How I wrote it: Alan Sharpe’s War Child fundraising letter.

In this, the sixth of a series of interviews with leading fundraising writers, Alan Sharpe talks with Fergal Byrne about a fundraising letter written for Canadian charity War Child in 2011. During this conversation, Alan reveals the thinking that went into his letter and what really matters in making a letter a success.

- Written by

- Fergal Byrne

- & Alan Sharpe

- Added

- February 10, 2012

Here you will learn

- The two most important words in fundraising.

- The power of premiums.

- How to keep the reader reading.

- The cycle all good fundraising letters must go through.

- The value of monthly giving.

Background

War Child is a Canadian charity that protects children living in some of the world’s most dangerous countries. Their mission is to empower children and young people to flourish within their communities and overcome the challenges of living with, and recovering from, conflict. The charity approached Harvey McKinnon Associates (HMA) in 2011 to help them acquire donors through the mail and to grow their database. At that time, War Child did not have a history of acquiring donors through the mail.

Alan explains, ‘One of the reasons we started working with this client was that we felt an immediate affinity with what they do; we believe 100 per cent in their cause. Dr Samantha Nutt, the founder of War Child, is highly respected and admired in Canada’s medical and NGO environments.’

Alan felt pretty confident that War Child would be able to raise money through direct mail cost effectively. ‘We don’t take on projects with clients if we don’t think we can raise money for them through the mail. Sometimes, for a variety of reasons, it is better to accept that some organisations won’t be able to raise money this way and to tell them. We were confident that War Child was a cause that would resonate with Canadians and that they would be successful.’

HMA wanted to help War Child find out three things. Could they acquire donors through direct mail cost effectively? What were the best lists they could use to acquire those donors? Should they use a premium to acquire as many donors as possible at the lowest cost per piece, or per donor?

The results

The mailing was a great success. The average response rate for all the lists was one per cent and the package with the premium brought in twice as many donors as the one without. ‘Of the mailing lists that we tested, the best performing list had a response rate of 7.8 per cent, which is absolutely amazing for donor acquisition, For two of the lists, War Child were able to make money on acquisition and for others they had to spend money to acquire a donor.’

The two biggest challenges

At the outset, Alan identified two main challenges for the campaign to succeed. The first was to tell the children’s stories without seeming to exploit them. ‘War Child, like many other similar organisations, are very careful about how they portray the people they help. They don’t want to patronise them, to make them appear to be helpless and without the power to improve their lot in life. This can lead to the paternalistic attitude that only we in the West can help those poor starving children in Africa.’

Alan adds, ‘You have to be very careful because this can become increasingly shrill. If your last image was of a child that had been bayoneted or blown up and the response rate is declining, the temptation is to up the visceral level of the imagery and the stories, make them more outrageous and even more graphic.’

The second challenge was that they were writing to people who were on other people’s lists. ‘We were confident that they had probably heard of War Child and maybe knew a little bit about them. But they were not as familiar with War Child as they would be with Doctors Without Borders, Oxfam, or Amnesty. We had to communicate a powerful story at the same time as telling people enough about the organisation to help them to make a decision about giving a donation.’

All this suggested to Alan that they would need a letter that was longer than two pages, which presents its own set of challenges. ‘It has to hold the attention of the donor so it has be emotional, tell a story and also present some facts about the charity – who they are, when they started, what they do, who they help... You can’t just manipulate people’s emotions. Your letter has to be emotional but also factual to appeal to the heart and to the head.’

Who writes the letter?

