Harvesters Food Bank’s fundraising strategy

- Exhibited by

- Adrian Sargeant

- Added

- July 07, 2015

- Medium of Communication

- Fundraising Strategy

- Target Audience

- Type of Charity

- Country of Origin

- USA

- Date of first appearance

- 2001

SOFII’s view

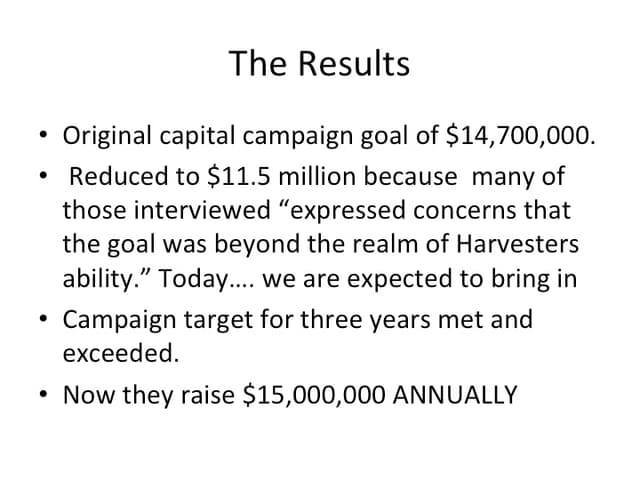

Harvesters ambition was huge: to increase their support from $2 million to a massive $11.5 million. That they achieved it must be in part because they believe ‘people don’t want to give money away, but they do want to make a difference in other people’s lives’. Harvesters showed their donors exactly how they can make a difference to hungry people in their community.

Creator / originator

Joanna Sebelien

Summary / objectives

Founded in 1979 Harvesters is currently the only food bank serving North West Missouri and Eastern Kansas It serves as a clearing house for the collection and distribution of food and related household products and serves local people by:

- Collecting food and household products from community and industry sources.

- Distributing those products and providing nutrition services through a network of nonprofit agencies.

- Offering leadership and education programmes to increase community awareness of hunger and generate solutions to alleviate hunger.

Background

When Joanna Sebelien first joined Harvesters as the manager for their capital campaign in 2001, $1 million had seemed like a lot of money. Her immediate priority had been to raise the capital necessary for a substantially larger warehousing and distribution facility. At the time the $11.5 million this would require had seemed like a giant and perhaps unrealistic leap forward for an organisation that was generating an annual income of only $2 million.

The 2001-5 campaign

Reaching agreement over the campaign goal of $11.5 million was not easy because of the difficulty in projecting likely need. Population growth, changes in welfare and a generally poor economy all had an impact. In recognition of this, in 2000 the board had undertaken a major review of the strategic direction of the organisation, working with the Rockhurst MBA programme.

The Rockhurst team conducted surveys of Harvesters agencies gathering data on the percentage of their need that Harvesters was filling and how this was likely to change. They then offered a series of recommendations about how much of that need Harvesters should fulfil. This analysis made it possible to examine how best Harvesters might gear up its operations to meet this target and remain relevant to the needs of its community.

The board also formed a group to look at planning the ‘facilities of the future’, which explored what they were going to need, how to get there and how long it would take. Options for developing service provision included expanding the current facility, looking for efficiency gains, creating a completely new facility, or improving the terms on which they operated with suppliers.

To narrow the alternatives the board conducted a benchmarking exercise of 10 other food banks, quickly identifying that Harvesters were actually one of the best, moving a high volume of food for the square footage of warehouse space available. They concluded that it would be unlikely that sufficient efficiency gains or improvements in terms could be found to allow them to meet all the future demands on the organisation. In addition, since it was impractical to build further on the existing site, the only viable option was to develop an entirely new facility.

