CDE project 13 section 3: the theory

- Written by

- The Commission on the Donor Experience

- Added

- April 28, 2017

Part Two: The Theory

Let’s start at the very beginning…

Before getting into the specifics of donor preferences, choices and control let’s begin with the principles of human behaviour that govern how people make decisions.

As direct response copywriter Andy Maslen neatly puts it, we are not in the marketing or fundraising business. At the most fundamental level, we are in the business of “behaviour modification”.

We seek to influence someone to choose to change their course of action. To click that petition. To type in their email address. To request a brochure. To give a donation.

Each of these things constitutes an action. Prior to coming across our fundraising communication – be that a website, a chat with a street fundraiser, a direct mail approach, a Facebook post – in the wider world life goes on.

Our challenge is to identify people who we feel may share our commitment to our cause. They may see themselves in the good fight our charity fights.

True engagement with a charity’s message is an emotional connection: a shared belief and viewpoint that stops someone in their tracks and catches their attention.

To help demonstrate this, consider the very basic units of drama. The smallest unit is called a ‘beat’. Several beats create a scene. Several scenes create an act. And so on. A beat can be broken down in three parts: action, conflict and resolution.

This maps very helpfully with a model posited by creative director Steve Harrison in his book, How to do better creative work. He calls it the ‘problem/solution dynamic’ – in other words, the equivalent of the conflict and resolution stages.

Let’s bring this to life. At any moment in time, people (our potential donors) are going about their daily lives (action). They engage with a piece of communication that catches their attention because it speaks of a need that matters to them (conflict) and they are stirred to do something - be that financial, voluntary or other action - to help make a practical difference (solution).

Action, conflict (problem) and resolution (solution). Three simple steps at the heart of how we communicate. And in fundraising terms, three steps which bring the donor and the charity together for mutual benefit.

But the crunch point in this journey is the moment of conflict/presenting a problem for a person to help solve.

You’ve caught their attention but what next? Is your aim simply to heighten their awareness (say, through a brand advertising campaign on checking symptoms of an illness)?

Or do you wish to stir them to take action there and then (e.g. text whilst on the train) or, once home, sign up or take an action online (e.g. a sponsored run)?

This is the moment where a ‘suspect’ becomes a ‘prospect’ – from a passer-by to a ‘handraiser’ telling you “I believe in your cause”. So much hinges on the decisions made in this moment.

And as behavioural science teaches us, a great deal of it is far more complex, subliminal and irrational than we might think.

This project report is not the place to unpack the vast and fascinatingly nuanced discoveries of behavioural science in technical detail – books and papers by Daniel Kahnman, BJ Fogg and Richard Thaler should be your first port of call for the fully tested methodologies.

But here we will provide a whistle-stop guided tour, in layman’s language. Because as we’ll discover, the implications on preferences, choices and control are significant.

So here we are. With our prospect, at a crossroads.

A potential supporter has a dilemma to ponder. Whether they are sufficiently emotionally affected and rationally reassured to take an action that supports your charity’s cause, whatever that action may be.

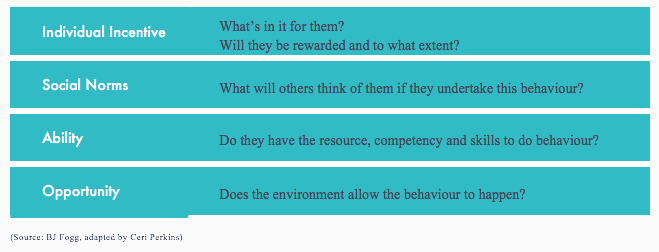

How can you make sure someone takes the action desired? The equation looks like this, as distilled in Adam Ferrier’s The Advertising Effect:

Action = Motivation + Ease

Each of these three components, collectively, form the bread and butter of this theory section of Project 13.

But to give a short written explanation first: Motivation covers the desires, goals, emotions, social patterns and beliefs that inform who we are. They are the makeup of a person’s character. Their background, their temperament, their interests and passions.