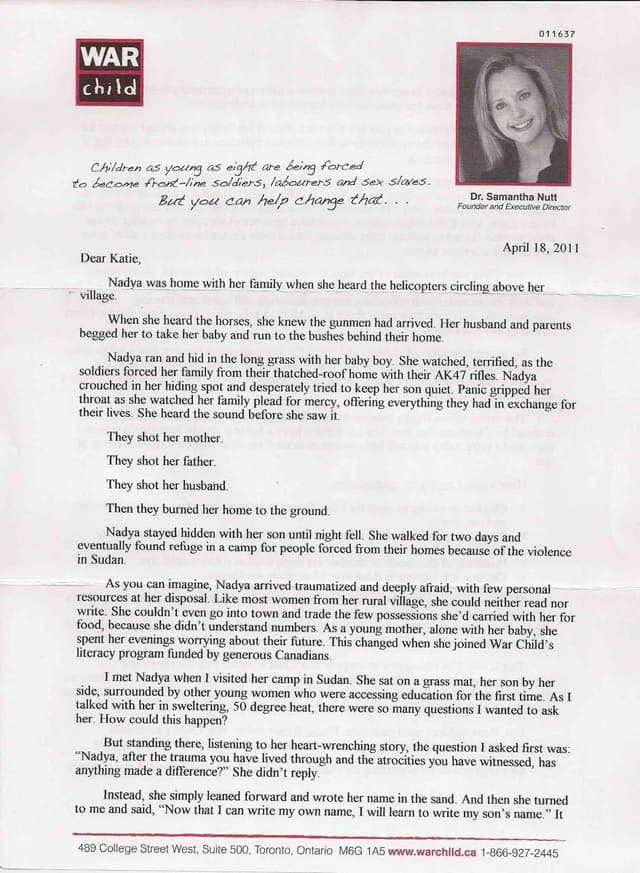

This can have a big impact on the success of the letter. From the outset, Alan felt confident that Dr Samantha Nutt was the best signatory. ‘We just knew that it had to be Samantha because she started War Child. She’s a paediatrician and she actually goes into the field and helps these children. As we were writing to strangers, the letter needed a signatory who had the highest public profile and could speak with the most moral authority on the topic.

‘An alternative, of course, would have been to tell Nadya’s story in her words. A story is always strong if it’s told in the first person by somebody who has been helped by an organisation. Of course, we couldn’t do that without her permission, but she’s in a refugee camp somewhere and we weren’t able to track her down.’

Getting the reader’s attention

Dear Katie,

A lot of acquisition letters just say ‘dear friend’. Alan says, ‘We believe in calling people by their first name rather than dear friend. It costs more to personalise, so it’s worth testing because it might be more cost effective just to have a dear friend letter.’

Different writers approach writing in different ways. Some like to start with the reply card, for example, others with the postscript, others like to start at the beginning. Alan focuses on the opening line. ‘ I can’t write a letter like this until I’ve written that. Sometimes I’ll sit for hours before I have a good one, but once I have it, generally, I can write the letter from there.’

Nadya was home with her family when she heard the helicopters circling above her village.

Alan believes the opening line has to stop the reader in her tracks, ‘That’s the hardest thing to do. You have to give enough information so that she wants to continue reading, but not so much that she thinks, “Oh I get it, this is an appeal letter and it’s going to ask me for money.” It has to have some human drama in it wherever possible.

‘The quickest way to grab and keep a donor’s attention is to start telling a story. So I started this letter with drama. I packed as much suspense, terror and angst into the opening as I could so that readers would feel compelled to finish the letter.

‘It shouldn’t do it just with shock value, because you could stop people in their tracks by using a swear word or by announcing free beer: it is possible to grab people’s attention in an irrelevant way or in a way that kind of manipulates them. The opening line has to be compelling, plausible and it has to be on-brand with who the organisation is and the kind of voice that they have.’

He continues this process as the readers get into the first, second or third paragraphs of the letter, ‘I am always asking myself what can I say that will get the donor to continue reading? What questions would she have pretty quickly as she's reading the letter?’

One key question needs to be answered promptly: ‘Who are you and why are you writing to me? Then there are others, ‘What do you want me to do? Why should I support your cause? What difference will my donation make?’

Alan says, ‘I try and anticipate all these questions and don’t necessarily address them in a certain order, just when it seems naturally appropriate. Nadya’s story is so powerful. When I interviewed Samantha Nutt, she described how they met in a refugee camp and Nadya told her story. I recorded the conversation, transcribed it and then I made that the opening. I knew this would have an impact.’

When writing a letter like this, Alan believes that it is essential to present the cause or the need upfront. ‘You have to show that there’s this terrible tragedy, this injustice, in the world, that something is going on that demands the donor’s attention and action. Then somehow you have to move smoothly from that need to how the donor can help meet that need or solve that problem.’

Identifying the cause: what does War Child actually do?

I met Nadya when I visited her camp in the Sudan.

‘The letter starts off talking about Nadya, then moves swiftly to introduce Samantha so that people understand who this letter is from and why they should carry on reading. The voice changes and it’s Samantha talking.’

I work for a charity called War Child… As you can probably tell from our name War Child helps children whose families have been torn apart by conflict.

Many charities find it hard to describe in simple terms what they do – often because they do so many good things that it’s difficult to narrow them down to one or two paragraphs.

