Forcing or forging a relationship? Part 4: how to manage a relationship

- Written by

- Charlie Hulme

- Added

- April 15, 2015

Even if you knew exactly who your most committed donors were, would you know what to do in order to keep them that way? In part three of this series we saw exactly how to answer the former question. But that information does nothing to answer the latter.

Just think how much time, energy and money we’re spending to deliver ‘supporter’ experiences across the breadth of our organisations. Each experience is creating an impression, which is forming an attitude, which in turn forms someone’s decision to stay or go. Yet we have no way of knowing how each contributes to the collective whole in the mind of our ‘supporter’.

No amount of data segmentation, transactional information, or appended lifestyle data can specifically answer the only question that counts when planning strategy: which, of all the things we're saying and doing, truly matters to our donors and which doesn't? Nor is there any point 'innovating', being 'donor-centric', or reaching for any other buzz word. Without a solid, empirically donor-led baseline it's all just guesswork. The best we can do is stumble in the dark using technique as our guide.

Fortunes are spent on 'supporter journeys' without our having the least clue as to where that 'supporter' wants to go. A journey where only one party knows where they're going is abduction! Is it any wonder so many leave?

A 'supporter's' decision to stay or go is very far from being determined solely by the actions of the fundraising department. As Roger Craver's study, Retention Fundraising, has proved, at best only 20 per cent of a 'supporter's' decision to stay or go can be attributed to the actions of the fundraising team. The other 80 per cent sits across the totality of experiences your organisation is creating. Which makes the idea of a retention officer sitting in yet another silo absurd.

Retention isn't something you do it's everything you do.

So unless you know how one experience affects another you'll never know why someone chose to stay or go.

Take your magazine for example. I'm sure like most charities you have one. I'm sure like most charities your magazine makes a financial ask. And I'm sure like most charities your magazine makes a financial loss. In the eyes of your CFO that magazine is a red number, an expense that needs to be cut. Yet many in the fundraising department believe the magazine adds value; that people appreciate it and that, in turn, it influences future donations. We just can't be sure.

One very well-known fundraising consultant told me his answer to this conundrum: he reduced the cost, and quality, of the magazine. So, if the magazine had been a good experience he's now made it a crappy one. If it was already a crappy one it's now even crappier. He'll probably win an award.

How different would your strategy look if you knew for sure how much each individual experience mattered and which didn't?

If you knew for sure how much of each donation was going to which specific activity, area, or experience? How much money would you save? How much more would you raise? These aren't fanciful questions; they can be answered in precise detail by applying commitment modelling.

As we've already seen in the previous articles everything we deliver has an influence on a donor's functional and personal connection with us. This in turn helps or harms their commitment to us. In part three I discussed how to measure that, now you can take it a step further and actually manage it.