Ease concerns factors like the environment in which you present someone with a choice (on the street, on a landing page, in an insert, for example). And that environment can be affected by a myriad of factors. In other words, context is everything when it comes to making decisions

Visual: The component of motivation + ease

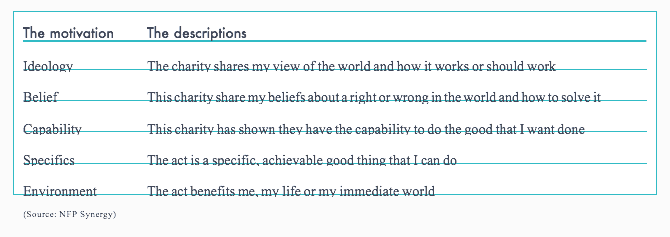

Table: What motivates people to join your charity’s cause?

Let’s take a sign up landing page for an example.

How is it designed? Is the user experience of the form intuitive? Does the accompanying copy present sound benefits? What will a person receive in exchange for their data? Can the prospect get a taster of what they will receive (or are they offered an incentive for signing up)?

Then there are the dull practicalities that can also make or break whether the decision environment is optimal. How quickly does your website load? Does it break mid-flow? Is the back-end functioning set up so that sometimes no matter how hard a person tries, they receive error messages while they try to donate?

And if there weren’t enough barriers, does your potential recruit have the knowledge and skill to complete the action you’re asking of them? There’s a reason paper donation forms are still a staple part of campaigns to an older age cohort; a text to give request is not something that would sit comfortably within that group’s technical capabilities.

We’re just scratching the surface. But already you can see how in each step along the way there are so many potential barriers to someone responding to their need to act, making a decision and being able to follow that through to its completion.

Traditionally, our industry – and the marketing sector as a whole – has placed a huge amount of emphasis on the first part of this equation, motivation. This is doubtless an important area to address but very often, what’s stopping someone from seeing their decision through is far more basic. It’s about how easy it is to do.

It’s fair to say that all evidence in this field of study points to an amusing truth: we are, as a species, inherently lazy. We like things to pootle along just as they are, thank you very much. The reason why is simple: there are just too many decisions our brains need to make every millisecond of every day. Or as niftily expressed by Thomas Davenport in The Attention Economy, human bandwith “is finite”.

This tendency to laziness you sometimes hear referred to in smarter circles as ‘inertia’ or a reliance on ‘defaults’. Any form of direct debit is an ingenious model based on defaults. Because it’s just that bit too much effort to cancel your gym membership, isn’t it? So you continue to not go whilst paying for the privilege and feeling increasingly guilty…

It’s the reason why most charity donation pages aren’t as effective as they could be. If you’re getting a bounce rate of 60 per cent, that means 60 per cent of people who made a decision to give and tried to give, weren’t able to because of your site. Imagine if, as a shop owner, 60 per cent of your customers in a day came up to pay at the till but, due to a machine fault, were turned away completely? You’d consider it commercial suicide. Yet it’s a common problem online. If it’s too much effort, you turn people away.

So, without question, making it easy for people to engage really matters – as much as understanding their motivation.

Daniel Khaneman’s experiments, documented in his book Thinking Fast and Slow, posit two systems of thought: System 1 (automatic) and System 2 (processed). An example of System 1 is opening the doors to your flat. It’s a habitual routine; you do it without even thinking. It’s a heuristic; a shortcut in your ‘thinking’ circuitry.

System 2 is much slower. It’s the stuff that needs lots of thought. Doing your tax return. Choosing a car. Things that aren’t part of your day to day rituals, require deeper consideration, involve higher risk and take more time to process.

“We are all creatures of our environment”,

says Paul Dolan, psychologist and author of Happiness By Design.

“Much of what we attend to, any resulting behaviour, will be driven by unconscious and automatic processes… So any attempts to understand human behaviour and happiness must properly account for the effects of external context as well as internal cognition.”