‘When you speak to a charity, they’ll tell you that they do famine relief, dig latrines, feed the poor, inoculate the sick, help with blindness, dig wells, do literacy training, but you can’t tell the donor everything that an organisation does. Our challenge was that we were writing to people who maybe didn’t know a great deal about War Child, but we didn’t want to write a letter that communicated all that they do.

‘We had to describe their work in the simplest, yet most convincing way so that donors could see quickly that there is a need and there is an organisation that can meet that need with the donor’s help. We knew that with a name like War Child it was very important that the letter talked about child soldiers, as we figured that’s what most people would think of when they thought of War Child. We mentioned the work they do in the refugee camps a little, but not at the beginning because we wanted to start off strong by describing that predicament.’

About War Child

War Child doesn’t just help child soldiers it does a lot to help children in areas that are involved in conflict. They do go to countries where children serve in militias and help rescue children who have served in the army. They also help children who are victims of conflict, children who have been involved in civil wars, children who were forced to leave their homes and are now living in refugee camps because of conflict. And they don’t just work on the frontline rescuing children from service in the army. They also help children who are in the camps, they help them with literacy and with hygiene and with job skills training.

How can the donor help?

Here’s why I need your support now…

Your support will change lives.

Alan says that wherever possible he tries to talk in terms of how the donor can help deal with the problem and is always completely truthful. ‘We have to present the facts as they are and not coat them in sugar. If children as young as eight are being forced to become frontline soldiers, labourers, or sex slaves, if those are the people that War Child helps, then we need to say that so the reader really understands that this is awful and that she should do something.’

The ask

That’s why I am asking you to support War Child’s vision.

Alan does not have any fixed rules about asking. ‘Some people arbitrarily say that there should be an ask on the first page, there at the bottom. I’m not as rigid as that. I say that you have to ask at the right time. A man that wants a woman to marry him won’t ask for her hand in marriage on the first date. He has to warm her to the idea before he proposes.’

Alan argues that it is essential to get the donor’s interest before you ask for a donation. ‘You have to get the reader’s interest, then move her emotionally, then explain a few things rationally for why she should help – and then ask for the gift. You certainly want to ask somewhere on page one, or if this is a four-page letter you certainly want to do it by page two. If you leave it too late people will start wondering what it’s about and what you want them to do.’

This letter asks the reader to support War Child’s vision. Alan believes if you can get people to support the vision of the appeal then it’s easier for them to take action and to donate. Indeed, Professor Adrian Sargeant has discovered that donor loyalty depends on just seven things – one of which is that your donors share your beliefs ((Tiny Essentials of Donor Loyalty, The White Lion Press, UK, 2010).

‘The vision is obviously the highest goal that you’re asking a donor to aspire to. Ending breast cancer in our lifetime, that’s a vision,’ says Alan. ‘Ending acute poverty, that's a vision. A world where children don’t know war is a vision. You’re trying to get the donor to agree that it’s a good thing. Rather than asking for a donation to help Nadya’s daughter or son learn to read in a refugee camp in Sudan you’re asking if the donor agrees that we should have a world without war for children. You hope that she’ll say, “Yes I do, I support your vision.” Basically you’re taking the whole case for support for the organisation and distilling it into just a phrase.’

The right use of underlining and bold

In general, Alan tries to avoid underlining and bold as he feels that that they’ve been overdone. If you underline everything, then you underline nothing. ‘My preference is to have underlining maybe once or twice on a page, if at all. I’m not totally against it, but I prefer not to use it and I shy away from exclamation marks as well, anything that sounds shrill.’

But Alan believes that it is helpful to have the ask on a line of its own that’s underlined as it will attract those readers who are just scanning the letter. ‘The top of the page is underlined: that’s why I'm writing to you now. Then further on, I need your support now. On the next page, your support will change lives. Two thirds down: so I ask will you donate today? It’s obvious that there’s a need, that’s why she’s writing, it’s urgent and you can help now.’

How to keep people reading

But these children need your help.

So I urge you to do something life changing.

One of the greatest challenges a writer faces is to keep the reader reading. Alan believes that the beginnings of paragraphs are important. ‘I write the opening couple of words of every paragraph in such a way that they have a momentum that will make the donor feel that she has to keep reading – words like but, and, so. I prefer to use these rather than simply underlining things and making them bold, or putting fake handwriting in the margin.’

