Thinking of investing in segmentation? Be careful of these common and costly mistakes

- Written by

- Charlie Hulme

- Added

- November 09, 2017

In this first of two articles focusing on current fundraising practices, Charlie Hulme highlights five mistakes charities often make when investing in segmentation. Check in next week for part two, which provides insight into how you can transform your good intentions into a great supporter experience.

Fundraising has never been easy, but it’s never been this hard. So, in an effort to fix the acquisition and retention problem the sector's looking for new, or better ways to profile and segment prospects and supporters. But (with a handful of exceptions that I’ll share in the next post) no one has been successful.

The mindset is 100 per cent correct, but the methodology isn’t. So it’s worth looking at where so much profiling and segmentation goes wrong.

First mistake

The first misstep is usually some kind of supporter survey and, or, focus group. Behavioural science has repeatedly shown people can’t reliably answer these questions, yet for some reason we keep asking them.

It’s not that people lie on purpose, but because they fail to predict their future behaviour. Maybe the nature of the question is such that it can’t be answered in a reliable way, e.g. We carry out a range of activities to help [insert cause here], which would you like to hear more about? What reasons might stop you supporting a charity? Will you vote for Brexit, Trump, Merkel, Macron, etc? We want these answers, but we’ll never get them with these questions.

Second mistake

There is always some set of variables used to create segments. Either making it up as you go along, or a statistical grouping method. (The latter leads to a false sense of confidence.) The question that really matters is what variables get used. Why?

Whatever variables are used to create segments you will, by definition, see differences on those exact same variables when profiling. This is circular and tautological, but it is important because profiling of the segments, on the very variables used to create the segments, is what is used to feel confident about the segments being different.

If you have more data on your CRM, and you add it to your segments, you will see even more differences. The more data you use to describe, the more different they’ll look. These differences are as inevitable as they are irrelevant.

Third mistake

When giving behaviour variables are used, in whole or part, to create segments you’ve reduced your segmentation into a selection tool. In other words, it describes what they did, not why they did/will do it). Why?

Because giving behaviour is being used to explain giving behaviour! It is all effect, zero cause.

This is no different than regular RFV selection since the behaviour part drowns out any other variables. But those other variables (e.g. attitudes about your cause and wanting to help those in need) will make it look like it is something different, something tied to motivation, etc. It isn’t.

Fourth mistake

The reason behaviour variables get thrown into the mix is that attitudinal segmentation, more often than not, shows little bearing on behaviours. Why?

Because there was no theoretical basis for the attitudes used to create the segments. It just intuitively feels right to ask a series of global questions on how people feel (e.g. about your cause and supporting charities, etc) and then grouping based on the responses.

When you do this you merely wind up finding a number of segments with varying degrees of feeling on the battery of statements. This is neither interesting nor useful.

Fifth mistake

When the descriptive profiling is done on these attitude-only segments there is often little behaviour difference. So, some of those behaviours are thrown into the set of variables used to create the segments. And there you have it: instant ‘differences’ on behaviours you care about across your segmentation. But in reality, it’s just a weak form of RFV selection.

Many use demographics along with attitudes to ensure differences in the segments (to fit some preconceived, totally false notion that demographics matter). Adding age to the attitude variables will, by definition, create segments that think a bit differently (on random but alluring, irrelevant information) and that are different average ages. But so would adding star sign, height, or hair colour.

Result?

This approach always yields an enormous number of supposedly ‘strategic’ segments. I’ve seen them range from seven to 30+ plus segments. If they were real (which by virtue of how they were created is impossible) they’d be impossible to deliver on.

All told it’s an enormously costly effort to produce segments that put the ‘less’ in useless.

