Live Aid: the history of an all-time great event

- Exhibited by

- Sarah Bond

- Added

- March 31, 2011

- Medium of Communication

- Event

- Target Audience

- Awareness, individuals, single gift, social change campaign, volunteering

- Type of Charity

- International relief/development, poverty/social justice, public/society benefit

- Country of Origin

- UK

- Date of first appearance

- July 1985

SOFII’s view

Live Aid was perhaps the most successful fundraising event in history and we thought it was about time it was on SOFII. With live music, celebrity endorsements and a worldwide audience, Live Aid was able to raise an unprecedented amount of money that even today has not been surpassed. Putting on an event the scale of Live Aid might be beyond most of our capabilities, but the impact of having a strong and compelling ask and being able to appeal to and capture the imagination of a mass audience are lessons that are just as valuable today.

Creator / originator

Bob Geldof, Midge Ure and Harvey Goldsmith

Summary / objectives

Live Aid was a music concert held simultaneously in London and Philadelphia to raise money, from ticket sales and direct donations, for the people who were victims of the Ethiopian famine.

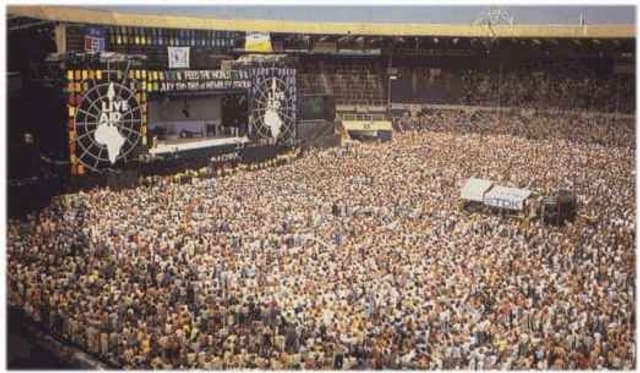

The event was only 12 weeks in the planning, in which time 58 bands were brought together to play live music over 16 hours, across two venues, attended collectively by over 170,000 people. Broadcast live to the world, via 13 satellites, the event was watched by an estimated two billion people.

On the same day, inspired by the initiative, independent concerts were also held in countries including Australia and Germany.

Background

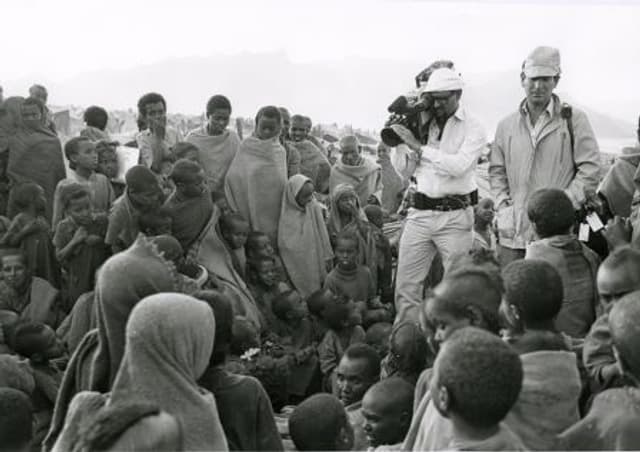

The concert was conceived as a follow up to the previous Geldof/Goldsmith project, the successful charity single ‘Do they know it's Christmas?’ This saw Geldof mobilise the pop world in response to a news report he had seen on the BBC about the famine in Ethiopia. The record was performed by a collection of British and Irish music acts billed as 'Band Aid' and had been released the previous winter. At the time it was the UK’s best selling single and raised an estimated £8 million.

As Geldof began to learn more about the situation in Africa over the following months, he discovered that one of the main reasons why African nations were in such dire peril was because of repayments on loans that their countries had taken from Western banks. For every pound donated in aid, ten times as much would have to leave the country in loan repayments. It became obvious that one song was not enough.

Special characteristics

Aside from being one of the largest satellite link-ups and television broadcasts of all time (its closest rival being the royal wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana four years earlier with a miserly 750 million viewers), Live Aid was an entirely new phenomenon for the fundraising world.

Live Aid wasn’t ‘charity’ in any traditional sense of the word. For Geldof, helping the people of Africa who were dying because of the famine was without doubt a worthy reason for putting on such a maverick event but it wasn’t supposed to be charity, as he later explained, ‘Calling it charity drove me nuts. For me this was finely tuned politics.’