Wherever possible Alan tries to end a page in the middle of a paragraph as this helps compel the reader to continue reading. ‘You'll notice that the first page doesn’t end with a complete sentence, it ends with “it” and you have to turn over. The second page does end with a full stop, but the third finishes right in the middle of a paragraph. We always try to do this so that a reader cannot get to the end of the page and think, “I’ll just pause here.” She has to actually finish the thought and so has to turn it over.’

The two most important words in fundraising

A big mistake with nonprofits, particularly relief and development organisations, is they have ‘NGO-speak’, which can alienate potential donors. ‘Very often charities use their own jargon. They talk about IDPs for example. (Internally displaced people have had to flee their home, but haven’t crossed a national border so are not recognised as refugees.) This kind of bureaucratic, government‑type language – the kind of language that you’d use in a proposal to a government body for funding – isn’t the language that an individual uses and can be a complete turn-off for a potential donor.

‘We should be talking in ordinary everyday language when we talk about the people we serve. This letter aims to reach people who care about children, care about the children in developing countries, care about conflict and making the world a better place through World Child. As Tom Ahern, fundraising consultant and writer in the USA, says: “People don’t give to your organisation, they give through your organisation to change the world.”

‘The letter shouldn’t talk about War Child this, War Child that, we’re the greatest, we’ve been around 10 years. It’s important that the letter puts the donor first and says, you can make a difference, you can help the children, your gift will make a difference today… A letter like this has to have “you” in it a lot. Every now and then it obviously has to say us and we, but they should be kept to a minimum. The most important words in fundraising are you and thank you.’

Although Alan admits he doesn’t always do the chickenpox test, he recommends it highly. ‘It's very helpful when you've finished your letter to take out a red pen and circle every time you say we, us, our, or the name of the charity. If your letter looks like it has chickenpox then you need to change it. So instead of saying, for example, we help children of conflict you should say, your donation helps children of conflict, or your donation to War Child helps children of conflict. It’s almost always possible to put the donor into the sentence.’

Using strong language

Your support WILL change lives.

Wherever possible you should put the donor in the position of actually making change. ‘So we try and avoid the words can, may, might, will and simply say, your gift feeds the poor, your gift buys a meal, or feeds a homeless person. Saying your support will change lives is a strong sentence. On reflection, it would be even stronger to say: your support changes lives.

The cyclical structure of successful fundraising letters

There are many different approaches to structuring a fundraising letter. Alan believes that there are basically three things you want to do in all fundraising letters. There’s a cycle: you present the need, then you show how the organisation meets the need and then you show how the donor meets the need by supporting the organisation. Then you repeat the cycle: you go back to the need and explain a little more about it and then a little more about how the organisation helps, then ask again for a gift.’

How will you spend my money?

I hope you appreciate that since our founding in 1999, more than 90 cents out of every dollar raised has gone directly to our charitable programs for children.

The question of how the money raised will be spent is something that is usually mentioned in acquisition mailings, less frequently in other kinds. But it is something that new donors care about it increasingly. ‘By definition an acquisition letter is being sent to strangers that have never given a gift to the organisation before,’ says Alan. ‘Nowadays we have to assume that donors want to know how their gift is going to make a difference and how efficient the organisation is going to be. It’s common practice with acquisition mailings in Canada and the USA that the charity will have a pie chart somewhere that shows what percentage of their donors’ money will go on admin, fundraising and programmes. More and more organisations want to see that chart showing at least 80 per cent expenditure, so 80 cents of the donor’s dollar will actually go to help children. Donors have been kind of brainwashed by the media that a high fundraising or administration cost is a bad thing. So organisations simply meet that head on by saying how the gifts they receive will make a difference.’

A second case: Samir

If you want to know if your gift to War Child, will make a difference, just ask Samir.

On page three of the letter we meet Samir. Alan explains that, ‘Samir is introduced here because we wanted to show the full circle of how War Child actually helps. War Child does rescue babies and children from conflict, but then they help them with literacy and job training so they can make a difference to their lives. So we moved easily into the story of this young man, Samir, to show how War Child helps children avoid getting involved in the armed militias.’

