Founding of the British Red Cross: a spectacular result from a letter to a national newspaper, 1870

- Exhibited by

- SOFII

- Added

- June 20, 2011

- Medium of Communication

- Direct mail.

- Target Audience

- Awareness, individuals, social change campaign, volunteering.

- Type of Charity

- Healthcare, international relief / development, public / society benefit.

- Country of Origin

- UK.

- Date of first appearance

- July, 1870.

SOFII’s view

This is an important piece of fundraising history. It explains how one of the world’s most significant international humanitarian organisations took root in the UK. Also, it records the moment when a brief correspondence in a leading national newspaper of the day showed the British public’s extraordinary capacity to react with inspirational generosity at a time of evident need.

Creator / originator

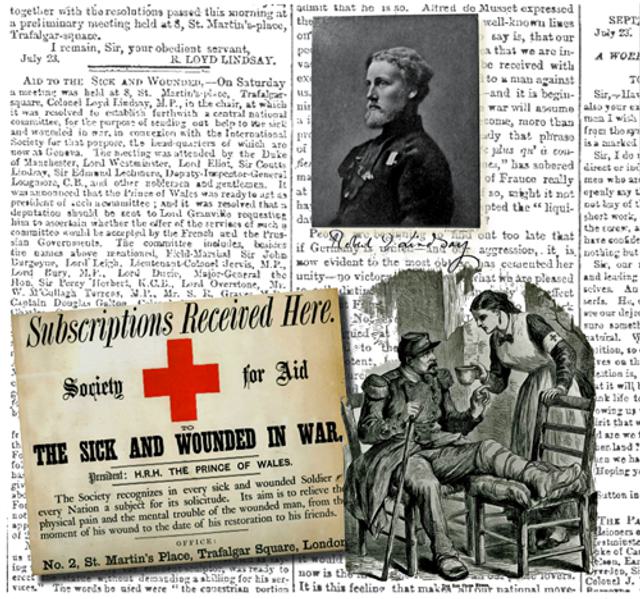

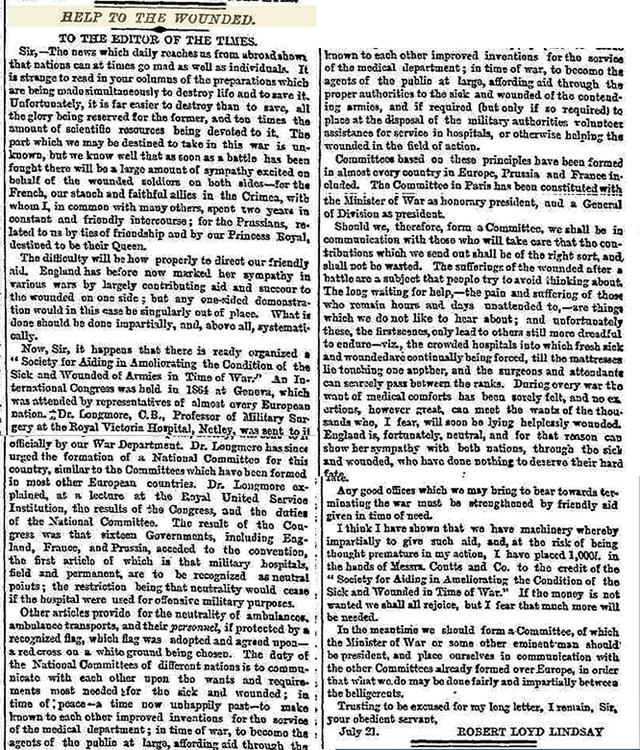

The British Red Cross was founded in 1870 after a letter by Colonel Robert Loyd-Lindsay was printed in The Times. Colonel Loyd-Lindsay had been a soldier during the Crimean War where he earned one of the first Victoria Crosses. His experiences had convinced him of the inefficiency of the army’s hospital provisions. He studied the Geneva Convention and was convinced that the presence of an organised Red Cross Society in the Crimea could have saved many lives. When war broke out between France and Prussia he was approached to help found a British Red Cross Society. He wrote a letter to The Times on 22 July 1870 explaining the need for such a society and publicising his own starting contribution of £1,000.

‘The difficulty will be how properly to direct our friendly aid. England has before now marked her sympathy in various wars by largely contributing aid and succour to the wounded on one side but any one-sided demonstration would in this case be singularly out of place. What is done, should be done impartially and, above all, systematically.’—From Colonel Loyd-Lindsay’s letter to The Times, July 1870.

Background

In 1859 Swiss businessman Henry Dunant saw the aftermath of the Battle of Solferino in northern Italy and was appalled by the lack of medical facilities for the wounded. His experiences – he actually worked alongside local women to help the 9000 wounded who struggled into the town – led to the idea of a series of peace-time relief societies that would be constantly ready to give care to the wounded during wartime. The idea was supported by the Genevese Society for Public Welfare, which organised the first Geneva Conference in 1864. At this conference the first Geneva Convention was signed, authorising the use of an international flag to identify official hospitals and doctors, and to protect them and the wounded they cared for. The societies set up by the convention continue today as part of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement.

£250,000 still sounds like a lot of money, of course. But back then it was vast – its equivalent today would be in the region of £17 million. Not bad for a letter to a newspaper!

Special characteristics

Through its appearance in one of the country’s leading newspapers, Colonel Loyd-Lindsay’s letter reached a huge number of people. The letter mobilised support that was already building after Florence Nightingale’s work in the Crimea and the signing of the Geneva Convention by offering it a clear focus. By including details of his own financial contribution in the letter, Loyd-Lindsay offered both a moral example and a practical example to ensure that people contributed to a single fund.

