How I wrote it: the Make-A-Wish Foundation’s prospect letter

In the second of a series of interviews with leading fundraising writers, Harvey McKinnon talks with Fergal Byrne about a fundraising letter he wrote for the Make-A-Wish Foundation, Canada, in 2002. In this conversation Harvey tells how he wrote this letter and expands on his approach, paying special attention to the art and craft of writing and telling fundraising stories.

- Written by

- Fergal Byrne

- Added

- October 29, 2018

The challenge

‘I was asked to develop a direct mail prospect package for the Canadian Make-A-Wish Foundation,' Harvey explains. ‘This was the first time the Foundation was going to use a prospect package to acquire new donors. They intended to mail to untested lists with an untested package. The letter, of course, is the key to the success of any campaign. Ultimately my goal in writing any letter is to inspire the reader, to touch his or her heart, to make her want to become a participant in this good work we are talking about in our letter.’

What happened

The results were excellent. This donor acquisition package made a positive return on investment of $1.59 for each dollar spent and achieved an overall response rate in excess of two per cent.

The Make-A-Wish Foundation grants wishes to children who have life-threatening medical conditions. With some 200,000 wishes fulfilled globally every year, the Foundation has many stories to tell. Harvey was looking for a strong, powerful story about one of these children.

Harvey says, ‘Basically, there are two kinds of stories that can be told. In effect, the first kind of story says “as a result of the good work of the donors, the responders, a problem was solved. Moreover, there are other children like this who also need the donor (or a person like the donor) to help them overcome some obstacle”. The second story type deals with a scenario that says “we’ve got a serious problem and we need people like you to help us solve that problem”.

‘The Make-A-Wish Foundation has two kinds of core stories,’ says Harvey. ‘The most common of these involves a child who is dying. The child is not going to survive. So, the thinking becomes “let’s give this child a great wish-come-true before he or she dies”. Occasionally, very occasionally, we come across a story like this one, when the child who was expected to die survives. When the child’s father says “it was a miracle”, he totally believes it was a miracle,’ Harvey says. ‘That survival story alone is heartening to everyone, but particularly if the reader is a parent and grandparent.’

The power of a good story

View original image

View original image

Harvey states, ‘A good story has to have a number of qualities. First, it has to have emotion. Secondly, it needs to be real – we need to have something tangible happen. Stories have to come from a credible source – a mother talking about her child, someone who was homeless and who now has somewhere to live. Both of these scenarios are credible and understandable. Lastly, the notion that illustrates how the charity’s intervention makes the difference, thanks to a donor’s gift.’

Harvey believes that fundraising writers develop a sense that if the story is able to move them (the writer) emotionally, there’s a very good chance that story will also affect a lot of other people emotionally. ‘Carlie’s story is great – not because of any skill I may have as a writer, but simply because it is a great story.’

