Forcing or forging a relationship? Part 2: what makes a relationship?

- Written by

- Charlie Hulme

- Added

- November 05, 2014

Step into any Pret A Manger, Pizza Express or Starbucks and you know exactly what to expect. You’re comfortable, you’re orientated. Everything’s where you think it’s going to be; you’re familiar with the product and service quality. You’ll never think of yourself as having a ‘relationship’ with these brands, yet there is a connection. In a world full of choice they are the default setting for so many of us when we want a sandwich, a pizza or a coffee.

Who are our defaults when we want to right a wrong, find a cure, or save a life?

Ask 100 people walking out of Starbucks what Starbucks does and you’ll get a very consistent answer. Were you to apply the same question to 100 donors sitting on your house file would you get the same consistency? You’re not alone; I’ve asked countless fundraisers the same question and not one of them could answer ‘yes’ either.

If Pret A Manager, Pizza Express or Starbucks were losing even half the amount of customers as we are donors they’d go out of business.

So what are they doing that we aren’t?

Forging a functional connection with their customers. In relationship theory this is defined as delivering a reliable and consistent experience. It is the first of two steps we need to take if we’re to create committed relationships.

If we’ve recruited someone with a message about saving a child’s life by buying a malaria net why would we try to upgrade them by talking about our work with orphans of HIV/Aids, then give them a ‘thank-you’ message for their help fighting tax-dodging corporations? Is it any wonder the poor donor’s confused where her £3 went? Is it any wonder so many of them leave?

Our inability to forge a functional connection is the reason over one-third of people who stop donating don’t actually stop donating to the cause. They just stop donating to you and switch to another organisation that, to them, appears to do exactly the same thing.

If we can fix this we can move to the second step of a committed relationship; personal connection. This is exactly what it sounds like. Do our donors know that we want to hear from them; that what they think and say matters to us, or are they just another name on a spreadsheet? Is there a sense of reciprocity? Are we speaking with them or at them?

Are we listening to them?

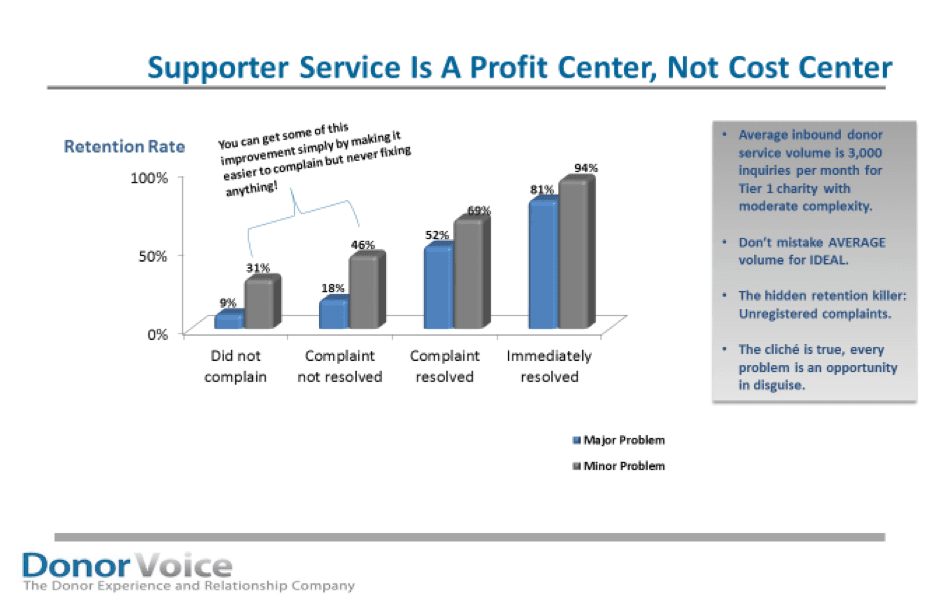

All relationships have their disagreements. The successful ones don’t try to avoid disagreements, they work through them together. So why do so many of us bury our donor or supporter services contact details in an obscure corner of our website, or list them in tiny print in our letters and magazines? One of the easiest, cheapest and most effective ways to achieve an enormous uplift in retention is simply by making yourself more readily available when donors want to complain. Take a look at the remarkable findings on this graph:

Retention for those with minor problems, i.e. ‘you spelt my name wrong’ is up 31 per cent for people who didn’t even complain but knew they could. Retention where they did complain and nothing happened, they didn’t receive any response at all, still goes up an incredible 46 per cent. Those who had a major problem and received a reply immediately is up 81 per cent and almost 100 per cent if the complaint was minor.