Harvesters are also a member of Feeding America, a nationwide network of more than 200 food banks, providing professional development, advocacy for hunger issues and, critically, a periodical study of ‘Hunger in America’. Through Harvesters could paint a rich picture of the kinds of people an enlarged distribution facility would enable them to reach. Such data were later to become important in shaping the case for support for the campaign. They had been clear on the need for this underpinning from the outset. The campaign they were about to run was not to be about raising money for a building, it was to focus instead on asking supporters to help them position themselves to meet the increased need that the Kansas City community was shortly to be facing.

Sebelien remembered an early conversation with Bob Hartsook, the consultant they had engaged to guide the campaign. He had been very clear that ‘people don’t want to give money away, but they do want to make a difference in other people’s lives’. Carefully delineating the nature of that difference and being able to communicate it successfully to donors had been central to the success of the campaign. Too many food banks, she recalled, were still at the level of raising money for an additional driver, a new truck, a new dock, or the minutia of the mechanics of their operation. They had forgotten that the end result, the reason for their existence, was actually feeding people.

This focus on need wasn’t the only thing that had been different about the 2001-5 campaign. Prior to 2001, Harvesters, like most nonprofits, had drawn a firm distinction between its operating costs and the need for additional funding for capital projects. A capital campaign was thus regarded as a distinctive entity, separate from annual fund fundraising. Sebelien and Hartsook together had quickly recognised that maintaining this distinction was unlikely to be helpful. The new warehouse facilities the organisation needed required a substantive investment of $11.5 million. This figure dwarfed the organisation’s current requirement for operating funds creating two distinct challenges.

First, fundraisers had been used to having conversations with donors about specific campaigns and asking for either operating or capital support. Given the scale of the requirement for capital funding there was a very real risk this could siphon off equally vital operating support.

Second, the creation of a much larger facility would dramatically increase the need for this operating expenditure. As soon as Harvesters were able to move into their new building they were going to need additional funding for basics such as heating, lighting and staff, and everything was going to grow. Alongside the capital campaign it would, therefore, be necessary to increase the organisation’s fundraising capacity to sustain this into the longer term.

Special characteristics

Hartsook’s firm had been the only agency to suggest the innovative solution of an integrated campaign. As Harvesters looked forward they talked to donors about need, rather than specific categories of campaign and talked about this need into the longer term. Harvester’s research had provided a clear window on what this would look like and the capacity that would be necessary to meet it. It made little sense to talk to donors in terms of annual goals or, in the case of capital, the facilities they hoped to purchase or create. Rather they were able to use their strategy to create a vision by the end of the campaign of how many families would be fed, how many children and so on.

Gifts were therefore solicited in terms of these ultimate targets and thus for a multi-year commitment. The gifts Harvesters had to solicit were much bigger as a consequence, but donors were able to understand the approach because they knew exactly what their support would achieve. The multi-year approach also offered a significant advantage to the organisation since it was able to preserve precious fundraising resources by not having to talk to donors each year in the hope of persuading them to ‘renew’ their support.

Putting together the budget for the campaign was a challenge because Harvesters were not used to thinking in this way. All categories of cost now had to be projected so that they could be included in one integrated campaign. In so doing the organisation was able to factor in its desire to increase its capacity to raise operating monies, while at the same time securing all the capital necessary to secure the expansion. Projecting cash flow was a particularly delicate exercise since management had obviously to ensure that the requisite funds were available to fund both existing service delivery and the planned expansion that would take place in any given year.

Merits

Because many organisations are too focused on their campaigns – and they forget that no one inherently wants to give to an annual fund, capital campaign, or endowment. Rather, donors care about the impact that the work of the organisation can have in their community. This case tells the story of one such reorientation and the dramatic impact it had on the organisation’s fundraising success. In 10 years it moved from funding a total annual operating budget of around $2 million to successfully achieving an $11 million and then a $35 million ‘integrated’ campaign.

This campaign was showcased at SOFII’s I Wish I’d Thought of That in Baltimore

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

View original image

Also in Categories

-