The letter’s wording emphasised the society’s founding principles of neutrality, impartiality and co-operation. The need for immediate action was highlighted by passionate descriptions of the suffering of the wounded, obviously drawing from Loyd-Lindsay’s own experiences.

Influence / impact

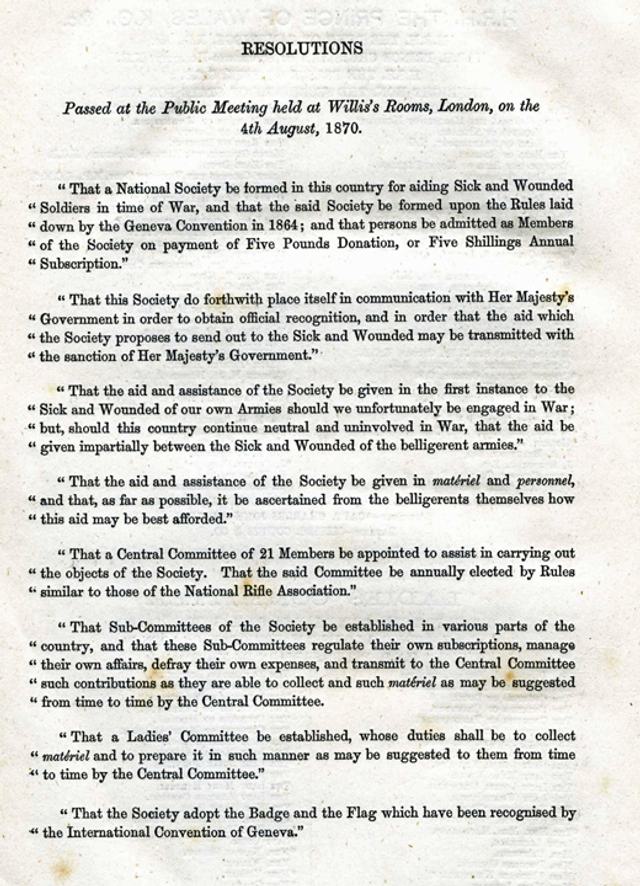

Within a fortnight of Loyd-Lindsay’s letter appearing in The Times a public meeting was held in St James’, London. This meeting saw the foundation of the National Society for Aid to the Sick and Wounded in War on principles laid down in the Geneva Convention of 1864 with the international flag of a red cross on white background. Aid was immediately sent to France and Prussia in the form of staff, ambulances and gifts donated by local committees.

Since 1870 the British Red Cross has served in many conflicts, including the First and Second World Wars, the Korean War and the Falklands. It has also set up services providing emotional and practical support in Britain, including the first blood transfusion service and the fire and emergency support service.

Results

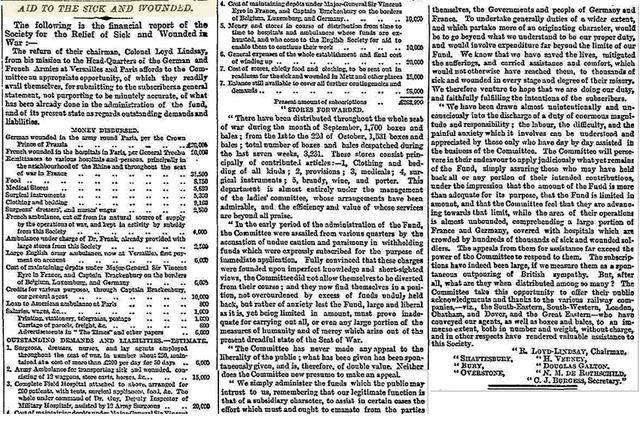

As a direct result of Loyd-Lindsay’s letter £30,000 was raised by the end of August 1870. Within a month over 40 surgeons were working overseas. By the end of the war £250,000 had been subscribed with £8,000 spent on surgical instruments alone. £250,000 still sounds like a lot of money, of course. But back then it was vast – its equivalent today would be in the region of £17 million.

Not bad for a letter to a newspaper!

Merits

Loyd-Lindsay’s letter is remarkable for the response that it generated. It managed to build on a general desire for a Red Cross Society and was immediately effective. However, more important is the fact that the Society continued after the immediate crisis had passed. The British Red Cross has been active since 1870, initially in response to conflict, but from 1919 as a peace-time organisation as well.

Other relevant information

Colonel Loyd-Lindsay’s comments are remarkable particularly for the even-handed, neutral, international approach that he advocates, which for the time was quite visionary. He wrote:

‘The news which daily reaches us from abroad shows that nations can at times go mad as well as individuals. It is strange to read in your columns of the preparations which are being made simultaneously to destroy life and to save it. Unfortunately it is far easier to destroy than to save, all the glory being reserved for the former, and ten times the scientific resources being devoted to it.

‘The part that we [the British] may be destined to take in this war is unknown, but we know well that as soon as a battle has been fought there will be a large amount of sympathy excited on behalf of the wounded soldiers on both sides for the French, our staunch and faithful allies in the Crimea, with whom I, in common with many others, spent two years in constant and friendly intercourse, and for the Prussians, related to us by ties of friendship, and by our Princess Royal, destined to be their Queen.

‘The difficulty will be how properly to direct our friendly aid. England has before now marked her sympathy in various wars by largely contributing aid and succour to the wounded on one side but any one-sided demonstration would in this case be singularly out of place. What is done, should be done impartially and, above all, systematically.’

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

Also in Categories

-

-