Monthly donors worth thousands of dollars

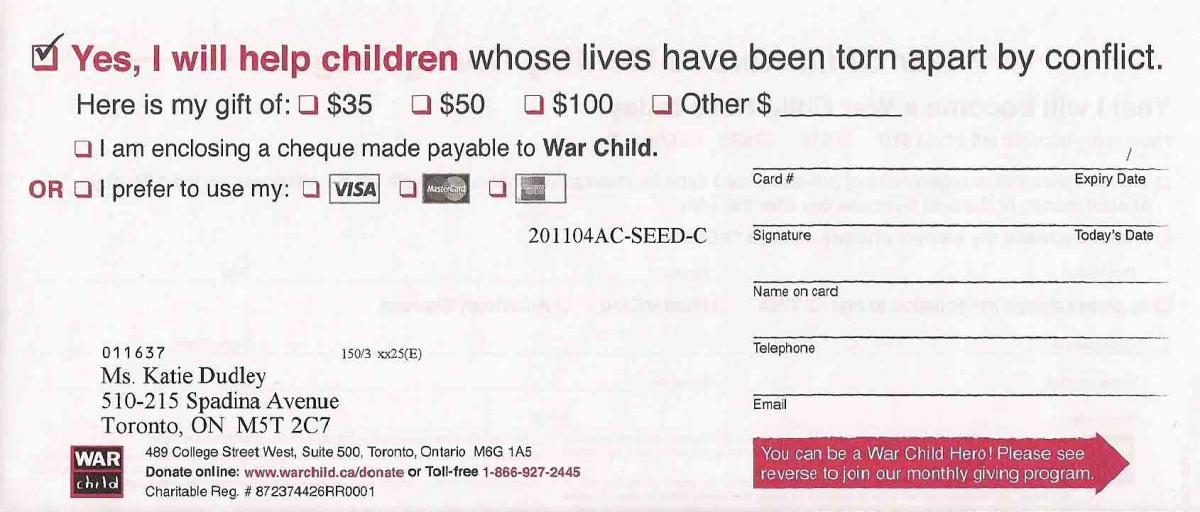

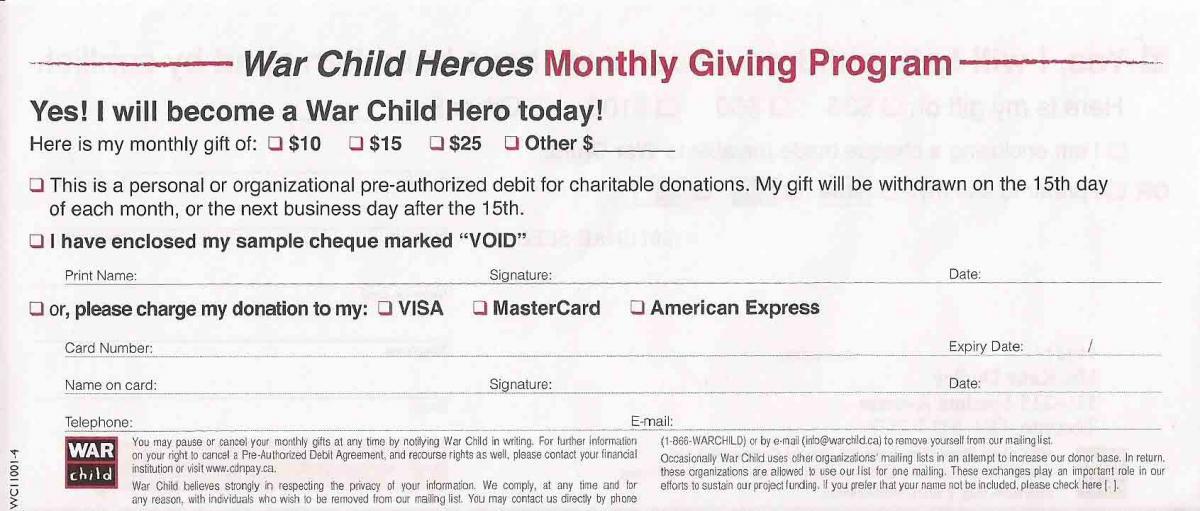

Please give now by making a single donation or consider becoming a War Child hero by joining our monthly program.

Alan is a strong believer in monthly giving and always asks donors to consider joining a monthly giving programme. ‘A typical monthly donor will give you $1,500 in her lifetime, so we’re big believers in converting people to monthly giving as soon as possible and we give them that option in the acquisition mailing.’

At the bottom right hand corner of the reply device donors are directed to information about becoming a War Child hero, which is on the reverse. ‘They can become a War Child hero with the monthly giving programme. The cost of entry is a lot smaller than the one-time gift on the other side of the page, that’s $35, a monthly gift starts at $10.