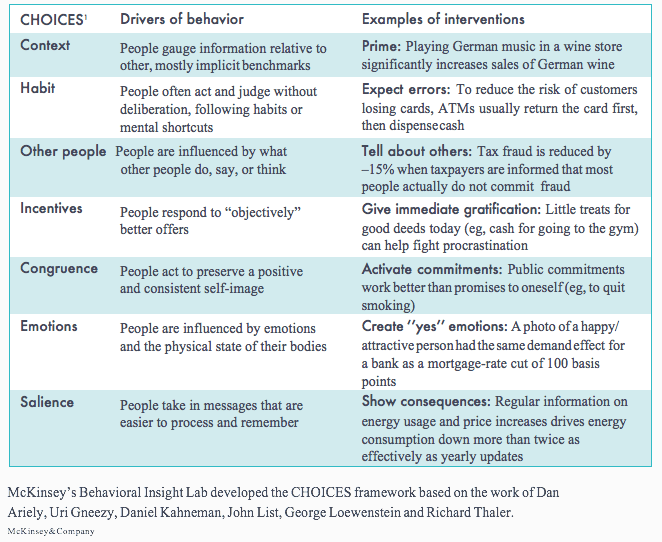

Sound familiar? Here we have another pair of phrases - external context, internal cognition – that cover ease and motivation. These principles ring true regardless of the sector. Here’s one model of decision-making created by McKinsey for the commercial sector. Pay close attention to the column marked ‘Drivers of behaviour’. Consider how these principles apply to your charity:

Table: McKinsey Choices Framework

The CHOICES framework of behavioral drivers created by McKinsey’s Behavioral Insight Lab helps determine relevant interventions.

Seeing things from the donor’s perspective

As charity fundraisers, we like to think that our cause and especially our latest campaign sit at the centre of the universe. Perhaps for the most committed advocate that may be true.

But for the majority there’s a thicket of other stuff our message needs to cut through – job anxieties, family duties, ill pets, the list goes on.

Therefore not only do we need a message that can grab their attention amidst all this competing paraphernalia (by knowing what motivates them). Once we’ve got their attention, it has to be straightforward to do (make it easy).

And the point at which someone decides to tell a charity their choices or preferences is the most critical moment of ‘conflict’ of all.

Let’s take a second, though, to clarify what we mean by preferences and choices. The two are often confused. To help us, here are the definitions according to the Oxford English Dictionary:

Choice. An act of choosing between two or more possibilities.

Preference. A greater liking for one alternative over another or others.

Let’s again use a sign up page as example. In addition to inviting him or her to share contact details, you offer a prospective supporter the chance to receive a) your weekly newsletter and b) your e-appeals. These are the two choices you have presented. But whether a person picks one, the other or both cannot be assumed a preference.

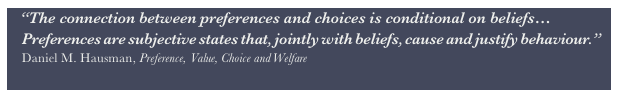

This is because a preference, as economist Daniel Hausman explains in Preference, Value, Choice and Welfare, is comparative: “To prefer something is always to prefer it to something else… preferences require that one weigh alternatives.”

So let’s first debunk a common assumption: that by asking supporters to tell us their preferences, we are doing exactly what they want. We are not.

We are learning what a supporter wants out of the menu of options we, at the charity, are presenting them with. Those choices do not necessarily reflect every choice a supporter may wish to have.

And what do we mean by a preference in a charity context? To give a few examples, from a communications standpoint we might be referring to:

Channels.

How would they like us to be in touch with them? By email? By phone? By SMS?

Frequency.

How often would they like us to be in touch? Weekly? Monthly? Annually?

Message Content.

What types of information is of interest to them? Newsletters? Appeals? Sponsored events?

Why do we offer people choices and ask them to share their preferences?

The benefits can be numerous but they all add up to one big advantage: relevance.

This, like engagement, can too often feel like a wishy-washy term bandied about to sell consultancy with a high price tag. But as inspirationally defined by Nina Simon in The Art of Relevance, it’s simply

“Killer content. Unspoken dreams. Memorable experiences. Muscle and bone.”

Still think that’s a bit too wishy-washy? Then let’s hark back to our behavioural science friends for proof.

Lives are busy. There are far more important fish to fry than your charity’s cause. Unless what you are promising to give me, in exchange for my support, is going to enrich my life.