Capturing the emotion in the story

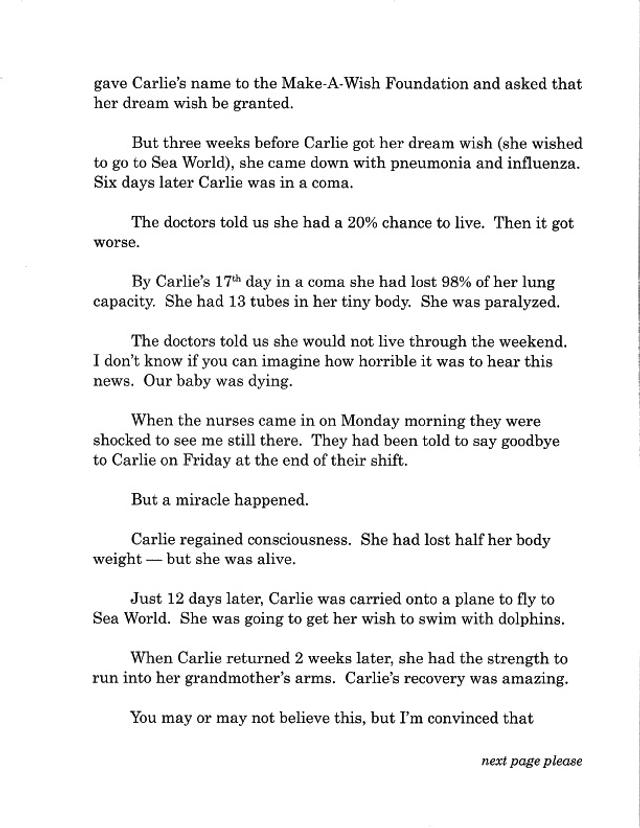

View original image

View original image

Most charities have a data bank of stories, but sometimes the writer has to do the research himself. That’s what happened with Carlie’s story. Harvey says he often approaches an interview a bit like a newspaper story, ‘The challenge is to get the interviewee to say what you want her or him to say in a way that will have a strong impact on the reader. The key to pulling out the emotion is to learn how people feel at different points in the story, to touch on their emotional experiences.’

Harvey says, ‘You could tell this story by simply relating the facts – it might be interesting but would not be moving. Carlie’s story is very emotional, especially as related by her father, a sensitive, caring man, who was speaking about his daughter. I’m not embarrassed to say that when he was telling me his story, I wept. I’m a parent so I know the fear every parent carries in his or her heart. And yet, even as I was choked up, I was thinking to myself that this would be a great fundraising story.’

However, Harvey emphasises that it is important to make sure the person in whose name the letter is being written understands how fundraising letters work. It is important to get his understanding and support for how the letter will be written.

‘I needed to explain to Carlie’s father that the style of writing would be very different from his normal speaking style. There are key elements in a fundraising letter that pretty much have to be present to make it successful. Carlie’s father had to feel comfortable with a style that might not sound like his voice. Normal people (even fundraisers!) don’t necessarily talk the way a fundraising letter is written.’

Pitfalls to avoid

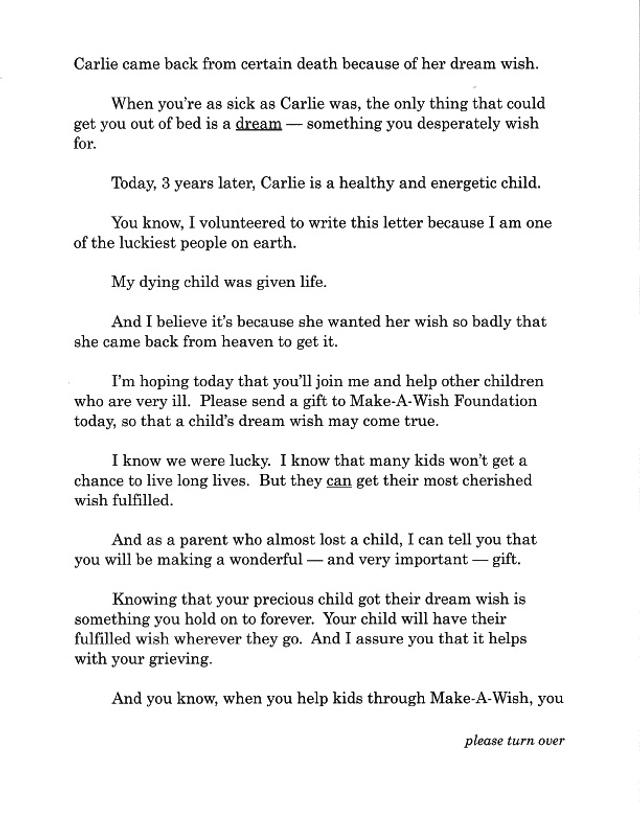

View original image

View original image

‘It’s not just about writing and capturing the story’ Harvey says. ‘Writers must be sensitive to all of the nuances in the situation. Sometimes a writer can have too much emotion and needs to be careful not to inject more than the storyteller is comfortable with. Some people believe too much emotion is exploitative of the person you’re trying to help and that can cause a backlash within the charity and its supporters.’