Silly postscripts

After 15 years of helping children traumatised by war…

Alan is not a big a fan of PSs – as he believes they are fake. But he does recognise that people read them. ‘Studies show that the PS is one of the first or maybe second things that people read and so I include it in fundraising letters. But I try to satisfy this annoyance I have that they are fake by at least putting something in the PS that is an afterthought. I try to write one that actually says something that is not in the letter, rather than simply reiterating the case for support, repeating the ask, giving the deadline or the call to action.’

The power of premiums

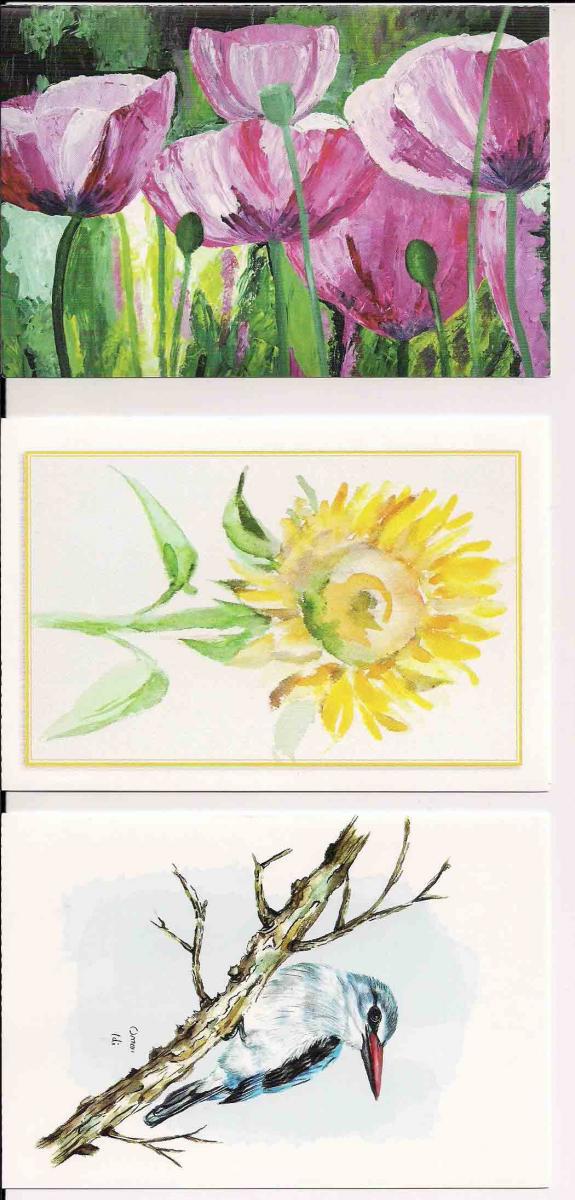

‘Including a premium in an acquisition mailing tends to pull a higher response rate and we wanted to test this with this letter. Some letters included the greetings cards and some didn’t. The people who received the greetings cards responded in twice as many numbers as the people who didn’t get them.’

However, Alan points out, ‘If you use a premium in acquisition you tend to get more donors, but they tend to give you a smaller average gift. Some donors get the greetings cards and think, “It’s nice of these people to give me this premium, it even has my name engraved on it.” So they give a token gift of $5 or $10, just to placate their conscience or guilt because they’re going to use the note cards or greetings cards.’

Alan suggests that this is something that every charity should watch. ‘The key is not to measure your short-term results and think, yes, we got twice as many donors with the premium, let’s keep mailing them The initial results of an acquisition mailing might tell you that the package with the premium brought in more donors. But you should look at those results five, six, or seven years later to measure the lifetime value of donors who were acquired with the premium and those that were acquired without it, to see which group gave you more.’

An affirmative reply device

Alan always tries to have an affirmative statement that’s written in the voice of the donor. ‘Rather than having a sentence that says give today we have an affirmative statement that they can tick in their mind and say, “Yes I will help children whose lives have been torn apart by conflict.” We repeat the case for support in one sentence wherever possible.’

Alan’s wants the card to be as simple as possible so that here there are just two tick boxes: I’m enclosing a cheque or I’m paying by credit card. ‘We give the donor as little to do as possible so that we can secure the gift – either I’m giving a one-time gift or I want to join the monthly giving programme.’

