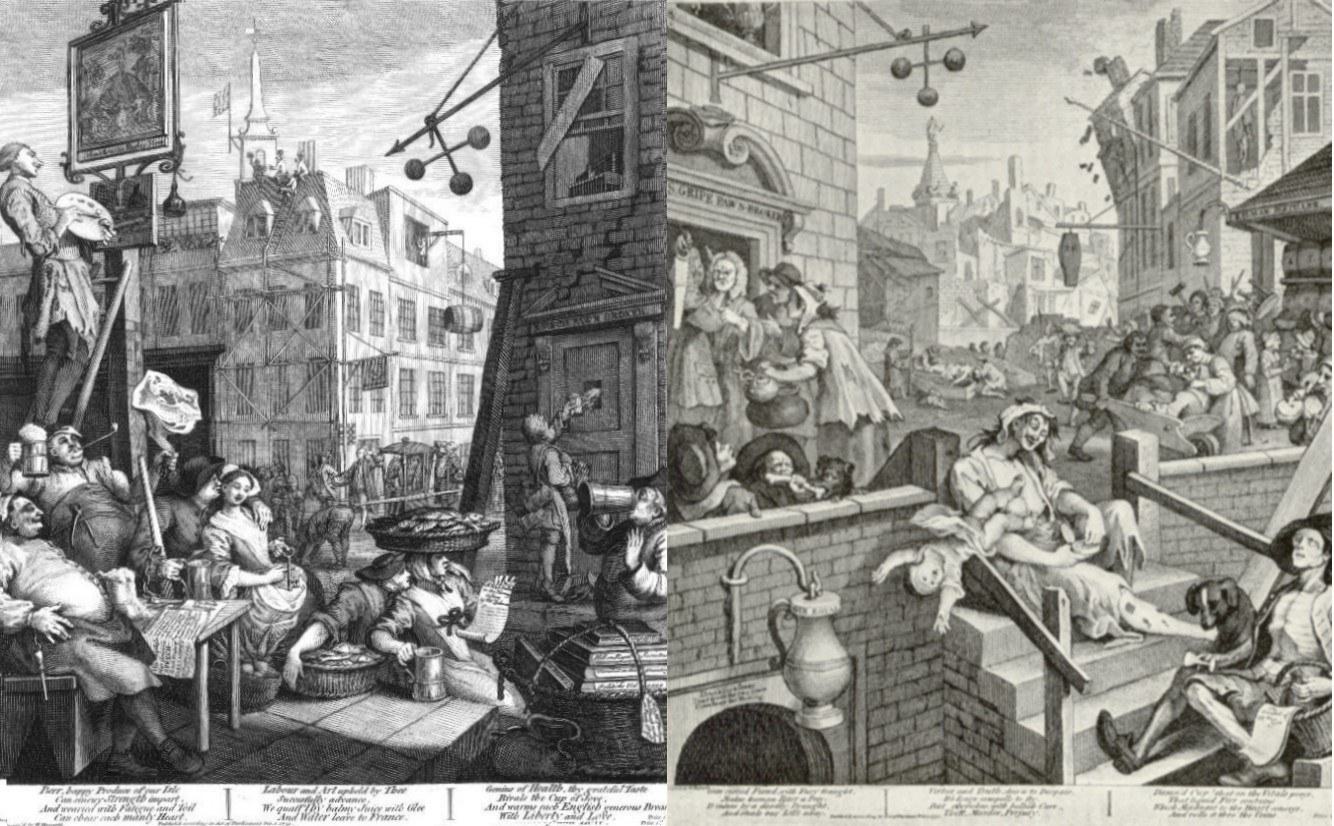

Georgian London was a city with a vast gulf between rich and poor. As great wealth – the loot of empire – poured into the pockets of the elite, the bulk of the population struggled to survive. This was an age where there were no social services and no safety nets. For unmarried women, or their married sisters already struggling to feed the children they had, becoming pregnant was a catastrophe. All too often the result was abandoned newborn children.

A sea captain called Thomas Coram, returning to the city after many years away, was appalled by the number of abandoned infants he saw in London. He was determined to do something to help London’s foundlings. For 17 years, he petitioned London’s great and good to get support to found a hospital to accommodate these abandoned children.

Coram had little joy at first. Lord Walpole called him ‘the honestest, most disinterested person he had ever talked with’ but that didn’t make him a natural diplomat. Or fundraiser. Initially, approaches to the city’s elite were met with a stony response.

But eventually Coram realised that the best way to garner funds from the aristocracy was through the wives of the nobility. Securing the support of the Duchess of Newcastle, the leading society hostess of the age, Coram was able to get London’s wealthiest ladies to sign a memorial, a pledge of funding. With this he was able to get royal approval to establish a Foundling Hospital in 1739.

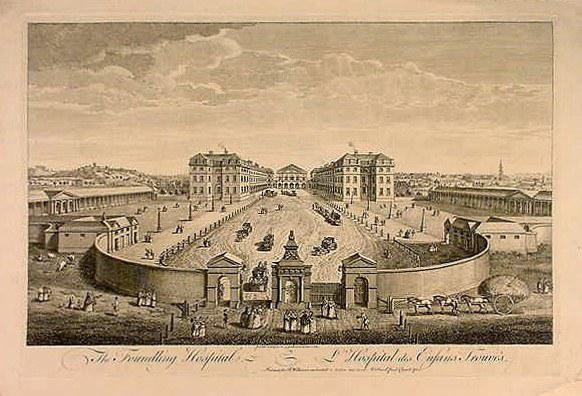

Coram now needed a site. With £7,000 raised from his major donors, he was able to persuade the Earl of Salisbury not only to sell him 50 acres of land in what is now Bloomsbury – but to subscribe £500 to the appeal himself. The foundation stone of the hospital was laid in 1742.

There’s something very recognisable about Coram’s fundraising. He understood not only the importance of major donors but of celebrities also.

William Hogarth, the most famous artist of the period was asked to become a governor of the hospital. Hogarth not only agreed but donated some of his finest paintings, one of which was used as the prize in a fundraising raffle. Hogarth then also asked his friends to donate paintings, establishing the hospital as London’s first public art gallery. The fashionable folk of London would visit the gallery, and having engaged them, they would be asked to contribute to the costs of running the hospital.

Not only this, but Coram may have invented the benefit concert. In 1749 George Frideric Handel performed his new and controversial Hallelujah Chorus at the hospital – with all proceeds going to the foundlings. Such was the success of this concert that it became an annual fixture, raising over £7,000 – enough to buy 50 acres of central London in the 18th century.

Sadly the Foundling Hospital itself does not survive having been demolished in the 1920s. But the charity still does, now simply called Coram and still looking after London’s children from (part of) the same site.

This wonderful appeal was presented at IWITOT London in September 2015.