Harvey adds, ‘Writers need to be sensitive to the nuances or politics of a cause, for example, disability issues or when writing about people in a developing nation; essentially we have to have an awareness about the power relationships that exist.’

Who to write to

Seasoned fundraisers, like Harvey McKinnon, recommend that writers address their letters to a specific recipient. Harvey points out that, ‘Most direct mail donors are female and in their sixties. Some writers address their letters to their mother, for others it’s a sister. If you always write for the typical donor your letter may work, it might make money for the charity. But’, he says, ‘don’t forget there are lots of people who do not fit a “typical donor” profile and it’s always good to be able to vary your style. If you are writing seven letters per year to your donor base, it is probably well worth targeting one or two of those letters to a slightly different audience. Perhaps younger and occasionally a male. I don’t plan this strategically when I write, but I don’t always have that 65-year-old aunt of mine in mind when I write.’

Harvey felt that Carlie’s story was so powerful he could write the letter without having anyone specific in mind. ‘I wrote this letter very quickly, to capture the emotion I felt when I was interviewing Carlie’s dad. As soon as I hung up the telephone I wrote the letter and then let it sit for a day. The letter really wrote itself – I just tweaked it. I believe, whether you are male or female, in your thirties, forties, or sixties and not the “typical” direct mail donor, when you read this letter the story can evoke a response.’

Harvey continues, ‘Most recipients of direct mail letters are parents. If they are not parents, they likely have nieces or nephews, or have friends who have children they know and love. For the most part, people like children, especially young children, and we know that alone has an impact on a reader.’

Getting the reader’s attention

Harvey makes the assumption that most people live their daily lives without waiting for this or any letter to arrive in their letterbox. ‘For the Make-A-Wish Foundation prospect package I made the assumption that most people in Canada had heard of the Foundation, as this is one of the top 50 charities in the country. I assumed, as well, that most people would have a positive attitude about the goals of the Foundation and be curious enough to want to open the envelope. My gut instinct told me that if they read the letter there was a fairly good chance they would respond to it.

‘Nevertheless, in making the assumption they have opened the envelope and are reading the letter, I also assume they still pay little attention to what they are reading. Most people tend to scan letters, so, I decided to use a large typeface and really short sentences and paragraphs to make the letter easier to read. If you read the first sentence, it’s not hard to go to the second sentence and the next. My theory is that short sentences and short paragraphs will keep you reading.’

Connecting with the reader

View original image

View original image

‘Now you have her attention,’ Harvey emphasises, ‘it is very important to connect with the reader. The best way to connect is to use of the word “you”, as often as possible. Every “you” is deliberate, from the beginning until the end of the letter. Usually, after I have written the first draft, I review the letter to eliminate “we” or “our” as much as possible. Then I add “yous”. It is difficult, sometimes, because of what is being said, to use a “you”, so I will use another approach to connect with the reader. I will write “I don’t know if you can imagine”, or “can you imagine?” I could say “you may not believe this”, or “as you may know” – all ways to try and involve the reader more in the story.’

The right length

‘Longer is better’ is a mantra of many commercial copywriters. In fundraising as well, many experts agree that longer is better when it comes to writing letters. Harvey says, ‘When it comes to prospecting letters, a four-page letter tends to be the norm.’

Harvey has two ways of approaching his letter-writing. ‘Sometimes I know the letter can’t be more than two-pages for budgetary reasons but, initially, I just write the letter, incorporating the material I think needs to be included. Then I see how long it is. Carlie’s letter ended up to be three pages. We made the decision to increase the size of the typeface and spread the copy out over four pages to make it easier to read. We could have made the letter shorter by eliminating some of the facts, but, in reality, an extra sheet in a package is going to add, at most, five per cent extra cost. Most of the costs are found in the labour of the creative and in the postage so, in effect, by doubling the amount of space you have to tell your story, and telling it well, the five per cent extra is well worth it.’