For the people who went to the concert, or were watching on their televisions at home, it wasn’t charity either – or at least, didn’t feel like it. It was pop stars and culture and history in the making. It made giving money to Africa feel trendy, a far cry from the usual appeal landing on the doormat.

With two billion people watching live in 160 countries, people were able to share and participate in the same event. In a field in Cheshire, 5,000 people watched the concert unfold on a big screen erected for the occasion; they spent the afternoon as a community collectively raising money too. But the event went beyond local communities, it brought people together across continents, making them feel part of a global village: one humanity.

Live Aid was unique in that something like this had never been attempted before. People got caught up in the curiosity of such an event, as well as the compassion that lay at its heart. Even at the time, the historical significance of what Geldof was attempting resonated with countries and cultures across the world.

Influence / impact

The event certainly had an impact; Bob Geldof shouting expletives live on the BBC has a tendency to live on in people’s memory and the history books. Against popular belief, Geldof didn’t actually say, ‘Give us your f***ing money’, but what he did say was equally powerful.

Having stormed up to the broadcast box on hearing that, after five hours, they had raised a paltry one and a half million pounds, he sat on the couch in front of the camera and said, ‘There are people dying now, so give me the money.’ For a lot of people, having to ask people for money is the awkward and mildly embarrassing bit, fortunately Geldof had no such qualms.

The swearing came after his alarming request, when the presenter insisted that the address to which people could send their money needed to appear on the screen before Geldof gave out the number to call. Knowing full well that only by allowing people to respond immediately to the call for action would significant amounts be raised, he took offence, expostulating, ‘f*** the address!’

Whichever way it is remembered, the impact of Geldof’s words is undeniable and it triggered an immediate surge in donations.

But whilst Geldof’s infamous words may be up there with the most memorable moments of Live Aid, another even more effective tactic stole the show entirely, moving people to unprecedented levels of giving.

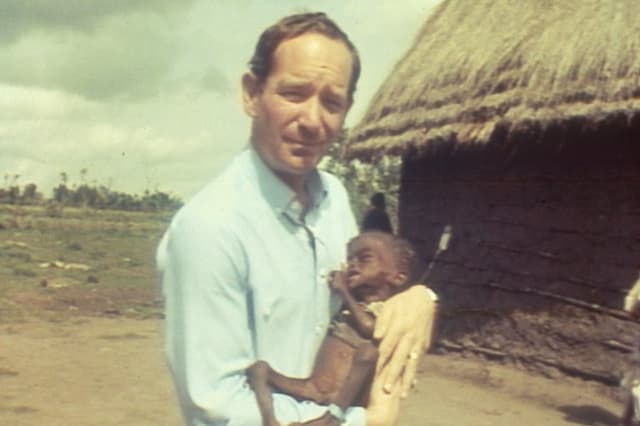

A short video laying bare the desperate conditions families were facing in Africa was shown at the end of David Bowie’s set, who had made the decision to cut one of his songs to allow time for it to be shown. The pictures of starving children shocked the world into remembering the reason the event was being held. Immediately after the video was shown, donations came in at over £20,000 a minute. These kinds of images have now become synonymous with television charity appeals, but for the Live Aid audiences in 1985 it was a ground-breaking moment and their response ensured the formula would be used many times over.

Results

It is thought that the organisers’ initial target was to raise £1 million. The final figure raised from Live Aid is estimated to be around £150 million (which is equivalent to £350 million in today’s money).

Other relevant information

In 2005, Bob Geldof and Midge Ure announced the Live 8 project. Based on the original Live Aid premise of pop culture impacting on politics, live concerts were organised in cities across the industrialised world, including London, Paris, Berlin, Rome, Philadelphia, Tokyo, Moscow, Johannesburg and lastly Edinburgh, to coincide with the G8 economic summit of world leaders at Gleneagles.

Unlike Live Aid, these concerts were not intended to fundraise but to raise awareness of issues burdening Africa, including government debt, trade barriers, hunger and AIDS. The concerts were free, although around £2.5 million was raised from a text message lottery for tickets.

An estimated 1.5 million people attended the concerts in person and more than 30 million signed up to the text and web petition, the Live 8 List. Six days later, attendees of the G8 summit announced a commitment to provide an additional £28.8 billion in aid for Africa as well as measures to help debt, trade and health.

Click here for some reflections on the Live Aid phenomenon from Irish fundraising superstar Damian O’Broin, ‘A seminal moment for my generation’.

SOFII’s I Wish I’d Thought Of That 2012 – Rebecca Mauger presents Live Aid.

Also in Categories

-

- Events and Community