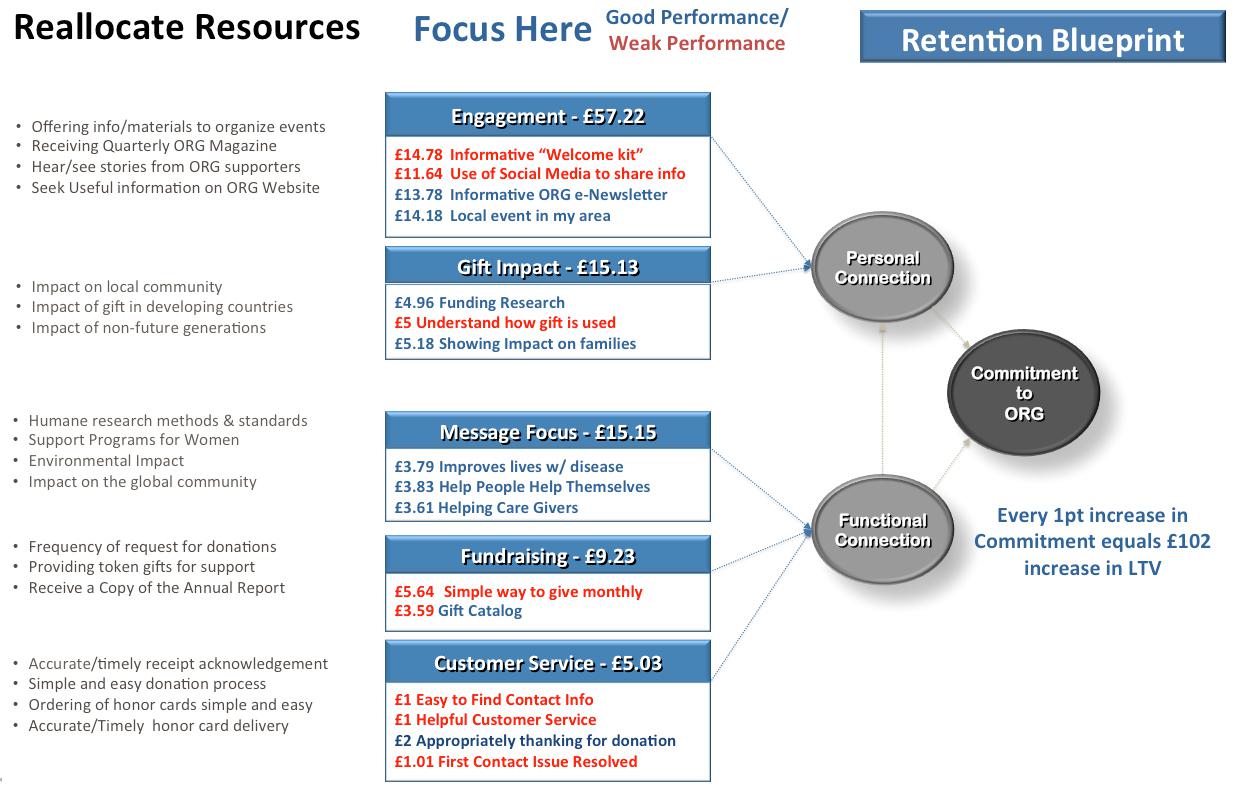

The image below is a retention blueprint of a well-known charity. Every 'experience' they create is listed and has a specific value attributed to it. This has been derived by surveying* a cross representative sample of donors and filtering every 'experience' (i.e. fundraising, brand, communications, donor service, etc) through the lens of our donor commitment model.

Commitment modelling uniquely combines attitudinal data with transactional, giving you a cause and effect model of how one directly has an impact on the other.

On the right-hand side you see three circles: one each for functional connection and personal connection and one for the commitment they are causing. In the middle you see five boxes, these represent, broadly, experiences the charity delivers that are causing either functional or personal connection, i.e. message focus, donor service etc.

The financial value attached to each is the proportion of lifetime value per commitment point that is being donated to each area, in this case £102. Within the boxes those values are broken down still further to the point that each individual activity or experience has a specific financial value. So here for example £4.96 of the £102 is going to 'funding research'.

For the first time ever it is possible to take a bird's eye view of everything you create and accurately determine the specific financial value of each experience.

Experiences listed in the boxes in the middle column represent the totality of a 'supporters' relationship with you. These are the things you are doing, today, that matter to them. Think of it as an itemised bill for the job they are paying you to do.

Items listed in red mean the experience is important but is broken and needs fixing. This means you now have empirical evidence on which to make donor-led change. If, for example, an operational decision is made it's done because you know that's what will drive commitment in your donors. If you decide to scale down telephone fundraising and scale up your e-appeals, it isn't done because someone high up internally prefers one to the other, but because your donors do.

Items listed in blue mean the experience is important and working well. For example in this case donors like the e-newsletter. The question then becomes how can we scale this? Let's say the e-newsletter was being sent monthly could we test sending it weekly?

Now take a look at the column on the left-hand side. This is everything else this organisation spends time, effort and money on that doesn't matter at all to donors. None of them are inherently bad or wrong, they simply do not matter one way or the other to a donor's commitment to that charity. The time effort and money spent here trying to make donors loyal is wasted and sometimes directly detrimental. This charity would do much better reallocating resources to areas they now know matter. In this case their magazine was a bad experience and was subsequently ditched, immediately saving them over £150,000.

This is not a commentary on whether magazines are good or bad. I've seen as many cases where the magazine was vital as where it should be dropped. The point is do you know which category yours falls into? If you don't, how can you be sure of anything you're using to try and forge a relationship? If your year-on-year retention rate is static or dipping then, no matter how much you intend forging a relationship, all you're doing is forcing one.

This is pure, scientific, relationship fundraising and it doesn't require any additional effort or spend.

In fact it requires less. This is addition by subtraction.

What you see in the retention blueprint is a strategic brief, designed by donors. If we deliver on this, to the exclusion of everything else that doesn't matter, we have all the elements that go into creating a committed relationship. All the guesswork has gone! Unlike recency, frequency, value modelling which can only ever tell you what happened, this model tells you why. It is pure cause and effect. The more we deliver what they want, to the exclusion of what they don't, the more we're feeding their commitment. As their commitment increases so does their value, in this case to the tune of £102 per commitment point. This applies equally whether someone's score goes from two to three or from seven to eight.

This represents enormous value waiting to be unlocked on your house file today.

Next time well look at how to take this a step further still, to guarantee you know exactly what your fundraising message should be and how you can best deliver it.

© Charlie Hulme 2014

* No sector has been more badly burned by poor survey work than ours. But the fact that most surveys carried out in our sector are lousy says more about the methodology than the process itself. Without wishing this footnote to turn into a book, let me just state that if you ask a silly question – i.e. do you agree that charity CEOs are paid too much, or are you happy that we ask you to increase your gift, etc? – you'll get a silly answer. There are however proxy questions that can be used to determine, with great accuracy, the thoughts/ feelings/ attitudes we all have.