Writing the outer envelope

View original image

View original image

Harvey often debates whether using taglines and/or images on the outer envelope makes a difference in getting the pack opened. ‘In the testing we have done, like almost everyone else, we have found that half the time it helps and the other half of the time it makes no difference whatsoever, or reduces the response. There are many different kinds of donors and envelope teaser messages may not appeal to any, or all of them.’

Harvey ‘wrote’ the Carlie pack’s envelope last, as he usually does. ‘There may be the odd time I think of the envelope first, sometimes I get an image but, most of the time, I write the letters first,’ he says. ‘I write the letter and something emerges from that which is perfect for the response form, which leads to the development of the envelope.’

The letter

View original image

View original image

There is absolutely nothing worse than watching your three-year-old child dying.

‘This is a terrifying opening sentence,’ Harvey says. ‘The leads, the opening lines of the letter, are absolutely crucial. Lead-ins are always important. When you pick up a novel, for example a mystery (or even a non-fiction book on fundraising), you read the first sentence. If it doesn’t grab your attention, you put the book down. I know it is the same when people read newspapers, or magazines. People tend to scan and if something attracts their attention, they will read further.

‘I try to write powerful leads. I like really short sentences. I think visually, and research seems to support this, this makes it much easier for people to read. If people read a few paragraphs that are each a new sentence, each one line, I think they are more likely to continue reading, if the copy is well-written.’

In addition, Harvey says, ‘We are being deliberately specific here when we say “three-year-old” – this adds credibility and impact. And we deliberately chose the word “child” rather than “daughter” – to be more inclusive of all parents, parents who may have sons as well as, or instead of, daughters.

And there is nothing better than stealing her back from heaven.

‘I made the conscious decision to “give away” the punch line in the second paragraph,’ says Harvey. ‘Perhaps keeping the outcome until later in the letter might have been more strategic, but I felt it would have been unkind not to reveal early on that Carlie survived. I believe the way we revealed this fact, perhaps, makes it even more likely the reader would keep on reading.’

Harvey adds, ‘Those are the exact words Carlie’s dad used when speaking to me. Normally, I would not use religiously charged words like heaven, but I believe that even people who are not particularly religious (and I have no idea whether her dad is religious) would think heaven is appropriate.’

My daughter Carlie came back from certain death thanks to people like you.

‘Another one sentence paragraph,’ Harvey stresses, ‘you create the possibility that the donor, too, can effectively bring a child back from certain death. Note also the use of assumptive, inclusive language, “people like you”. Who wouldn’t want to be included in a group that could do something as wonderful as saving a child’s life?’ asks Harvey.

I hope you will give me a moment of your time because I am not a fundraiser, I am a parent.

Harvey states, ‘You are asking for the reader’s time, as a parent, making the assumption that the reader may also be a parent, or grandparent who has an interest in children. And you are also creating a sense of “them” (fundraisers) and “us” parents and grandparents, including the reader once again.’

And when I tell you my story, I think you will realise that you can make miracles happen...

‘This is a pretty powerful suggestion – that one can learn how to make miracles happen,’ Harvey adds. ‘You are asking the reader to think about how she might feel about something that could happen, in the future. Note once again the use of assumptive language – the letter assumes the reader is going to listen/read the full story.’ Harvey adds, ‘It’s also stimulating her curiosity and the use of the ellipsis encourages the reader to keep reading.’

My daughter Carlie was a perfectly healthy child. Then one day she got a bad fever.

‘This sentence,’ Harvey points out, ‘emphasises that this situation could happen to anyone with a perfectly healthy child. The story has been pared down to the essentials. We are not told any more information than is necessary. We have cut straight to the tragedy.’

We took her to the hospital only to discover every parent’s nightmare. Carlie had cancer.

Harvey says, ‘I broke this tragic information down into two sentences. This creates a sense of anticipation – what did the parents discover? I wanted the cancer to stand out. For a parent, this is terrifying news. By using the phrase “every parent’s nightmare” you connect once again with the reader, making the assumption she is a parent, or a grandparent.’

We started the treatment and we prayed.