This is a quick win you could adapt today and if nothing else about your programme changed you could still expect to see a serious lift in performance, value and retention.

And then there’s all that money we spend trying to drive traffic to our websites. Why are we not making ourselves available to interact with people in real time, when they try and communicate with us, instead of only deigning to speak to them when the ask calendar tells us to?

At a deeper level there’s the question of a supporter’s moral identity.

How can we help them to be the person they want to be an, or, be seen to be? The two-stage model for donation decision making, which is tied to the ‘warm glow’ theory, shows the decision is largely about how it makes the donor feel. It is only secondarily about empathy for the recipient; the impact of the gift is barely on the radar except to reinforce making the donor feel good about her decision.

All of these, delivered consistently over time, are components of the personal connection that’s necessary if someone is to form the firm intention of standing beside you.

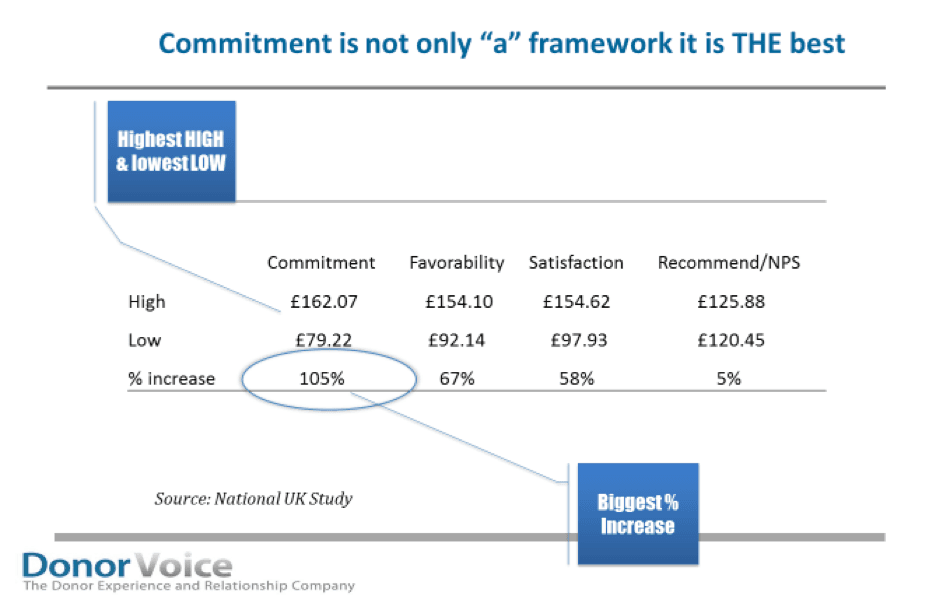

If we’ve built a functional and personal connection we have the bedrock of commitment. As we saw last time our current loyalty measurements are incomplete. Transactional data can only tell us what someone did, it can’t tell us what they’ll do. But by appending attitudinal data we are working with a forward looking, truly predictive framework.

The results are nothing short of stunning.

The following image, taken from a study of 50 UK charities, shows the massive percentage difference in lifetime value between low and high commitment donors.

Every one of those charities had high and low commitment donors sitting on their house file. And so do you. But, like you, they had no way to identify them. There is no good proxy sitting on our CRM systems that can ever tell us who is who. So time money and effort are wasted communicating with low committed people as though they were highly committed. And time, money and effort aren’t being spent on people with incredibly high commitment because we don’t know who they are.

Identifying who is who takes just nine simple questions that we’ll look at next time.

© Charlie Hulme 2014