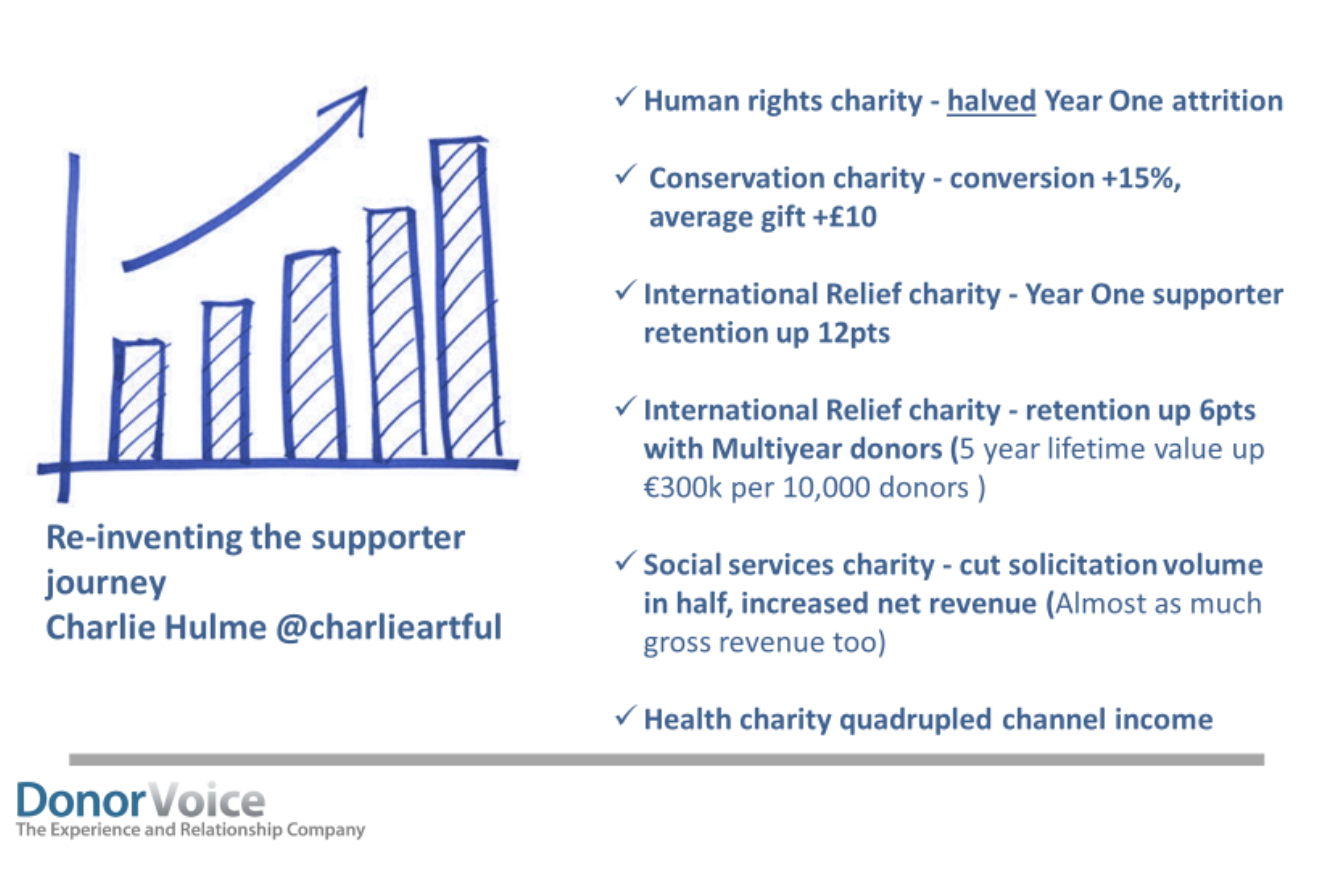

Again, the mindset of re-segmenting based on a deeper understanding of supporters is 100 per cent right. But it’s not hard to see this popular methodology is dangerously wrong. In the next article, I’ll share exactly how you should segment and how it led to results like these.