Harvey states, ‘This is a clear, concise statement. It keeps the story moving, as simply as possible. No need to describe the treatment – it’s unnecessary. ‘Using the word prayer alludes to the religious aspect again – in reality, even non-religious people are likely to pray in a situation like this.’

Her grandmother gave her a wonderful surprise.

‘This is a kind of relief, the story becomes more positive and helps to generate a sense of curiosity; and that sentence continues over to the next page. I always try to have a continuation to the next page to encourage people to continue reading. One should never have a full stop as the last thing people see because it’s too easy to stop. You’ll note newspapers and magazines do exactly the same thing.’

But three weeks before Carlie got her dream wish (she wished to go to Sea World), she came down with pneumonia and influenza. Six days later Carlie was in a coma.

‘This is so sad,’ says Harvey, ‘and is the most crucial part of the letter. With these kind of letters the story usually goes up and down emotionally, generating positive and negative emotions. When the tone goes down emotionally, you expect that it’s going to be coming back up. We tend to expect that we are going to see something positive after something negative has happened. We haven’t done that here. The tone goes down again and again and again. She gets an infection, goes into a coma. And then gets worse again.’

The doctors told her she had a 20 per cent chance to live. Then it got worse.

Harvey states, ‘Structurally, I think this is pretty powerful. Rather than saying “Carlie’s situation is getting worse, she had a 20 per cent chance to live”, I put this information into separate sentences, just like the “cancer”, just as we did with the next paragraph, “She was paralysed”. I love three- and four-word sentences. ‘

By Carlie’s seventeenth day she had lost 98 per cent of her lung capacity. She had 13 tubes in her tiny body. She was paralysed.

‘Instead of saying, “she lost most of her lung capacity”, I wrote: “she lost ninety-eight per cent..” When we say there were “13 tubes in her tiny body” it is far more powerful than being vague. Specificity adds power. I wanted to make the letter as visual as possible so the readers could literally “see” for themselves… her tiny body. You get a very clear visual image because she’s only an infant.’

The doctors told us she wouldn’t live through the weekend. I don’t know if you can imagine how horrible it was to hear this news.

‘This is one of the most dramatic moments in the letter. We invite the reader to reflect on how they would feel in a situation like this. The parents are told that their child won’t live through the weekend. This is terrifying. The doctors would have told all the staff as well. The nurses leave on Friday, knowing that this baby is going to be dying over the weekend. I’m sure they would be emotionally affected, like most people. And they were shocked to see Carlie’s dad still there Monday morning when they returned to work.

‘In effect, the “miracle” happened over the weekend.’

Just 12 days later…when Carlie returned two weeks later.

Harvey says, ‘Again I have pared down the story, skipping ahead two weeks. There was more material we could have included in the letter here, but I always try – sometimes I don’t succeed – to eliminate anything that doesn’t propel the story along. I think anyone who is a writer always makes decisions to leave out good information because it slows down a story. So we decided to go straight to the miracle two weeks later.’

Today, three years later, Carlie is a healthy and energetic child.

Harvey emphasises once again, ‘I want the reader to know, as a result of the generosity of donors, Carlie survived when she should not have survived. Why? Because of her desire to get her Make-A-Wish gift. And I believe this is true. There is no logical reason why she should have survived.’

I know we were lucky. Most of the kids won’t get the chance to live long lives. But they can get their most cherished wish fulfilled.

Harvey says ‘One of the most important goals in the writing was to make it very clear that many of the children who get a Make-A-Wish gift do not survive – you must be sensitive about that issue. So, I added a couple of paragraphs about this reality. Even if a child doesn’t live, you can still give her this precious gift before she passes on.’

Harvey reminds us, ‘This letter could easily be sent to people who have lost a child, or to friends of someone who has lost a child, or cousin, or whomever. I think personally and politically it’s important to be sensitive and I also think this moves the letter along.’

As you know, when you help kids through Make-A-Wish, you also help dozens of people who love that child…

Harvey states, ‘The reality is there are parents and grandparents and lots of people who love the child in the story who are also helped, just as Carlie’s dad was in this case.’