Hands up if your warm email programme consists of one newsletter sent to your entire base? That, unfortunately, is not communicating with relevance.

If, however, your content is based on the explicit preferences someone has shared with you (I want the newsletter; I’m interested in your international projects)…

…And you are overlaying that with their behavioural data (Where have they been on your site? Where do they drop off? What content have they engaged with?)…

…And you overlay their giving history captured in your database (RFM/LTV analysis)…

..And you are reading letters sent back to you from donors, listening to inbound calls, sitting in on focus groups and interviews.

...then, and only then, are you truly taking relevance seriously.

When less is more

Being more relevant may mean communicating less but with far greater meaning. As a recent fundraising test by Kevin Schulman at DonorVoice proved,

“Less is more when the ‘less’ is determined by understanding donor identity and preference and serving up content, offers, interactions, communications that match it. If this is starting to seem a lot like personalised relationship building, that is because it is.”

This approach is many moons away from where most charities are currently. The systems aren’t there. The data is not in good enough shape. Preferences are sometimes being captured but not truly driving what happens next.

What we’ve just walked through builds and builds to a seeming obvious, but crucial, insight about choices and preferences: offering them and having them are not the only thing that matters.

If a personal, relevant and engaging communications relationship with our donor is the holy grail we are aiming for, they are just one part of a much bigger picture. Offering choices does not make a charity donor-centric: it is simply a means to understanding what your donor wants so that you can meet their needs, wishes and interests as fully and as well as you can.

And as your relationship with a supporter develops over time, circumstances may change and preferences be amended and updated accordingly. But it is just one part of a much bigger tapestry of how to be relevant to your donors and show you are listening.

As we’ve all experienced, there’s nothing more frustrating than being asked to make a choice (automated telephone banking menus, anyone?), stating your preferences only to find nothing has changed.

No matter how worthy your cause, your prospects and donors will drop you if you don’t follow through on the expectations set and the promises made.

So now we’ve hit upon the two things preferences can really bring to the table: they can help us be relevant to our supporters and provide them with a way to feedback.

Preferences are an opportunity for us to listen.

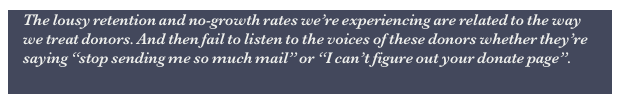

Perhaps “listening”, too, feels a little soft for our target-riddled, Excel-driven fundraising culture. But, as Roger Craver pointed out on Fundraising 101, we’ve all paid the price for ignoring donors in recent years:

So let’s dig a little deeper into the science of motivations to understand why this can make or break the psychological processes that underpin how donors tackle choices and preferences.

Understanding supporter motivations

Hausman’s assertion rings true when you consider the irrational processes behind how we all make decisions. But we aren’t wired to always make the optimal decision, referred to as ‘maximising’. Instead, in our lives we mostly ‘satisfice’. We settle for good over great.

If we are honest with ourselves as a sector, responding to a charity’s request for our preferences – whatever the context

is not something that anyone will deeply ponder. People want to sign up, update their information or end their relationship as quickly and painlessly as possible. They then quickly move on to the next thing vying for their attention.

Which means that an awful lot of seemingly ‘soft’ subjective factors suddenly become of great importance, as they can sway selections at the moment of decision. Have I heard of the charity? What do I remember of recent interactions with them? Does what they say I’ll receive in exchange for my data excite me? What does expressing my support say about me to others in my social group?

We are now in the underappreciated realm of ‘beliefs’. What Matthew Lieberann, a psychologist at the University of California, defines as the “mental architecture of how we interpret the world”. As The Guardian fundraising columnist Beth Breeze explains,

“Taste is not simply a matter of what we like; our present day choices are also shaped by earlier life experiences…”.

As fundraisers, there’s a lot we have to get right to reinforce or change beliefs in order to cue the desired action. And, let’s be clear, emotions do drive actions. As Daniel Goleman’s scientific studies in Emotional Intelligence reveal:

“All emotions are, in essence, impulses to act…The very root of the word emotion is motere, the Latin verb ‘to move’ plus the prefix ‘e’ to connote ‘move away, suggesting that a tendency to act is implicit in every emotion".