Choosing the premium

Alan says, ‘We chose cards that had an African look and sensibility. They included four cards because four usually out-pulls two. It’s better to have four than six because six makes the package too heavy and you end up paying first-class postage. We included a mix of landscape and portrait cards that would appeal both to men and women. We included flowers because we’ve discovered that flowers pull really well when it comes to greetings cards.’

Alan did not want the cards to have any War Child branding on them. ‘We wanted to make sure that people would actually use the cards without thinking that by sending them they would be taken as an ambassador for War Child. It’s a little too soon to be asking them to do that. If somebody’s been a supporter for 10 years of UNICEF, for example, they might be glad to send UNICEF labels. But we think that people are more likely to actually use the cards if they’re not branded with the organisation’s name.’

Alan also wanted to avoid branding because he knows that some people are hesitant about sending a greetings card that has a nonprofit logo on it because they think that the people receiving the card will think that they are cheapskates, sending a card that they got free from some charity. With these cards they wouldn’t appear to be a tightwad.’

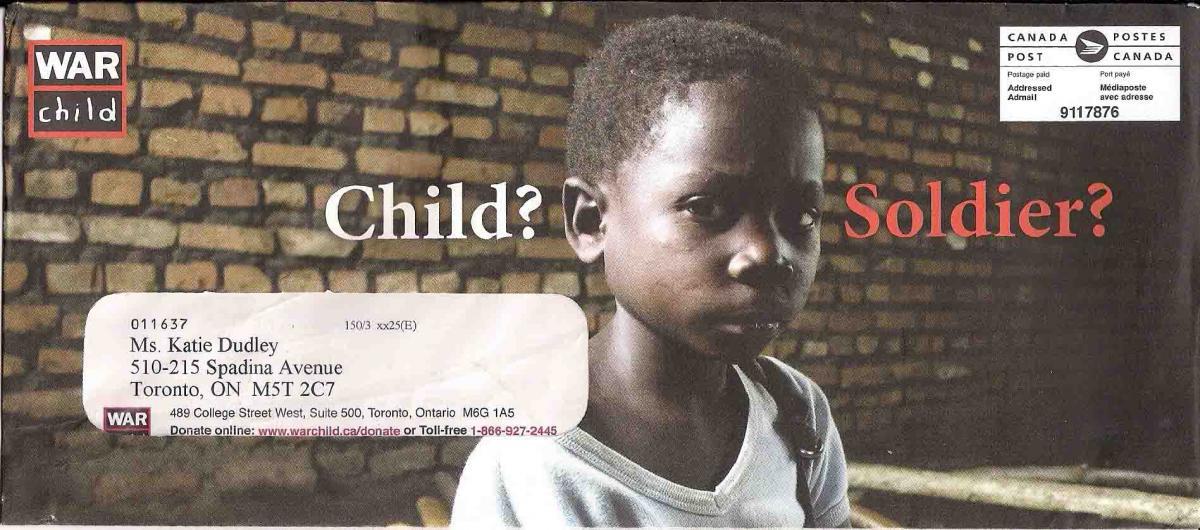

Grabbing the reader’s attention with the envelope: child or soldier?

Alan knew he wanted something graphic on the envelope that would really grab the reader’s attention, so decided to use the photograph of a child in Africa. ‘We just presented this question: is this a child or is this a soldier? We figured that, as we were communicating with a new audience that hadn’t heard from War Child before and might not know who they are, we should immediately communicate the idea of children and child soldiers in a forceful way.

‘The whole point of this outer envelope is the question: is this a child or is this a soldier? Because you can determine the outcome with a gift today. That’s why on the back of the envelope we took this popular phrase, a fighting chance, and struck out the word fighting.

Tracking the mail

The return envelope is coded-WC110001-4 in the bottom left-hand corner of the envelope, which allows them to track the results. ‘Some people will respond to a mailing like this by just mailing a cheque,’ says Alan. ‘They are effectively saying: “I don't want you to know who I am, I don’t want to use the reply device so I will just send the reply envelope.” The code means: War Child, year 11, first mailing and it went to the group that received the premium This is how you can track the results of this campaign even if all they do is send you cheque.”

Testing benchmarks

First of all, charities should expect to receive a response rate of around one per cent. It depends on the charity but typically the average gift should be somewhere between $20 and $30. They should be aiming for a net cost of acquisition. Whether or not it’s affordable is determined by the lifetime value of a typical donor. If they know how much a typical donor gives in her lifetime, they know how much they should spend to acquire that donor, but a lot of organisations don’t know that.