I am hoping today that you’ll join me and help other children who are very ill. Please send a gift to the Make-A-Wish Foundation today, so that a child’s dream wish can come true.

‘Now we have arrived at the actual ask. You have to ask for the money,’ Harvey stresses. ‘How often you may ask depends on the letter. Many times I ask on the first page of the letter. For instance, if it’s a “house” mail piece going to current donors, there’s a good chance it is only a two-page letter, in which case you need to give the reader the proposition immediately. But Carlie’s story has more emotion than many of the letters I write. I wanted people to take the journey, to be thrilled that this child lived and to explain that her parents really believed – and they dobelieve – that it was because of Make-A-Wish that she survived.

‘Make-A-Wish donors who did not know this child’s story made gifts hoping to help a child, and this is exactly what happened. The reader is invited to become one of these generous people. Later I ask them again to act while the letter is in their hands. It’s a directive telling them exactly what they need to do.’

You may even bring back a child from heaven.

‘This powerful last line refers to the beginning of the letter. For people over 60 years of age, who tend to be more religious, even mentioning the word heaven is probably, from a fundraising perspective, a good thing to do.’

The PS

Harvey says, ‘The focus of the PS here is to point out the “join our monthly giving club”, which is the best way for people to give to the charity. We know the PS is one of the most important parts of the letter and often the most read part of the letter. Generally speaking, when you mention monthly giving in a PS you get an increase in the number of monthly donors. Monthly donors are so valuable for most organisations that we do this frequently. In some cases, however, we may restate the case, or the story, because people generally tend to flip back and forth in these letters. I was hoping that – because of the way this letter was designed, with short sentences, big type and a strong lead, as well as the emotion of the story itself – this letter would be more likely to be read from top to bottom than most fundraising letters.’

The reply device

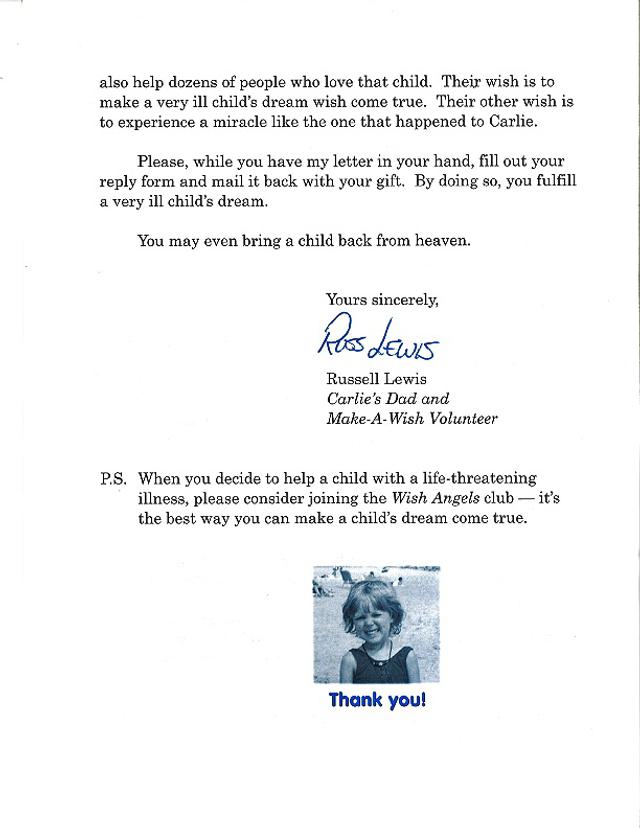

View original image

View original image

‘Last, and not least, the reply device,’ says Harvey. ‘This is a fairly standard reply device. There is, however, one twist: there is an option to donate a sum of $6,518. We put that figure in because it is the actual average cost of granting a wish. Every now and then, when I’ve done that before, you find a donor who is willing to donate at that level. We did this once for a hospital when the price point for a piece of equipment was $6,942.73. Thirteen people “bought” this device. These donors upgraded from an average of $65 to nearly $7,000. It never hurts to ask.’

© SOFII 2010