His work goes far beyond a useful definition; Goleman’s experiments proved that

“our feelings typically come to us as a fait accompli. What the rational mind can ordinarily control is the course of those reactions.”

In other words, perception truly is more important than reality. Folks in the branding world have known this in their bones since the beginning. And as there’s now plenty of science to prove it, we fundraisers can now give it the attention it deserves. We can bake it into how we treat our prospects, supporters and donors.

As Rogare’s detailed study of relationship fundraising concluded,

“Everything we know about how to build a good relationship - as apparent for friends - we can apply to fundraising”.

Now we’ve understood just how closely emotions are tied to beliefs, let’s move on to trust.

Trust in me

Research conducted by the Royal Mail Trust in 2015 found that 40 per cent of customers were hesitant to give their data to marketers because they felt they would then be ‘contacted too often’. In fact, the report goes further with this damning insight: “Respondents felt that providing contact details would not lead to more relevant, timely and appropriate communications, just more of them.”

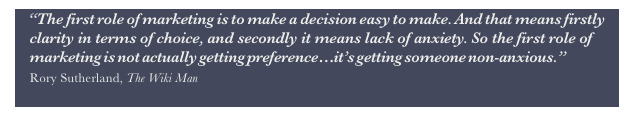

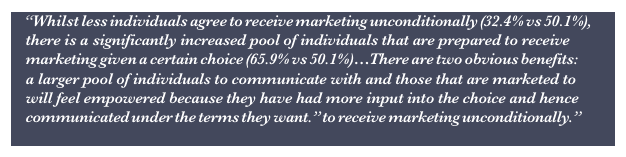

This is further substantiated by recent Fastmap research (October 2016) into customer attitudes to choice:

So let’s keep looking at what really matters to audiences, particularly those who support charities. We’ll do this by comparing the key findings of two recent independent studies:

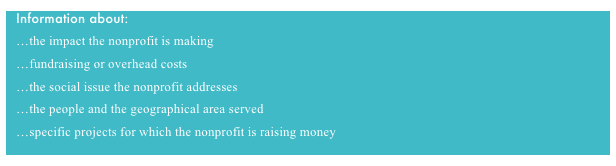

What matters most to donors (Source: Abila Donor Engagement Study)

What information do donors want (Source: Rootcause)

Now, just for comparison, let’s look at a piece Bloomerang conducted on why we tend to lose donors…

Why do donors leave? (Source: Bloomerang)

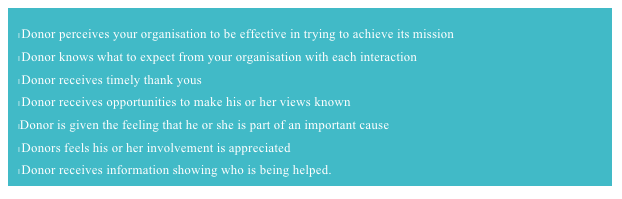

And if the donor concerns weren’t already ringing loud and clear, here are Roger Craver’s Seven drivers of donor satisfaction, detailed in his book Retention Fundraising, based on a study involving over 2,500 charities in the UK and US:

There are two things to take from all this. First, the overlap of key donor concerns across the studies is not coincidental. We keep hearing the same issues voiced and yet still return to our target-based spreadsheets.

And, secondly, to our collective shame, fixing these issues is not rocket science. Nor will implementing a new, whizzy CRM system solve it. It demands that we pay close attention to the maligned “soft”, human side to our sector. The ‘why’ that sits atop the data gives you, the charity, a richer picture of how people really feel and behave.

We may see ourselves as a sector, as an industry even. But we do not exist for commercial gain. People do not have to support us. There is plenty else they could spend their spare cash on.

Giving is a philanthropic act that people choose to do because they believe in what you believe in; you stand for something that they feel needs supporting. A cause that chimes with how they see the world and how they see themselves. The shared values they try to uphold or want you to uphold on their behalf.

From a Twitter like through to a pledged legacy sum, supporting a charity is an act of generosity. Having people on our side is a privilege. It is to be respected. It is a gesture to be grateful for and thanked for. The human touch is how you show you are truly listening to them.

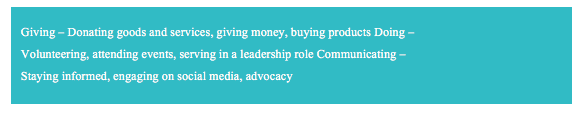

Ways donors engage (Association of Fundraising Professionals Information Exchange research into giving preferences)

Put supporters in the driving seat

The degree of control you offer people with the choices available, capture their preferences and respond accordingly is how you earn their trust. This directly affects their emotional association with you.

And, in turn, can lead to them taking the positive action that you seek in a way that is mutually beneficial, yet on their terms.

Once more, you can see how preferences, choices and donor control are just one piece of the puzzle. They are ‘gatekeeper’ moments; forks in the road.

This is about the bigger supporter journey within which you engage with people for the very first time, in the months or years while you are in touch with one another, and at the point – should the day come - they decide to call time on their relationship with you.

People-shaped fundraising

Earlier in this section, we concluded that choices and preferences offer charities an opportunity to a) listen, b) receive feedback and, consequently c) stay relevant.

It’s easy to talk the talk of ‘donor-centricity’, ‘supporter-centricity’ and the like. But the proof is in more than offering choice and control. It permeates through the very ethos of your charity; your culture. It requires shifting the focus from what the charity achieves to what the charity can help the donor achieve. You will have done your job best when you can get out of the way and simply connect a donor with your cause.

If you think it sounds cynical to focus on supporter self-interest, go and read the lifetime’s worth of direct marketing testing undertaken by the legendary direct marketer John Caples.

Over decades of rigorous statistical testing (detailed in his book Tested Advertising Methods) through live campaigns out in the real world, regardless of the product, three things always led to people modifying their behaviour and responding: news, self-interest and curiosity.

If you can inject your fundraising proposition with those three ingredients, you will be framing your ‘ask’ as less of an ask and, instead, as something far more positive: an opportunity for the donor to participate in.

Conveying that – not asking ‘Will you give money? but ‘Will you join us in our work?’ is the path to meaningful long-term relationships that are as good for your Excel spreadsheets’ Lifetime Value figures as they are for the donor’s soul.

And that proposition – combined with the ease of completing the action – needs to filter all the way down, right to how you frame choices, preferences and control to your audiences.

But why bother?

Why go to the trouble of giving donors greater control over how they interact with you? Why have a concern for every touchpoint, every interaction along the way from first to last? Why be in it for the long haul, for the whole journey?

Sure, thus far we’ve made the ‘soft’ case, rigorously backed up by scientific findings. But for the cynics, what about the ‘hard’ benefits? Let’s refer back to Rogare’s study:

And getting a positive donor satisfaction metric is probably on the target list of every head of fundraising in the land.

But as Matt Watkinson wisely cautions in his book Great Customer Experiences:

“More choice and more decision- making power does not necessarily result in a greater feeling of control. We should aim to give customers control where it is most effective in improving the experience.”

So what about the money? Is it worth all that effort? Research conducted by McKinsey and Company (management consultants for business) definitely proves it is. They’ve found commercial organisations that focus on the entire customer journey perform dramatically better than those who do not. They saw 10-15 per cent greater revenue growth, 20 per cent greater customer satisfaction and 20-30 per cent more engaged employees.

Then there’s the travel company Thomas Cook, who with their agency CreatorMail, won the Direct Marketing Association’s gold award for their data-driven approach to communications:

“As a result we are able to better understand the needs of our subscriber base and are now seeing our highest engagement rates to date because we’re sending more relevant communications.”

Later in the project, you’ll read about a 30 years young fundraising success story of donor-led choices, preferences and control in action.

But they didn’t do it because of the coffers. They did it because they cared about how their donors felt. They wanted a relationship, not a transaction. And true goodwill cannot be captured through LTV analysis, however useful those figures may be to you.

Or to quote Albert Einstein, a man hardly unfamiliar with the importance of scientific rigour:

“Not everything that counts can be counted.”